Dronewatching in the Ukraine War. Part 3. An Aerial View of War's Horrors.

Drones can see what some might wise to hide. How drones may help war crimes investigators in the future.

A drone can see what some might wish to hide.

Humanity has looked down upon war, violence, and horror from the sky for as long as we have been flying. Small, inexpensive drones are part of a tradition that started over 239 years ago, not long after the first hot air balloon capable of carrying a person (or, in that first case, a sheep, a duck, and a rooster) was demonstrated by France’s Montgolfier brothers in 1783.

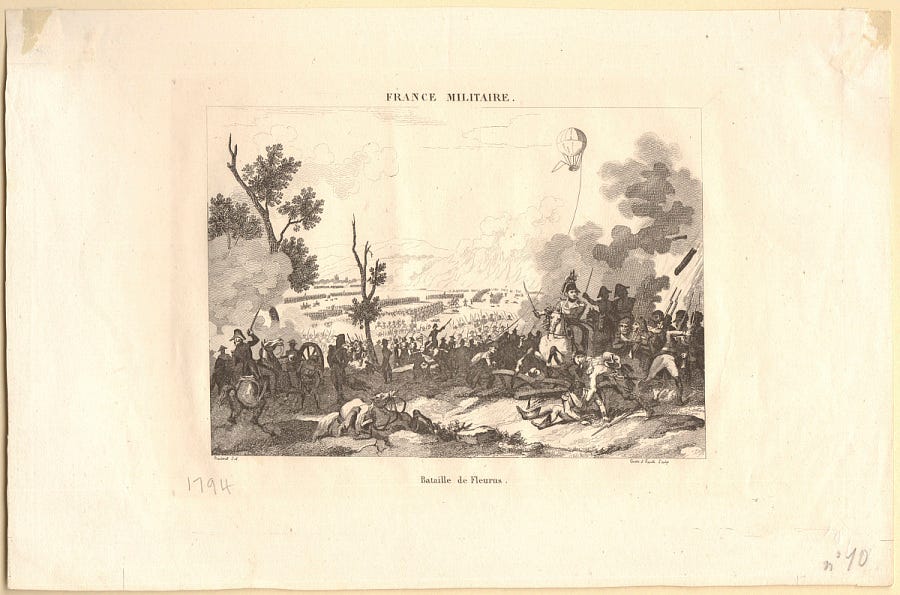

Aerial surveillance in warfare dates back almost as far as the invention of the hot air balloon in 1783. At the Battle of Fleurus in 1794 during the War of the First Coalition, French forces put a tethered observation balloon manned by spotters with telescopes up in the air, using a cable for two-way communication: the uncanny sight terrified the Austrians, who angrily argued that its use violated the laws of war. By 1862, both Union and Confederate fighters in the US Civil War had adopted hot-air balloons for spotting troop movements from as far as seven miles away.

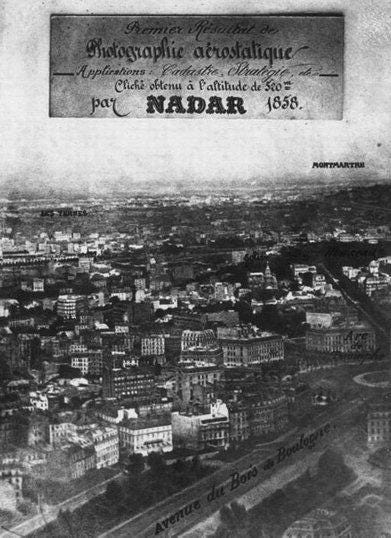

For over 164 years, we have been taking photographs from an elevated perspective, well above the chaos and violence of the battlefield. The flamboyant French balloonist and photographer Nadar took what are likely the first aerial photographs back in 1858 - ghostly black and white images that seem almost unreal in their antiquity, shot 45 years before the Wright Brothers first successfully creaked into the air in North Carolina. (Nadar would later establish one of history’s first airmail services during the Siege of Paris between 1870 and 1871, passing information right over the enraged noses of the Prussians).

Aerial photography first became a true fixture in warfare after the breakout of World War I in 1914, as both Allied and German forces swiftly figured out ways to use imagery from the air for both quotidian tactical purposes and to vividly, viscerally illustrate the horrors of war.

From this era, we have aerial images documenting the grim patterns of trenches on French battlefields, and even a view from above of the clouds of smoke kicked off by brutal gas weapons, used by the British in advance of the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

These images are old, and yet, they are remarkably similar to the aerial images captured by drones in Ukraine. Through the eye of an aerial camera, we clearly see tired and muddy men crouched in a European trench in 1916: in 2022, we’re seeing men huddled in trenches once again from a camera hovering many hundreds of feet above the violence, albeit in far higher resolution.

