Rejecting Reality in the Age of AI

In 2025, many people don't just believe that Online is of equal importance to Offline. They believe that Online is the only place that really matters at all. I look into how the Internet and AI are encouraging more and more people to deny reality itself.

In early 2020, as the world began to close down in the face of Covid-19, I was taking a shower and had a sudden, terrifying thought: this pandemic will usher in the most terminally online period of history that humanity has ever known.

This prediction continued to haunt me throughout the early lock-down era, as I found myself, an already extremely online person, spending more time unblinkingly and incessantly scrolling social media than I ever had before, or ever, God knows, actually wanted to before.

On social media, I watched as both a heroic global public health movement and a deranged anti-vaccine coalition began to coalesce, organize, and fight one another on the coronavirus battlefield, a process that occurred both in the ever-more-distant seeming offline world, and in the far-more-visible and stupendously fast-moving venue of pre-Elon Twitter.

Which left me with more, equally unpleasant questions:

What new social mutations and pathologies would emerge in the face of a year or more in which the bulk of all human interaction took place over the Internet?

What creeping caterpillars of batshit might weave themselves social media quarantine-cocoons and eventually emerge as freak-ass butterflies, endowed with newly-formed opinions and the power to vote?

How would millions of previously not-very-online people adapt to suddenly being forced by circumstances to become extremely online, and how would their presence alter the digital grassland across which many of us have already been roaming for years?

As I write this today, in 2025, still lack many good answers to these questions, and I anticipate that a bunch of patient scholars will be studying how the social disruption of Covid-19 impacted our culture and our politics until well after we're all dead.

But I do believe this much is true: the sudden forced onlinefication of huge swaths of society in 2020 played a major role in making U.S. culture and politics weirder. More chaotic and unpredictable. More driven by memes, whims, micro-trends, and the capricious desires of a core user-base of poorly-socialized and out-of-touch-with-reality people.

More, well, like the Internet.

Nor did this process of ever-intensifying beweirding stop there. In late 2022, OpenAI released its first consumer LLM tools into the teeming and increasingly malaria-ridden fever swamps of the post-Covid Internet. And all hell broke loose.

Today, at the end of what has been both the absolute dumbest year of my life and quite plausibly one of the dumbest years in the history of mankind, I want to at sketch out at least the faint outlines of another thought that's been haunting me in the shower:

In 2025, many people don't just believe that Online is of equal importance to Offline. They believe that Online is the only place that really matters at all.

I pair this conclusion with a memory, of the distant and disappeared era before the 2020s flew into the picture and started frantically shitting everywhere, like a seagull unexpectedly trapped inside of a coastal hotel room.

During my own extremely online childhood and teenage years, back in the late 1990s and 2000s, I remember hearing a lot of public hand-wringing about the dangers of young people succumbing to the delights of the digital world.

truly there was Concern

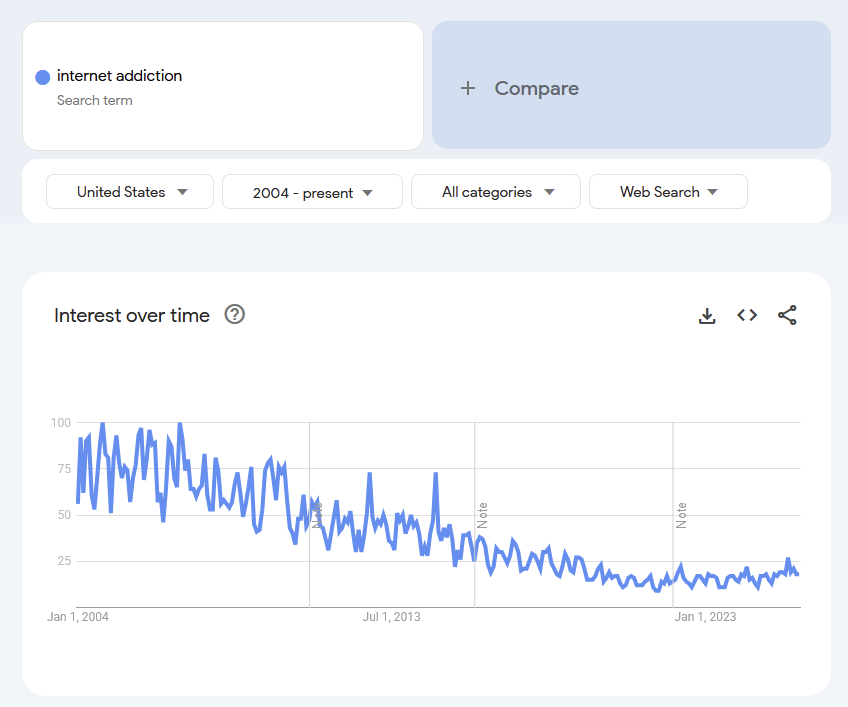

Very serious pundits with very serious bow-tie collections first began to throw around the term "internet addiction" (based off the work of far less prominent, and far less broadly alarmist actual researchers) and then proceeded to haphazardly apply it largely to teenagers - shiftless adolescents who they imagined were rejecting the pleasures of reality-based high school life in favor of World of Warcraft and anime forums.

In South Korea and China, worried adults set up boot camps intended to break overly-online youth out of their perceived digital prisons, American parents fretted about MySpace, and laughably easily-circumvented tools that purported to control kid's screen time first began to hit consumer markets.

