Dronnitsa, A Conference for Russian Battle Drone Pilots

In early September, Russia's small drone pilots held a new kind of get-together.

People who work with technology love to hold conferences. Russian small-drone combat pilots are, as it turns out, no exception.

The September 1st to 5th Dronnitsa event was first announced on August 1st. Organizers from the Coordinating Center for Assistance to Novorossia, or KCPN, claimed that it would bring together over 100 combat drone pilots, civilian drone experts, students, and wannabe pilots by the symbolically-laden shores of Ilmen Lake in the historic city of Veliky Novrogod.

Further support for the event would be provided by OPSB - a fundraising organization run by Russian mercenary, political strategist, and Ukrainian skull-wielding standup comedian Igor Mangushev (Bereg). The governor of Novrogod himself lent his support. So how did this thing go? I’ll try to provide some context, though the imperfect medium of Google-translated Telegram posts.

In a Telegram post, KCPN laid on the symbolism hard, noting that the “name of the meeting and the choice of location are directly related to Russian history and folklore. Sirin, Alkonost and Gamayun are magical birds of ancient legends and tales, which are mentioned in ancient chronicles.”

The symbolism didn’t end there, as even my badly Google-translated version makes clear:

“Novgorod is a place that can be considered the birthplace of the Russian dream of conquering the sky. From Novgorod in the 11th century St. John made his miraculous journey to Jerusalem, saddling a demon and turning home from the Holy Land in one night. Princes Prophetic Oleg, Vladimir the Red Sun and Yaroslav the Wise set off from Novgorod on their victorious campaigns against Kyiv. Gathering point - Rurik's Settlement. A new TRIP TO Kyiv is on the agenda!”

Over the course of the three day “rally,” pilots would compete in tests of skill, take master classes, hear about real combat experience, and network with one another. Beyond these immediate, somewhat summer-camp like activities, Dronnitsa had one overriding, main purpose: to signal to Russia’s leadership, and to the world, that small drones were a key part of modern combat. And to make it clear that much more support and funding from up top needed to be funneled in the direction of small drone pilots, as soon as possible.

Almost as soon as Russian tanks first rumbled over the border into Ukraine, Russian fighters have been lamenting their troops relative lack of expertise with small, cheap, commercial drones on the battlefield. While Ukrainians have been using both small DIY and commercial drones in the ongoing border conflict in the Donbass region since the first Russian invasion in 2014, better-resourced Russian troops largely didn’t see the need to bother with them, or the security issues that they brought with them.

That all changed as soon as it became apparent that Ukraine wouldn’t roll over in the immediate rout that Putin envisioned. Russian fighters noticed that Ukrainians were using small drones to spy on their movement, target artillery strikes on their heads, and to drop small explosives right into the hatches of their tanks while they tried to sleep at night. They wanted more cheap drones of their own. And they wanted to train more people to use them. To train the trainers, you might say.

1/ QUICK THREAD - a follow up to the earlier post about September "Dronnitsa" event that will bring together Russian, DNR/LNR drone pilots to Russia. Few months ago, there was a lack of drone on the front - now there is a lack of trained pilots because...

— Samuel Bendett (@SamBendett) 12:52 PM ∙ Aug 6, 2022

Dronnitsa would thus serve as the first step towards truly forming a Russian “instructor corps” of drone pilots, bringing together both fighters with combat experience and civilians interested in helping them out.

From my perspective, as a person who works in the (civilian) drone industry and who has organized quite a few (civilian) drone training conferences and workshops in my day, the most interesting thing about Dronnitsa’s organizing language is how normal it is. Workshops. Demonstrations. A drone pilot with experience, wearing a baseball hat, shows you what button does what. A free keychain or two.

Except, of course, the topic of focus for this event wasn’t map-making, or using drones for environmental research: it was the art of using commercial drones for war. And not just in theory, in the way you might talk about such a thing at a DC think tank. Dronnitsa might very well be the first conference ever held for practitioners of using small drones in warfare.

Dronnitsa’s lecture hall looked much like any other drone-conference lecture hall. Scratchy chairs. A camera guy. Lectures.

