Dronewatching in the Ukraine War. Part 2: Drones Make You Look Cool As Hell

Small drones as the newest tough-guy status symbol in warfare (sort of).

Ramzan Kadyrov and his like-minded Kadyrovite forces live lives surrounded with masculine, musky symbolism. Ramzan Kadyrov’s promotional Telegram videos - and wow, there’s lots of them - feature recurring themes that include thundering stallions, weightlifting, totally-not-rigged UFC fights, cars that go vroom, and gigantic gun collections.

Nowadays, Kadyrov’s stunningly macho propaganda videos also include - and are often filmed by - small, consumer drones. As inexpensive mass-market drones have demonstrated their unquestionable value on the battlefield, so too, have drones started to become something of a wartime status symbol.

Small consumer drones began their transformation from a toy for nerds to a frightening weapon of war almost as soon as the first DJI Phantom hit the global market in early 2013. The ISIL terrorist group swiftly began using both DJI products and more rudimentary custom-built DIY drones for surveillance and targeting purposes: by 2016, ISIL had begun to experiment with using small, cheap drones for dropping explosives, launching a global scramble to figure out how best to counter them. Small drones as weapons also began to pop up in the Syrian Civil War, and (as I’ve already mentioned) began to be used by Ukrainian fighters when Russia carried out its first invasion in early 2014.

In these early days of small drone warfare, drones were (as I argued in this Foreign Policy piece) less effective as military weapons than they were for throughly scaring the shit out of international observers. The rise of bomb-dropping ISIS drones in 2016 launched gazillions of news stories, research initiatives, and social media screeds: it also spurred the creation of a now-enormous industry dedicated to the problem of detecting and dealing with small, weaponized drones. While ISIL and other terrorist groups largely lacked particularly-impressive technical chops or financial resources around drone making and modifying, the actual effectiveness of their drones mattered less than their potential.

Fast-forward to the War in Ukraine in 2022. Highly technically skilled Ukrainian drone pilots - who tended to have a lot more expertise than ISIS drone pilots could muster up - spent the years between 2014 and 2022 tirelessly refining their tactics and techniques, and they were ready to use what they’d learned on a larger scale than ever before when Putin launched his ill-fated invasion. Thanks to global-scale fundraising drives to support Ukraine, they also had funding. As of February 2022, small civilian drones have become more than effective propaganda tools: they’ve also become truly potent weapons for intelligence-gathering, targeting, and dropping small explosives on the modern battlefield.

But that doesn’t mean small drones aren’t still propaganda tools in the War in Ukraine. Of course they are. And this conflict is in the middle of developing a fascinating visual vernacular around their use.

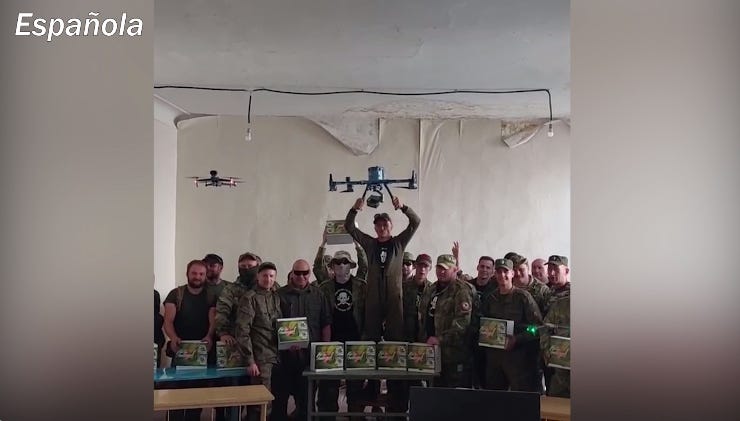

There’s a specific genre of social media video and photograph that I’ve come to recognize, adopted by both Ukrainian and Russian fighters in this conflict. Let us call it the Manly Drone Donation Thank You Note, intended to show public gratitude to the various civilians who have pooled their money together to buy civilian drones for the lads on the front-line.

