I Answer Some Of Your Burning Drone Questions

Whenever drones pop up in the news, whenever they buzz unnervingly again into popular perception, people ask me what I think about these latest developments on social media. Most of the time, and regardless of the precipitating drone-related event in the news, they're about the same questions, revolving around people's understandable fears and concerns about drone surveillance intruding on their lives.

So, here's my quick-and-dirty attempt at a drone FAQ, which will do exactly what it says on the tin.

I will periodically update this document with new questions and information.

But first, here are some caveats:

This FAQ will largely concern United States drone law, as I'm an American citizen and most familiar with the regulatory system here. Other countries regulate drones in different ways.

I am not the Federal Aviation Administration, nor do I work for it. I am not a lawyer. And finally, I'm not Mr. Drones, Drone Magnate, Chief Executive of Global Drone Companies. I am a consumer drone pilot, drone data analyst, and drone tech consultant who's been working in and around the industry since 2013.

With that in mind, please don't complain to me if you're unhappy about how federal or state drone regulations currently work. As, again, I am not the Grand Vizier of Drones. Don't shoot the messenger.

Or, you know, the drone. More about that in a second.

The Beyond Visual Line of Sight Thing Sean Duffy Just Announced Isn't Actually New, or Particularly Scary.

On August 5th 2025, U.S. Transportation Secretary Sean P. Duffy, in typically alarming-sounding MAGA fashion, announced that the FAA had issued a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) that promised to "unleash American drone dominance" by permitting unmanned aerial vehicles to legally fly beyond visual line of sight.

Understandably, a lot of people are freaked out about this, because it's 2025 and one can usually safely assume that if a MAGA-appointed official is announcing something, it's going to be dumb, evil, or some combination therein.

I am here to tell you that you can, for the time being, chill out about the FAA's proposed rule for allowing drones to fly beyond visual line of sight.

