I Just Want a Cute Robot Lamp That Isn't Evil

Apple's engineers have figured out how to design a robot lamp so adorable that everyone I've shown the video to says they'd die for it.

By studying how to translate human expression into the movements of an outwardly-normal looking appliance, Apple's team have turned the winsome hopping lamp from the title screen of Pixar movies into an actual object. With its little light bulb face, the Apple ELEGNT is a household appliance that looks to a human interlocutor for further instructions just like a friendly dog would. It expresses both joy and sorrow when you chit-chat with it about your day. It gently nudges a glass of water towards you when it thinks you could use a drink.

I don't know if Apple is actually going to sell these. But if they do, they'll likely sell millions of them. Including to me.

And yet, as I watched that video and found myself seized with my own desperate desire for a little lamp pet to call my own, I had to remind myself of a central modern truth, as I always do whenever I find myself beguiled by a new piece of technology:

Apple will find a way to make this thing, in one way or another, secretly evil.

I am not the only person who has learned that in the dark year 2025, we should be highly suspicious of any technological object that fills us with a sense of wonder and delight.

I think that this modern shift in how we think about cool new technology is a tragedy. I also think this is not good for the tech industry.

Sure: consumer products that are secretly evil, sold by sinister corporations that are aware that they’re evil, are nothing new. Asbestos. High fructose corn syrup. Cigarettes. Lawn darts. Leaded gasoline. The legendarily murderous Ford Pinto.

Still, I'd argue that until recently, it was generally agreed upon that those products were exceptions to the norm.

Not that long ago, American consumers largely did not operate under the assumption that every new gadget and appliance on the market concealed some hidden mechanism that might be used to exploit them, spy on them, or train large language models. And not that long ago, American consumers generally assumed that regulators would at least attempt to protect them from actively malignant products.

