Noticing the View From Above: Thomas Baldwin's Airopaidia

“Nor did the Eye seem to want the Aid of Glasses: as every Thing, that could be seen at all, was seen distinct.” - Thomas Baldwin, on the occasion of his first ascent into the air in 1785.

In the late 18th century, the term “Aeronaut” was reserved for the small minority of people bonkers enough to willingly up in an early and extremely dodgy hot air balloon. Between the first manned balloon flight in 1783 and 1786, Europe was seized by a passion for ballooning, a craze that spawned many daring feats and weird stories.

One such aeronaut was Thomas Baldwin, a now mostly-forgotten English ballooning enthusiast, and it is a shame that he has largely receded into history. That’s because Baldwin was one of the very first aeronauts to think to write not just about the technical details of ballooning, but also of the experience - and the visuals - of ascending into the air.

In 1785, a mere two years after manned ballooning was invented, Baldwin flew in a balloon from the British town of Chester. It was not, much to his sorrow, his own balloon: he had tried to construct his own from a kit and had failed in the endeavor.

It was instead owned by the eminent Italian aeronaut Vincent Lunardi, who had taken it to Chester as part of his traveling “Flying Circus” exhibition (which explains a lot to modern-day Monty Python fans). Lunardi had burned his hand with some type of acid the day before his Chester ascent, and was unable to fly. He agreed to let the enthusiastic Baldwin take his balloon for a spin in his place.

After these two ascents, he wrote “Airopaidia,” a vivid account of his experience, illustrated with a few lovely color plates of Baldwin’s own drawings, representing the view from above. And it is a remarkable thing to consider in 2021.

Consider how unfathomably weird it must have been to go up in a hot air balloon in the 1700s. People certainly did have maps, and the ability to look at the world from high peaks and towers, before hot air balloons were invented. But they could only climb so high, and you still looked down on the world from a decidedly slanted, oblique perspective.

Suddenly, with a balloon, a person could look flat down at the earth, vertically. Balloons turned the imagined abstraction of maps into something real, something people could look upon with their own eyes. The earliest aeronauts were, very genuinely, looking at something that no human being had ever looked at before.

I've been reading a lot about the aerial perspective these days, as part of a book I'm writing on civilian drones. The book will be about what drones are (which is complex enough in and of itself), but I also want part of it to be about what drones - and the aerial perspective they inexpensively afford - mean. For surely it must mean something, to suddenly make it so easy to see the world from above, just because someone feels like it, without the mediation of Google Maps or expensive photos from expensively-piloted manned aircraft.

Drones are much older than people think they are - at least as old as manned aircraft, if not, arguably, older - and human knowledge of the aerial perspective goes back far earlier than the Wright Brothers as well. The main new thing about the aerial perspective in the 21st century is that vastly more people are able to access it, via channels like Google Earth and camera drones so cheap you can impulse-buy them on the Internet.

This was very much not the case in the early era of manned aviation in hot air balloons, which, after all, took place before the invention of photography, much less aerial photography. (That arrived around the 1860s).

In the late 1700s, while hot air balloons were becoming more widely known and popularized, they were still a terrifically expensive and persnickety thing to own. Much like the DIY model airplane and drone hobby worlds of today, most participants were well-off men who could afford both the time and the cash expenditure.

You could even send away for a balloon to build yourself from a catalog, like Baldwin did, just like you can buy drone parts off the Internet today.

Thomas Baldwin, writing his treatise (as such publications were charmingly called back then) in 1786, sounds eerily like the hobbyists, drone and otherwise, we encounter today. Airopaidia is split into technical experiments, observations on the aerial journey itself, and some technical content (for the academically minded).

Just like any modern dork, Baldwin has effusive praise for all the wonderful gifts that hot air balloons offer humanity. At the start of the book, Baldwin praises the view from a balloon as the sort that might "raise the most careless mortal to an unknown degree of enthusiastic rapture and pleasure.”

After initial preparations, Baldwin was able to get himself safely into the air, fortified with brandy and scientific equipment.