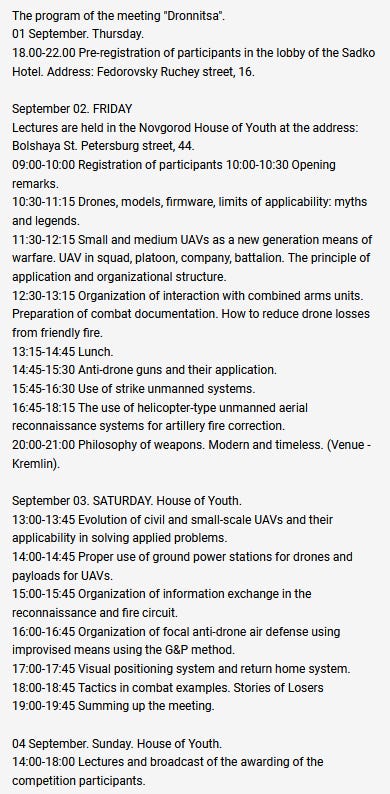

A full schedule, posted by KCPN, starts with the basic drone facts and winds its way towards the “philosophy of weapons” on the first day, and the second day hits more practicalities, from power (always a problem) to exchanging information between reconnaissance teams and firing lines.

KCPN’s official Telegram gives us an account of one of the competitive events - which sounds like a drone-based game of Capture the Flag, with the spicy addition of a EW-based anti drone gun or two:

“Five groups of operators of 6 people each moved around the training ground of several square kilometers of very difficult terrain, using their drones (2 in each group) to search for and destroy enemy equipment (it was designated by 5x4 m banners with images of the corresponding weapons and equipment) .

We tried to make the composition of the groups such that each group included both experienced operators, including those with combat experience, and beginners. The groups were supposed to detect the targets and transmit their coordinates to the headquarters. After that, the group had to find the target and remove it, informing the rest of the detachments about this by launching a rocket.

At the same time, the operators also tracked down each other and, if competitors were detected, they could transfer their coordinates to the headquarters, which meant covering the group with mortar fire (if, of course, the coordinates were transferred correctly). Points were awarded for the speed and accuracy of task execution.

The spice of the competition was added by the presence at the training ground of the DRG, armed with an anti-drone gun, which tracked down groups of operators and fired at the UAV.

Also, from time to time, an army jammer was involved in the case, the Headquarters monitored the situation at the training ground with the help of heavy VTOL drones The competition lasted from 13:00 to 17:00, after which the groups went to the evacuation zones. However, the last detachment returned to the camp already after dark.”

What was the outcome of Dronnitsa, and what did people learn from attending? As of late September, the conversation is still unfolding on the dozens and dozens of Telegram accounts I follow. But we can get a taste.

KCPN, the key organizer of the conference, posted a workmanlike rundown of findings on Telegram, which include:

“1. De facto quadcopters from DJI and Autel are accepted into service on both sides of the front, and this fact needs to be worked on. And KCPN will work.

2. There is a huge shortage of qualified UAV operators and an even more significant shortage of good instructors. KCPN has plans to train both.

3. A huge problem is the place of small UAVs in the organizational structure and their interaction with other units. And we will find a place for this issue in our curriculum.

4. The program of the meeting included training people and immediately a combat training task in a competitive form. This format has shown its effectiveness and will be further developed by us.

5. A unified center of competence is needed, capable of promptly responding to technical and organizational issues related to the use, assembly and repair of quadcopters. And KTSPN intends to become one!

6. A concept for the development and use of UAVs is required. We will think in this direction.”

Much of this will sound familiar to people who work in the civilian drone industry. The lack of qualified instructors. Confusion around where drones fit into existing organizational structures. The need for centralized standards, and agreed-upon experts. The purpose may differ, but the central challenge of wedging camera-carrying robots into pre-existing groups, run by humans, is not.