One unifying fear ran through it all: that teenagers might spend so much time screwing around on the computer, they'd lose touch with the far more important and developmentally vital world of the real.

"Important" being the operative word, because to most serious adults in the 2000s, it was utterly and obviously self-evident that The Internet was just an inferior shade of a greater reality - profitable and interesting, certainly, but not a platform which steered the world, or even the world's conversation.

At the time, I believed these fears of teenagers rejecting the complexities of the offline in favor of the comforting certainty of anime fanfiction forums were largely overblown.

misty golden memories

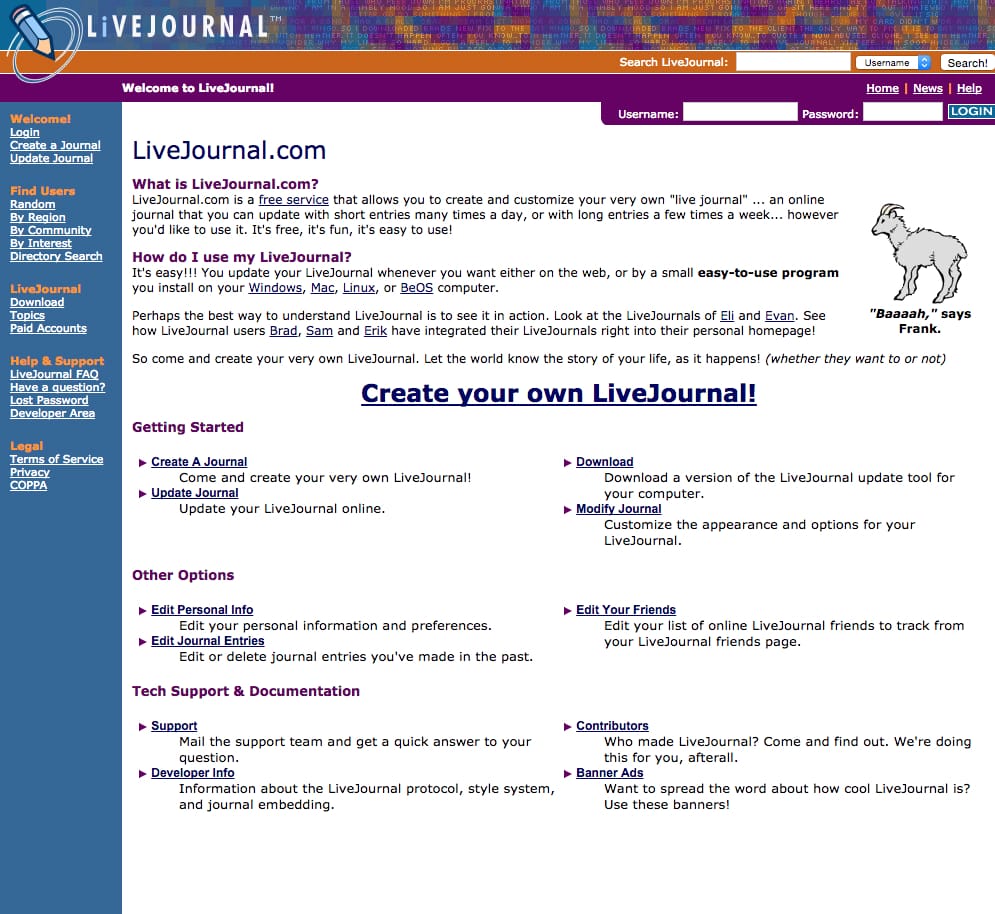

The Internet was different then: smaller, more intimate, a tool that still appealed most to oddballs, weirdos, and members of niche and geographically-distributed subcultures.

As an extremely online kid, I spent my time posting in small-scale Internet forums where I didn't have to worry about my inane adolescent takes being plastered all over network news and commented on by the President. For eccentric kids like me, the Internet functioned primarily as an appealing escape from the awkward day-to-day of shuffling around high school - a way for us to make friends who shared our interests, many of whom I still talk to today.

Equally importantly, the Internet was a place where the adults in our lives were not - or at least, they didn't know where to find us, in that epoch before Facebook decided it was a good idea to force the planet into constant online communication with every single annoying person in their extended social universes (which I wrote about here).

I've come to believe that my early-ish Internet years, in an era in which the Internet was less sanity-destroying and total than it was today, gave me and most of my nerd-ass peers a fairly gentle introduction into being extremely online without going completely insane.

For people like me and my friends, while we certainly liked the Internet, we were largely aware that there was more to life than our social media accounts.

Which is exactly why American cultures sudden turn towards blurring these boundaries - at the very highest levels of power and influence, and largely amongst people who lacked my formative teen years in the early shitpost mines - keeps me up at night.

Today, that 2000s fear of people succumbing to Internet addictions so potent that they stop being able to grasp the boundaries between offline and online may very well be coming true, fueled by chatbots, ever-more-predatory social media platforms, and the mass getting-online event that was Covid.

It's all just happening in a far weirder, and far harder to control way than most anyone could have imagined. And crucially, it's not just happening to teenagers.

I vividly remember those years when the world's important adults first began to realize en masse that the Internet really could reach out and touch global affairs.