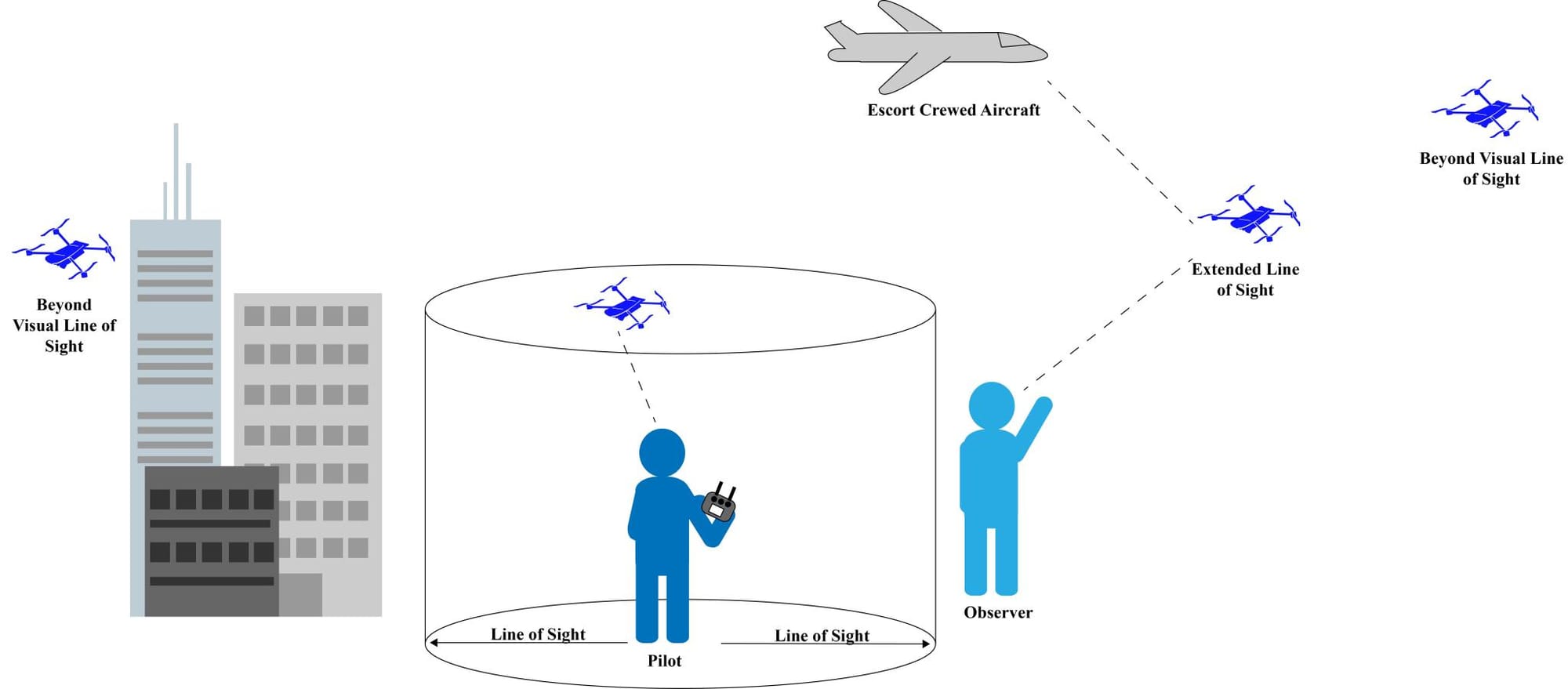

First, let's define what BVLOS means. "Beyond visual line of sight" is fairly self explanatory: it's what happens when a drone pilot or associated visual observer can't see the drone in the air.

Current regulations pertinent to small drone flights in the U.S, under 14 CFR Part 107, legally require that drones stay within this visual line of sight limit. This new rule proposes changing that under circumstances, for those who satisfy certain legal requirements.

Why do drone pilots and companies want to be able to do this? A lot of the demand revolves around drone delivery, which doesn't work very well without the legal ability to fly BVLOS - when you're delivering stuff with a drone, it's usually going to fly beyond where a human being can visually track it.

While I'm not a big drone delivery enthusiast myself - I continue to think it's largely overhyped - there are also a lot of other socially-beneficial use cases for BVLOS, like disaster response operations, scientific research, agriculture, and more.

Which brings me to the first reason I'm not losing a ton of sleep over this: regulators have been working towards a legal framework for permitting drone beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) flights for over a decade.

A lot of smart, reasonable people have been digging into this topic for a long time - indeed, this proposed rule was in the works well before Trump was elected for a second time, or even elected the first time. The U.S. government has been working on integrating small drones into national airspace since the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012, and both the FAA and NASA have been formally exploring how BVLOS operations fit into that picture for over a decade. In June 2016, the FAA issued Part 107 (14 CFR Part 107) which legally normalized the routine commercial operation of small drones within visual line of sight in U.S. airspace: when that rule was issued, the FAA's explicit goal was always to eventually release a complementary set of rules for BVLOS flights.

Back in May 2024, President Biden signed that year's FAA Reauthorization Act, which included a provision directing the FAA to issue a proposed BVLOS rule by September 16th, 2024. Obviously, the government didn't make that deadline - so Duffy is merely putting forward a rule that the Biden administration already explicitly directed the FAA to develop.

I am confident that, in the alternate universe in which Harris was elected in 2024, we'd have seen approximately the same NPRM announcement, just with less fart-brained language in the press release. (The actual proposed rule is titled "Normalizing Unmanned Aircraft Systems Beyond Visual Line of Sight Operations," which is far more normal sounding).

The second reason: Drones already can fly beyond visual line of sight, and they have been doing just that for years now in the United States, both legally and illegally.

The Part 107 rule, which has been in place since 2016, has always made it possible for drone operators to apply for special waivers that permit them to do otherwise-illegal things, like BVLOS flights.

You can review a full list of existing FAA waivers here, including numerous existing waivers for BVLOS operations. However, getting these BVLOS waivers is currently an extremely difficult and drawn-out process (although it has become somewhat less onerous in recent years). This new rule is an effort to standardize matters and speed up how review works.

Nothing about this recent BVLOS NPRM announcement changes drone's actual technical capabilities, either. Pretty much every drone on the market already has the capacity to fly well beyond visual line of sight, it just wasn't legal to do so before. (And unfortunately, it's really hard to catch pilots who are flying beyond visual line of sight, so we can rest assured that it's been happening pretty often).

And while this easier application process will likely be used by police and by delivery companies who want to legally fly drones beyond visual line of sight, the truth is that the FAA has been issuing lots of BVLOS waivers to American police departments and to delivery companies for years now.

If you have issues with how your local police and private companies use drones - and trust me, I almost certainly share those issues - you should take that up with your local government authorities. I absolutely agree that persistent drone operations carry with them a lot of security and privacy risks, risks that we don't fully understand.

We need to be pressuring our lawmakers to hold drone pilots, especially those in law enforcement and private industry, more responsible for ensuring that they are responsibly and minimally collecting potentially sensitive information while they're in the air. However, I also don't think that this NPRM is going to make a massive difference in that regard.

