Fridge Magnets and Memory: Part 1

Fridge magnets are more than tacky souvenirs. They're vessels for our memories.

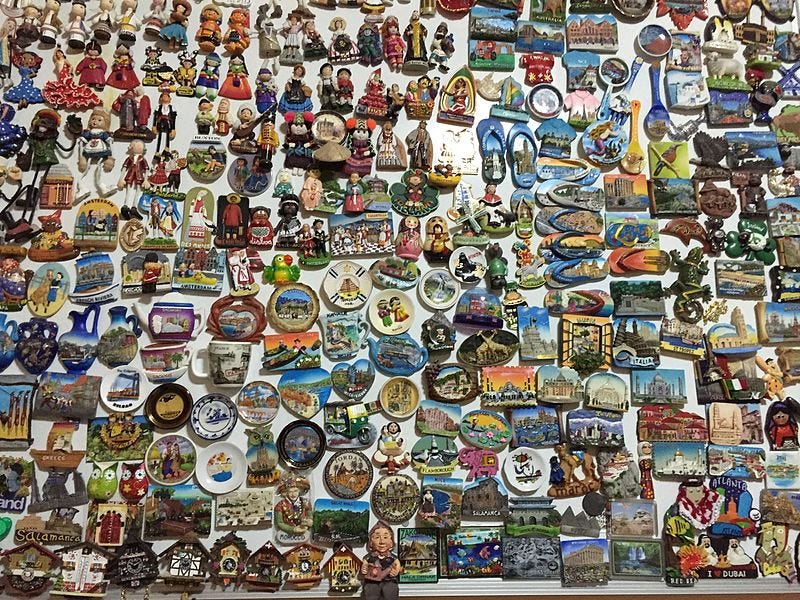

I was getting a glass of water at a friend-of-a-friend’s party when I noticed their fridge. Or rather, what was on it. Every single magnetized inch of it was covered in souvenir refrigerator magnets. They came from every continent and from many of the planet’s better-known islands, and they had been lovingly selected for maximum heinousness. A neon-green palm tree against an ineptly-painted sunsetted sky (for Florida). Plastic simulations of Taiwanese dim-sum and googly-eyed camels. There was a thermometer with the Dubai skyline printed on it, and a wooden depressive looking lion from Kenya, and an Australian boomerang with a startled kangaroo drawn on it . And more, so much more.

I stood there losing myself in my magnets for a moment, imagining the places that they came from, the particular trips that they represented, and also what sort of human being thought that making magnets shaped like screaming lobsters was a path to success in tourist retail.

"My wife collects them from everywhere she goes. She likes them more if they’re ugly,” said the friend-of-a-friend in a resigned sort of way, as he noticed me noticing the magnets. The wife in question was away on business at the time of the party and I knew she was a highly successful, sophisticated person. And yet, she had lovingly curated this refrigerator display of the most disreputable, crapbucket package-drinking-tour souvenirs that I’d ever laid eyes on within a private home. I hadn’t met her, but I felt in that moment as if I understood her a bit. She was the kind of person who travels the world on important business, and returns to her family with the gift of a metallic rainbow alligator magnet that can also open a beer.

Her fridge inspired me, altered my previously untargeted souvenir-buying habits. Today, years after I first saw her kitchen, I too am a Person Who Has Magnets, dozens and dozens of them, taking up every empty patch of metal on my fridge. I buy them whenever I go anywhere beyond my immediate metro area. My magnets hail from dozens of countries and states and cities and tourist attractions, and just like my unseen magnet-hero, I select them for maximum horribleness, luridness, ambition. I have become what Russian magnet-fan Dmitry Balashov called a “memomagnetist” back in 2008,

And yet despite all this passion, I realized recently that I didn’t know anything about fridge magnets. I had no idea where they came from, or who invented them, or why they were ubiquitous in souvenir-junk shops around the entire planet. fridge magnet dates back only to the mid-1960s, yet they are found on every corner of the earth and sold in every souvenir shop and kitchen-goods store on the planet. They are outlandishly successful, and yet I discovered very little has been written on their history or their gigantic popularity.

Here, then, is the origin and current circumstances of that magnetic pink sea turtle you bought in the Bahamas and stuck on your fridge.

The Mysterious And Little-Known History of Your Stupid Fridge Magnet

Fridge magnets have not always existed. In fact, they are probably newer than many people think they are. Just as the invention of the car required the prior invention of the internal combustion engine, so too did fridge magnets require two antecedent technologies: cheap (“permanent”) magnets that don’t lose their strength over time, and home refrigerators.

Humanity has been generally aware of the concept of magnetism for thousands of years, as they observed naturally-magnetized materials in nature. What was trickier was imbuing something with permanent magnetism, which didn’t lose its power over time. In 1930, Drs. Yogoro Kato and Takeshi Takei invented a magnetic compound known as “ferrite,” which was initially used to produce radios. Ferrite magnets were considerably cheaper than the permanent magnets that came before it. In fact, they were so cheap that they could reasonably be used to produce junky souvenirs. (But they weren’t, just yet).

While mechanical iceboxes first appeared in the United States sometime after 1915, they were a fancy, luxury object, the sort of thing you’d purchase to signal your superiority over the poor peasants who still had to stick their perishable food in an old-fashioned icebox and hope for the best.

That all changed in the 1930s, as refrigerators became easier-to-produce and less expensive. Even amidst the misery of the Great Depression, American consumers began purchasing them in droves, attracted by (not inaccurate) marketing claims about how electrical fridges facilitated thriftiness and food safety.

By 1940, 50% of American households reported owning one, and by 1944, that figure had grown to a remarkable 85%. In just a few short decades, the electric refrigerator had become an essential element of the landscape of the American kitchen, an object that pretty much everyone had, or very much wanted to have in the near future. Yet these upwardly-mobile fridge owners of the 1940s and 1950s didn’t have fridge magnets. They hadn’t been invented yet, in large part because these early fridges often weren’t made with materials that magnets could stick to: many were finished in porcelain or plastic or wood.