I like to think that this tendency really kicked into gear in 2008, when Barack Obama's youthful campaign staffers were widely credited with figuring out, for the first time, how candidates could use the Internet to get out the vote. In 2009, Iranian activists relied heavily upon Twitter to orchestrate what became known as the Green Revolution, a then-novel practice that attracted bemused headlines around the world.

Then 2010 and the eminently online organization of the Arab Spring hit, and suddenly, for a few years that in retrospect seem so utopian that I sometimes wonder if I dreamed them, a lot of very smart people started to talk about how the Internet might prove to be an astonishingly powerful force for promoting global democracy.

For a brief and shining moment, consensus formed that the Internet couldn't just impact global affairs - it promised to do so in a way that would make the planet better, ushered in on the back of Mark Zuckerberg's creep-ass decision years earlier to make a website where he could rate girls.

Well, we all know how that worked out.

Along came 2016, along came Donald Trump's social-media (and Russian) assisted election.

Along came the dawning and woefully under-acted-upon realization that the Internet might actually not be a shining force for good after all.

Initially, I thought it was a good thing that more decision-makers were finally recognizing that the demons, wraiths and Donald Trumps of the digital world occasionally could slime their way right out of the screen into your room like that stringy-haired child from the Ring movies and murder you (mostly metaphorically).

And for a while there, during the shock-and-awe phase of the first Trump administration, I think that we collectively did start to make a certain amount of progress towards untangling how the Internet relates to the offline, the complex interplay between the two, and how both bad and good actors can use social networks to impact human behavior.

Then Covid happened, and everybody and their parrot got online. [[1]]

Far off in the distance, I could hear the soft and susurrating sound of the worms that had hatched in far too many influential brains beginning to really munch.

In little whispering voices, the worms began to ask what would happen if the Internet was the real world.

Since 2020, like so many of you, I've been forced to watch Clockwork-Orange like as a critical mass of people, many of them unthinkably rich and powerful, develop Internet habits so crippling that they'd have made a 2005-era finger wagger die of an immediate coronary event.

And most terrifyingly, too many of those people have concluded that the Internet isn't just important, more so than they'd previously realized.

They've come to believe that being big online is the only thing that's important, to an extent that would have given even high school me the heebie-jeebies.

What happens when someone desperately needs to touch grass, but they appear to have forgotten that grass ever existed?

No creatures exemplify this problem more elegantly than both Donald Trump and the flesh-eating remoras that trail in his wake.

If Covid launched the most extremely online period in human history, than Trump 2.0 is the grotesquely mutated result - replete with far too many frantically-waving tentacles and watery eyeballs - of exactly what happens to beings who have spent the last six years sticking their whole entire faces directly into the Internet firehose.

There are so many staggering examples of the Trump administration and Trump himself cheerily rejecting reality over the last year that someone could write a book, and I am sure someone will. I will linger here on just a few examples.

some classic Elon Musk takes on humanitarian aid

Hitting close to my own professional home, consider the psychedelic absurdity of how the dual demons of the Trump administration and Elon Musk decided to unceremoniously drag USAID behind a building and shoot it, within a few short weeks of the inauguration ceremony.

I believe that this act of enormous cruelty was absolutely fueled by Internet is Everything Syndrome.

Researchers agree that Musk's intense and bizarrely specific hatred for USAID (a grudge that likely kicked into gear when the agency launched investigations into Starlink's actions in Ukraine) was almost certainly fueled by the tempting buffet of conspiracy theories and slander that the users of Twitter, his very own social media website, constantly laid before him.

Despite the fact that a sea of experts, including people as prominent as former USAID administrator Samantha Power, attempted to get Musk to change his mind by means of facts, figures, and logic, he was openly contemptuous of them all, accusing everyone who pushed back on him of being a corrupt liar. Within Musk's worm-eaten inner world, experts with real-world expertise are irrelevant: to him, only the opinions of posters matter, and specifically, the posters who populate his own social media fiefdom.

And thus, in no small part thanks to the mechanism of social media, a small group of Twitter fuckwits were able to play a huger part in convincing the world's richest man and his MAGA federal government enablers to swiftly destroy the world's biggest foreign aid agency - an act that has already killed hundreds of thousands of innocent people as of this writing, and will likely kill millions more.

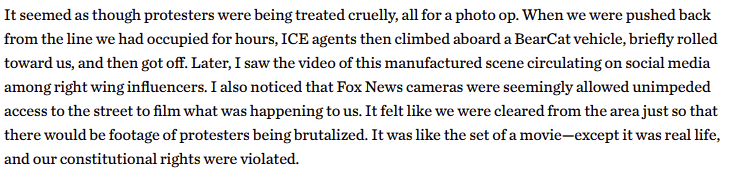

As exhibit B, consider how the Trump administration openly and totally shamelessly admits that they're orchestrating ICE raids and terrorizing people for the explicit purpose of creating internet content, and thus manipulating reality in the social-media driven form and fashion to which they are most accustomed.

Take the account of Chicago Baptist minister Michael Woolf, who was assaulted by ICE agents in early October at a protest at the Broadview detention center:

We can also look at the repulsive midnight ICE raid on a Chicago apartment on September 30th, in which 37 people, including small children, were torn out of their homes and detained for hours, as a Black Hawk helicopter flew overhead. The detainees were intentionally paraded in front of TV cameras with unobscured faces, and the Trump administration swiftly posted an action-movie style video of the event on the official Homeland Security Twitter account, hunting for the likes that seem to sustain the entire MAGA apparatus.