Aerial imagery was also used during this early photographic to document the human costs of war, beyond immediate battlefield clashes. Famously death-defying Australian photographer Frank Hurley captured some of the first aerial shots of the total devastation of modern warfare in 1917 from an airplane, in photographs that conveyed the sheer scale of the destruction in the Belgian city of Ypres.

Hurley clearly saw his role as one focused on storytelling about the loathsome nature of war - and his use of ground-based, composite photos to achieve those means embroiled him in a number of fascinating philosophical controversies about the nature of truth in photography.

Hurley’s grim aerial photographs of an immense landscape of burned-out buildings have, tragically, been replicated many times over by other photographers in other, modern, wars, all around the world. Drone photographers in Ukraine in 2022, following in Hurley’s footsteps, are simply using a slightly different tool to capture their own bleak photographs of burned-out buildings and mass devastation. The aerial view remains one of the best means of conveying the sheer scale of the destruction of modern warfare to global audiences far away from the fighting.

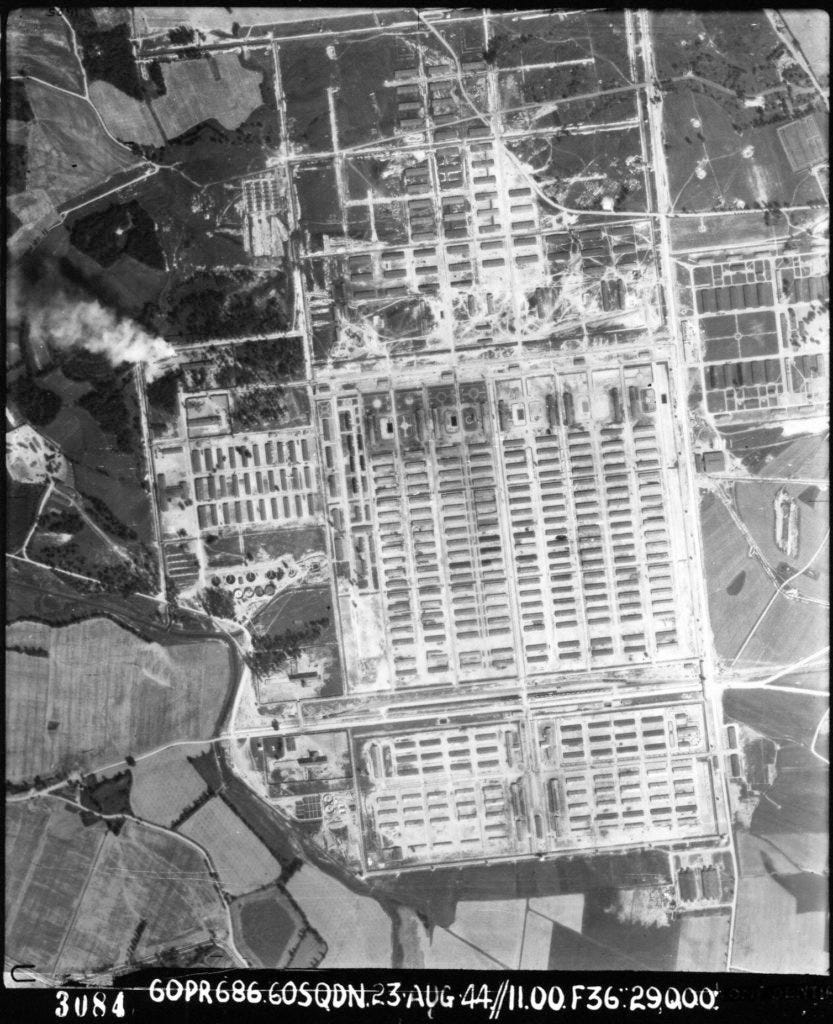

Aerial imagery has also long been used for the more specific purpose of collecting information on war crimes, or crimes against humanity. During World War II, allied spy planes on reconnaissance missions took aerial photographs of Nazi death camps on multiple occasions.

The Allied military analysts who reviewed the aerial photos and assembled them into orthomosaics did not realize the hideous nature of the work camps that their aircraft had sighted from the sky: they were laser-focused on finding targets to hit, not on spotting crimes against humanity from the air. (Indeed, was the possibility of doing such a thing even widely imagined, or known, at the time?).

In 1978, CIA researchers combing through these archival images would realize the true nature of what these images depicted, and the crucial evidence of Nazi crimes that they contained - including, horrifically, a view from above of a smoke plume created by many burning bodies on a pyre at Auschwitz.

The rise of truly high-resolution satellite imagery in the late 20th century brought another revolution to the practice of documenting conflict and war crimes from above. In July 1995, US military satellites photographed what appeared to be mass grave sites in eastern Bosnia, prompting an official UN investigation into the Srebrenica massacre in which over 8,000 Bosnian Muslims were murdered over a nightmarish two week period. War crimes investigators are still using aerial imagery - from satellites, and now even from drones equipped with LiDAR sensors - to find yet more of these Bosnian mass graves today.

