A Brief Ode to Data Minimization

Data is real, and it can hurt you.

Conversely, data cannot hurt you if you do not pluck it from the ether and rudely force it into existence in the first place.

Let's talk, briefly, about data minimization.

Data minimization is a term that describes what is, on the face of it, an extremely simple concept: data is inherently dangerous, and you should capture and store no more of it than the bare minimum that is required to accomplish your goal.

I like to think of this as the First Law of Data Minimization.

In official terms, such as those delineated in the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), data minimization is defined as the collection and storage of personal data in ways that are "adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which they are processed." Rather similar language appears in California's landmark 2018 California Consumer Privacy Act, defining how a "business’ collection, use, retention, and sharing of a consumer’s personal information shall be reasonably necessary and proportionate.."

Simple as this concept may appear, and despite the fact that it's a core legal principle in some jurisdictions, I've found that it's often an uphill battle to get people to really grasp why data minimization is important.

Partially, this is because we live in an era in which we've largely been conditioned to believe that more data - and more information in general - is always and inevitably a good thing. Our species has been collecting and digitalizing great gobs of the stuff at a constantly accelerating rate over the last 50 years, and this process shows no sign of stopping anytime soon.

Our culture, and by proxy most of the people living in it, has largely associated this incredible data gold rush with positive stuff like innovation, social process, and increasing global prosperity. Meanwhile, the downsides of this feverish process of data collection and archiving have largely received far less attention, despite the valiant and still very-much-ongoing efforts of data and privacy activists and ethicists.

To extend the analogy, most people think that libraries are good, and most people operate under the assumption that a bigger library is inherently better. They then transfer this understanding about the relative goodness of analog information onto the digital world.

i have so many of these

Which is a problem, because modern digital databases are not physical libraries that focus on physical and largely verified publications. They are far wilder, more heterogeneous, and potentially dangerous things than that.

By virtue of their immense size, networked nature, and global accessibility - by authorized or unauthorized means - our modern digital databases can far more easily be abused by bad actors, and abused at an immense scale, than the analog libraries or document-containing file cabinets of the past. In the wrong hands, these databases can be used to oppress the innocent, suppress free speech, violate privacy, and even target individuals for deadly attacks. What's more, the risk of abuse rises in tandem with the addition of more data to the system.

Many old myths and legends revolve around the theme of the terribly high price of knowledge. Sometimes, it's better to leave certain information twisting in the ether. Sometimes, the gauzy shapes forming in your wizard's orb are better left un-messed with. (And what better exemplifies modern tech culture attitudes than the fact that the blank-eyed ghouls who founded Palantir decided to completely ignore Tolkien's pointed messaging about how dangerous and madness-inducing palantirs are in practice?)

Let me turn to another analogy for data minimization.

Some people claim that data is the new oil. Others claim that data is the new toxic waste.

Personally, I think of data as a lot more like explosives.

Almost everyone agrees on the following points about explosives:

Explosives have a number of practical uses, and some explosives are considerably more sensitive and dangerous than others. People who work with explosives should have to undergo some form of special training, and should have to follow clearly-defined laws and rules about collecting, storing, and using them.

The person storing the explosives is responsible for keeping track of who has access to them, and why. Finally, storing too many explosives in the same location is dangerous, and ideally, you should only keep around as many explosives as are absolutely required to achieve your goal.

Most people still find "explosives are dangerous and should be treated with great respect, and you should try to hang onto as few of them as possible" to be a lot more intuitive than "data is dangerous and should be treated with great respect." But hey, good news: this popular perception does seem to be changing rather rapidly!

The bad news is that this is because of DOGE.

Elon Musk's loathsome assault on the federal government in the form of DOGE - his squad of trust fund, slavishly Chat-GPT dependent rat boys - has been a total disaster, a senseless evisceration of the institutions that actually did make America great.