Russian right-wing think-tanker and spin-doctor Alexei Chadayev took a keen interest in Dronnitsa from the beginning, and he gave the closing speech at the event. According to Chadayev the Russian sky now contains, “instead of birds of paradise - Sirin, Alkonost and Gamayun - completely different birds now fly and sing songs of death: Maviks, Autels, Orlans and Bayraktars.”

And then he quotes some Hegel, from which he proceeds to noting that the Russian Revolution was “the crown of attempts to build their own Europe from shit and sticks, but on the solid foundations of the most advanced Western at that time - Marxist - philosophy.”

After bringing up Fukuyama, he gets here: “The subject of the dispute is not Crimea, but Rome. When we say "Crimea is ours", we mean "Our Rome" - not a city, but a synonym for civilization. If we can even just endure now, we will save something much more than just ourselves. But we must endure.”

It’s rather turgid, impenetrable stuff for a conference about drones. But it’s not really just about drones, of course.

On September 26th, just a few days ago, Chadayev returned to the Dronnitsa topic on Telegram:

“Next week I will go to a training camp in the near rear, where there will be a new study of the KCPN already with trainees of the instructor corps selected on Dronnitsa. I’ll take devices there from the training camp - not for instructors, but for fighters,” he writes.

Then, he adds:

“Recently - especially after the Dronnitsa - more and more tasks, if you like, of an engineering and technical nature have appeared. It's time to organize something like a laboratory, at least for the preparation of technical specifications and systematic communication with development teams. I myself will also go to learn a little, improve my skills in some specific areas of knowledge. At a military university. And then the general erudition is somehow already not enough))”

Next, here’s a Livejournal post by a long-time Ukrainian separatist and singer who attended the Dronnitsa event to observe and to provide entertainment:

“I will not comment on the military-technical part, although I listened with great interest to lectures on the theory and practice of the combat use of commercial drones, or rather, dual-purpose quadrocopters, which are sorely lacking in the Russian Army and in the NM LDNR. The KCPN, throughout its existence, has been trying to provide drones and not only to the militia of Donbass.

The militia gained combat experience in their use, and the KCPN developed into a powerful organization, which has already been involved in training the operation of UAVs for the personnel army. In 2014, this was unthinkable. This is the very civil society that the "liberals" have been talking about for so long. But, the society that they dream of, under rainbow flags and concentration camps for "quilted jackets" and "colorados", does not suit us. We have our own, with a Phoenix bird on the rally logo and stern men who left the front lines for several days to exchange experience.”

A prolific pro-Russian defense account on Telegram, Rusfleet, posted a series of four posts, summarizing a reader’s (who claims to be an artilleryman veteran of conflicts in Syria and in the Donbas) thoughts on Dronnitsa. As is inevitable in modern war, there are pictures of anime girls.

First, our correspondent notes that operating units “at all levels” must be “saturated” with “compact aerial reconnaissance, weapons, detection and countermeasures.”

While Russia’s military leaders have failed to provide front-line soldiers with cheap drones, volunteers and soldiers have stepped in to deal with the “catastrophic” drone shortage, using crowdfunded cash to purchase commercial drones, from DJI at the high-end (harder to get) vs whatever can be sourced from Aliexpress at the widely-reviled lower end.

He then outlines the process that Russian technologists must follow to provide drones to Russian soldiers via officially sanctioned channels:

“1. At the level of the Deputy Minister, agree on the decision to create a particular product;

2. In three secret institutes, develop a tactical and technical task;

3. Agree TTZ with the developer (co-executors), military representatives, on Znamenka;

4. Conclude a government contract;

5. Prepare thirty licenses, permits, certificates from the district police officer, from the sobering-up station and veterinary dispensary, two suitcases of settlement and calculation materials and a thousand other items on the list - and all this BEFORE you start developing.”

What happens once you’ve finally, after a year or two, obtained permission to start developing a project? Again, our correspondent notes there are certain bureucratic problems:

“- let's all domestic;

- temperature range from minus 50 to 50 degrees for all components, including optics and batteries;

- reliability - thirtyfold. Like the fire detection and extinguishing system of the cruiser "Moskva";

- standardization and unification of a light UAV should be at the level of 90% with the components of the T-64 tank;

- and be sure to catalog everything in the 46 Central Research Institute system, which, of course, is ten times "more convenient" than any online store cobbled together by a ninth-grader in WordPress in a computer science lesson.”