Consider how he describes his first look at the earth from above. His wording is quite similar to how people would describe trips on LSD in the 1960s:

“But what Scenes of Grandeur and Beauty! A Tear of pure Delight flashed in his Eye! Of pure and exquisite Dlight and Raptrue; to look down on the unexpected Change already wrought in the Works of Art and Nature, contracted to a span by the NEW PERSPECTIVE, diminished almost beyond the Bounds of Credibility.”

He becomes one of the first people to experience the eerie nature of sound in the upper altitude:

“The gay scene was Fairy-Land, and Chester Lilliput. He tried his Voice, and shouted for Joy. His Voice was unknown to himself, shrill and feeble.

There was no Echo.”

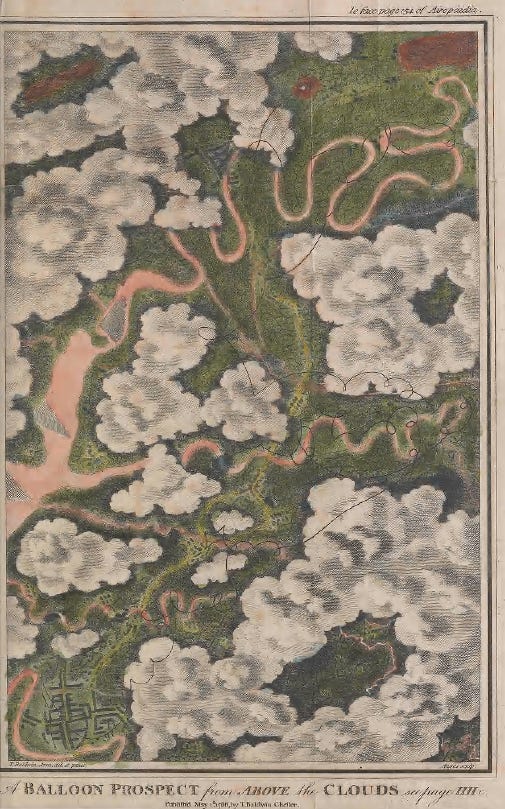

Baldwin observes with awe how landmarks that he is familiar with, like roads and rivers, changed color and appearance at great distance: of the River Dee, he finds that cannot “discover even the Appearance of Water; but merely that of a broad red Line, twining in Meanders infinitely more serpentine than are expressed in Maps.”

He becomes aware of how altitude flattens even the tallest objects, not even the local cathedral, while also lending them vibrant and unexpected color. “The Whole had a beautiful and rich Look; not like a Model, but a coloured map.”

While the balloon meandered in the direction of the nearby sea, Baldwin reassures the reader that he wasn’t worried: he was capable of rising into an air current that would keep him on the land.

As his flight continued, he contemplated that he had left his native earth for the first time, and was now entirely separated from the crowd of 4000 on the ground that had seen him off. Which he seemed to think was a pretty good thing:

“An universal silence reigned! An empyrean Calm! Unknown to mortals upon Earth… A cheerful serenity filled the Breast of the Aironaut.”

At another point in his second balloon ascent of the day, he returns to this concept of perfect silence and calm:

“And thus;' for a while detached, far detached from Earth, and all terrestrial Thoughts; wrapt in the mild Azure of the ethereal Regions; suspended in the Center of a vast and almost endless Concave; come, as a mere Visitor, from another Planet; surrounded with the stupendous Works of Nature, yet above them; — the Glorious Sun except, which enlivened ALL, and shone with pure celestial lustre ; — a peaceful SERENITY of Mind succeeded; an enviable EUROIA. An idea of which it is not in the Power of Language to convey or to describe.”