But DOGE's ongoing vandalism has, totally unintentionally, done one good thing. It's provided those of us who spent the last 15 years desperately trying to convince other people that data can be dangerous with an incredible assortment of cautionary tales - and they're creating more of them every day.

DOGE's boat-shoe wearing little vermin are engaged in two primary dangerous data activities, both of which are directly relevant to data minimization.

First, they're trying to create new mechanisms for collecting data that can be used to accomplish shitty authoritarian ends. Second, they're taking advantage of and consolidating data that was already collected by prior, pre-DOGE government programs - many of which were begun with the best of intentions. This process has been described in detail in a huge number of recent, raw-terror inducing news stories.

Which brings me to another core, cruel truth about data. It doesn't give a shit about your original intentions. Your data collection program may be operating with intentions purer than the driven snow, with a degree of moral purity that could stun a biblically-correct angel from 50 yards away.

All of this can be true, and yet, simply because your data exists, that means it can be exploited by a sufficiently motivated bad actor. Call this the Second Law of Data Minimization.

Yes, you can try to reduce the risk of your data being exploited by bad actors by various means, like proper security and routine deletions. You can think carefully about what you're collecting, and why.

But once you've created the data, that risk is always there. In modern digital systems, even deleting the data doesn't eliminate the risk entirely. You wrested that data from the eternal void, and, comrade, you're now responsible for it.

The only way to truly ensure that your data remains secure is not to collect it at all. In other words, data minimization. In other words, sometimes you need to leave those aforementioned eldritch shades muttering incantations inside the orb.

To take this back to the current DOGE debacle, we know that their team is taking merry, gremlin-style advantage of breaking into government databases that were largely constructed by ethical, upstanding people who never wanted their data to be used for evil purposes. Unfortunately, the fact that the people who collected all that data were largely good and well-meaning ultimately seems to have mattered less for the final outcome than a mouse fart in a hurricane. That data existed, and the wheel of fate dictated that a pack of broccoli-haired fascists in boat shoes were granted access to it by the dual forces of Elon Musk and the American voter.

This is the third law of data minimization: you will never be able to fully predict how your data might be used for unexpected and evil ends. The future is unknown to us, and even our best efforts at red teaming and risk assessment will inevitably fall short. I do not think many people who work for the federal government anticipated that Elon Musk and an assortment of snot-nosed fetuses would suddenly kick down their doors.

This is not a dig at them (and God knows those poor federal workers have already suffered enough in recent months).

Not many people, for one reason or another, thought that the MAGAs actually intended to so quickly and outrageously carry out the Dipshit Blitzkreig that was enunciated in Project 2025.

But they did, and they are. And now they've got all of our data.

Let's turn to American history for another example of how well-meaning data collection can so easily be turned to unintended and unanticipated ends.

