Fridge Magnets and Memory: Part 2

Fridge magnets are our memories, in the form of plastic alligators.

Souvenir magnets are our memories, transformed into the form of a dumb resin crocodile that we can put in our kitchen.

Let’s consider my very own collection of kitchen crap-magnets.

One of my favorites is a horribly realistic-looking plastic slice of Key Lime pie that I bought at the Tampa airport in Florida, the state in which I was born and traveled to every year of my life – up until 2017, when the last of my grandparents died and I stopped having any real reason to return.

I picked up the key lime pie magnet that year as I waited for my last flight out. I bought it in part because of how unsettlingly natural it looks, an occupant of the food-magnet uncanny valley. I also bought it because it reminds me in exquisite detail of the Publix key lime pie that my grandparents would always have magically waiting for me in their unmagnetic and naked fridge at their house whenever I visited. I also, also bought it because that house in Tampa had an ancient set of 1970s fruit-shaped fridge magnets stuck to the boiler in the garage, where I would rearrange them into the shape of a mutated dog every time I visited, and every magnet I own reminds me of that small act of expression.

Then there’s the beer-opener magnet from Doha, which I bought because I found it amusing that a mostly-dry country would sell me something like that. There’s the magnet in the shape of a startled, fuzzy llama that I bought at the market in Peru in 2018 as I wandered around on a gloomy Lima winter day, and there’s the magnet from Devon in the UK that I purchased at a souvenir shop in a reputedly haunted town on a spooky-looking moor.

You get the picture. Which is this: every single one of my magnets has a narrative attached to it.

Every time I look at them, every time I open the fridge to rummage through it for cheese, I press a little replay-button in my brain. I am reminded of things. I could, if I was very obnoxious, write an entire autobiography of my relatively short and uneventful life based entirely upon my fridge junk.

I am not the only person who’s noticed how souvenirs like fridge magnets facilitate our memories, how they function as a sort of pre-Internet social media (albeit for the consumption only of ourselves and whoever we let into our kitchen). Academics call this phenomenon “mimesis,” a representation “of the real world in art or literature.” Fridge magnets are thus a symbolic stand-in for the real thing that is our memory and our experience, a visual cue.

Meanwhile, the word “souvenir” is defined generally as “a thing that is kept as a reminder of a person, place, or event.” Today, we use this word almost exclusively to refer to things you buy when you’re away, at at least some distance from home.

While souvenirs have become more common and visible with the advent of mass leisure travel, they are, in their function as prompts for place-based memory, extraordinarily ancient objects. In 2019, archeologists dug up an ancient Roman stylus, which had been buried for millennia beneath London. The Latin inscription on the artifact can be translated like this:

‘I have come from the City. I bring you a welcome gift

with a sharp point that you may remember me.

I ask, if fortune allowed, that I might be able (to give)

as generously as the way is long (and) as my purse is empty.

The meaning here is clear. We’re looking at the ancient version of “I went to Rome and all I got you was this lousy pen.”

While our ancient ancestors might not recognize the modern fridge magnet, they would likely recognize the idea behind them. They are cheap and readily-available objects that you buy while you’re traveling to bring home. They make you think of, or remember, something.

A 2017 Dutch study examined how people respond to items they brought back from vacations in their homes. In it, they asked people to select items in their homes that were related to the holiday, and then the researchers asked them what the object made them think of, if they thought of the thing as a memory cue.

Five of the respondents chose fridge magnets as items that inspired them to some degree to remember how things were during a specific time during their vacation, or the specific way they felt when they were away from home (the smell of the desert sagebrush, your spouse’s far-away expression as they looked out over the rim of the Grand Canyon, that time you squashed an innocent armadillo with your rental Saab somewhere near El Paso).

Although these memory-evoking responses might be dulled if they saw the fridge magnets every day, the research subjects could, if prompted, associate specific memories and stories with them. In other words, their research validated my personal experiences. Fridge magnets held the potential to trigger memory.

Fridge magnets also are objects that are rooted in a sense of place.

In"On Longing," Susan Stewart writes that the souvenir exemplifies object's capacity "to serve as traces of authentic experience.” Souvenirs are objects that represent not the experience of whoever made it, but the 'secondhand' experience of the person who bought it. A souvenir is, by definition, always somewhat incomplete. It is an imperfect remnant of an experience in the past, a reminder in the form of a plastic sparkly lobster.