You need not push back against the overuse of drones alone, either: many regions and states now have advocacy groups dedicated to monitoring and fighting back against government over-use of surveillance technology.

The third reason: under this new rule, applicants who want to fly BVLOS will have to follow a pretty stringent set of legal requirements, which are described clearly in this fact sheet, and in more detail in the full text of the rule itself.

This isn't a free-for-all total-drone anarchy situation.

Among other requirements, BVLOS pilots will need FAA pre-approval for all areas where they intend to fly, which will require them to submit detailed information on the boundaries, number of daily flights, takeoff and landing areas, adequate communications coverage, and more. They will also need to present comprehensive security plans for devices, networks, and data, and there will be stricter rules for higher risk operations. This all seems pretty reasonable to me.

The fourth reason: This is still a proposed rule, not a final rule, and the final rule will likely take at least a year (or more) to come out.

We are still well within the public comment period for the BVLOS NPRM, so I strongly suggest you read the rule over and submit your concerns to the government yourself. I certainly plan on doing so.

What's more, it takes a long time for proposed rules to actually become law. As this Commercial UAV News article points out, it took 18 months for the Part 107 NPRM that was issued in February 2015 to actually become law in August 2016. While the U.S. federal government is currently a lot more chaotic now than it was back then, I still anticipate that this process is going to take a while.

Further information on BVLOS and the new rule:

The FAA's official BVLOS fact sheet for the August 2025 NPRM.

OIG Audit of FAA BVLOS Waivers from June 30th, 2025.

UAS BVLOS Aviation Rulemaking Committee report from the FAA, as published in 2022. This document explains some of the context behind the development of the proposed rule released in August 2025.

Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS): What is it and how can it advance NOAA’s science? - NOAA

BVLOS: The Future of Commercial Drone Operations [New for 2024] - UAV Coach

Experts react to FAA’s proposed BVLOS drone rule — game-changer or growing pains? - Dronegirl

Can I Shoot at a Drone If It's Creeping Me Out?

No, you can't legally shoot at a drone that flies over your property. Or a drone that's flying anywhere else, for that matter.

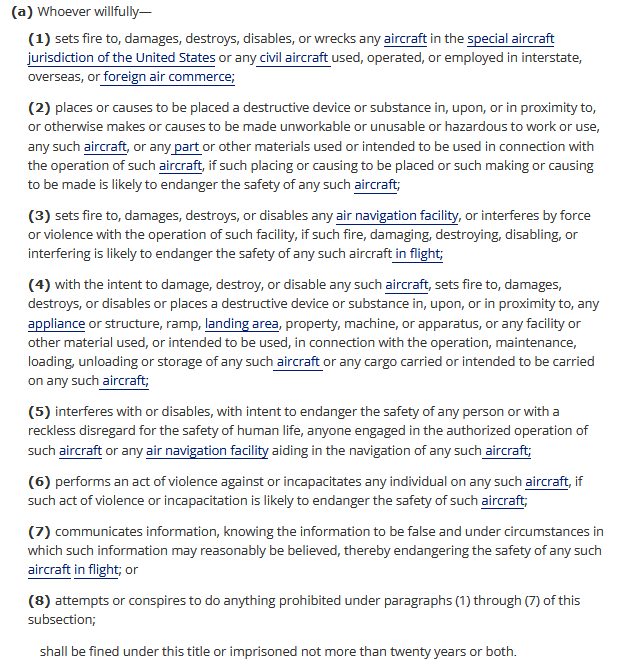

It is a federal crime to do so, as defined under 18 U.S. Code § 32, which pertain to the destruction of aircraft and aircraft facilities. The FAA legally considers drones to be aircraft, and has affirmed that this rule applies if you shoot one down.

You could also get in trouble, depending on your state and location, for criminal mischief and illegally discharging a firearm - as occurred in 2019, when a Long Island man shot down a drone that was looking for a lost dog. Some states also have their own laws explicitly banning discharging firearms at aircraft.

In this recent case, from December 2024, a Florida Man who shot a Wal-Mart delivery drone was "was charged with one count of shooting or throwing deadly missiles into dwellings, vessels or vehicles, one count of criminal mischief causing $1,000 or more in damage and one count of discharging a firearm in public or on residential property." He was ordered to pay Wal-Mart $5000 in restitution.

Further information on shooting down drones:

Why you shouldn’t try to shoot down a suspected drone - CNN

It Is A Federal Crime To Shoot Down A Drone, Says FAA - Popular Science

Are Domestic Drone Shoot-Downs Lawful? - Lawfare

To Shoot or Not to Shoot? The Legality of Downing a Drone - Dorsey + Whitney LLP

Can I legally try to take down a drone with a rock/butterfly net/spear/laser/other drone/trained falcon?