While Trump's government claimed the raid took place because Venezuela's Tren de Aragua gang had, for some mysterious reason, decided to entirely localize its U.S. operations in a single residential apartment building, this proved to be a bald-faced lie. Ultimately, as ProPublica found, the raid resulted in zero criminal charges, and the government still has yet to provide any evidence connecting anyone detained in the raid to terrorism.

But was that even the point? Or was the point, in fact, primarily and possibly exclusively to collect yet more sordid video focused on masked ICE agents in tactical gear roughing up bleary-eyed and confused-looking brown men, raw meat meant to be ground into sausage for the MAGA social media machine?

As a final and most profoundly terrifying example, we can look to Trump's wildly illegal and reckless strike on Venezuela on January 3rd, 2026. While a bevy of questions remain as I write this about why and how this bizarre move to capture and kidnap Maduro took place, it is already obvious that Spectacle, that the potent imagery of masculine special forces parachuting in at night to yoink a head of state out of his bed like an errant cat, was a key part of the administration's motivation (as my friend Paul Musgrave has elegantly examined).

Yes, spectacle has always been a part of politics and the broader exertion of power throughout human history, as a bunch of Continental theorists have been trying to warn us about for a very long time. But now, I'd argue that The Spectacle has genuinely grown to such an immense size that it has consumed the entirety of American politics.

Indeed, MAGA's shockingly successful effort to replace the real with Content has quite possibly been its central and most impressive innovation. Controlling the spectacle, being granted the power to orchestrate these media moments in such a way that the entire world is forced to pay attention, whether they like it or not - to the fevered Trumpist mind, that's exactly what power is for.

From this perspective, if a tree falls in the forest, or an innocent immigrant is snatched from the street and departed to a foreign country - than if no one posts about it, it might as well not have happened at all.

And if someone does post about it? Well, who's to say they're not merely posting AI slop of their own? And who has the right to deny the preferred reality of the American empire (as eloquently expressed by that unnamed George W Bush official in 2004), or at least, the American empire as envisioned in the ever more fevered and ever more terminally online minds of the modern GOP? [[4]]

This isn't all MAGA's fault.

Our recently intensified reality-rejecting turn must also be laid at the feet of modern AI companies, and the hype men that promote them. Over the last few years, you've seen the headlines: grim accounts of AI-induced suicides, cheery-toned workplace pushes to force employees to incorporate ChatGPT into their daily routines (or else), and unsettlingly high-seeming venture capitalists staring into the camera without blinking even once as they expound on how LLM chatbots will soon be able to replace knowledge workers, in pretty much any job.

In other words, AI has combined with the MAGA movement to produce reality-denial Voltron.

How, and why, did this happen?

I'm still brushing up on my artificial intelligence and cybernetics history, but here's how I see it, so far.

Humanity has long dreamed of the possibility of creating artificial intelligence, a tradition that can be traced back all the way to Ancient Greek myths concerning robot-like servants and guardian machines. We have long combined with this desire to create autonomously-moving machines with a fascination with artificial intelligence, both as a means of explaining how our own minds came to be and how they function today, and as a blueprint for being able to create mechanical minds of our own at some point in the far-off future.

To shamelessly and recklessly condense a whole lot of history down, eventually we hit the 20th century, the rise of computers, and pioneer technologist Norbert Wiener proposing in the course of his mid-century creation of the field of cybernetics - and let me emphasize here that I like Norbert Wiener - that humans themselves are "not stuff that abides but patterns which perpetuate themselves."

While scientists were highly enthusiastic about the prospect of sophisticated computer-dwelling artificial intelligence during the middle of the 20th century, and made a number of intriguing advancements, their research eventually hit something of a wall, leading to a so-called extended "AI winter" that essentially lasted all the way up to the 2010s. [[6]]

As the tech hype of the late 2010s focused its attention on crypto, drones, and the blockchain, in 2017, a team of researchers at Google first published a truly modern version of the transformer architecture (marvelously well explained here, as well as here) that led directly to today's current explosion of consumer-facing LLM chatbot technology.

These remarkable new advances in so-called generative AI systems largely flew under the radar until late 2022, when OpenAI first unleashed its consumer tools upon the world. To the assortment of techbros, VCs, and bottom-feeding Twitter hustlers of the era, who had been growing increasingly nervous as they watched both NFTs and the Metaverse fail to deliver, it must have felt like deliverance. To everyone else, it felt like whiplash.

All of a sudden, the exact same guys in $4000 designer "streetwear" (whatever that means) were now trying to convince their core audience of deep-pocketed and shallow-brained investors and executives that they didn't need to buy badly drawn ape pictures after all.

oh no they tried to warn us

Instead, they should focus their attentions on the impending AI revolution (which might very well bring with it the birth of an intelligence far superior to our own),and its suite of applications that promised even more mind-boggling riches than NFT schemes could ever cough up.

As for the average peasant, the AI hype beasts had far less to say to them - other than a constant drumbeat of warnings that the average desk-worker would need to prepare for a swiftly-incoming and totally inevitable future in which they and their expertise could be readily replaced with an LLM chatbot.