As time went by, American fridges began to grow more expansive in size, objects (available in charming avocado, harvest gold, or pink colors!) with ever-more unused space to put junk on. By the 1960s, the souvenir fridge magnet had both a cheap mechanism for sticking-to-things and a natural habitat. It just needed someone to invent it.

We like it when we can attribute the invention of a certain object or idea to a single human being, a solo genius struck with a sudden and remarkable flash of genius, a Great Man (and it is almost always a man) who rattles the course of history with his muscular ideas about automated can-openers or the cotton gin or drive-through fast food restaurants. And so it goes with fridge magnets.

Most sources, from academia to the Internet, attribute their invention to a man from St Louis named William Zimmerman, owner of the Magic Magnets company. As the usual, uncritical Internet story goes, Zimmerman at some point in the early 1970s patented a set of magnets that depicted cheerful cartoon characters, an innovation that would permit harried American families to hang up crayon drawings and stained takeout menus in a convenient nose-level location. It’s a superb little story, a pleasant mid-century Horatio Alger tale. It was also shockingly difficult to prove true.

I began my hunt for William Zimmerman with Google’s patent search, where I assumed that his great fridge-magnet-with-a-dog-on-it patent would pop up. To my surprise, I ran a search through their patent records for “William Zimmerman” and “refrigerator magnets” and came up totally empty-handed. The only patents on record granted to any William Zimmerman dated back to the late 1800s and early 1900: this particular Zimmerman was an ingenious sort of guy who had invented, among other things, a new kind of folding bed and something called a “smut-machine.”) But no magnets.

I could find nothing else on Google, or Google Scholar, or in newspaper records, and there were a lot of people named William Zimmerman wandering around the country doing newsworthy things in the 20th century. By this point, I had spent dozens of hours trying to hunt William Zimmerman, to prove that he had existed and fiddled around with magnets one way or another. I get sucked into these hunts for one-or-another poorly documented person on the Internet, sometimes. I guess it feels, in a way, like I am paying homage to their memory, doing my small part to ensure that they are not totally expunged from the world as I hunt for evidence that they really existed.

Then, it occurred to me that I should figure out when people first started talking about Zimmerman and his magnetic inventions.. On November 21, 2006, a Wikipedia user identified only by their IP address added a paragraph of information about William Zimmerman to the encyclopedia’s entry for “Fridge Magnet.” This person claimed – without citation - that Zimmerman not only patented the first fridge magnet in the early 1970s (which is well after the first fridge magnets I could find were produced), but that he “patented the first hi-fi record brush in the 1950s,” then used the proceeds from its sale to RCA to purchase two St Louis theme parks.

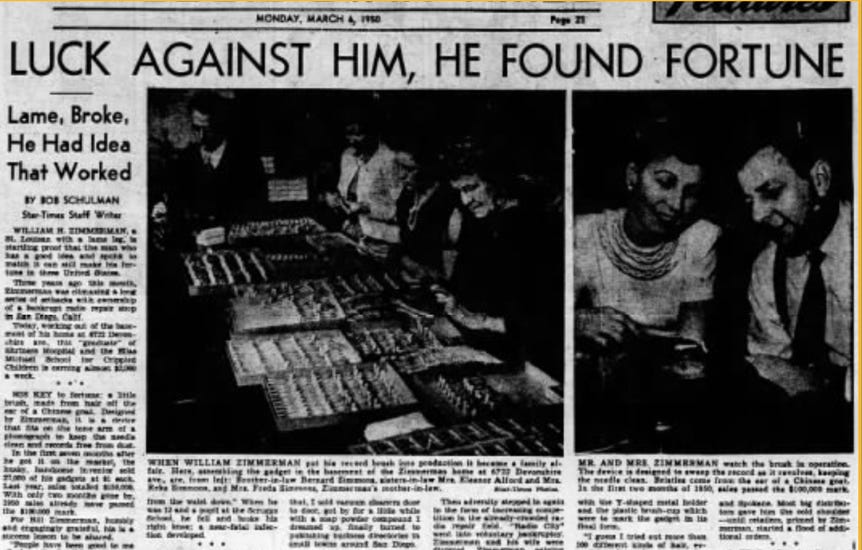

The theme parks. Finally, I was getting somewhere. I found that someone named William Zimmerman really does seem to have co-owned a couple of amusement parks in St. Louis, and I was able to find a 1948 patent for a magnetic “phonograph pickup arm” attributed to a William H. Zimmerman, and a St. Louis based record-brush firm named the W.H. Zimmerman Co. Amidst all those long-dead newspaper scans, I found a 1950 St. Louis Star-Times newspaper article about his record-brush exploits, and it even came with a photograph of the then-30 something Zimmerman and his wife.

The paper described him as a formerly “lame and broke” man who had turned into a “husky and handsome inventor,” a scrappy survivor-type who had suffered a serious injury to his hip as a child that left him with a permanently stiff leg. He’d spent much of his youth in California trying everything from door-to-door vacuum sales to working in an aircraft factory, up until he came up with his great idea about record brushes (which were made with bristles improbably sourced “from the ear of a Chinese goat.”)