No, you cannot legally take down a drone in the air by any means.

There is no wacky loophole and no creatively-applied tool that will render you magically immune to established federal law about targeting aircraft in U.S. air space.

Let's review the text of 18 U.S. Code § 32 - Destruction of aircraft, which applies to drones as well as to manned aircraft:

As you can see, this law's text covers pretty much every possible base around "trying to destroy drones in the air."

Yes, this includes shooting at drones with lasers. Take it from my friend Phil, a well-known specialist in laser safety:

What could go wrong if I shoot at a drone, and the Feds don't catch me?

It's not only illegal to shoot at a drone, it's also dangerous.

For starters, people are notoriously terrible at accurately identifying the nature and location of flying objects.

I have heard a number of reports of people confronting drone pilots about flying over their property (which, again, is legal to do in most cases), when the visual and GPS evidence collected by the drone clearly demonstrates that the drone never crossed over their land at all. It is very hard in many cases to visually determine if a small drone has actually crossed your property line.

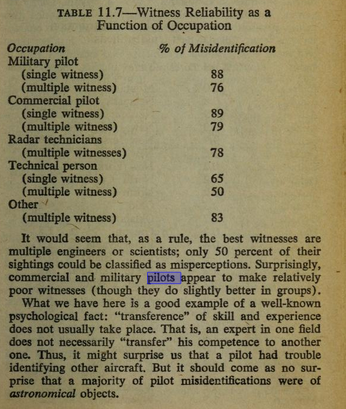

And while you might assume that specially-trained individuals are better at this than the average human, that may not be true. According to astronomer Allen Hynek's famous 1977 "UFO Report," professional pilots actually tend to be particularly bad at accurately identifying flying objects:

Even worse, this inherent deficit in human's ability to identify stuff in the air may lead you to believe that you're blasting away at a sinister drone over your property when you're actually shooting at something else entirely. Including, say, a manned aircraft with a human being inside of it.

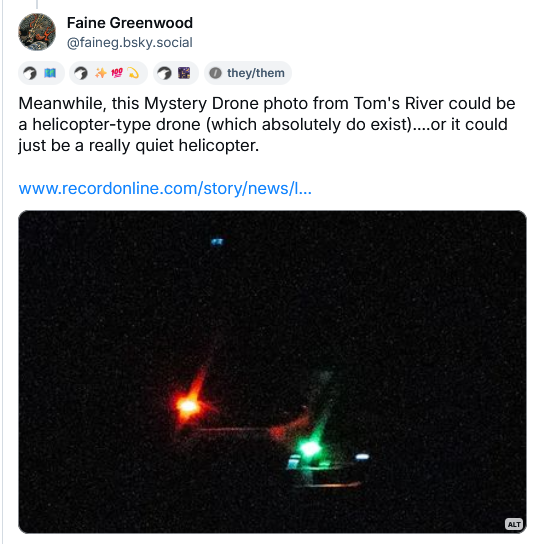

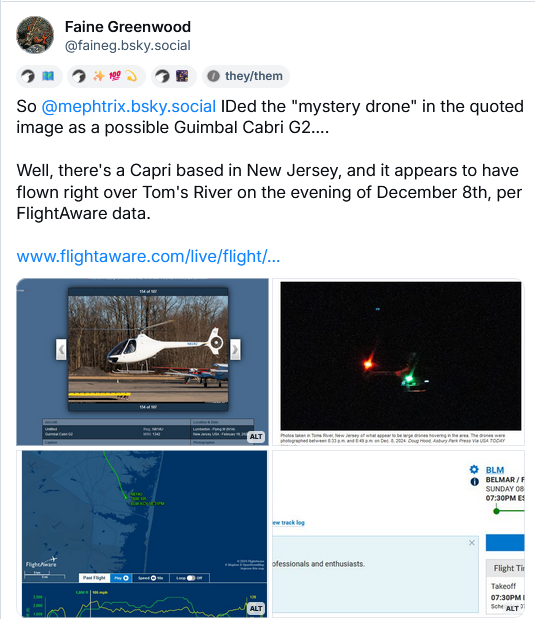

This reality about our species aerial ID capabilities was brought into stark relief during the December 2024 collective freakout in the U.S. over alleged "mystery drones." In almost all cases, the supposed "mystery drones" were found to be either bog-standard hobby drones, or manned aircraft doing normal manned aircraft things.