Once you’ve figured all that out, then you’ll have to:

“- make prototypes;

- test under the wise guidance of secret institutions;

- pass state tests;

- prepare production and somehow establish a series;

- You will establish a series under the conditions of separate accounting for the State Defense Order, when you cannot immediately buy everything available on the market at the best price: everything is agreed with the military representative. It's good if you can make a pre-purchase.”

Easier, then, to buy stuff on the Internet.

Our correspondent concludes that the bureaucracy is the problem, and offers some ideas for fixing things (including shooting saboteurs):

“1. Look for sponsors who are interested in winning the war, and not in filling out paperwork;

2. Design as cheaply as possible, without inflating the price;

3. Focus on reliability, manufacturability in production, convenience and intuitiveness of use;

4. Collect in conditional "garages", but immediately a large series;

5. Give ten programmers a normal (Western!) salary so that they develop convenient and well-functioning software;

6. Buy up all the critical electronic component base, as long as there is access to it, form a technical stock;

7. Test with real users;

8. Establish mass training of instructors, and then UAV operators: together with specialists and volunteers, as well as caring military men, organize training courses, fine-tune the tactics of use;

9. Hire professionals who will deliver reconnaissance, aviation destruction, detection and countermeasures equipment by trucks for a ribbon.”

Russia suffers from particularly nasty issues with bureaucracy and corruption, but here too are themes that will ring awfully familiar to drone users in military forces and in civilian government in the West. The slow churn of official technological development. Waiting for officially-approved domestic producers to produce hardware you can officially use, while you know you can buy a DJI product on the Internet that will do what you want, will cost less, and will arrive on your doorstep in two days - security issues and all.

What can we, as observers, make of Dronnitsa, and what it means for the war in Ukraine, and the wider practice of drones in combat? With the full knowledge that the open-source information is woefully inadequate (and I don’t speak Russian):

Dronnitsa demonstrates that small, consumer and DIY drones are becoming a much more tolerated part of Russia’s approach to combat. When the war first began, many experts on Russia and on warfare refused to believe that Russian fighters were actually using consumer drones. These experts assumed - quite reasonably - that Russia wouldn’t take the risk of allowing its troops to use platforms as insecure and unpredictable as cheap consumer drones.

Many assumed that consumer drones would quickly be rendered useless by Russia’s sophisticated electronic warfare technology. But then video after video came out, almost immediately after the invasion, showing Russian fighters wielding DJI Mavics.

Apparently, mobilized Russians can bring their own quadrocopter and night vision goggles to war, but use them only with commander’s permission. t.me/droneswar/3955

— Samuel Bendett (@SamBendett) 12:00 PM ∙ Sep 28, 2022

Now, months later, videos of Russian fighters using DJI drones are almost as common as videos of Ukrainians using them. And while Russia isn’t directly issuing consumer drones to soldiers, it’s not doing much to stop its fighters from using them, either. In fact, a news report from today, September 28th, claims that newly-mobilized Russian fighters will be permitted to bring their own drone from home.

Dronnitsa also demonstrates rapid movement towards professionalizing using small, consumer and DIY drones in combat, even for major powers. Before Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, using consumer drones in combat was still largely considered something of a fringe, weird pursuit. Scary, yes - but also the kind of thing that desperate people with limited resources, like ISIS and the pre-2022 Ukrainian armed forces, were forced to do because they couldn’t afford to work with anything nicer.

In just a few months, the Ukraine War has changed all of this. It’s demonstrated that at least in this conflict, and with these adversaries, small and cheap drones can be very useful indeed. And if they’re useful, that means it’s worth taking the time to get good at using them. No one was particularly surprised to see Ukraine professionalizing using small drones in combat (since they’ve been doing it since 2014). Seeing supposedly-mighty Russia do it?

That was way less expected.