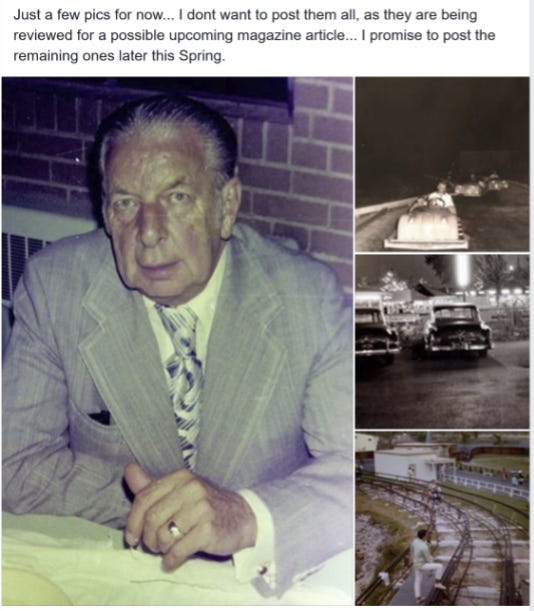

So William Zimmerman had lived in St Louis, and probably knew something about magnets, but I still couldn’t find any evidence that he’d done something with the kind that go on the fridge. Until I came upon a Facebook page dedicated to Holiday Hill, one of the long-since dismantled theme parks that he used to own. Dozens of people posted photographs of the theme park and the people who ran it, and one of those people had posted a sepia-tinged photograph of William Zimmerman, taken sometime in the 1960, unmistakably the same man as the one in the 1950 article.

He was sitting in a grey corduroy suit that looks a lot like one my own grandfather had in the 1970s, looking pensively at the camera. This William Zimmerman was older and fiercer- looking than the fresh-faced 30-something embodiment of the America dream, the one that the newspaper had photographed hunched over a magnetic phonograph arm in his living room in close, shoulder-contact with his pretty young wife in the 1940s news story. But he had been loved, admired. People in the Facebook group wrote affectionately of Bill, how he’d been a tough-boss-who-was-fair, the sort of guy who genuinely cared if you enjoyed your trip to the theme park in the dead heat of a 1970s summer. They remembered him, and to my indescribable joy, a few of them also remembered his goddamned magnet.