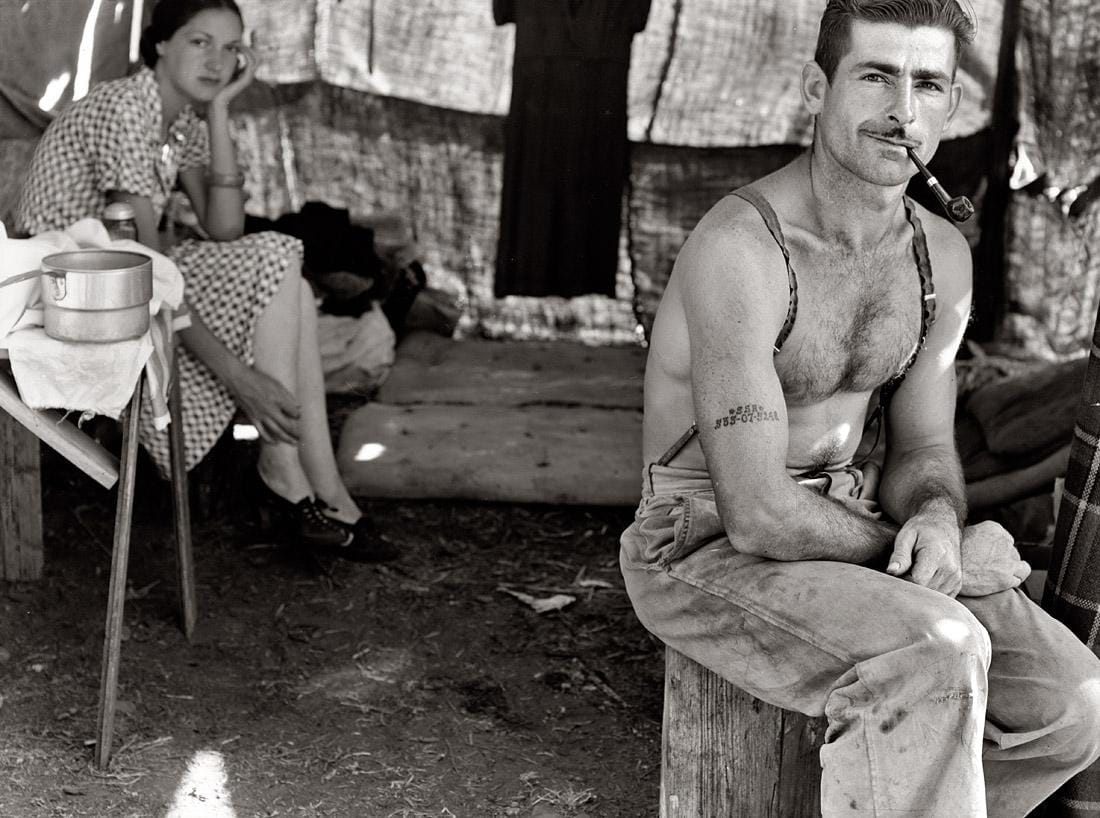

I'm reading Sarah Igbo's excellent "The Known Citizen" right now, which includes a fascinating look at the privacy concerns that swirled around the introduction of the Social Security program during the 1930s.

For a while, the Social Security program administrators rejected efforts from other government agencies and from outside entities to access the data. They were concerned, correctly, that giving into these requests would erode public trust. And after a considerable amount of initial apprehension (and a lot of caterwauling and complaint from New Deal-loathing conservatives), the public largely did trust the Social Security program, and the secure nature of the numbers that they'd been assigned.

people used to get their social security numbers tattooed on their flesh! it was wild!

Mind-blowing as it might seem to us in our identity-theft bedeviled age, 1930s Americans casually published their SSNs in the newspaper (or published the SSNs of people they were trying to track down), purchased jewelry engraved with their nine-digit identities, and even, on occasion, had their social security numbers tattooed onto their bodies.

But then World War II and the draft came, with its attendant war-time demands for better information on what American citizens were up to, the Social Security Board grudgingly began to give in to more government requests for access. It seemed like the patriotic thing to do.

While the Board claimed during WWII that it would stop accommodating such national-security related requests once the unpleasantness had subsided, this isn't how it shook out (as you've probably guessed). The Korean War gave way to the Cold War, and J. Edgar Hoover himself soon began breathing down the Social Security Board's neck, demanding information that he ominously claimed could be used to fight "international communism."

Other requests for Social Security data access also began to stream in, related to everything from public health to tax evasion to settling the accounts of the dead and mentally ill.

And although the Board was still deeply uncomfortable with the situation, they continued to give in to more and more of these requests. As Igbo puts it, "... the web of data that had been spun out of an initial thread—the decision to assign nine-digit-identifying numbers to workers in 1936—was too valuable and alluring for other interest parties to resist."

In other words, pure and simple as the intentions of the creators of the Social Security Program may have been, the mere existence of a vast and unprecedented repository of data on the American people inevitably and almost immediately attracted a bunch of people who wanted to use it for a dizzying array of other, often ethically fraught, purposes.