In other words, at least according to the chattering Twitter classes, and your boss's boss's boss, and a bunch of other simultaneously spooked and curiously aroused people with very deep pockets, then we were teetering on the cusp of a genuine revolution. A revolution that happened to fit very nicely with MAGA's pandemic-era fueled belief that nothing matters more than the Internet.

According to them, Online imminently was going to become Everything.

There is a vast and dense sea of literature out there that grapples with topics like artificial intelligence, automata, and how religious belief overlaps with belief in the power of technology. I've even read some of it: you probably don't want me to attempt to summarize all of that here.

Instead, here's a few points I found interesting from Fred Turner's fascinating 2006 book "From Counterculture to Cyberculture."As Turner argues, the modern tech culture of today was largely created and defined by people who spent their youths in the midst of the 1960s counter-culture drive towards utopian-minded and communal off-the-grid living, best defined in many respects by the oeuvre of "Whole Earth Catalog" founder Stewart Brand.

Many of these people ended up working on personal computing technology and the Internet during its infancy, bringing with them their earlier hippie-era fixation on personal independence, transcendence of the confines of the human mind, and system and network theory (among other things). And is so often the case, these tendencies eventually mutated into something

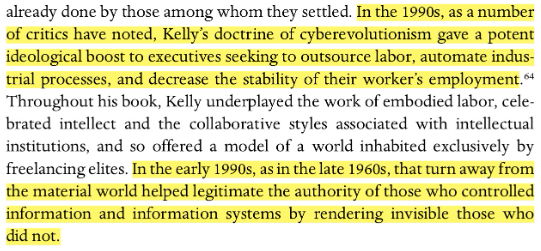

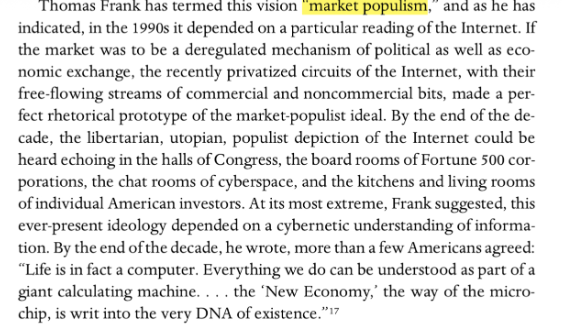

Here's Turner on Wired magazine editor Kevin Kelly's highly influential 1988 book "Out of Control", regarding the shift in the early 1990s to the Online dominated world of today:

A similar point is made by Thomas Frank in 2001's "One Market Under God":

As Frank points out, much of the grim program of regulatory destruction that we are confronted with today is linked to 1994's "Cyberspace and the American Dream: A Magna Carta for the Knowledge Age," bringing together Electronic Frontier Foundation board member and noted technologist Esther Dyson, wretched supply-side misogynist George Gilder, influential "radical centrist" writer Alvin Toffler, former Reagan science advisor George Keyworth - and, most sinister of all, the puffy-haired and shark-eyed avatar of evil known to mankind as Newt Gingrich. [[2]]

As the kids said about six years ago, that's a nightmare blunt rotation.

The very first sentence of their document makes my point for me:

And who sponsored the conference at which this document came together? Why, the ominously named Progress and Freedom Foundation, closely linked to both Newt Gingrich and his suspicious financial dealings itself.

By this means, we can link the cultural vanguards of the 1960s who did so much LSD that they tried to levitate the Pentagon - a joke that also in many ways wasn't one about the power of mind to overcome the stalwart nature of mundane physical reality - to the AI evangelists of our time.

Today, an unsettlingly large number of our modern tech industry revolutionaries genuinely believe that mind has won out over matter. After years of constant marination in Internet bullshit, AI slop, and impressive-sounding CEO announcements, many have become the kind of people who really do think that chatbots will imminently replace huge swaths of American jobs, that AGI is (probably) on the horizon, and that that metaphorical Pentagon really will rise way up in the air and turn orange, any minute now.

Moreover, they've come to firmly believe that anyone who isn't convinced by this whole Pentagon-levitation business will be, inevitably, Left Behind to roll around like underfed and stringy hogs in the muddy ditch of poverty and irrelevance.

But why wouldn't they think these things?

Nowadays, the richest man in the world, the President of the United States, and a host of tech CEOs and influential entertainers all seem to agree that the Pentagon can be levitated, Venezuela should be invaded on the basis of vibes, DEI can be crushed by means of find-and-replace, and that DC's most famous federal venue for the performing arts was always named the Trump-Kennedy Center.

When Online Becomes Everything

How seriously should we be taking the techbros on conference stages who hand-wave about how AI will automate "80% of high value jobs by 2030," and about how in "the next 10 to 20 years, AI could take over the rest of the work humans perform"?

To follow the implications raised by these tech-bro folk beliefs, what dangers might arise if we realize their vision of a near-future society where most everything "high value" is legible to AI systems?

So, here's the first truth I hold to be self-evident:

Generative AI tools are inherently creatures of the Internet and of the digital world.

They can no more exist outside of this electronic ecosystem than a goldfish can survive when tipped out of its tank onto the sidewalk on a hot day in July. If you destroy the data ecosystem within which they "live", they will also, at least in a metaphorical sense, "die."