i was marinating in this stuff as a small child

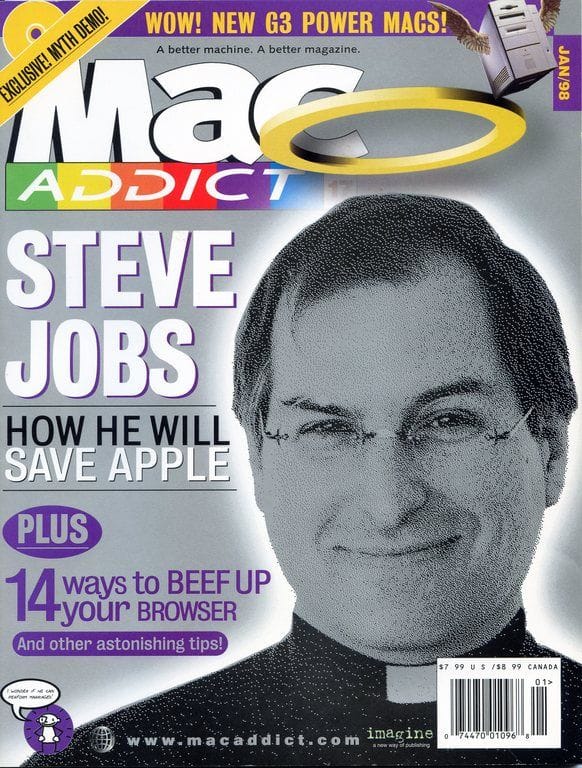

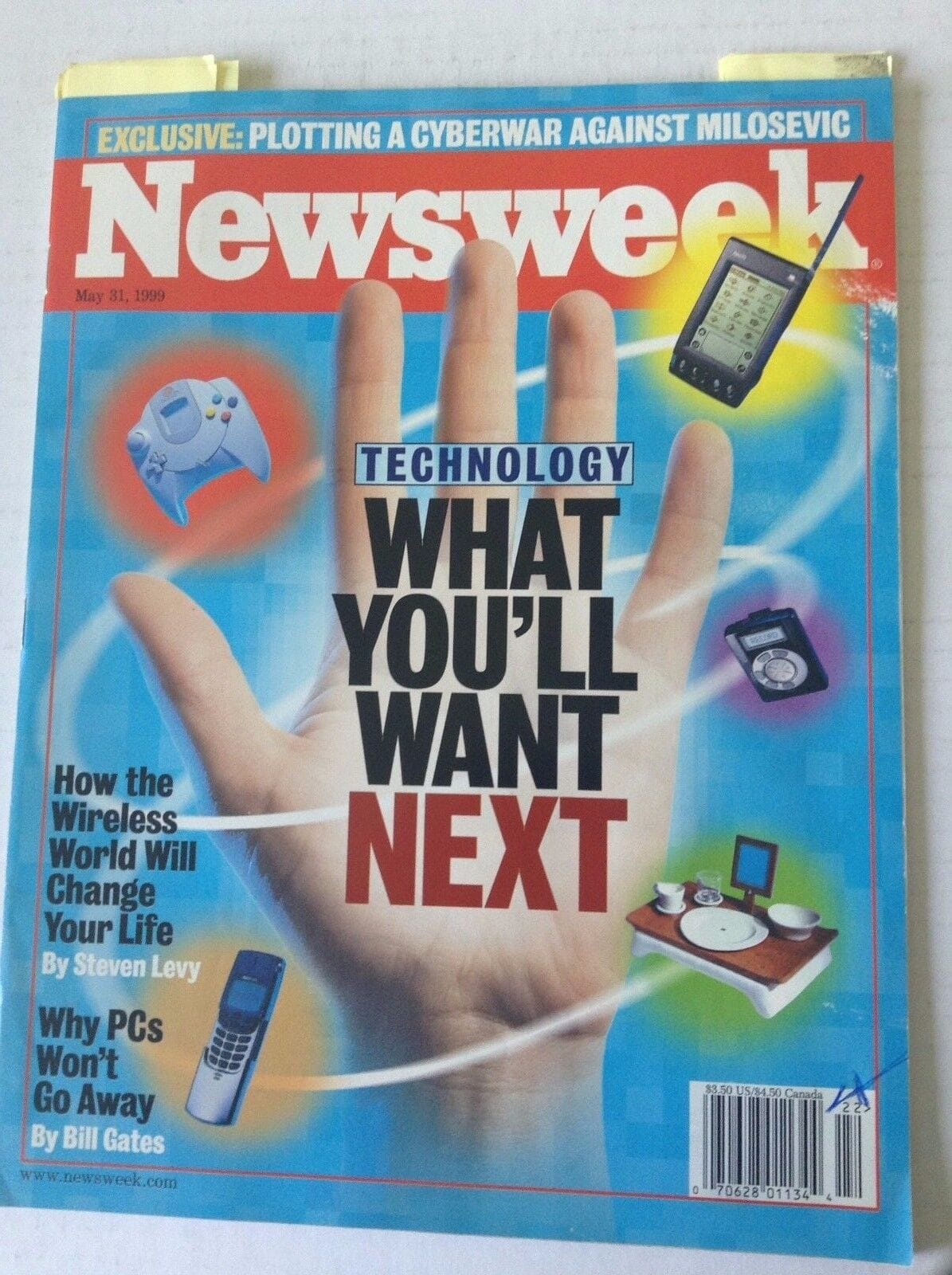

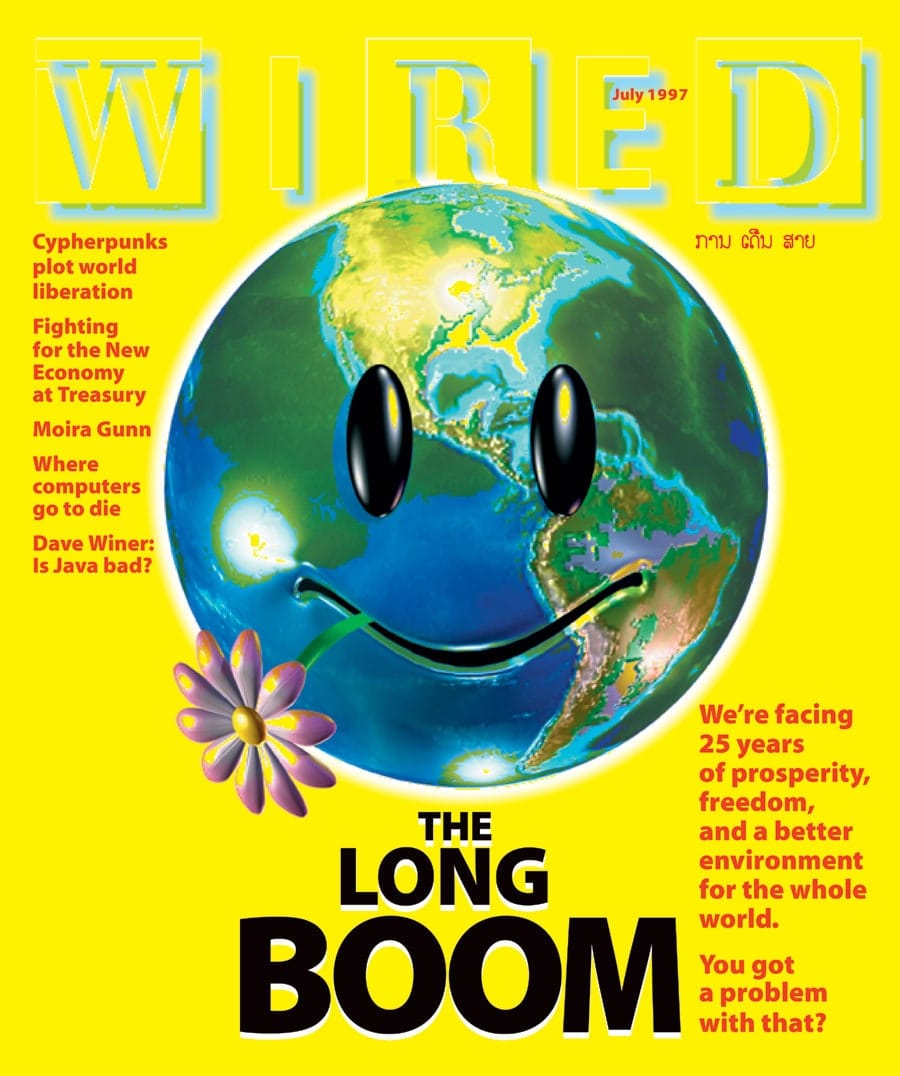

I know this because I used to be one of those people, way back in the mid-1990s when I was a dweeby elementary school kid who lived for Going on the Computer. I’d devour new and neon-colored issue of Wired and MacAddict and Newsweek and Discover, eager to read about how consumer tech and the Internet promised to swiftly become even cooler than they already were. I found it even more thrilling to be able to use the Internet to read about new innovations: it felt like technology was propagating itself, propelling me along with it.

Generally speaking, these mid-1990s publications promised Dumb Kid Me a tech-enhanced future of ever-more-intricate and realistic simulation video games (which were my favorite), mostly-positive interpersonal connection between people many miles apart, and a bonanza of digital creative expression paired with interesting new careers. When I got my first Bondi Blue iMac, I regarded it as something of a whimsical friend, a pal that accompanied me on my first forays into trolling people on Internet pet forums and reading terrible anime fan-fiction. At no time did I assume that Steve Jobs was using it to develop a sinister psychological profile of my 5th-grader brain. The iMac was just an iMac. It did what it said on the tin.

This was a perfectly reasonable expectation for me to have about technology. In the decades since, like so many people, I’ve lost it.

Consider the example of The Sims, the legendarily weird life-simulation game that was first released by Maxis early in the year 2000, when I was 11. My parents bought me the game for Christmas that year, which came on a CD, which I popped into the aforementioned iMac whenever I wanted to play it. Like so many other people my age, I then spent approximately 2 million wholesome hours meddling cruelly with the lives of my tiny computer people.

I did purchase a few of the expansion packs over time, including the one which, weirdly enough, included a tiny computer simulcra of Drew Carey who'd show up at your Sims parties. Still, the base game was plenty fun on its own, and I could play it whenever the perverse urge to trap a virtual middle-aged man in a ladderless swimming pool struck me.

Now, when we purchase a product, the product also (in a sense) purchases us.

Today, far more terms and conditions apply to playing The Sims than they did when you were able to buy the game in an actual cardboard box at CompUSA.

In 2025, while the barebones base Sims 4 game is free to play, you need an Internet connection to play the game all. To download and to run it, you also must download Electronic Art's own Origin gaming platform, which was revealed, in 2019, to have a glaring security vulnerability that left millions of user's data exposed.