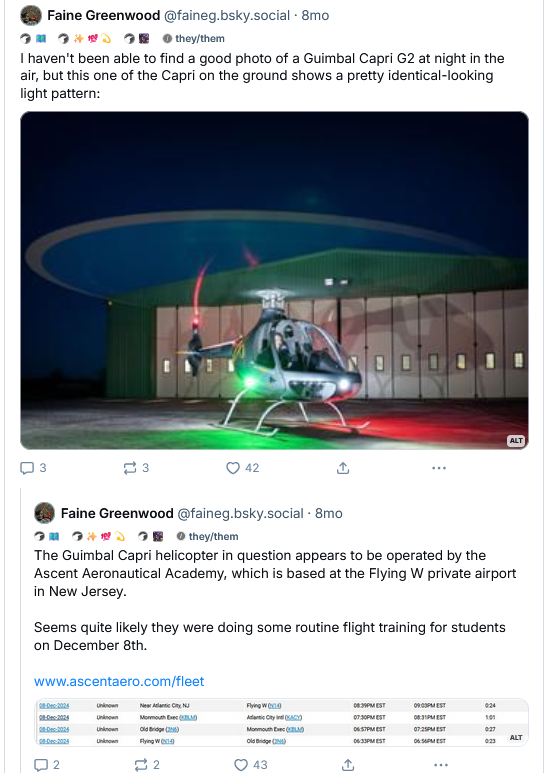

For example: during the peak of the mystery drone panic, New York's Times Herald-Record newspaper published a photo of an alleged "large drone," taken by an area resident. A friend of mine on Bluesky quickly identified the supposed "drone" as a manned Guimbal Cabri G2 helicopter - and I was able to match that aircraft up with a documented night-time training flight out of an aeronautical academy.

aaaaahhhhhhhhhh

I consider it to be a minor miracle that we made it out of the New Jersey Mystery Drone panic without someone in a manned aircraft being seriously injured or killed by some gibbering idiot with a shotgun. And I'm afraid that a similar panic is going to happen again in the future, with more deadly results.

What's more, people shooting at drones will inevitably be shooting into the air, and in most cases, they'll likely be shooting into the air in a populated area. The vast majority of sources that I've seen agree that it's pretty hard to shoot down a small drone, especially if you're not a Ukrainian soldier who's spent the last few years getting in a lot of drone target-shooting practice.

If you miss, your bullet has to come down somewhere - and as most everyone who works in emergency neurosurgery will tell you, that can result in devastating consequences for people on the ground.

Innocent people are killed on the holidays every year by so-called "celebratory gunfire" into the air, such as in this tragic event in January 2025 in which a 10 year old girl in Miami was struck in the head and killed by a stray bullet. Tragedies like this are why many states and municipalities in the U.S. have strict laws against discharging firearms in populated areas.

Shooting at a drone also puts the drone pilot at considerable risk. The pilot of the drone is likely a lot closer to you than you think they are.

A lot of people tend to assume that consumer drones have a much longer operating range than they actually do (which varies from case to case, but is usually in the ballpark of a mile or two). And legally speaking, a drone pilot in the US isn't supposed to be flying beyond "visual line of sight" in the vast majority of cases.

This means that there's probably a human being associated with the drone in very close quarters to where you're blasting away with your gun a an object in the air.

And this risk is not hypothetical. I have spoken with a number of licensed drone pilots who were flying their drones in legally-open areas, and who reported being shot at at terrifyingly close range with 12 gauge ammunition.

This is also why drone pilots, including myself, are really not keen on measures that would make their location on the ground (in addition to the location of the drone) visible to the general public through a widely-accessible app: we are genuinely afraid this could lead to legally-operating drone pilots being murdered. If you don't believe me, consider this recent case where a man was arrested for attempted murder after he opened fire on a drone pilot in California's San Gabriel mountains.

So, to reiterate: shooting at a drone is a federal crime, it's possible you won't even be shooting at a drone at all, and if you miss, your falling bullets can kill the pilot, or even a totally uninvolved person who just happens to be in the area.

Personally, I don't think it's worth it.

If you're mad about a drone flying in your area, I suggest that you try to find the pilot - who again, is probably closer than you think they are - and talk to them about it first. If you're afraid to do that, you can call the police. But defaulting to firearms is not a smart, safe, or legal solution.

Further information on falling bullets and human failings when it comes to identifying flying stuff in the air:

UFO Identification Process - Skeptical Inquirer

Observers cannot accurately estimate the speed of an approaching object in flight - Vision Research

What goes up, must come down: The dangers of celebratory gunfire - Baylor College of Medicine

Stray bullet: An accidental killer during riot control - Surgical Neurology International

Past incidents show falling bullets can still kill or injure someone - South Bend Tribune

Can I Stop Drones From Flying Over My Private Property?