From this truth follows a second:

An LLM-powered chatbot is only capable of knowing what is on the Internet.

All else is obscured to it. An LLM does not possess a physical form that can collect non-digital information on its own.

Which brings me to a third truth:

The entire world is not legible to the Internet, and thus, the entire world is not legible to LLMs.

Of course, I'm not the only person who has noticed this very obvious fact. [[3]] And yet, I'm still constantly taken aback by how many people seem to assume that the entire world is already comprehensible to Online, and thus, to AI systems.

Today, a large number of otherwise reasonably well-informed and well-meaning individuals genuinely seem to believe that we have already passed the Digital Surveillance Event Horizon. These are the people who, whenever they encounter news about a data breach or secret tech surveillance platform, say something along these lines: "They already have all of our data already, so I'm not going to worry about this."

and did the computer ever move in, am i right

These defeated souls assume that in the year 2026, there is no human interaction or current event that still remains obscured to the great and unblinking eyes of Internet-connected surveillance cameras, silent browser-based activity trackers, and GPS receivers that lurk within many modern devices - eyes that are, moreover, controlled by unseen and shadowy corporate and government forces which have already become so all-power that it is largely futile to resist them.

This is nonsense.

- Most experts agree that the majority of the world's historical archives still have yet to be digitized - which is a time and money-consuming process that requires considerably more effort than many people realize. The global progress of digitization is also highly unequal and subject to political pressures: it has advanced considerably further in the Global North and in wealthier societies, and far less so everywhere else. (While AI likely will be able to help accelerate this process, a human being still needs to physically scan and verify transcriptions, among many other tasks that these systems continue to struggle with).

- About 2.2 billion people globally - approximately a third of the planet's population - are still offline according to a recent study from the ITU. Most of these people reside in low and middle income nations, in rural and less-dense areas.

- Per data released in October 2025, about 5.66 billion, or 68.7 percent of the planet's population, are social media users - meaning that vast numbers of people still don't engage with social media platforms at all.

- While about 84% of adults in developing countries own a mobile phone, about 1 in four have a very basic phone without apps or web browser functionality - and women and poorer people are considerably less likely to own phones of their own. These stats for adult smartphone ownership also vary hugely across region, from 80% of adults in East Asia to a mere 33 percent Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Much of the planet still hasn't been digitally mapped to any degree of useful detail - or if maps of these places do exist, they are woefully out of date.

Yes, we do live in a world of pervasive digital surveillance.

There really are hugely powerful private companies and governments who have invested equally huge amounts of money and time into developing ever more sophisticated mechanisms for attempting to extract as much profitable and power-maintaining data-slurry from the meat of humanity' day-to-day existence as is humanly possible. It is also true that the data-hungry models that power the current AI feeding frenzy have created powerful incentives to make much more of humanity legible to The Online.

And yet, these deep-pocketed interests simply haven't managed to even come close to completely digitizing the world and all its affairs yet.

Even though it is very much in in their interest to make us believe that they have.

For an example of this dynamic, I'll point to the current and shamefully globally-ignored civil war in Sudan, which has killed enormous numbers of people since it re-ignited in 2023. Aid workers, reporters, and war crimes investigators have consistently struggled to secure physical access to Sudan's dangerous conflict areas and to civilians in need of support.

To get around these daunting impediments to ground truthing efforts, some specialized analysts (including some of my former colleagues) have been tracking the conflict remotely for years, by means of a combination of high-resolution satellite imagery and open source intelligence analysis. These techniques are genuinely game-changing.

And yet, remarkable as this form of remote sensing and open source analysis is, what these researchers can actually see by means of digital sensors and platforms is still very constrained - information that ultimately functions as a key complement but by no means as a substitute for physical access.

Such is the case for the ongoing investigation into what happened to the people of El Fasher, a city of over 260,000 that was captured by RSF fighters on October 26th, 2025, after a grueling 500 day siege.

While we know that the fall of El Fasher unleashed what appears to be a nightmarish wave of mass killings, violence, and displacement, we are still, as of this writing in early January 2026, very much unclear on exactly what happened to many of those people. Where they went. What they suffered. If they're still alive or dead.

Valiant and important as the efforts of remote analysts who focus on digital information may be (and they are), much is still obscured to them.

Here are some of the reasons why.

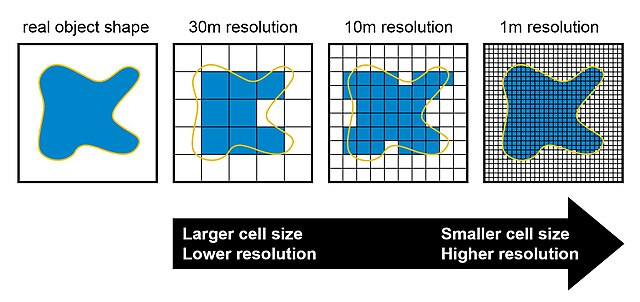

In most cases, a satellite can only revisit the same location at a maximum of about once a day. [[5]] if it happens to be cloudy at that particular time, analysts simply have to wait until it comes around again.

Further, the imagery that satellites collect has a limited and imperfect degree of resolution: the best-available commercial satellite imagery available today reaches a resolution of about 30 centimeters per pixel.