Fast forward through history, and we find ourselves considering the Supreme Court's insane decision on June 9th, 2025 to grant the sniveling fetuses of DOGE access to that same repository of Social Security Administration data on millions of Americans that J. Edgar Hoover found so intriguing back in 1958.

A rotting zebra carcass on the African savanna will inevitably attract jackals and vultures. An unsecured dumpster filled with garbage will unerringly result in raccoons. And so too will the mere existence of a large stockpile of personally identifiable data attract the attention of both violence-minded feds and evil South African venture capitalists.

This is not to say that the Social Security Program, and the process of data collection that's required to make it work, was a mistake. The Social Security Program was, and still is, one of the finest ideas that America has ever had, and I hope everyone who seeks to destroy it has their genitals bitten by fire ants.

Which brings me to the Fourth Law of Data Minimization: it doesn't mean "no one should collect data ever."

Data is very useful, and there are a lot of very good reasons to collect different types of data of varying levels of sensitivity - like, say, for the Social Security Administration, or for the Census, or for socially-beneficial academic research.

The main takeaway here is that if you're starting up a data collection program, you're under a serious moral obligation to think about the risks that collecting and storing that data might entail in advance.

Once again: you dragged that stuff out of nothingness and gave it coherent form, and that means you're in charge of it. For good or for ill.

And while the founders of the Social Security Administration way back in the Great Depression can be somewhat forgiven for not seeing the Cold War, the Internet, and Elon Musk coming, you and I have no such excuse in 2025.

There are a number of ways to go about exercising the serious moral obligation of data minimization in practice. In my opinion, the most fun way to do this is role-playing as if you are an incredibly evil person who would like to do incredibly evil things with your data. By which nefarious means would they get access to it? What freaky shit would they do with it if they did get that access?

You can use this threat modeling exercise to help you get a sense of how useful your data might be to bad actors, and which portions of your data are more sensitive than others. From there, you can start thinking about minimization (among other salient concerns).

Do you really need to ask that particular question - or, in other words, do the risks of collecting that information outweigh the benefits?

Do you really need to keep this data for perpetuity, or will you be able to get what you need out of it if you keep it for just six months?

Whenever you're thinking of collecting data, you should, unpleasant as it is, remind yourself about DOGE.

You should think about what a cadre of naked mole-rats with crypto investments might do with your data if they were able to get their paws on it somehow, even if the possibility of this actually happening seems impossibly remote.

Because you never know.

Further Reading on Data Minimization

Many people have written useful things about data minimization. Here is some additional reading on the subject that I can recommend:

The European Data Protection Supervisor definition of data minimization - which is enshrined in European law, both in Article 5(1)(c) of the GDPR and Article 4(1)(c) of Regulation (EU) 2018/1725. So you know, don't just take it from me.

The UK Information Commissioner's Office has a nice explainer of data minimization and how it exists under the UK GDPR.

The ICRC Handbook on Data Protection in Humanitarian Action, which frequently cites the importance of data minimization.

An interesting take on data minimization as a tool for AI accountability from the AI Now Institute.

AccessNow's Estelle Massé on the importance of data minimization for safe data transfers....and AccessNow's 2021 report on the importance of data minimization safeguards.

EPIC's explanation of data minimization, with references to relevant laws in California and Maryland.

Troy Hunt on data breaches and data minimization, emphatically making the case that you cannot lose data you don't have.

A new white paper from the Future of Privacy Forum that looks at the current trend towards "substantive" data minimization rules - IE, rules that will hopefully be more effective in practice than the older "procedural" data minimization paradigm (which all-too-optimistically relied upon data collectors to do the right thing).

The OHCHR Berkeley Protocol on Digital Open Source Investigation contains a nice example of how the data minimization principle can be applied to open source investigations into human rights violations. In their words: "The principle of data minimization prescribes that digital information should only be collected and processed if it is: (a) justified for an articulable purpose; (b) necessary for achieving that purpose; and (c) proportional to the ability to fulfil that purpose." (p13).