The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration affirms control over all navigable airspace, which is often interpreted as extending all the way down to a "blade of grass." This means that generally speaking, if you own property, you cannot demand that aircraft, including drones, avoid flying over it.

Once, over a hundred years ago, Americans were permitted to control the airspace above their property. And then the Wright Brother's figured out powered lighter-than-air flight, the aviation industry began to explode, and everyone figured out that a major problem was brewing.

In the aviation age, giving every single property-owner the right to ban all overflight of their property is simply unworkable: our modern aviation industry wouldn't be able to function if manned aircraft were forced to constantly divert over vast numbers of privately-held areas. (As someone who flies across the U.S. pretty frequently, I, for one am grateful for this).

Over the course of the 20th century, by means of the 1946 Causby Supreme Court decision and the 1958 Federal Aviation Act (among other legislative and legal events), the federal government's control over U.S. airspace was more strongly solidified. Drones, of course, have complicated this status quo further since they first became broadly popular in the 2010s, as they have greatly reduced the barrier to entry to "flying stuff over people's property."

It's possible that the rules around drones and private property will change at some point in the future, as society's views of drones and their appropriate uses changes, and as technology makes it somewhat more feasible for both property owners and pilots to communicate boundaries to one another. For now, though, the FAA has declined to treat drones differently than they do manned aircraft.

That means that drones are, as a general rule, legally allowed to fly over private property as long as they are otherwise following the law. (And again - don't yell at me about this, as I am not the FAA).

Although the FAA claims final legal supremacy over American airspace, some states, towns, and municipalities do have more detailed laws concerning drone overflight, privacy, and private property. You should consult your local regulations for more detail.

Further information on drone overflight and private property rights:

List of relevant state laws regarding drone overflight and privacy - Drone Pilot Ground School

Property owners and suspicious drone activity: what laws apply? - Farm Office, Ohio State University Extension

Drone Regulation, Privacy and Property Rights - Drones and Aerial Observation, New America, 2015

What can I do if a drone is harassing me on my property?

First, consult your local regulations. While the FAA doesn't regulate privacy matters surrounding drones, some states and communities (like California and Texas) do have more defined rules about drone harassment and privacy issues.

If you think a drone is harassing you, or is generally being flown in an unsafe way that poses an immediate threat to people or property, it's worth reporting the problem to local police, even though I can't guarantee they'll do anything about it.

Drones in the U.S. are legally required to emit a remote ID number - a sort of digital license plate - that law enforcement can use to track down the operator. Private individuals also can collect these remote ID numbers in some cases, as occurred in this example in which a woman in Georgia successfully won an aerial harassment case against a drone operator.

Finally, you can (and should) report drone harassment to the FAA if you believe the pilot is violating the federal laws defined in 14 CFR Part 107. For example, it's a breach of the law to operate a drone directly over a human being without satisfying certain conditions.

Further information on drone harassment and the law:

Understanding Your Authority: Handling Sightings and Reports

What Can Police Do About Rogue Drones? FAA LEAP’s Role in Supporting Law Enforcement - DroneLife

Can I legally jam a drone's signal?

When I tell people that it's a federal crime to shoot at or otherwise physically take down a drone, they often respond with what they think is a brilliant workaround: jamming the drones' signal instead.

Sorry, folks. Jamming a drone's signal isn't One Weird Trick for shutting down unwanted drones in your area without resorting to illegal gunfire.

In fact, it's also a federal crime, and not one of your minor ones, either.

According to the Department of Homeland Security, a private citizen or organization who attempts to jam, spoof, or hack a drone is almost certainly violating a number of federal laws.

Per official DHS guidance, these laws could very well include the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (18 U.S.C. § 103), Interference with the Operation of a Satellite (18 U.S.C. § 1367), Communication Lines, Stations, or Systems, (18 U.S.C. § 1362), the Aircraft Sabotage Act, (18 U.S.C. § 32(a)), and the Aircraft Piracy Act (49 U.S.C. § 4650).

Personally, that's way more federal laws with serious teeth than I'm comfortable breaking.

The federal government takes a very hard line on "private individuals messing around with signal jamming" because the unauthorized use of these devices can lead to a host of very serious unintended consequences. These consequences include seriously pissing off your neighbors by taking down their Wifi and cell service, destroying the ability for public safety professionals to communicate with each other during emergencies, and compromising critical aircraft tracking systems at major international airports.