Sometimes, a consumer drone hovers very close to the camera. Usually, the fighters are fully outfitted in battle garb, often wearing guns.

Fierce looking military men hold a drone, while others stand in the shot their arms folded, glaring into the camera. Sometimes, they all might say thank you together, unison. More often, the men just continue to look fierce, while an appointed person reads off some words of thanks.

The men are, I’m, sure, genuinely grateful. But there is another meaning here, and it is: “I hope you see this, enemy, so you know that I intend to use this drone’s electronic eye to accurately splatter you with a ATGM.”

Ukrainian drone-fighting force Aerorozvidka has been using drones to fight the Russians since 2014, and they have mastered the art of depicting the visual drama - and intimidation - of drone warfare. With excellent production values and professional video and photography skills, nobody gets across a rather grim message to the enemy, via the medium of little flying robots, quite like they do.

Kadyrovite commander Aslan "Tornado" Khizriev peers at drone footage (likely shot with a DJI drone), in an undisclosed location somewhere in Ukraine. Posted by Ramzan Kadyrov's Telegram account on 11/5/2022.

— Faine Greenwood (@faineg) 3:17 AM ∙ Nov 17, 2022

There is another genre of show-off drone video that the Russians, and the Kadyrovites, particularly like. I have named it The Important Man Looking at Drones Looking at Things, in a way rather reminescent of those PR photographs of Kim Jong-un staring at factories that the North Korean government likes to put on the Internet.

In these videos, a fresh-faced soldier who only looks like he’s 14 years old, probably, holds a consumer drone controller with a screen attached. He is showing the screen to a much older and senior commander, who often has a beard, is bristling with all manner of radios and weapons on his person, and is often named something like “Tornado.”

The commander gazes with cunning eyes upon the stuff on the screen, in a manner that is intended to convey that he has crucial, genius insights into what is going on. These videos are often paired with older-school cuts of the same commander looking knowingly at paper maps.

The implication: our commanders know everything that is going on, and they are in full control of the situation.

Also, look at how cool our drone is.

The type of drone matters too, of course. Soldiers from both Ukraine and Russia like to show it off whenever they acquire a new DJI Matrice RTK or the even newer DJI Matrice 30, $10K-plus drones designed primarily for high-end, civilian enterprise uses (like mapping and public safety). While the Matrice is a handy workhorse for tasks like carrying thermal sensors or dropping explosives, it also comes with a certain cachet around how much it costs. The smaller, easily-foldable DJI Mavic (both the older 2 and the newer 3) have become beloved and reliable workhorses, something of a gold-standard in modern combat drone technology - and people have also come up with a profusion of ways to hack them, and modify them to drop explovies.

Meanwhile, the harder-to-find Autel Evo II is another desirable alternative, free of much of the baggage that DJI - what with its involvement in the Aeroscope controversy, and numerous other issues related to the company’s relationship with the Chinese government - lacks. (Autel is also a Chinese company, but has attracted considerably less negative attention in the last few years).

All these examples prove one fascinating truth: we’re watching a visual vernacular around using small, cheap drones to intimidate people being hashed out in real-time.

Drones are, in one sense, a very new phenomenon on modern battlefields. But the use of scary unmanned aerial objects goes way further back in the history of battlefield intimidation than you might imagine.

Over 2000 years ago, someone in China invented the first unmanned aerial vehicle: the kite. We don’t know where the inspiration for the kite came from. Some sources claim it derived from arrows. Others say our ancient inventor got the idea from noticing how a farming-hat flies off one’s head in a stiff wind, or observing the movement of war-banners in the breeze.

Whatever their origins, kites have been associated with war from the beginning: our first unambiguous record of their existence dates back to 200 BC, when a certain General Han Hsin was encountering difficulties with storming a well-guarded palace. The general seized upon the remarkably clever idea of flying a kite over the palace, in such a way that he might be able to judge the distance between his army and the palace walls: by this means, he’d be able to determine how long a tunnel he needed to dig to get in.