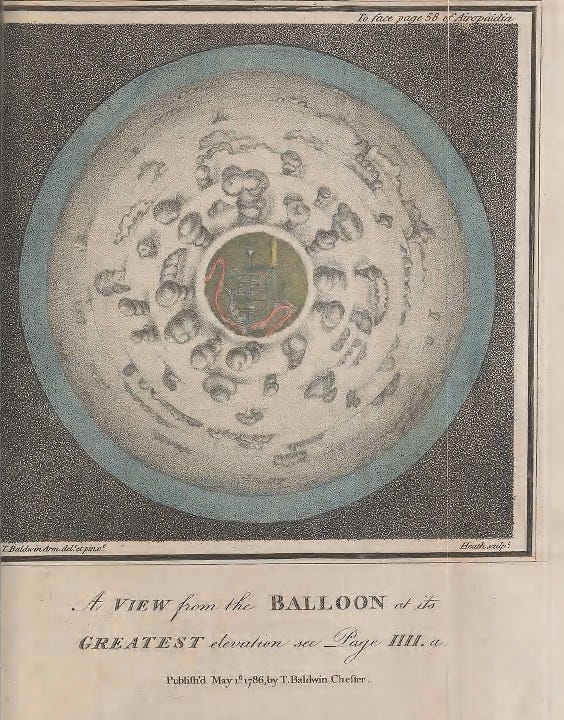

He notes the splendor of the clouds (which he regarded from a wholly new perspective), and is also deeply impressed by the colorful shadow - encircled with color, like the iris of an eye — that his balloon put off. He called it a “celestial Phantom,” which accompanied him here and there, blinking in and out.

For some scientific reason, Baldwin had taken a trained homing pigeon with him, which he released at a high elevation, although it “trembled much.” The bird eventually flew off back to its owner on the ground. He also conducted a tasting experiment, where he sampled pepper, salt, and ginger, which retained their “usual pungency”: apparently, travelers had reported that condiments lost their flavor on the lofty Peaks of Teneriffe.

During the second flight, he ended up coming down in a field somewhere he could not identify, but the country people who rushed up to see what was up with the sudden appearance of a balloon told him he’d come to earth in Lancashire. He gratefully accepted their offer to walk him over to a road, and “shared his liquor among them.” He then proceeded to give curious local people rides in the balloons car at a altitude about the height of the trees, while he and a procession of people held fast the rope and walked beneath it. Some people liked it more than others:

Which brings us to the really interesting thing about Baldwin and Airopaidia.

Weirdly enough, as Dr. Marie Thébaud-Sorger points out in her chapter in the excellent “Seeing From Above: The Aerial View in Visual Culture,” Baldwin was perhaps the only balloonist of his era who actually bothered to write, in detail, about the actual experience of ballooning. While Baldwin says this himself in the opening of Airopaidia, it’s easy to dismiss it as the usual egotistical puffery from 18th century Men of Science.

But in this case, he was right.

The other eminent balloonists who might have commented on the more metaphysical aspects of balloon perspective were, Theubad-Sorger suspects, preoccupied with the engineering details of the balloon, concerned about perfecting aerial navigation, and (most understandably) worried about keeping themselves from dying a fiery death. They saw little value in devoting much sentimental, gloppy thought to what it actually meant to be a human being taking in a view that no human being had ever taken in before.

Or perhaps, to take another view, these engineering-minded aeronauts were simply too overwhelmed by the weirdness and newness of the perspective that they didn't feel equal to describing it. (Knowing what I know about the egos of wealthy 18th century balloonists specifically, and wealthy nerds with intellectual aspirations generally, this seems unlikely).

Whatever the reason, most early balloonists had a lot to say about ballasts, rigging , and air currents, but they didn’t have much to say about the aesthetics of ballooning, or the vast weirdness of looking at the earth from above. But Baldwin did. He was one of the first prose stylists of the air.

Not that he got much out of it. Baldwin’s unusual willingness to wax poetic about viewing the world from above did not win him a massive readership. While his book also did include plenty of fancy technical details about balloon travel logistics like other early treatises on flight, Baldwin’s timing was terrible.

The ballooning fad was on its way out by the time his book was released. People were growing more cynical about the practice of ballooning and its future possibilities and implications. People were growing less impressed by reading about the exploits of wealthy, bored men, men who floated over their earth-bound heads in hugely expensive gas-filled balloons.