While you can certainly find a disturbingly large number of individuals and entities selling drone jamming technology on the Internet, it is illegal, per the FCC, "to advertise, sell, distribute, import, or otherwise market jamming devices to consumers in the United States."

The FCC also notes, in big bold unambiguous text, that the "use or marketing of a jammer in the United States may subject you to substantial monetary penalties, seizure of the unlawful equipment, and criminal sanctions including imprisonment."

Indeed, the government has historically taken the subject of unauthorized signal jamming so deadly seriously that only a small number of federal agencies - Defense, Justice, Homeland Security, and Energy - are permitted to take any measures whatsoever to interfere with drone flight in any way.

These drone-mitigation moves are strictly controlled, and are largely restricted to drones that are deemed a credible threat to certain facilities or assets. Local and state police are largely legally barred from taking any drone mitigation steps at all.

In the wake of the late 2024 "mystery drone" panic, the federal government has seen a recent Trump-driven push to expand government's legal ability to use counter drone tools, and to loosen up existing legal restrictions on state and local authorities ability to take down or otherwise counter drones in the air.

As things stand, if you are part of an organization or governmental entity that is interested in purchasing technology for drone detection or mitigation, you absolutely should consult a specialist lawyer before signing any contracts.

If you are a private individual who just thinks drones are annoying and would like to mess around with jamming them like all those cool soldiers in Ukraine you see on social media: don't do it, dumbass.

Further information about legal issues with counter-drone technology:

Jammer Enforcement Information - Federal Communications Commission

Federal law enforcement officials make the case for expanded drone authorities - FedScoop

Radio Frequency Interference Best Practices Guidebook - CISA

Information About GPS Jamming - GPS.gov

RESTORING AMERICAN AIRSPACE SOVEREIGNTY - Trump Executive Order, June 2025

Can we train birds of prey to take down drones?

Way back in 2016, a group of Dutch police decided to experiment with training sea eagles to take down errant drones. A gazillion publications promptly picked up the story, and now I anticipate that I'll be having to field "But What About Counter-Drone Eagles, Eh, Smart Guy?" questions until I die.

Sorry to disappoint, but most every effort to use birds of prey to take down drones has proven to be a miserable failure.

The massively-viral Dutch effort to train eagles to take down drones crapped out after a year of experimentation, after the cops realized one fundamental truth about eagles: they are not purpose-bred German Shepherds, and it is very hard to get them to do stuff on command.

According to Dutch falconers quoted in the Netherlands Times, the people behind the program apparently never bothered to consult with them on the feasibility of the counter-drone eagle schemes.

Experts pointed out that drones can pose a serious safety risk to the birds, raising serious ethical issues conscripting innocent, non-domesticated birds to deal with an entirely human-created set of surveillance tech problems. Experts also pointed out that eagles are really big, prone to frustration, and could very well redirect to somebody else in the vicinity, with talons "so strong that it can easily pierce a child's head."

Despite the failure of Netherland's grand experiment in bird-based counter drone techniques, authorities in Switzerland tried the same thing, ultimately shuttering their own program in 2022 due to concerns about animal welfare and practicality. (The eagles were apparently never employed on an actual mission).

A French Air Force attempt to train golden eagles to take down drones appears to have been quietly shuttered in 2018 after one of their not-so-biddable raptors swooped down upon a five-year-old girl who'd been innocently enjoying a family picnic, clawing her in the back.

An investigator speculated to the Daily Mail that the eagle might have mistaken the child, who was wearing white, for a drone. Which does not inspire massive confidence in the aircraft-identification skills of eagles.

While Indian security authorities appear to be continuing to experiment with using trained eagles to combat drones as of early 2025, I can't say I'm optimistic about their long-term odds of success. And toddlers wearing white on the ground in the Hyderabad area best be watching their backs.

Yes, wild birds sometimes will attack drones (sometimes in extremely funny ways). But this behavior isn't exactly predictable, and it's also, as mentioned above, dangerous for the bird. This is why institutions that host established bird of prey nesting sites, like the U.C. Berkeley campus, ban drone flights anywhere in the general vicinity. These drone flights are seriously stressful for nesting birds, and place them at risk of injury.

Some falconers do use drones to train their birds, as I discussed in this 2015 Slate piece. But they also place special emphasis on ensuring that the birds don't get close enough to the drones to get injured.

Further information on birds and drones:

A meta-analysis of the impact of drones on birds - ESA Journals

Flying Drones Pose Danger to Threatened Birds - Audubon

Is there a way to identify drones in the air, by means of some kind of digital license plate system?

Yes, there is.