At the moment, an attorney firm is investigating current Sims owner Electronic Arts for privacy violations, alleging that the company illegally tracked the information of those who played its mobile The Sims:FreePlay spinoff. And while you may not technically need to spend money to play The Sims 4 in 2025, Electronic Arts has released 18 (and counting) paid expansion packs for the game, accompanied by an even more massive number of paid downloadable content packs. If you were to purchase all of this additional content - which a lot of people assuredly do over time - you'd end up spending $1,929 just to torment some virtual people, according to a recent estimate.

These changes surrounding a product as long-running as The Sims is what I have come to think of as Evil Technological Creep in action, propagating over time.

new furby and old furby and honestly i'm impressed at how much more upsetting the new one is

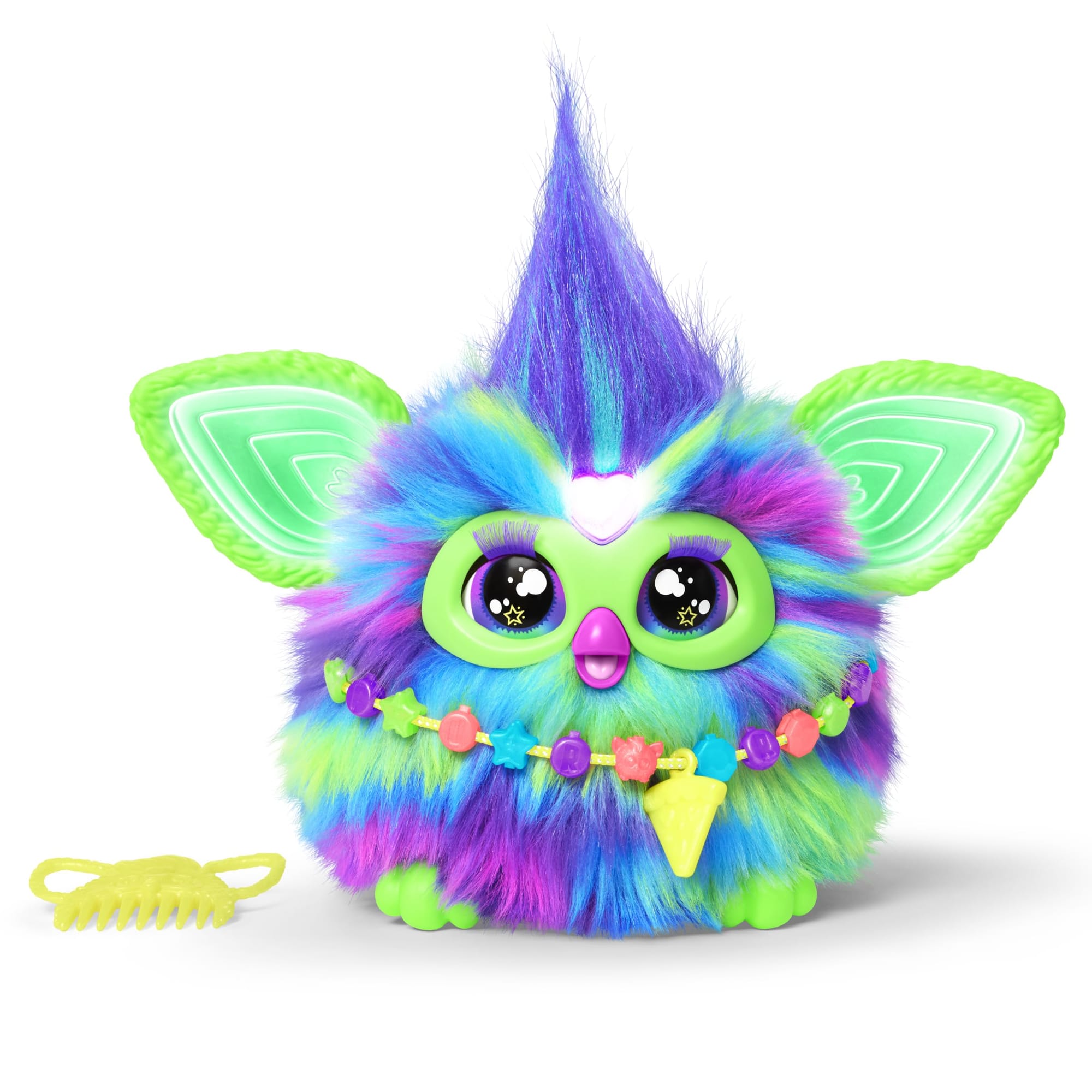

For another example, let us pause to stare into the unblinking plastic eyes of the Furby, a line of interactive robotic pets that spoke in eerie tongues and which were wildly popular for a brief period in the late 1990s.