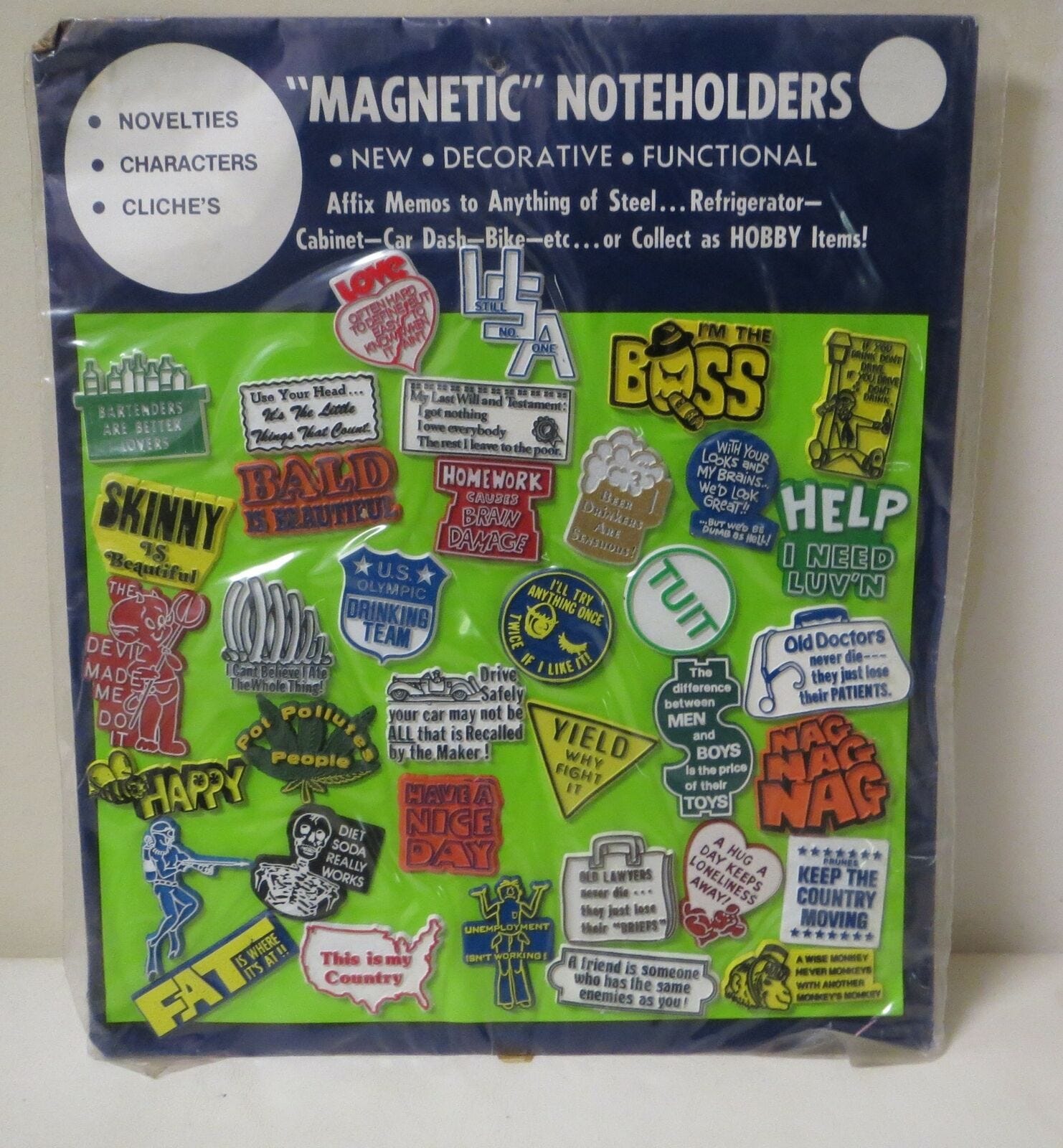

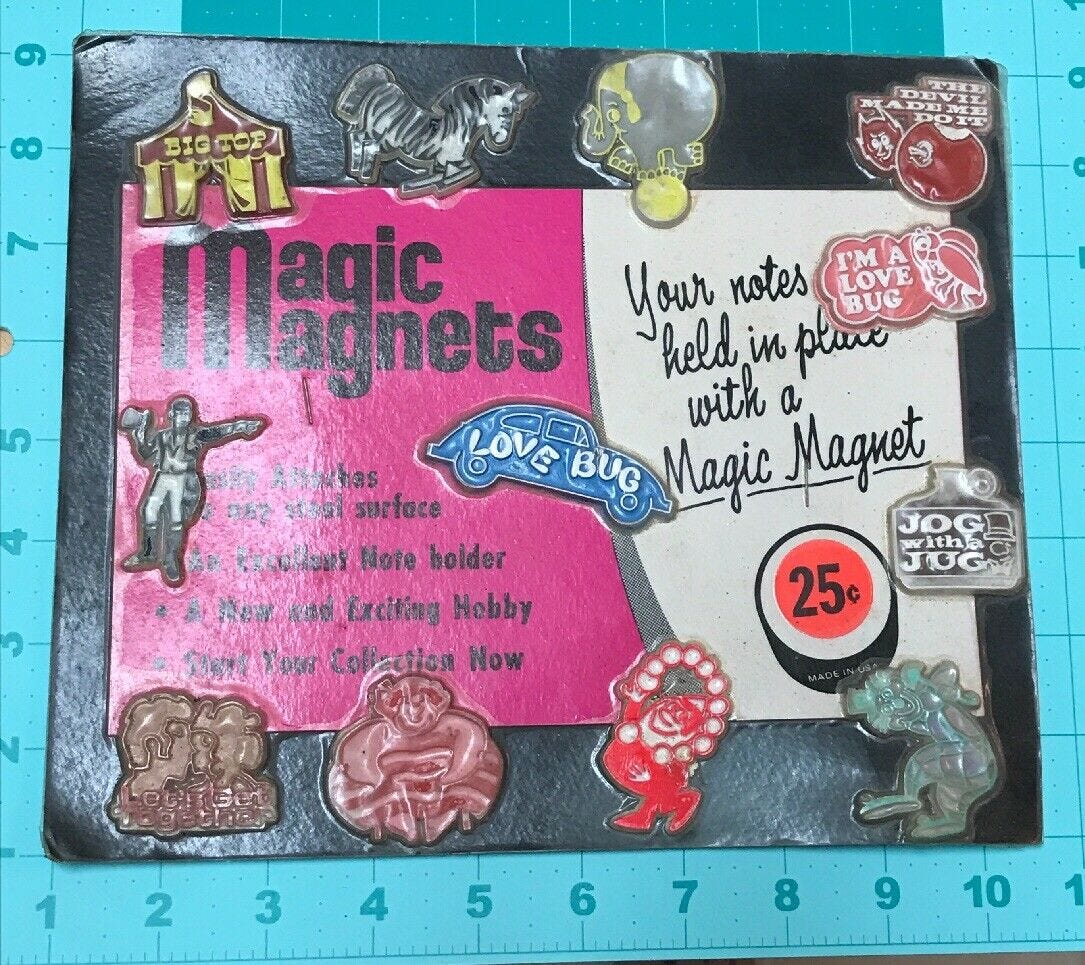

In the Facebook group, a man who identified himself as a family member wrote about how his Uncle Bill paid for his portion of the park with the proceeds from the magnet business. It was called, he wrote, “Magic Magnets,” it was founded in the early 1970s, and he still had boxes of them floating around interminably in his garage. I knew what that name was, because they were the same flat cartoon magnets with then-hip 1970s catchphrases (“Pot Pollutes People,” and A Hug a Day Keeps Loneliness Away,” or worrisomely contradictory terms like “Skinny is Beautiful” or “Fat is Where It’s At.”) on them that I’d seen floating around eBay and Etsy. They were, in a way, weird little 20th-century proto-memes.

According to this family source, Zimmerman even scored a contract to make the very first refrigerator magnets for the Walt Disney Company, an extremely early manifestation of the souvenir magnet. His Magic Magnet packaging optimistically called his slogan-magnets a “new and exciting hobby.” Perhaps he was envisioning a future where ruddy-cheeked American children swapped magnets with pictures of beer on them like valuable, golden contraband.

This never happened, not really, but you can see the ever-entrepreneurial Zimmerman could imagine it, in the same way he’d imagined his phonograph brush and his theme park. Unfortunately, per the family member’s Facebook posts, William’s son Ray betrayed him. He made off with his father’s client information and formed a rival magnet company, and managed to land a lucrative official contract with the Peanuts comic strips. Magic Magnet products in Zimmerman’s style stop appearing on eBay by the 1980s, and I have to assume that is when the business closed.

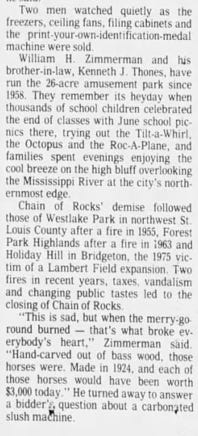

I found a news story about the closure of the Chain of Rocks amusement park in 1978 describing the final auction of the park’s assets, the selling-off of Ferris wheels and freezers and the various small architectures of theme-park entertainment. Near the end of the piece, the writer describes two quiet men, looking at the proceedings with grim, resigned faces. It was William H. Zimmerman, watching the park be dismantled: he and his brother-in-law and co-owner had to give up on the place, after a succession of fires and vandals and diminishing returns. “This is sad, but when the merry-go-round burned – that’s what broke everybody’s heart.” Zimmerman tells the reporter. Then he turns away “to answer a bidder’s question about a carbonated slush machine.” His obituary was published in May of 1992. He donated his body to science, and requested no visitation.

