Newsletter: Drones in Helene, Bad GOP Conspiracy Theories, and The Religion of Technology

It's officially fall in the Boston area, which I both enjoy on its own merits and also dread as it presages the arrival of winter. In any case, I'll be spending part of this month in the UK, where I'm traveling for a conference. I've decided to stay over a few more days in London, and then I'll head to Portsmouth to spend a few days looking at old ships. I try to live my life by a rule of Never Pass Up A Chance to Look at a Really Old Boat.

Anyway.

Oh, Great, GOP Conspiracy Theories About a Routine Request to Avoid Flying Drones Over Disasters

Hurricane Helene has flooded out a bunch of places I'm familiar with, as someone originally from the South with family in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky. As is now typical during American disasters of all stripes, disaster responders are arriving on the scene with a whole lot of drones. People are using them for search and rescue, damage assessment, media stories, and even, in one case that's been splashed across the media, and even to deliver insulin. It's a list of disaster response drone use cases that I've seen repeated over and over since federal drone regulations eased up back in 2016, and I think that's a wonderful thing.

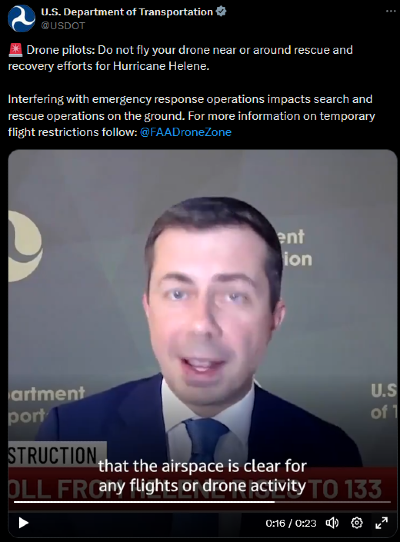

As is also typical with modern disasters, many people who own drones but aren't affiliated with official disaster response efforts are also flying over the vast swaths of destruction left behind by Helene. This prompted U.S Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg to post a Twitter video imploring people to stop flying their dang drones in the vicinity of rescue and recovery efforts.

This was an entirely reasonable and logical request. Airspace management over disasters is an absolute nightmare in general, and small drones - which have only very, very recently been integrated into the national airspace management system with Remote ID - complicate that process even further.

Aircraft with humans on board, like the helicopters that are currently bringing essential supplies to stranded people in North Carolina, really don't want to put themselves and others at risk of crashing and burning after an inadvertent collision with an unexpected small drone - regardless of the good intentions of the drone pilot.

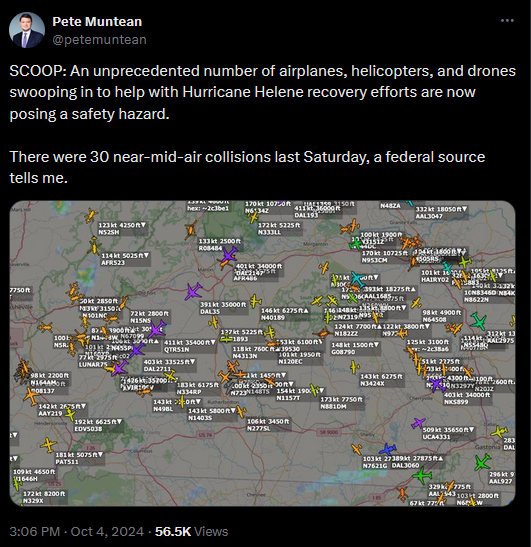

Lest you think both me and Mayor Pete are overreacting a bit here, CNN journalist Pete Muntean just posted this on Twitter, noting that a federal source said there were "30 near-mid-air collisions last Saturday" over Helene recovery efforts:

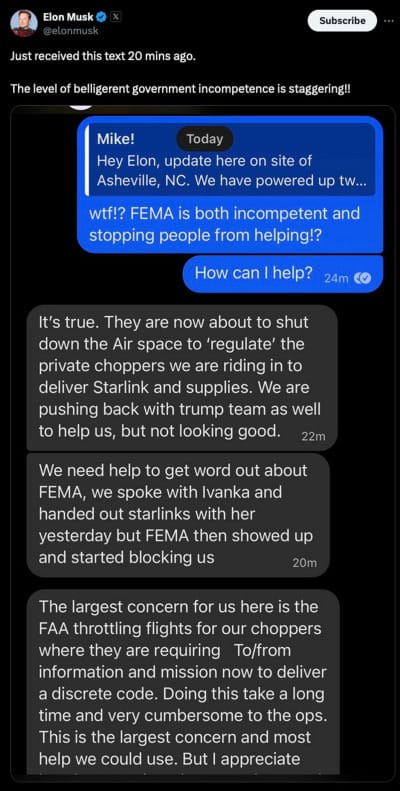

As I write this at 4:10 EST, I've been forced to update this newsletter again because Elon Musk has decided to apply his Ketamine-addled moist sponge of a brain to exposing the government's devious plot to prevent fatal air crashes.

Needless to say, this is wildly dangerous.

And the FAA does have a mechanism that drone pilots can use to quickly get permission to fly over restricted areas during emergencies (which lots of people I know use on a regular basis). I believe that knowing that this mechanism exists should be a bare-minimum requirement for anyone who wants to fly a drone over a disaster area that's being used by other aircraft in the first place.

Unsurprisingly, because Elon Musk's Twitter is a portal opening directly into hell, a bunch of weasel-brained idiots who have never devoted a single neuron to airspace management during disasters before replied to Buttigieg in intensely stupid ways, claiming that private drones have been "saving lives for days," and that the government is "hiding something."

This is the usual nonsense that comes up whenever the government decides to restrict airspace over disaster areas to authorized users.

In any reasonable timeline, in any reasonable country, it'd be ignored.

But we live in the MAGA-poisoned world of 2024, right before a horrifically pivotal election, and Donald Trump has been running around falsely accusing the government of failing to meaningfully assist with Hurricane Helene recovery efforts in any meaningful way. Which means that the likes of the New York Post decided to run a story highlighting random idiots comments on Buttigieg's utterly routine request that non-authorized drones stay out of occupied airspace, as if they had any more value than the far-off fart of a dozing baboon.

This rhetoric, along with all the other insane filth that the GOP is currently spewing about the supposedly evil intentions of government employees who are out there trying to do their best - with depleted funding that can be directly attributed to the GOP's congressional goons themselves - is going to get disaster responders killed if it continues.

Drones Are Living Up To Their Promise, Though!

I'm currently working on a project dedicated to developing better best practices for drone data collection during disaster, and well, all of this is a good reminder that this work is nothing if not relevant.

I was also reminded again about how drones are something like the opposite of the current LLM and AI boom.

They're ultimately consumer tech hardware that has largely lived up to the hype. While dingleberry venture capitalists did spend a few fetid years in the 2010s desperately trying to convince Americans that they all needed a tiny pocket drone to shoot video of the tops of their heads (anyone remember the Lily drone debacle?), most eventually gave up and shuffled off to greener pastures in NFTs and, a few months later, AI.

Meanwhile, people around the world looked at inexpensive flying cameras, thought "I could do something with that," and proceeded to get to it. It's this creativity that has kept me interested in drones for so long: human beings have a near-endless capacity for figuring out what to do with these things, from collecting whale-snot to projecting Galactus at full-size on the skies of ComicCon to finding buried land mines before they kill kids. Drones, as they say, are a land of contrasts.

i'm ambivalent about Marvel stuff but this is pretty sweet

Of course, it's true that not everyone owns a drone, or wants to own one. Which is perfectly acceptable.

As I mentioned above, the feral venture capitalist contingent have largely given up on consumer drones, and I'm pretty grateful for that. It's a state of affairs that's a far cry from the AI hype industry's current flop-sweat scented desperation to convince Americans that they need to spend money on chatbots that tell only lies. Civilian drone sellers don't need to resort to that degree of sales desperation nowadays: it's a drone, you can collect data and stuff with it. Buy one if that's what you want.

Indeed, I've heard legend and song of a time when the degree of specialist success enjoyed by the consumer drone industry used to be considered a very desirable outcome for a new consumer tech sector. At least, before the Unicorn Era convinced the LinkedIn power-user class that a new innovation is worthless if it can't be crammed down the throats of every American in every profession forever.