Air or balloon travel for the average person still loomed far off in the distance. (In the 1860s, captive balloons that could accommodate a number of people on a platform would be introduced). Aeronauts experiences still remained, for most, something of a freaky abstraction that had little to do with them - the 18th century equivalent of, say, watching Jeff Bezos blast off to space in a rudely-shaped spaceship during a global pandemic in 2021.

It would also be many years before aeronauts figured out how to take aerial photographs, the undeniable and shocking images that would truly familiarize the world with what the Earth looked like from above. Until then, drawings like Baldwin’s were about as good at it was going to get.

Some people of the time also worried that balloons were harbingers of something far darker. Here’s Horace Walpole speculating darkly (and, let’s be honest, quite accurately) on the future of balloons in a 1782 letter to Horace Mann:

“I hope these new mechanic meteors will prove only playthings for the learned and the idle, and not be converted into new engines of destruction to the human race, as is so often the case of refinements or discoveries in science. The wicked wit of man always studies to apply the result of talents to enslaving, destroying, or cheating his fellow creatures. Could we reach the moon, we should think of reducing it to a province of some European kingdom.”

Like most of history’s prescient nerds, Baldwin was well aware of the public’s growing distrust of manned flight. He writes at the beginning of Airopaidia, in a tone that will be profoundly familiar to anyone who’s ever looked at StackOverflow:

"Yet nothwithstanding, as ignorance is known to be the parent of fear, the bulk of mankind, which are by far the greater number, will long continue to entertain absurd apprehensions concerning it [manned flight] ; to oppose and ridicule the invention ; as they will oppose every other discovery which they have neither the talents, inclination, or leisure to understand."

Boy, does this sound familiar. I’ve had this conversation with other people-who-build-drones. I’ve probably said something similar myself. We, the early adopters of whatever - drones, the Internet, probably indoor plumbing - have been this way throughout the course of human history. We praise the wonderful qualities of our technology, and grumble and growl about how Luddite normies are too dense to grasp the sublime qualities of what we can do with it.

Baldwin takes a similarly offended tone when he addresses the question of what balloons are good for.

“It seems a favorite question among those who take a pleasure in objecting to every thing they neither do nor will understand to ask “Of what use can these balloons be made?”. And without waiting for an answer, to say “They pick the pockets of the public, risk the lives of the incautious, encourage mobbing and sharpers, and terrify all the world.”

Much like I find myself doing today on the topic of drones, Baldwin chalks much of this apprehension up to balloons novelty. He imagines that people from different walks of life might find a useful purpose: balloons to be used as stage wagons to carry things or to deliver the mail, or into comfortable carriages for rich people, which would “save one a couple of sets of horses, and would eat nothing… dress for court as we do, and make Nothing of it.”

He also grumbles that the French have thoroughly beaten the British in the field of balloon research because while they “admire liberty, Montesquieu’s “Spirits of Laws may determine; but they are not addicted to Politics…their nobility are endowed with a liberal and enterprising spirit…. They have leisure and are sober.”

Meanwhile, the British spend their time “among the beasts and birds, the other half, at the bottle, and in political cabals. Present profit is almost the sole motive for excellence in Great Britain: and experiments not made with that view are seldom repeated; are overlooked and forgotten.”

Baldwin does imagine his own uses for balloons, which mostly consist of using them as a platform for all manner of scientific experimentation on phenomena like the direction of the wind, air temperature, and electricity.

He also contemplates how they could be used to “throw principal men into a town : and convey others out of it,” and how they might become a comfortable air-borne means of traveling from town to town. What of the value of looking at things from a higher elevation? In one line, he tentatively remarks: “Geography may become a new science.” And indeed it would.

But perhaps Benjamin Franklin would have the final word on the subject of the utility of balloons, after he observed that very first Montgolfier flight in 1783 Paris:

"Someone asked me, ‘What’s the use of a balloon?’ I replied, ‘What’s the use of a newborn baby?’"

You can read the entire text of Airopaidia at the Internet Archive.