Somehow, William H. Zimmerman is both remembered by the Internet, and also quite thoroughly forgotten. In the eyes of Wikipedia and thus the greater Internet, he is the father of the fridge magnet. Officially, in the eyes of historians and academics and people-who-care-about-sourcing, he barely existed. While his status as the father of the Fridge Magnet almost certainly derives from Wikipedia, it’s not there anymore. An editor expunged the mention of William Zimmerman from the fridge magnet Wikipedia page way back in 2012. He has almost been swallowed up by his Internet invisibility, and he may still yet be. But here it is. William Zimmerman existed, and he made lots of magnets in the shape of zebras, beer steins, and Disney characters.

But did he invent the decorative magnet? While Zimmerman may have been one of the first people to see the fridge magnet’s potential as a message or meme-carrying device, he wasn’t, as I learned, the first person who thought of making them decorative.

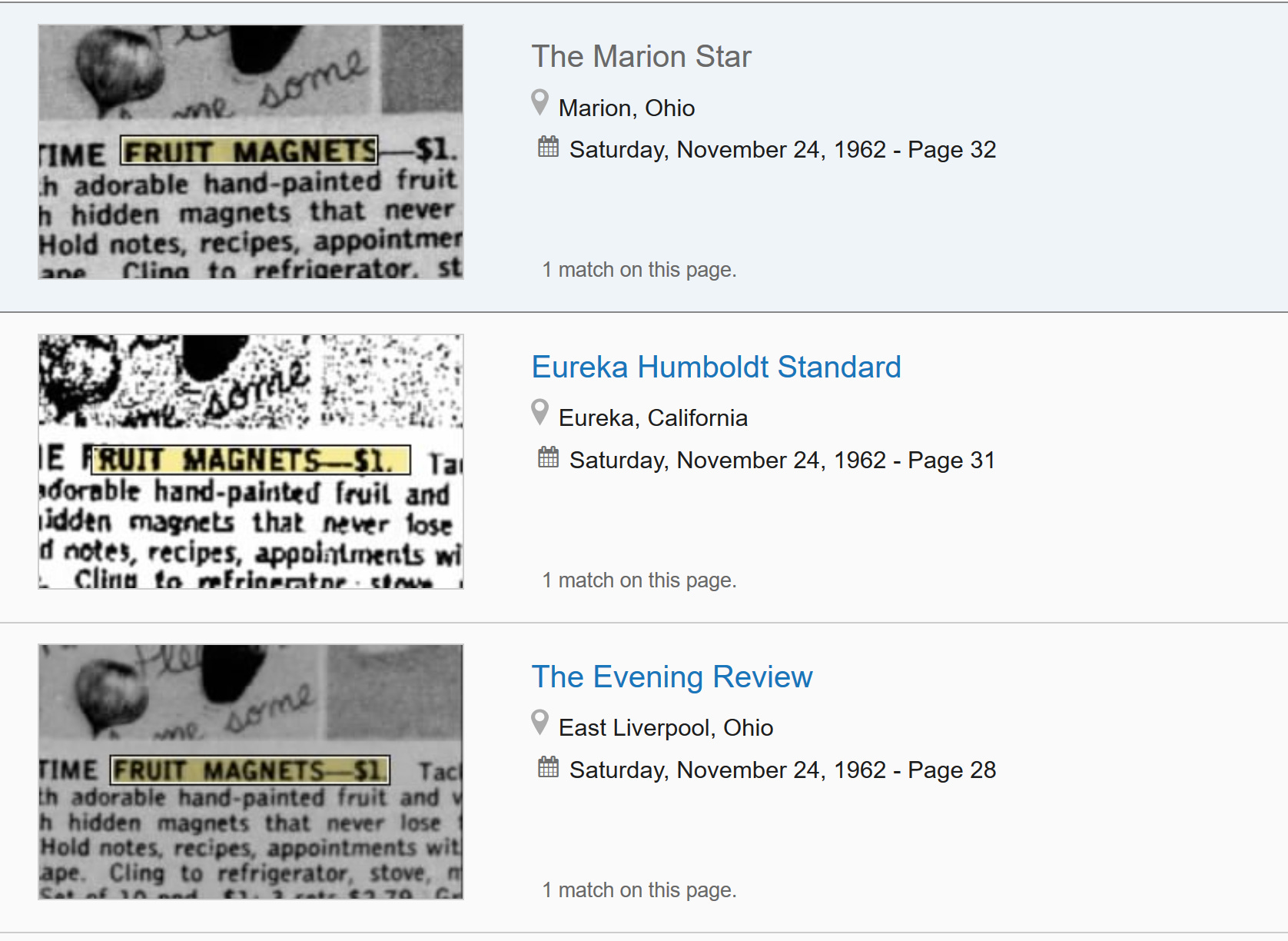

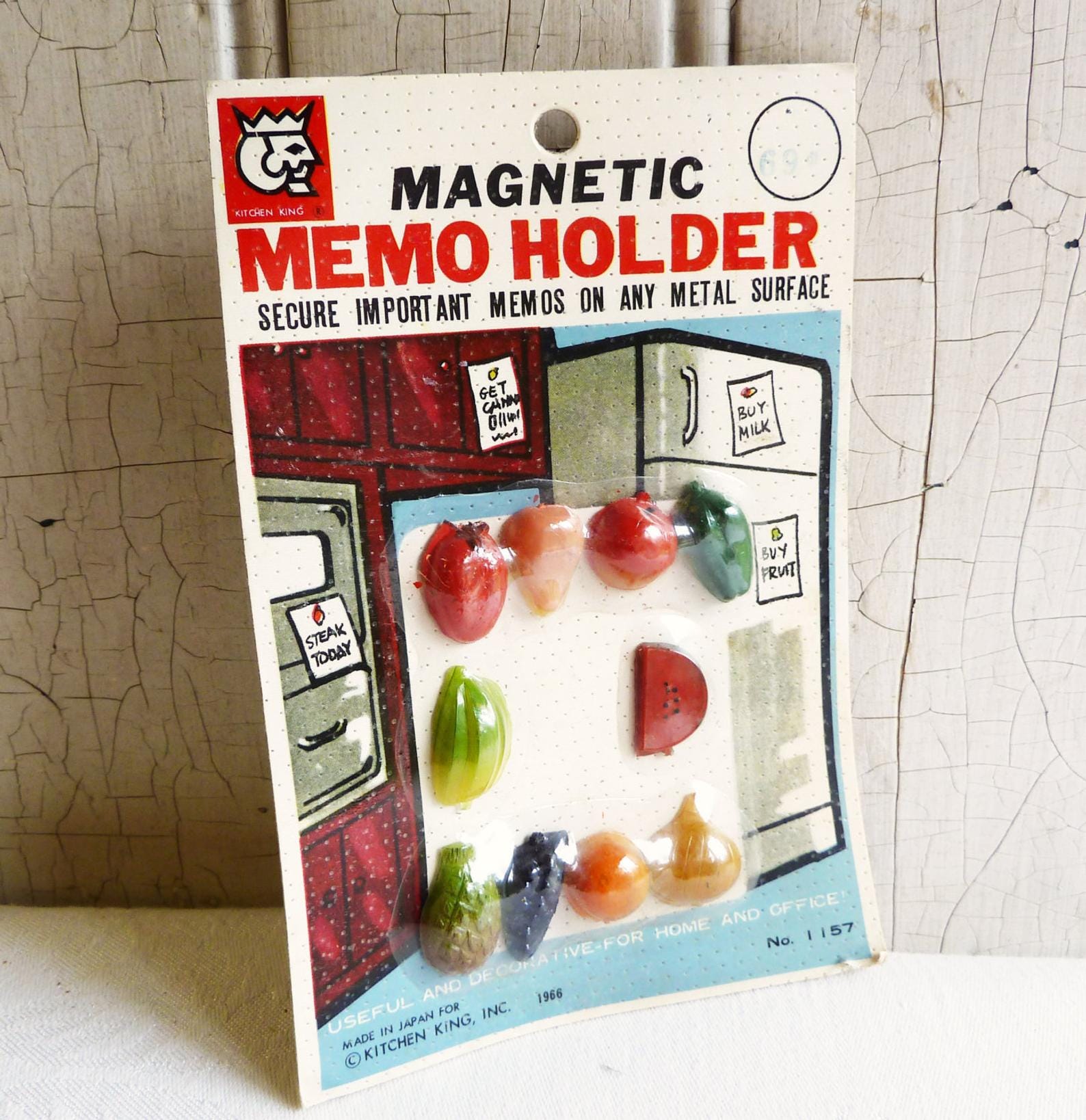

In 1954, one Oren Whitwell submitted a US patent application for a magnetic memo holder, which could be stuck onto any suitable metal surface. Magnetic memo holders then begin to creep into existence, although they were rather industrial-looking affairs. The oldest decorative fridge magnets I could find physical evidence of date back to the fall of 1962, as you can see in this image above. That’s well before Zimmerman’s Magic Magnets came on the scene around 1971. They’re also fruit-shaped, which means that the fruit-shaped magnets that so many of us vividly recall in our grandparent’s kitchens are probably the primordial ur-magnet from which all others descend.

These early fruit magnets were advertised as “decorative magnets” or “memo-holders,” and they were manufactured in Japan or in Hong Kong, than sold to U.S. markets from distributors based in New York, New Jersey, and California. I have to assume that the true inventor of the decorative fridge magnet was thus someone located in Asia, a person whose history is, sadly, even more cryptically documented than William Zimmerman’s is.