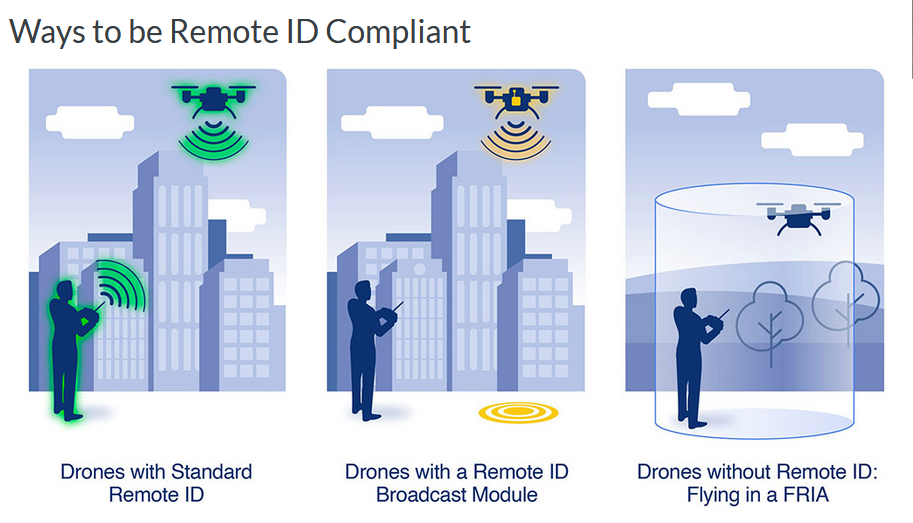

Since early 2024, the U.S. federal government has legally mandated that essentially all drones comply with the new rule on Remote ID, which requires that they 1. be registered with the federal government and 2. emit a broadcast signal that provides identification and location information (among other information) when in flight.

Drone manufacturers have known this was coming since at least 2019, and most drones sold by major companies in the U.S. today ship with hardware that complies with the remote ID rules (or at least, they say they do). Both recreational and Part 107-licensed drone pilots can also retrofit existing or custom-built drones with remote ID modules as well.

While there's a lot of complexity and controversy surrounding this move, the key thing you should know about it as a normal non-drone-nerd person is that remote ID functions pretty much like a digital license plate.

The drone emits a signal that the FAA, law enforcement, and other authorized parties can use to look up who the drone belongs to, and to locate the pilot on the ground (among other functions). This allows authorities to more readily identify rule-breakers, like this Reddit user who flew above the legal altitude limit of 400 feet.

However, these remote ID signals can only can be picked up at relatively short range - reliably at about a mile in distance, and much more infrequently at 10 miles, per this interesting new study from the FAA's ASSURE Center of Excellence for UAS Research.

Theoretically, members of the public can also use this "license plate" number to alert authorities to drone pilots who are breaking the rules. In practice, while there are mobile apps that profess to show you the remote ID of drones flying in your area, in my experience and that of others, they mostly suck.

Smartphones just don't seem to be great at picking up on the relatively short-range signals that drone remote ID modules emit. It is possible to buy specialized receivers that are much more capable of picking up on these signals, but most people are, understandably, not going to do that.

We're also seeing some major, ongoing issues with getting both law enforcement and the general public to recognize that the Remote ID system exists, much less convincing them to actually use it to track down suspicious drones, as is highlighted in this blog post from drone command and control accessory maker uAvionix.

I agree with them that Remote ID technology could have helped dispel some of the public anxiety around drone flights in New Jersey during the Great Drone Freakout of 2024 - but it appears that both local cops and sky-scanning citizens were largely unaware it was an option.

I hope that the federal government recognizes these problems and figures out how to improve upon the current shortcomings of the drone remote ID system.

We absolutely do need a more user-friendly mechanism for letting people on the ground figure out who's flying drones above them and for what reason. The goal is to implement this in a way, like license plates, that is legible to law enforcement while also providing drone pilots with a measure of privacy and security.

And yes, us drone pilots don't want our location on the ground, in addition to the location of the drone in the air, to be readily available to the general public for good reason - since as mentioned above, a LOT of people seem to want to shoot at us at close range, even if we're following the law.

However, much as I'd like to see some sensible changes made to how we're implementing remote ID that make it easier for the public to figure out what's going on with drones in their area, it's 2025. I am not exactly filled with confidence in the current occupant of the Oval Office. We'll see.

Further information on remote ID for drones:

FAA guidance on remote identification of drones

Part 89- Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft Rule (full text)

Three Take-Aways From the FAA’s Assure A50 sUAS Traffic Analysis Study - Dronelife