Per Stewart, the souvenir "displaces the point of authenticity as it itself becomes the point of origin for narrative."

Thus, souvenirs are intrinsically linked to a specific place, a specific location because of your memory of buying it in that particular place - even though almost all fridge magnets and similar souvenirs are mass-produced, non-unique objects. The souvenir, Stewart writes, only acquires value "by means of its material relation" to the location in which we bought it.

Philosopher D.M. Lasusa, in a paper exploring the philosophical meaning of souvenirs, has a somewhat similar take on the matter. Lasusa writes:

“Cheaply made and mass-produced souvenirs are not thought to have intrinsic worth, and are consequently not recognized by the general public as valuable, but they do become meaningful—for various reasons—for the tourist who proudly displays it on the fireplace mantel. The meaning of these pieces is flexible and dependent on their relation to personal and public environments, stories, myths, beliefs, and values.”

In the context of magnets, this is why I would never dream of ordering souvenir magnets in bulk online, or purchasing one from a thrift store. What would be the point? I like my magnets because they are specifically associated with my own experiences and memories, not just because it's fun to look at googly-eyed crocodile beer openers (though of course, that is also very fun indeed).

My magnets hold little to no intrinsic value. No one will be selling them on eBay for untold gazillions after my death, and there is no booming trade in rare fridge-magnets in well-respected art museums (at least, not yet).

They matter to me and exclusively to me (and perhaps some of my family and friends) because they are visual reminders of my own narrative, my own travel-story. Per Lasusa, they are a means of building a “concrete archive of personal history.”

She writes that souvenirs “offer a way for the tourist to prove to himself or herself that an experience was not simply an elaborate hallucination or dream, but actually part of one’s life and history. They are a way of making one’s life and memories “real.’”

Of course, my rule about magnets-only-matter-if-I-buy-them isn’t set in stone. There is flex room, as there is in most human affairs. My partner buys magnets sometimes when traveling abroad, in part for himself and also for me, and these objects retain more meaning to me than a magnet I bought in a thrift store. Perhaps that’s because he is close to me, and he tells me in great detail about what he did in those places, and those stories are at least adjacent to my own.

Still, I would never want most of my magnet collection to consist of magnets I bought later, after I had already returned from somewhere, or that someone bought for me. There is still great value to the exact moment of purchase.

The Dutch researchers I mentioned above found that people often associated multiple memories with their travel souvenirs (including magnets), and so it is with me. I have a Dutch porcelain magnet in the traditional blue-and-white style with a painting of a windmill on it, and when I think about it, I recall both the experience of visiting the Netherlands in the late summer of 2018 and the associated overall feeling about it (those frightening late-night swans, the Indonesian food).

At the same time, I remember the moment when I bought it at the Amsterdam airport, amidst a wonderful sea of shot-glasses covered in pictures of marijuana leaves, mugs in the shape of human butts, and t-shirts bragging about the exact level of wastedness you achieved during a bender weekend along the canals. It’s a complex dual memory, and it’s one that gets evoked whenever I linger too long by the fridge and the blue-and-white catches my eye.

I do not need my magnets to be exotic, in the sense that I will only buy them in places that are truly foreign to me, outside my experience. I do not need to be on a Vacation or an Expedition of some kind to want them, for them to perform their memory-jogging function. While I do not need to evoke memories of Boston right now, as I'm currently living there, I don’t plan to live here forever. (I hate winter). I will want a memento or a reminder of living here someday, and that is why I own a plush magnetized lobster and a magnet with a picture of an 1800s Boston "Strong-Boy" body-builder on it. I own them to hedge my bets against the future. To return again to Susan Stewart, magnets and all other souvenirs work because they evoke both a time and a place, a location.

I recently came across a home design blog post pitched to the sort of people who aspire to potpourri-scented home immaculateness in Instagram pinks and grays: the article tut-tutted at people who cover their fridges with magnets and paper junk. “If you’ve got a fridge covered with magnets and papers, your kitchen is a mess,” wrote the blogger. “It's the kind of mess you can get used to, but it's the first thing people notice when they walk into your home.”

This gets at something else worth noting about fridge magnets: they are not classy, or aspirational, or “nice.” They are kitsch, crap, junk, a guilty pleasure.

