Drones in the Ukraine War: April 12th to April 25 2022

Drones for witness, aid-washing, 3D models, and more

I'd managed to stick to a regular update schedule for these, and then…my partner and I both got Covid. After two solid years of avoiding it. We're fine. I've had nothing more than sniffles and some mild tiredness. My partner was pretty miserable for a weekend, but is also feeling much better. We're grateful we're vaccinated. And I also think it's no coincidence that it feels like most of the Covid-cautious people I know have been contracting it in the last 3 weeks, soon after remaining Covid-control measures across the US started to be lifted….

DRONES FOR WITNESS

In recently recaptured cities and towns, Ukraine is in the midst of a grim process of documenting potential war crimes committed by Russian troops.

In Bucha, drones appear to be already being used by international war crimes investigators, who have, per this WSJ story, used them to create a 3D map of the entire city. (More on that later in this post).

Journalists and private citizens also are using drone imagery to convey the scale of the violence. In this haunting drone video from Bucha, which appears to have been shared by the Kyiv Regional Military Administration, the pilot flies over a so-called “car cemetery.” This is the place where local authorities have placed vehicles that were found with their owners dead or injured inside.

Another video, likely shot by journalists with Reuters, uses a drone shot to convey the staggering scale of the newly-dug graves in the Kyiv suburb of Irpin.

Drones are also being used to document very early efforts at rebuilding. In the coastal town of Kozarovichi, Igor Lutsenko posted a video shot on April 10th, showing widespread destruction and the ruins of classy country houses. In the first shot, wreckage from a Tochka-U missile is visible lying on the road, next to some ordinary-looking residences. Here’s a shot of the same missile from the ground, as posted by @MotolkoHelp on Twitter.

In a later shot, two long low white buildings are visible near the water, next to a bridge crossing in the town.

The town of Kozarovichi has been the site of other now well-known drone videos from this war, including an infamous drone video of a direct hit on a Russian helicopter in flight. The later shots of this drone video, dated to March 4th, give us a clear sense of the regional terrain:

On April 14th, Kyiv Regional Military Administration leader Oleksiy Kuleba posted a drone video of restoration efforts on the bridge.

We are rebuilding the territory after the occupation by russian invaders.

— Oleksiy Kuleba (@KulebaOleksiy) 10:37 AM ∙ Apr 14, 2022

The bridge crossing began to work near Kozarovychi village. The bridge crossing was destroyed by warfare. It was partially restored. This will allow to get to the Ivankiv community faster.

Of course, the Russian side is also using drone imagery in similar ways. Consider this Telegram video posted by the People's Militia of the Donetsk People's Republic (DNR) on April 11th. The videographer uses drone shots to emphasize damage to a monastary in the village of Nikolskoe.

Another DNR video from April 13th uses drone footage to emphasize the movement of “humanitarian cargo” from Moscow into Donestk.

DRONES AND “AID-WASHING”

“Aid-washing” is a term from the humanitarian sector, referring to a practice where a company or organization, eager to brand itself as benign, partners with an aid group to enhance its own image. When we look at the recent rush of drone companies - especially US drone companies - into Ukraine since the war began in early February, the analogies aren’t too hard to spot.

I don’t believe that the companies delivering drones to Ukraine necessarily have bad or untoward motives.

But it is important to remember that these companies are very motivated indeed to portray their drones as maximally useful in the Ukrainian conflict zone. They’re very interested in knocking DJI off its pedestal as the #1 consumer drone brand (and the most visible consumer drone in Ukraine). They also want to associate their drones with the Ukrainians as “the good guys.” They’re not exactly neutral sources here.

This is why I’m maintaining a healthy sense of skepticism about recent stories and press releases coming out about how the drone kit donated to Ukrainian forces by aspiring DJI competitors is faring in the real world.

Far as I see it, it’s still rather early to declare that these drone products, often delivered to Ukraine in relatively small number, are making a decisive difference one way or another. We’ll have clear information on how well these new drones actually performed soon enough.

One data point from my own efforts to monitor drone use during the war: I have yet to make a positive ID of a US-made small drone in action on the battlefield in Ukraine. This doesn’t mean they’re not out there, of course. But it is an interesting indicator that footage of these drones in action doesn’t seem to be making it to the usual sources of OSINT data.

MAPPING THE WAR IN UKRAINE IN 3D

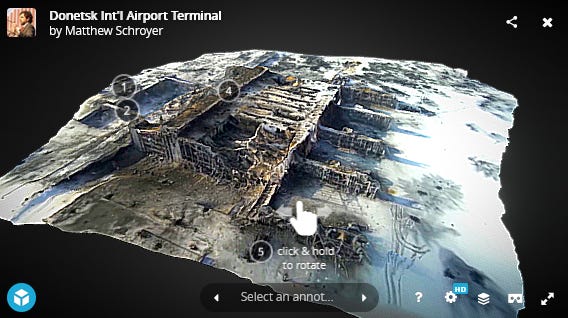

Back in 2014, when I was first getting interested in drones, I was mesmerized by this 3D map of the Donestk airport. Shot by a Ukrainian Army fundraising collective called Army SOS and produced by drone journalism expert Matthew Schroyer, it was one of the first examples I'd seen that used drone imagery, annotations, and photogrammetric tools to truly tell a story.

Around that same time, early drone journalism pioneers Dickens Olewe and Ben Kreimer of African SkyCAM used similar techniques to produce high-resolution 3D maps of the Dandora dump area in Nairobi, Kenya.

To me, navigating those 3D models in Autodesk felt like navigating a video game that happened to have been generated entirely from real life. And you could do it all from the sky. Incredible. I started dreaming of the possibilities of a new form of 3D-map storytelling, one that combined 3D drone maps with annotations and text.

As I write this, in 2022, 3D drone data is still somewhat…experimental. While we're getting better and better at collecting and processing it, finding mainstream applications for 3D drone imagery has taken a bit longer. (Infrastructure inspection and crime scene reconstruction both are leading the pack).

Journalism, too, is getting there. A recent Economist piece on the fascinating ancient city of Great Zimbabwe opens with an extensive 3D model of the site, which was created by the “Zamani Project of University of Cape Town using terrestrial laser-scanning, structure-from-motion photogrammetry and drone imagery.”

Around the 2022 Ukraine war, a few GIS and photogrammetry enthusiasts (mostly from Japan) have begun to use a combination of drone data, satellite imagery, 3D software and Cesium to create explorable 3D-models from drone videos captured during the war. You can view some of the satellite models here.

A 3D model of the Ilyich plant was created by photogrammetric processing of drone video taken at the site on April 18. The model will be published on GitHub.

— Taichi Furuhashi 🇺🇦 (@mapconcierge) 1:38 AM ∙ Apr 22, 2022

Source: © romanov_92

t.me/romanov_92/101…

They're then annotating these models to add context, just as I hoped journalists would start to do back in 2014.

Destroyed housing complex in #Mariupol, #Ukraine. On the south side (right side of the image), the wall has been destroyed and the base of the structure is broken and tilted.

— Hidenori Watanave, Ph.D. (@hwtnv) 10:24 AM ∙ Apr 21, 2022

Simeon Schmauß or @stim3on on Twitter has also been doing some great work, by using drone footage captured from videos with RealityCapture software. Here’s an example from Borodyanka.

While these models might not be quite as detailed or smooth as those that have been intentionally created by mapping drone pilots, they're still impressively immersive.