As one example of the now-extensive use of satellite imagery in war crimes investigations, my old employers at the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative led the Satellite Sentinel program, one of the first major civilian efforts to monitor conflict with satellite imagery in the early 2010s, analyzing imagery collected by Maxar (now DigitalGlobe) over Sudan during the bloody conflict there.

Today, satellite imagery is playing a key part in documenting alleged violations of international law and war in Ukraine - and some of my former colleagues, now at Yale’s Humanitarian Research Lab, are working with the U.S. State Department to combine high-resolution satellite photographs and open-source data, producing quality evidence for investigators.

What then, do the small drones of today bring to the table, when other methods for documenting conflict and collecting evidence of potential war crimes already exist, and have for generations?

Drones are important because they have made it far easier, cheaper, and more accessible to document war, conflict, and the scale of human suffering from above. Since the modern consumer drone revolution really began in the early 2010s, people have used drones to photograph refugee camps, police violence, environmental destruction, grinding societal inequality, and much, much more.

In the last decade, drones have also become a more common tool for conflict monitoring missions - including in Ukraine. In the period between Russia’s first invasion in 2014 and the 2022 invasion, the OSCE Monitoring Mission regularly used small drones, including inexpensive consumer models made by DJI, to monitor the Donbas border region. They were still, it seems, flying up until the day that Russia’s tanks rolled across the border.

Since the war in Ukraine began on February 23rd 2022, and I began collecting as much drone-collected data as I could find for my database, I have seen many drone videos and photographs that may depict possible war crimes and human rights violations, as well as the investigative process of uncovering those crimes. My sample size is not scientific (and indeed, there’s no way it could): I simply draw from things I find on Telegram, Twitter, and other social media outlets, with the goal in mind of cataloging some small part of the torrent of drone-collected data that has emerged from this war.

Since the war began, pilots using inexpensive, consumer drones have watched overhead as a cyclist in Bucha was shot at by a tank, and captured footage of the bodies of Bucha’s dead lying in the street during the Russian occupation - directly contradicting Russia’s claims that the civilian deaths were somehow faked.

These drone pilots took great risks to get their aircraft in the air during the active occupation, knowing that it was possible that the Russians could use counter-drone technologies, like DJI’s Aeroscope, to find their location on the ground.

After the Russians departed Bucha in early April, journalists watched with drones as workers dug up hastily-buried bodies, shot aerial footage of devastated apartment buildings and playgrounds, and flew over the burned-out hulks of Russian tanks, trucks, and civilian vehicles, all jumbled together in a ghostly graveyard for machines.

War crimes investigators deployed to Bucha quickly began using small drones to create highly detailed photographic maps of the city, spatial data that will hopefully prove valuable to the detailed investigations that will unfold in the months and years to come. that In nearby Irpin, another site of horrifying violence during the early days of the Russian invasion, journalists used drones to document the staggering number of newly-dug graves in the sandy Ukrainian ground.

The drone data I’m collecting in my database is just one small part of a much greater corpus of data - scattered across a dizzying array of places on the Internet - that researchers will likely still be combing through many years into the future.

The relative newness of drone-collected data in conflict, and the sheer volume at which it is flowing out of Ukraine, presents considerable new challenges for the organizations that collect and catalog evidence of human rights abuses and war crimes. They are still in the process of figuring out how to incorporate drone-collected open source data into their existing workflows and legal evidence chains.

Here is one specific example of how a person flying a drone - and I use that frame deliberately, to avoid the pitfall of assigning agency to the drone itself, as if a human pilot isn’t flying it, looking through its single gimbal-mounted eye - witnessed what may be a potential war crime.

A Ukrainian volunteer drone pilot, tasked with observing Russian positions with his DJI Mavic 3 on a highway outside of Kyiv, was hovering in the air near a shuttered gas station when he saw a small column of civilian cars drive by, apparently unaware of the presence of a Russian tank lurking in the forest by the side of the road. The drivers draw close enough to spot the tank, and wheel to turn around.

One driver, in a white car, suddenly pulls over into the gas station driveway - his vehicle hit (as we now know) by gunfire. The driver exists the vehicle and raises his hands.

Almost immediately, he is shot dead by someone off screen.

Russian soldiers, wearing dark clothing, quickly emerge and surround the car, ushering away the man’s six-year-old child and an older friend of the family. They were permitted to walk to safety, and were picked up by the friend’s husband.

The murdered man’s name was Maksim Iovenko, he was a 31 year old who worked for a travel agency. His wife was killed in the incident, too. They had been trying to escape Kyiv to what they thought would be a safer location in the countryside, and the family had thought to put a handwritten sign in their car windows that said “Children.” Their bodies were left by the side of road, and the Russians, a while later, appear to have come back and burned them.

The investigation is ongoing. The drone video will, almost certainly, be part of it.