Kites quickly became a standard part of Chinese military operations, used for signalling, to frighten people and even, in 1232, as a mechanism for carrying out the first propaganda leaflet raid in history at the Siege of Kaifeng:

“The besieged sent up paper kites with writing on them, and when these came over the northern (i.e. the Mongol) lines, the strings were cut (so that they fell among) the Chin prisoners (there). (The messages) incited them (to revolt and escape). People who saw this said: ‘Only a few days ago the Chin (commanders) were using red paper lanterns (for signalling) and now they are making use of paper kites. If the generals think they can defeat the enemy by such methods they will find it very difficult.” - Needham, Joseph, Science and Civilization in China, Vol. 4, Pt.2, Cambridge, 1965, pp.568-602.

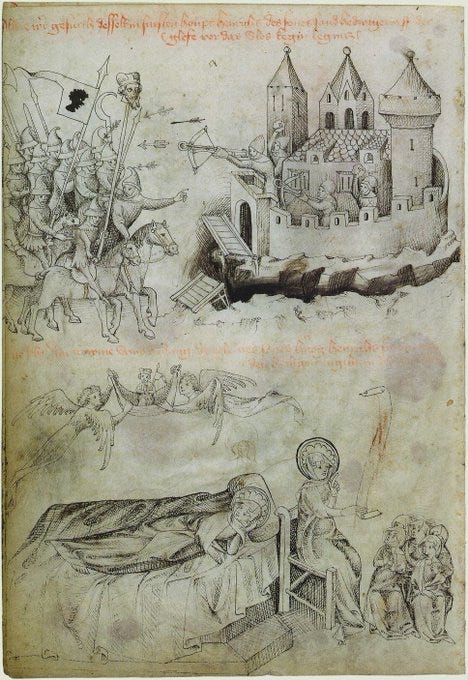

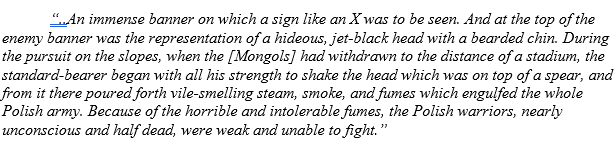

Just a few years after this, the Mongols dished out a kite-based war trick themselves.As they marched into battle against the Polish at the 1241 Battle of Legnica, the Mongols showed up with a truly frightening kite-like banner, which spewed some sort of loathsome substance (the below translated from Jan Długosz’s Latin by Clive Hart):

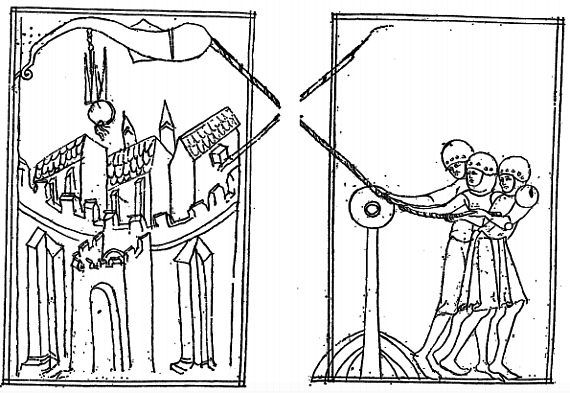

Kites may have been used to drop explosives in the Middle Ages as well. Walter De Milemete’s 1327 De Nobilitatibus, Sapientiis, et Prudentiis Regum, an instructonal manual produced for the young King Edward the 3rd, included illustrations of a curiously fish-like kite, which may have been used to drop flaming materials on soldiers below, an idea he probably got from the Mongols. A team from the History Channel even managed to recreate the design in 2008.

Not long after, around 1360, two Chinese Ming Dynasty military strategists published the delightfully named Huolongjing, or “Fire Dragon Manual,” intended to serve as a guide to the offensive uses of gunpowder. The book included an entry dedicated to a “divine fire flying crow,” a sort of bird-shaped aerial bomb that would doubtless have proved distinctly disturbing to the poor saps on the ground.

Small drones are, then, not just good to fight with: they’re also good to freak people out with.

They are also very good at adding to the historical record.

Next week, I’ll write about how small drones in the Ukraine War are bearing witness to war crimes.