While this is certainly an impressive amount of resolution for satellite-collected imagery (albeit considerably less than the much finer detail visible with drone and aircraft-based data collection) it's still nowhere near detailed enough to provide analysts with total certainty about what they're looking at. Their work still requires nuanced and decidedly human interpretation of the imagery that they're looking at.

Analysts of open source media also face many constraints and challenges, of a kind that I don't think AI will release us from any time soon. While it's true that social media now affords us more real-time, on the ground information about global warfare than has ever been witnessed in human history, we'd be foolish to assume that social media captures everything worth knowing about.

Useful as it may be, social media inherently provides us with an incomplete, inherently biased, and increasingly easily-faked (thanks to GenAI) version of what is actually happening on the ground - in more metaphysical terms, about the nature of current reality.

What's more, in 2025, combatants in conflict are highly aware of how they can use social media to attempt to bend digitally-mediated reality in their favor.

When the RSF attacked El Fasher in October, they unleashed what appears to be a complex jamming attack, persecuting and disappearing journalists, shutting down already weakened public telecommunications networks (fighters often rely upon Starlink instead), and massively reducing people's ability to send messages out.

And the RSF are by no means the only fighters capable of executing such targeted strikes on the Internet and mobile networks. Jamming communications and shutting off Internet access is now a standard feature of global warfare, and figuring out how to defend networks from such attacks remains incredibly difficult.

Taken together, all these impediments mean that despite the absolute best efforts of a team of world-class specialists who have been working day and night for months with remote satellite and social media data to attempt to answer that question, we still have a very limited picture of the total death toll in El Fasher.

Ultimately, these remote teams will need to combine their digitally-mediated insights with information collected by experts on the ground (who, again, have only just started to gain access over the last few days) to get the complete answer. Because our current era of technological wonders still has yet to provide us with One Weird Trick that will let us skip ground-truthing entirely.

Would we still be unclear, months later, on the fate of El Fasher's people if we actually did live in a world where the digital could see everything, if reality actually did adhere to the fantasy of total global surveillance that Silicon Valley is trying to sell everybody on today?

I don't think so.

Which brings me to a second point.

AI Is Still No Substitute for Ground Truth

To reiterate: pretty much expert agrees that there is only way we will confirm what really happened to the missing people of El Fasher: by means of investigation by people on the scene. (As I write this, a very limited number of UN and NGO team members are currently being allowed into the area).

This is true because the world is not actually fully covered by surveillance technologies, to the extent that many tech-savvy Americans seem to believe it is. It is also true because LLMs are not embodied: they are not yet capable of independently moving through space to capture real-world information for The Online.

the brazen talking heads of yore also weren't great at wandering around on their own

Yes, humans can (in a sense) transport an LLM to the scene of a crime, a protest, or a mass shooting in the kinda-sorta-embodied form of a smartphone or another device capable of connecting to their software.

But the LLM still has no mechanism for getting to these locations on its own. It can only know information if some human, somewhere, creates the conditions to permit it to do so.

In theory, this need not be the case forever. We can imagine a future in which GenAI-enabled robots come trundling across the sands to investigate war crimes and to interview presumably skeptical sources on the ground.

We can also imagine a future in which underpaid and under-trained human interns are occasionally deployed to disasters and conflicts while wearing Meta's stupid Ray Ban chatbot glasses. Perhaps a GenAI-enabled service would then parse that footage and puke out something vaguely approximating a summary of what is occurring- at least, for as long as the underpaid meat robot cursed with both the ability to love and crushing student loan debt survives.

And yet, these futures all seem like bizarrely convoluted ways to navigate around what we know actually works. That is, actually sending highly-experienced and well-supported humans with prior experience in dangerous and sensitive situations to the scene to investigate, as soon as is it plausibly safe to do so.

In other words, the deployment of a well-trained autonomous agent bestowed from birth with the relevant sensors required to collect information about reality, as well as a hard-wired ability to both earn the trust of sources and to contextualize what it is seeing on the ground. (Now that's innovation!)

This leads me to a third point.

LLMs still cannot replace human reporters and analysts because they struggle to accurately represent real-time information.

Capable as they are, LLMs still almost exclusively depend on human reporters and social media users to spit out information about current events. Currently, many LLMs do this by executing web searches to find information that has hit the Internet after their model's "knowledge cutoff."

If no human being has digitized an account of current events, than an LLM cannot know about it. Nor are they all that reliable at representing current events that have been reported on by humans.

LLM users continue to report that these tools frequently will flag shocking current, recent events - such as the recent U.S. invasion of Venezuela - as hoaxes and misinformation.

Although the users who reported this issue were prompting certain LLM models well after reputable news organizations had already published stories validating that the attack on Caracas really had taken place, many LLMs simply weren't capable of reliably keeping up with the break-neck pace of reality. Due to the way LLMs operate and how models are trained, their struggles with rapidly unfolding, novel current events are likely to continue into the future.

Does this massive societal push towards prioritizing The Online mean that our society will simply attempt to re-orient itself in such a way that on-the-ground reporting is systematically devalued? To get all James Scott up in here, will we be persuaded to simply stop caring about things that aren't legible to The Online, even as those things continue to, indisputably, occur?

Yes. It does mean that. We should all be very worried about this.

Per Scott, and a number of other thinkers who have built upon his work, our physical environment, our communities, and even people themselves have all been altered in the service of becoming visible (and thus, "real") to the ever-more-complex and increasingly technological systems that run the modern world.