Furbys were pre-programmed to appear as if they were becoming better at speaking English over time as they interacted with a human owner, and they could use their internal sensors to interact with other Furbys nearby, as if they were part of an especially irritating flock of artificial robotic birds.

While the toys contained no recording or sound interpretation devices, their ability to mechanically emote gave them a creepily convincing veneer of sentience - a veneer of sentience so convincing that for a brief period, they were actively investigated and banned by the federal government of the United States. Authorities banned Furbys from the premises of the NSA and the Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth, and the FAA required that people take the batteries out of their Furbys on airplanes. (Government documents about the great Furby Panic of 1999 were recently released to the public via FOIA, and you can read them on the Internet Archive).

Paranoia over the prospect of Furbys containing some form of secret and insidious intelligence spread to the general public, as hospital official worried that they’d electronically jam medical equipment, and angry parents accused the little technicolored robots of teaching their children to say “fuck.”

The Furby Panic was all a big misconception, an embarrassing collective freakout based on nothing more than paranoia and a lack of familiarity with electronics. And yet, as I read through the NSA’s old documents regarding their internal fears about the creeping Furby menace to America’s state secrets, I was struck by how, in 2025, many of these concerns about innocuous-seeming consumer electronics doubling as sinister spy tools have actually come to pass.

In 2018, users of the Strava fitness app really did inadvertently reveal the location of secret US army bases. And while the original Furbies of the late 1990s weren't actually capable of spying on innocent children, researchers really did find disturbing security vulnerabilities lurking within 2017's new Furby Connect model.

Perhaps the people freaking out over Furbys back in 1999 were correct to do so, but were just a few decades too early, anticipating the trajectory that both the electronic toy industry and the world at large had already begun to trundle its way towards.

And I also have to wonder about this: if both government officials and regular people were so horrified by the mere prospect of Furbys spying on them back then, how did we allow ourselves to get to a place today where our consumer electronics really are insidiously snooping on our private lives?

How do they spy on us? Let me count the ways:

Literally everything that involves your smartphone, the most iconic and most indispensable creeper-machine of them all (now with added AI tools that want to take your job!). Grotesquely poorly-secured Ring security cameras allowing creeper employees to spy on customers in their bedrooms. Air fryers that quietly send data on your food-crisping habits to trackers operated by Facebook and TikTok. Children's music players branded with Peppa Pig that aggregate behavioral data on play habits. Baby monitors that hackers can use to issue kidnapping threats, Roomba robotic vacuums that quietly map user’s homes, and washing machines that, for some reason, want to know your date of birth and your phone number. There are even security vulnerabilities that make it possible for miscreants to break into pacemakers, paving the way for the most dystopian possible form of online blackmail.

There’s also the incessant drumbeat of oops-I-did-it-again data breaches involving fitness trackers, like this nasty 2021 specimen from Fitbit and Apple. And perhaps most damning of all, there are various secret and unabashedly evil features that are shipped with every Tesla car produced by Elon Musk's odious company - as demonstrated by a recent lawsuit claiming that the company deliberately speeds up the odometers on its vehicles to ensure they fall out of warranty faster.

I could keep running through this grim list of examples of Evil Creep all day, but I imagine you're picking up on the pattern.

Which brings me back to Apple’s adorably emotive lamp.

Today, you can have that adorable interactive lamp. But as it sits there on your desk beguiling you with its whimsical ways, you will also have to live with the knowledge that it's most likely harvesting data about you for a shadowy corporate overlord in the process.

Today, if you invite Lampy into your home (I hope you’re better at naming lamps than I am), you'll also have to accept the risk that years down the line, the data your adorable lamp collected about you will be compromised by some hacker creep in a basement in Moscow, sold off to the highest bidder who will do God knows what with it, and no one will ever apologize to you about it.