Yes, I know that "AI" (a term that has sadly been cheapened into sludge by hype-men) isn't useless. There are a number of useful things you can do with it - indeed, some of those things intersect very closely with what I do, like using automated image identification tools to do stuff like "figure out how many buildings have been destroyed after a flood by evaluating drone imagery."

But I suspect that AI is actually a lot more like drones with regards to its degree of mass consumer usefulness - and a lot less like say, a smartphone, an object that everyone actually does use every day - than Sam Altman wants you to believe.

Books

Recently, I read:

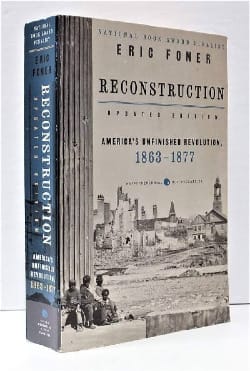

Eric Foner's "Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877," a doorstop-sized yet entirely readable account of the whole sorry business of reconstruction in the United States. This is the book that all my friends who actually study reconstruction suggest as a general overview of a topic that is typically skirted over or actively butchered in American lower-school history education. I am glad I read it: it is a very clear outline of how, for a very brief period in the wake of an earth-shakingly brutal war, the United States had a genuine chance to advance towards a more progressive future.

Black Americans served in Congress, progressive policies gained new attention, and social services and public education were introduced for the very first time in Southern states that had previously operated as essentially feudal plantation economies. And then, due to a combination of hideous violence from white Southerners who refused to see Black Americans as human, white Republican leaders craven lack of nerve, the white voting public's racism and general eagerness to Get Back to Normal, bad-luck economic misfortune, and Gilded Age-era corruption and economic inequality, most of these heartening developments crumbled into ash again.

A lot of it will feel very familiar to the 2024 watcher of American political affairs, in a way that is both deeply distressing and - certainly not comforting, but at least a reminder that we are not living in entirely unprecedented times.

Right now, one could argue that we are living in times not unlike those of Reconstruction, where the entire country is sitting at the crossroads - deliberating over continuing down an imperfect route that nevertheless leads to improvement, or hurtling ourselves down the path of mass political murder. Or, as Trump likes to think of it, "one really violent day." Cool!

David Noble's "The Religion of Technology," which had been sitting on my shelf of science and technology studies books for approximately forever. It's a brief historical work about how religion and technology have always been intimately linked with one another in Western culture, contradicting the still all-too-common myth that history's great technologists were motivated by the crystal clear light of pure empirical reasoning, or whatever.

Indeed, almost all of the great 17th century scientists you learned about in high school were highly focused on the imminent arrival of a new millennium that would, via scientific innovation, restore humanity to the elevated position we enjoyed before Adam (and Eve, but they weren't much interested in her) were booted out of Eden. Consider how Sir Isaac Newton was mostly motivated in his works by growing closer to the full knowledge of the mind of god, produced a bunch of work on alchemy - which is largely shoved in a corner to protect his modern reputation - and also was enough of a 1600s edgelord to (probably) subscribe to Arianism.

In our current era of ever-more-frothy Silicon Valley predictions about how the rise of chatbots that tell people to eat glue must surely presage the imminent arrival of a new revolution in human affairs, well, it's highly topical stuff. Then came the Freemasons, a spiritual sect that is in essence devoted to the religion of technology, and then came French Masons setting the standard for global engineering as a sort of nouveau-priesthood, and then came the highly-familiar sounding idea that the rise of the telegraph would bring humanity together and save the heathen, and then, of course, we get to the grim apocalyptic notions of the Atomic Age.

Noble's book came out in 1997, but it still provides us with crucial context for what are we forced to deal with today. We are inundated in predictions from tech executives - people whose primary area of expertise resides in consuming ketamine, - that we are teetering on the very brink of human apotheosis, all thanks to a nearly-holy machine soul that is, as I write this, telling actual human patients that they've received crucial vaccines they have not actually received. Religion and technology never did detach from one another, much as the most annoying Javascript-jockey lurking in the depths of Reddit's philosophy sub might wish to believe.

It is important to know that this is true.

"Art"

I'm drawing again. Because it's October.

Here's some animals in boots.