Frighteningly, much of this devaluation of on-the-ground reporting has already taken place.

While both the world and the media's general apathy to conflict in countries that are deemed geopolitically unimportant is nothing new, I've come to believe that our current Internet-obsessed age is making this habit of willful ignorance considerably worse.

can you even remember the last time you heard the term "foreign correspondent" unironically

Global news agencies and publications have been slashing their foreign reporting budgets to the bone for the last 20 years, a process that has only accelerated over the last year thanks to the second Trump administration's massive cuts to international media funding.

Threats to journalists in conflict zones - who are often underpaid and minimally supported freelancers - have seen a sharp increase in recent years. Meanwhile, among the ever-dwindling ranks of employed elite-media journalists, many seem more focused on covering spicy social media posts from government officials and aristocratic group chat drama than on the more difficult and increasingly under-appreciated work of actual investigative reporting.

And quite a bit of the blame for this sad degradation of journalism, albeit absolutely not all of it, can be laid at the feet of the very same tech companies whose platforms destroyed the old journalism model, and who are now feverishly demanding that everyone shove LLM suppositories up their orifices.

Ultimately, journalism is falling into the same pattern as most everything else in our society: an increasingly narrow-minded focus on only those events and affairs that can easily be analyzed, engaged with, and reported on via the Internet.

And nevertheless, even as American journalism increasingly decides to look in the other direction at the behest of their automated shepherds, deadly conflicts like those in Sudan will keep right on happening anyway.

The Dangers of Believing That Only Online Matters

Which brings me to the final reason why we must resist our current societal push towards rejecting reality.

When you believe that everything that matters is Online, you will inevitably miss crucial information from that pitiless old bitch that is tangible reality.

To use another crusty saying, you may not be interested in the real world, but the real world is very much interested in you.

Think of how the MAGA mentality consistently melts down and malfunctions in the face of natural disasters, current events which can be readily spun and propagandized, but cannot be meaningfully stopped by shit-posting on Twitter.

You can believe that LLMs can replace weather forecasters and disaster response specialists all you want (and indeed, the Trump 2.0 coalition does appear to believe this). But when an unexpected tornado comes through and destroys both your house and your wildly-expensive data center, you may live to regret it.

Think also about all those people around the world who are invisible to or barely legible to digital systems, who live and work in contexts that remain largely invisible to both the Internet and to the AI-powered systems that we are assured control the future.

Yes, the tech oligarchs and their supporters intend to capture these people eventually, to round them up into tidy and easily-controllable digital enclosures. And yet, the world is still very large, and it contains a great many things, and to render it truly legible to the Internet remains a huge and wildly expensive unfinished project.

And it is also true that the world's illegible people, ignored and little-respected as they are by the likes of Donald Trump and Elon Musk, may have their own emphatic opinions on the procedure of being eventually rendered digestible by the Online.

Over the last two decades, most people in most places welcomed the global march of internet penetration, mobile phones, and other digital technologies, bringing with them as they did the promise of expanded access to wealth, healthcare, and social mobility.

Should we assume this largely friendly attitude will remain in place if the tech oligarchs vision comes to pass (even in part) of a world where desirable jobs are primarily done by GenAI agents, and scut work is done by humans? And have the tech oligarchs become a bit too comfortable in their assumption that their technology has provided them with good-enough information about everything and everyone that might wish to oppose them?

If us residents of the world's wealthy and ultra-digitized societies decide that we can safely ignore realities that do not please us, if we conclude that everything we ever need to care about can be filtered through the medium of the Internet and LLMs, then we are placing ourselves in great and entirely foreseeable danger, both from natural and human sources.

We will be intentionally blinding ourselves to both the beauty and terror of offline reality.

Nothing ever happens.

Until it does.

[[1]]: No, really, the parrots got online too.

[[2]]: When I was in third grade, my friend and I verbally harangued Newt Gingrich at an event at the Atlanta Zoo about the plight of wild mustangs in the American West. I like to bring this up whenever I'm forced to think about Newt Gingrich.

[[3]]: One particularly famous exploration of LLMs and physical reality is "Transmission Versus Truth, Imitation Versus Innovation: What Children Can Do That Large Language and Language-and-Vision Models Cannot (Yet)," a 2024 paper that contrasts LLMs abilities to come up with new tools and novel causal structures against the ability of small children to do so. (Somehow, despite their lack of data centers and Nvidia-powered AI clusters, the kids still very consistently beat the machines).

[[4]]: According to reporter Ron Suskind in 2004, writing in the New York Times magazine: "The aide said that guys like me were 'in what we call the reality-based community,' which he defined as people who 'believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.' [...] 'That's not the way the world really works anymore,' he continued. 'We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you're studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we'll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that's how things will sort out. We're history's actors...and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do."

[[5]]: Geostationary satellites that persistently monitor a single location are used around the world for communications and weather monitoring (among other tasks), but they operate at a very high altitude and do not provide the extremely high spatial resolution required for tasks like remotely monitoring conflict.

[[6]]: This piece is already too damn long and meandering, so I had to skip doing a recap of early AI pioneer Joseph Weizenbaum's classic "Computer Power and Human Reason," a remarkably currently-topical critique of the dangers of human-sounding chatbots. You should read it.