There is another Great Man in fridge magnet history, another nameable person who realized that sticking pictures on the fridge was highly marketable. His name is Sam Hardcastle, and unlike William Zimmerman, he is backed by plenty of reasonable historical evidence, as well as an origin story printed on his own website. Hardcastle was also a native of St Louis (did he and William Zimmerman have some sort of magnet feud, did they glare at each cuttingly at local restaurants?), and in his case, he began to work with magnets at the behest of NASA.

In the mid-1960s, the space agency entrusted Hardcastle with creating a special sort of flexible magnet for their displays and for planning purposes: the entire body of these magnets could stick to things, instead of a just a small portion of them which had been glued to something else. Hardcastle devised a process for creating molded, inexpensive magnets, and as NASA’s demand increased, he began to print them with more colors and in different shapes.

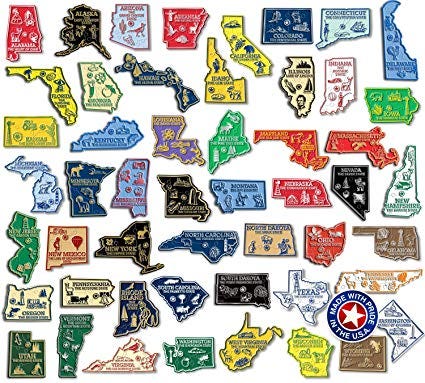

By the early 1970s, Hardcastle noticed that a molded inexpensive magnet you could print stuff on was a highly marketable thing, and he founded Ad Specialties, a company devoted to turning out promotional, collectible magnets. Soon, his company began to sell molded magnets in the shape of all 50 states, designed specifically for the souvenir industry. It is these state magnets – which Hardcastle’s current company still produces, in unchanged form, today - that may hold the key to the entire universe of location-based souvenir magnets that are with us today. Beside Zimmerman’s Disney magnets (which are more about characters), they are the earliest example I could find of a true souvenir-magnet, the magnet linked to a specific place in the world, a magnet with a sense of location.