The refrigerators one sees in television commercials and home design blogs like the one I’ve quoted here are usually entire nude, unadorned. If any magnet is suffered to live, it will be unobtrusive, solid-colored, and purely functional: a memo-holder and nothing more. If design magazines are anything to go off of, we are meant to believe that fridge magnets are declasse, downmarket. They’re the sort of thing you might want to shove hastily into a shoebox if your shitty boss with pretensions comes over for a drink.

According to this world-view, the exterior of your fridge is a reflection of the interior of your person, and (logically) your inner self should not be bristling with plastic crap that strategically hides the weird brown stains on the door. To apply this to my own situation, while I may have all manner of deep memories wrapped up in my rubbery plastic manta ray magnet from Belize, to an outside observer, it’s just a plastic and dead-eyed sea creature stuck to a stained fridge.

Even some ardent magnet collectors pass this sort of aesthetic judgement. Recall again that Tony Lloyd, Europe’s pre-eminent collector, told Wales Online that he abhors “cheap and tacky” magnets, and called the existence of teddy-bear shaped magnets dressed like royalty an “abomination.”

I am, of course, not of the naked-fridge school, or even of the school that prefers my fridge magnets to be classy. I desire a souvenir fridge magnet in direct proportion to how utterly horrible-looking, how lowbrow it is. My magnet hunt revels in the terrible, but that is why I love them. They are kitsch, but my relationship with them goes further than that.

Susan Sontag wrote her famous essay “On Camp” in 1967 – which is, coincidentally, about when fridge magnets first became common - and there are many insights there for the magnet-collector. “The essence of camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration,’ says Sontag. “People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as ‘a camp,’ they’re enjoying it. Camp is a tender feeling.”

The ultimate Camp statement, per Sontag is that something is “good because it’s awful” under certain conditions – and so, is exactly how I feel about magnets. I do not love them ironically, with an implied sneer. (And even if I had loved them ironically at first, a thing that a person loves ironically usually becomes something a person loves genuinely). I love them with a certain level of knowing sincerity, and I appreciate people who like them, too. A person who came into my house and sneered knowingly at my magnet bottle-opener from Provincetown in the shape of a yelling lobster would never be invited back again. They would have proved that we have nothing much to say to each other.

I have had many good things to say about fridge magnets, but it is also true that they are not always innocent.

Like so many souvenirs, the fridge magnet walks a razor’s edge between cheerful, friendly tastelessness and something darker, crueler, more grotesque. As I’ve mentioned, all souvenirs, from crocodile-skin ashtrays to flamingo picture frames, are inescapably linked to place, to a specific location on the map. They are objects that attempt to symbolize an entire location and a culture into a single thing.

That is, of course, a very dangerous game to play.

This distillation of every single thing that matters about a real place into one object you can buy for $5 at the airport is why some people reject the entire idea of souvenirs. They are repulsed by the entire concept of taking home and displaying, trophy-like, a little chunk of somewhere you went – which, to them, implies that the buyer thinks that they can own places and cultures that are not their own.

The problem of capturing the essence of a place, of somehow visually summarizing it, is the fundamental challenge that fridge-magnet designers and sellers face. They need to offer a range of different little junky things to their assumed tourist customer. They know that some people will feel their trip is best summarized by the spring-loaded flamingo that jiggles (me), while someone else (the high-faluting Lloyds of the world) will want a tasteful metal dolphin, and someone else again will want a resin alligator drinking a beer (also me).

The souvenir-makers further knows that human beings respond well to stereotype, even nasty stereotypes that are offensive to many of the people that actually live in the place they’re visiting,. And so, too often they decide to appeal to the basest, stupidest instincts of their customers. The tourist stores in Palermo, Sicily sell amusing resin-seafood magnets and those that look like Mt Etna which are the ones I bought. They also sell magnets in the shape of tiny mafiosoes with guns. I’ve seen the same pattern ring true around the world, where souvenir shops sell items that would likely be actively offensive to many of the locals.

Often, these broad-brush cultural stereotypes are linked to frat-boy, Facebook-memes shared by your skeevy middle aged uncle levels of humor. Amsterdam and Las Vegas, known for their party cultures, excel on this front. In these cities, you can buy magnets in the shape of boobs, butts, joints and pot leaves. You can purchase a magnet that brags about exactly how drunk and high and unruly you got while you were on your vacation, there for all your friends to see.