As I write this in 2025, huge swaths of humanity have been conditioned to expect that if we want to purchase a neat new consumer product or play a fun new video game, we must accept that a corporation will take our purchase as consent to use that product to snoop into our private lives for their own financial gain, in such a way that that sensitive information about us can then be easily stolen and exploited.

Call it surveillance capitalism, digital colonialism, or data extractivism - there's a lot of terms to describe how impressively tormented our technological purchasing landscape has become, and a lot of people have written extensively on the subject. What it boils down to is that we've created a deeply perverse world in which consumers have come to assume that all cool new technological products are also Trojan horses containing a hidden complement of Greek soldiers wielding nasty pointy spears. Metaphorically speaking.

spiders georg

What's more, these practices have become so totally pervasive that it's almost impossible to avoid being subject to them. Even Spiders Georg, resplendent in his cave full of spiders, probably has a consumer profile or two knocking around in the equally dark and spider-filled recesses of Meta's servers.

Faced with what seem like insurmountable obstacles to protecting their privacy and their dignity, too many people seem to have become resigned to living in a world in which they must assume that new technological toys (like adorable lamps) are secretly evil. "It's bad, but it's not like they don't already have my data already," they say to themselves.

It's a form of learned helplessness that makes me terribly sad.

And while I find this attitude deeply depressing, it’s not like I can blame them. American consumers have, from bitter experience, learned to expect that regulators will simply sit aside and let these invasions of their privacy and their trust happen. We’re faced with a constant stream of cases in which corporations are caught doing suspicious and evil things with our data, and then either go unpunished or are issued a slap on the wrist so delicate and baby-soft that it wouldn’t faze your average newborn kitten.

Indeed, at the moment, the world’s most egregious creeper, Elon Musk, is functioning essentially as the unelected Grand Vizier of America, having experienced zero meaningful regulatory consequences over many years of constant assaults on consumer trust. From the perspective of many normal Americans, Evil Creep in tech has simply become a grim but unchangeable fact of life, as inevitable as the tides.

That’s some bleak shit.

Dark and filled with demons as the current situation is, I do see a few signs of resistance to Evil Creep beginning to take form, out there on the horizon. According to survey data, American trust in big technology companies has tanked in recent years, even more so than trust for institutions in general has.

No wonder the public is increasingly refusing to take the bait when it comes to Big Tech's desperate and sweaty efforts to convince everybody to use their AI tools.

Per another recent tranche of survey data, people around the world trusted AI companies considerably less in 2024 than they did in 2019: it appears that after a few years of constant exposure to AI grifters, many people absolutely do not like what they're seeing. According to encouraging 2025 data from Edelman, just 32% of Americans claim to trust AI. It appears that AI promoters years of running around chortling about how their tech will put a bunch of people out of jobs is, in fact, making people hate them.

As a longtime skeptic of technology, I'm deeply heartened to see that people are starting to turn on the companies and institutions that have forced us to assume that adorable lamps are evil.

And yet, the fact that we've arrived at this place of entirely-deserved distrust of technology also saddens me.

While I spend a lot of time talking shit about technology and the loathsome men that are its most public representatives today, within me beats the secret and constantly-disappointed heart of a techno-optimist.

I've been fascinated by the promise of technology since I was an elementary school kid flipping through Wired, dreaming about the wacky futuristic shit that I'd see in my lifetime. I've devoted my career to novel technology: the core, fundamental reason why I work with civilian drone technology for a living is because I think it's cool as hell, because I remain totally fascinated with how humanity figured out how to make tiny flying camera robots that hover in the air like weird artifical bugs.

In truth, my life-long love of technology is exactly why I've spent my adult life yelling about how it can be used for evil. I believe that there are good uses for many modern innovations - and yes, that includes AI - and that we are being systematically denied many of these benefits due to the horrible actions of a pack of greed-addled dead-eyed oligarchs. I am constantly filled with both rage and sadness over how we've collectively allowed the promise and wonder of new technology to be perverted by a small contingent of miserable assholes.

I want a future where an adorable robotic lamp is just an adorable robotic lamp. Disappointed optimist that I am, I still believe we can get there.