Hardcastle’s state-magnets signified that you’d been somewhere, that you’d gone somewhere. They fulfilled the same function as travel postcards, or souvenir shot-glasses or little collectible spoons with pictures of Washington DC on them: a memento both to jog your own memory, and to signal to everyone else that you were the sort of person who occasionally left town.

Magnets-as-souvenirs were even better than spoons or shot glasses or postcards, though. They were dual purpose-objects that stuck to the fridge and could hold up take-out menus and photographs, and you could place them right at the level of your nose where you could see them every day as you fumbled around for milk in the morning. Most importantly, they were cheap.

During the 1970s, refrigerator magnets shifted from somewhat-novel to totally ubiquitous, the kind of thing that everybody owns and that nobody actually notices without conscious effort. In the process, the American refrigerator its transition from smooth-surfaced kitchen appliance to an early form of social media, a collective family bulletin board. Zimmerman’s Magic Magnets, Hardcastle’s Ad Specialties, and the Chinese and Japanese magnet-makers were just one of hundreds of companies seeking to capitalize on the Nixon-era magnet rush.

The state-magnets produced by Hardcastle caught on, and many other companies began to churn them out in vast quantities. During the 1980s, per the eBay historical record, souvenir shops began to stock crab shapes and ice-cream shapes, bikini girls and little Eiffel Towers, everything someone could make out of plastic or resin and magnetize.

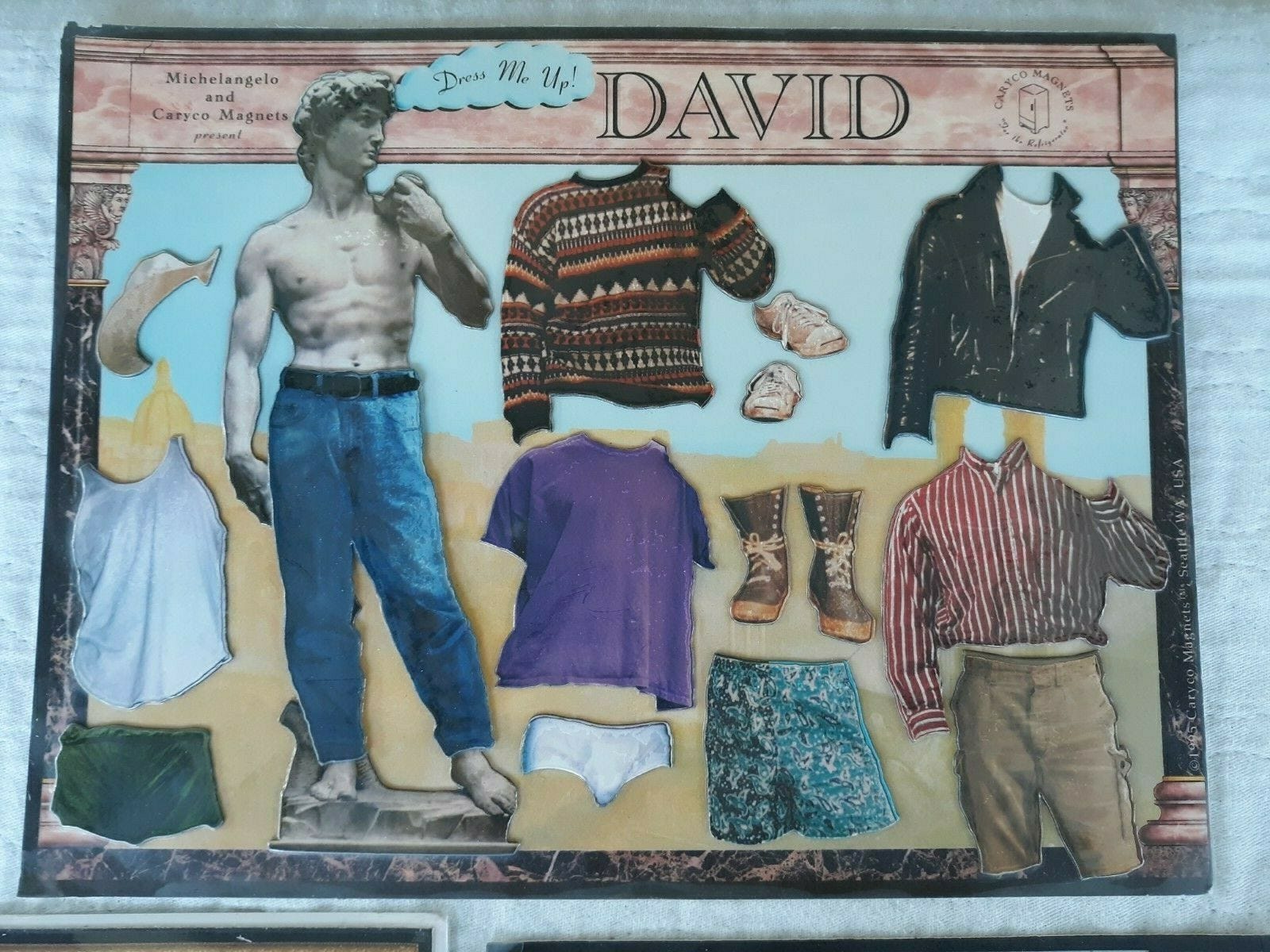

By the 1990s, the formerly small-potatoes magnet business had begun to consolidate. It grew harsher. Hardcastle’s website ruefully notes that Chinese companies in this era produced souvenir magnets in volume that US manufacturers could never hope to keep up with. Nineties magnet-makers began to produce edgy magnets, magnets for the jaded Gen-X type who couldn’t abide by their grandparent’s despicably cheerful fruit.