In Cambodia, you can buy magnets that say "No Money, No Honey" on them (the meaning is probably obvious), and every destination with a beach seems to feature at least one magnet printed with pictures from the mid-1980s of platinum-blonde and aggressively tan women in tiny neon-colored thong bathing suits, displaying their butts seductively to the viewer.

The magnets on offer at a store are, ultimately, what someone wants me to see. Whoever made them is explicitly attempting to offer me a number of different representations of my own memories of the place, my own narrative in the form of a cheap and tiny physical object.

Still, I don’t know who the person making them is, really, or how representative they are of the place, or if they are just like me, an outsider looking in. A magnet-store is just a reflection of what the people selling magnets want you to see about a place. In the end, they would like you to appreciate what you see so much that you give them $5 (with tax).

The souvenir, writes Dr. Rasusa, is something that we collect because we, as modern people, as Westerners, as people with neuroses who “refuse to trust the fallibility of memory” have turned to tourism as a bid for finding meaning in our lives. We are afflicted with what Derrida called “archive fever,” a mania for proving we existed, now only inflamed by the rise of social media.

Yet fridge magnets are highly imperfect vehicles for memory, much less for being remembered by others. As Susan Stewart writes: “The souvenir is destined to be forgotten; its tragedy lies in the death of memory, the tragedy of all autobiography and the simultaneous erasure of the autograph."

This is a tragedy that comes for us all eventually, one way or another. The memories I associate with my magnets have a time-limit on them, as I, as an unfortunately mortal creature, have a time-limit on me. The memories I associate with them will die with me, and then they will be reduced, entirely and fully, to junk. Like most of us, I own some things that are beautiful enough that I can imagine someone who never knew or cared about me wanting to take them home and look at them. But for my magnets? Not so much.

We’ve all seen how the now-meaningless Fridge Magnets of the Recently Dead clutter estate sales, thrift stores, the Goodwill boxes. Almost all of us will eventually become as ephemeral as William Zimmerman, the Father of the Fridge Magnet who I described in my first post. We’ll be imperfectly remembered if we are remembered at all by a few stray postings on the Internet, snatches of hard-to-access memories. Zimmerman at least left his fridge magnets behind, the ones that he created (which is better than most of us), but I don’t really know anything about him. All I have of him is a few photographs, a few news articles. He is both forgotten and not-forgotten, a man who has been imperfectly archived.

Still, perhaps, Stewart is only partially right, about the futility of trying to preserve ourselves by means of magnetized plastic octopi with place names written on them. Perhaps someone could (if they were, for some bizarre reason, so inclined) try to recreate me from my magnets, guess at what I was thinking about, or why I bought them. They are, in a weird and plasticine way, a sort of language of memory, a personal history told in crap.

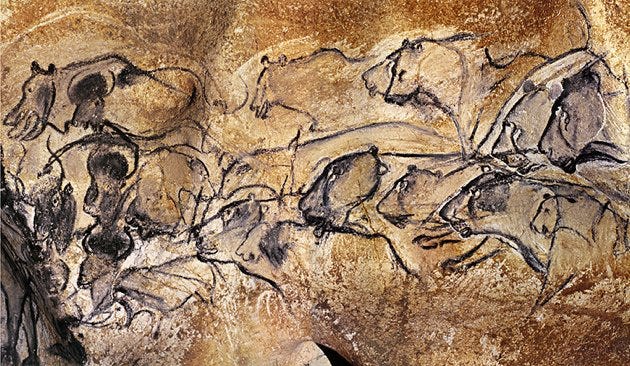

My fridge magnets, in this light, resemble the symbols that our earliest ancestor’s painted onto cave walls by firelight many eons ago. We have no idea what exactly they were thinking, what the specific texture of their thoughts was, but we know what images moved them, what they, themselves, wanted to be looking at.

Our fridge magnets are cheap plastic mnemonics, objects that operate on multiple levels: souvenir, gift, keepsake, remnant of ourselves and our geographic journeys. Souvenir-makers and sellers like them because they are cheap and self-contained and hard to break. They are a souvenir that you can pretend is somewhat practical: a way to transfer one’s adventures onto the mundane metal service of a household appliance you look at every single day.

They will, I expect and I hope, be with us – prompting our memories, amusing us mildly, offending high-class sensibilities – for as long as we exist, and as long as we have fridges to put them on.