You could buy a fridge version of Michelangelo’s Adam with discrete boxer shorts over his petite white-marble junk that you could dress up with magnetic clothing, or little resin dog and cat butts to stick on your wall, or greeting cards for people turning 60 with glued-in magnets that helpfully reminded them that they would die sooner rather than later. The 1990s also saw magnetic poetry sprang onto the scene, and for a while, people became very good at writing out magnetized innuendo for their loved ones and roommates to contemplate while they stirred their coffee.

Today, most souvenir fridge magnets are made in China, then sold onwards to airport news-stands and souvenir shops around the globe. Souvenir sellers either work with importers to create their own customized designs (a happy sun over a lake, a resin state of Texas with a real thermometer inside of it, a starfish wearing sunglasses), or simply purchase a design that already exists, adding to a great collective of tacky tourist art.

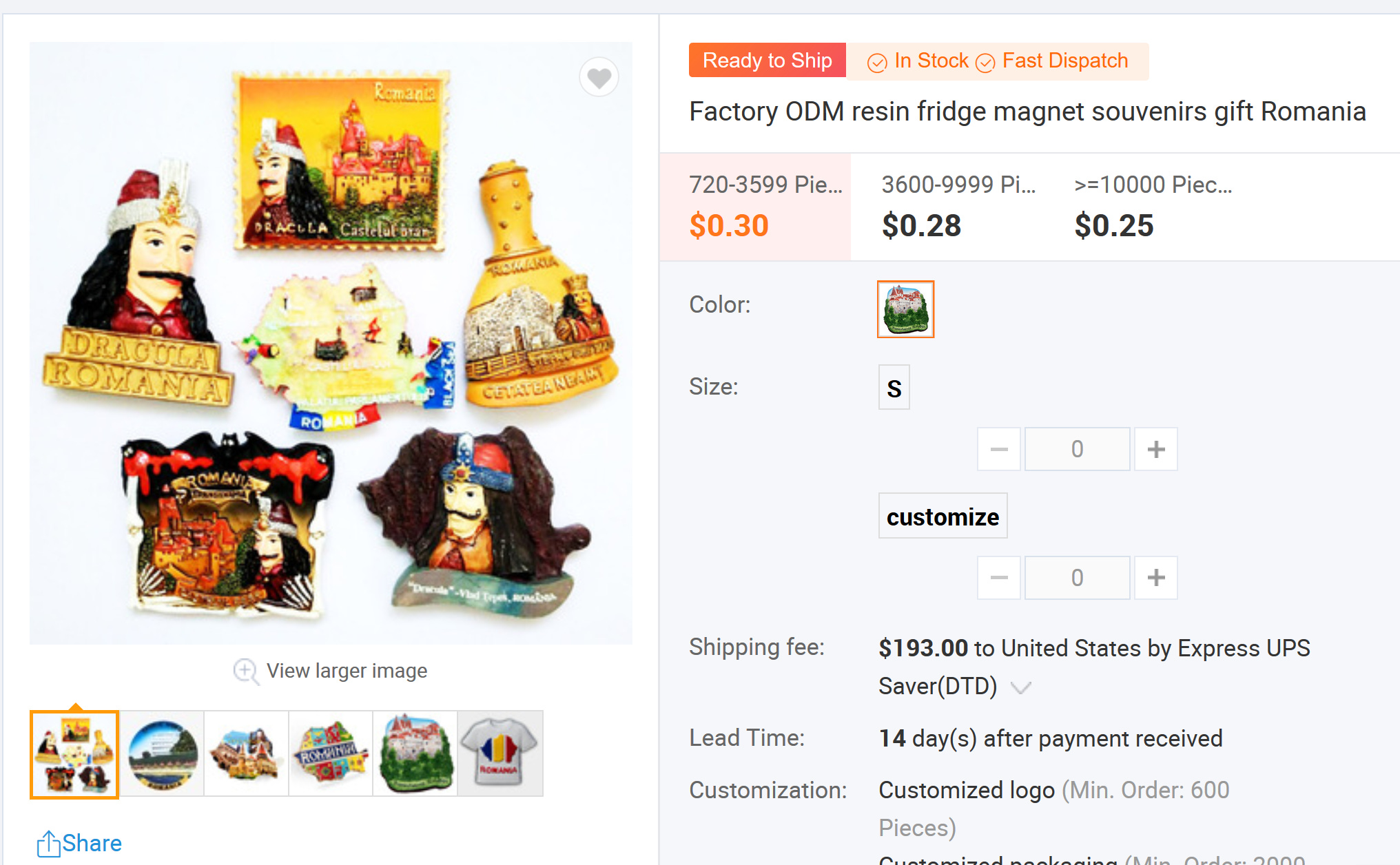

The GlobalSources website offers over 3000 styles from 463 manufacturers: for example, a Chinese-made "soft rubber 3D" fridge magnet for the Saudi city of Riyadh retails for between $0.1 and $0.6 each, for a lot of 100. Just about ever souvenir magnet ever made for every location on earth is available from Alibaba: there, you can buy 1000 rubber magnets advertising the Iraqi city of Basra with a smiling camel on them, or 720 resin fridge magnets for Romania with Vlad the Impaler on them.

Fridge magnet collectors, too, have become recognized as official weirdos in our culture.

Consider Louise Greenfarb of Las Vegas, who holds the Guinness World Record for the most fridge magnets. She had over 50,000, which stretched across her house in a colorful resin-based stream. Or contemplate Welshman Tony Lloyd, who has somehow socked away over 3,600 of them. Per this Wales Online feature on his exploits, he loves “geographically informative” magnets but shuns anything “cheap or tacky.” In the story, he decries the fact that in “Windsor and London they have teddies dressed as kings and queens. It’s an abomination.”

That brings us to the present. And to me, and to you, and to anyone else who’s ever dropped a few bucks on a fridge magnet.

So why, then, do we like them so much? What gives this simple souvenir such, well, sticking-power? What makes a memomagnetist? I will cover this in the second essay in this series.