Some Cooler Thoughts on Air Conditioning

An assortment of air conditioning factoids that didn't make it into my Foreign Policy piece

Last week, I published a piece in Foreign Policy on why air conditioning is a necessity that saves millions of lives, not a luxury that we can safely put aside in the interest of climate change. You can read it here.

Here’s a few more thoughts on air-conditioning that didn’t make it into the piece due to space constraints.

Western, European culture has one hell of a bias towards cool, snowy climates. I remember first noticing this as a kid who lived in Florida: so many children’s books depicted a “normal” American life as one lived in a place with 4 seasons, snow, and a distinct Currier and Ives aesthetic. I haven’t delved into the academic literature around this phenonomn, and I’m sure I’m not the only person to notice it. But it does create some interesting blinders when it comes to what risks people with power deem to be important enough to do something about.

While many Americans now live in snowless regions studded with palm trees, mainstream culture’s idea of what’s “normal” hasn’t really shifted in the same way.

To Europeans, meanwhile, warm, steamy places were considered rather inherently suspect, full of malaria. In the 1800s, some Lamarckian proponents of “racial science” believed that dark skin and other non-white features were diseases brought about by life in unhealthy hot climates. They wondered if the dread disease of “not being a morally superior white person” could be cured by extended periods in heathier, more temperate places.

In an early form of climactic determinism far older than “Guns, Germs, and Steel,” elites and experts like geographer Ellsworth Huntington claimed that the “backwardness” of the US South, the African Continent, and even the southern Mediterranean could be blamed on the hot, sloth-producing climates of their homelands.

Even to this day, you’ll regularly hear Europeans and Americans confidently claim that cultures in hot and steamy places only were able to match the development of cultures in cool, snowy climates due to the advent of modern air conditioning.

The 12th century Khmer builders of Angkor Wat beg to differ. I hear it gets a bit hot in Cambodia.

People are frighteningly bad at gauging their risk of death or injury from heat. A 2019 research paper found that people in hotter states perceived more danger from heat, while people in cooler states perceived less danger – which seems obvious, until you consider that there’s evidence people in typically cool climates suffer more health impacts from extreme heat events than people who are more accustomed to them do.

White people, men, and higher-income people were all less likely to view heat as a risk, which is something that shouldn’t surprise anyone who knows a few rich white men.

Worrisomely, older people, who are at greater risk from heat than younger people, had lower perceptions of risk from it. That was especially true if they resided in areas that hav - even in living memory - been a lot cooler than they are today. As the climate changes, many older people may end up being blind-sided by deadly heat waves that resemble nothing they’ve ever experienced before. The “surviving the heat” strategies they became accustomed to in the 20th century won’t cut it.

People aren’t great at assessing heat risk, but they are pretty good at worrying about how much money running the AC will cost them. Sometimes, that means people who die or are injured by heat are people who have air conditioning at home. They just don’t turn it on until it’s too late, because they’re so afraid of getting hit with a utility bill they can’t pay.

The financial impact of running the AC will hit poor people even harder as climate change acclerates. A 2020 study estimated that households in temperate, industrialized countries spent between 35% to 42% more money on electricity when they adopted air conditioning, contributing to “energy poverty,” where people are forced to spend greater amounts of their income to keep thier homes liveable.

We need to find ways to help poorer people pay for air conditioning, just like we have programs that help people pay for heating.

“Can’t people just use good old-fashioned fans to survive heat waves, instead of running the air conditioner?”

Unfortunately, electric fans aren’t an adequate substitute for air conditioning. While fans can help people feel cooler when it’s not too hot outside, a literature review found that electric fans can actually increase a person’s core body heat if temperatures outside exceed 95 degree Fahrenheit.

Another recent study found that when it comes to fans, the type of heat matters a lot. Fans are particularly dangerous when conditions are hot and dry - but they’re considerably better at helping people cool down in hot, humid weather.

That’s because fans cool us down by making our sweat evaporate more quickly, which causes our bodies to shed more water. Shedding water isn’t a problem in sticky, swamp-like conditions, but can be exceptionally dangerous in hot and dry climates.

Who’s most at risk of dying during a heat wave?

Here’s one reason that well-off people rarely think about heat deaths: they largely happen to people with little power.

A 2009 study on an Australian heat wave found that people who lived alone and who had chronic heart disease were in particular danger. A literature review from 2007 found that people who didn’t leave home daily, couldn’t care for themselves, and who were confined to bed were at the most risk - and psychiatric illness put people at a three times grater risk of heat death, even more so than cardiovascular or pulmonary issues. A Korean study found that social isolation and heat risk was particularly pronounced in men.

An earlier study looking at data from the 1999 Chicago heat wave came to similar conclusions: the strongest risk factors for heat death were “living alone” and “not leaving home daily.” However, living alone doesn’t meant that these people were hermits or shut-ins. Disturbingly, over half of the people who perished during that heat wave were “seen or spoken to on the day of or day before their deaths.”

Age is another key risk factor: multiple studies have demonstrated that people older than 60 are at particular risk of death from heat. That also applies to infants and small children, as a kid’s body temperature can rise three to five times faster than an adult’s can.

Race and wealth matter too. A number of studies have found that poorer people, non-white people, and people with less education are at greater risk of injury and death from heat. Safety and crime - or at least, how safe from crime people percieve themselves to be - are also surprisingly potent factors. Research from both the US and Australia has found that, during heat waves, some people report being too afraid to open their windows, or to travel to cooler locations.

I wonder how much this impacts the kind of isolated, older person who watches a lot of US right-wing media, which dedicates vast amounts of air time to fearmongering nonsense about crime.

I also wonder how much of an impact the pandemic has had on heat deaths: social distancing is a vital means of protecting the vulnerable from Covid, but may also put them at greater risk during a heat wave. (And can you blame people for being reluctant to go to a public cooling center during a global pandemic?)

Meanwhile, two factors prove to be consistently protective against multiple studies in multiple places: AC access and social connections. The Chicago study I linked to above found that a “working air conditioner is the strongest protective factor against heat-related death.”

Programs that fight heat deaths by actively trying to reach out to socially isolated people have been successful, like a recent effort in Rome where program workers sought out older people and made an effort to check up on them when it became dangerously hot. In the US, we should be rolling out more programs just like it.

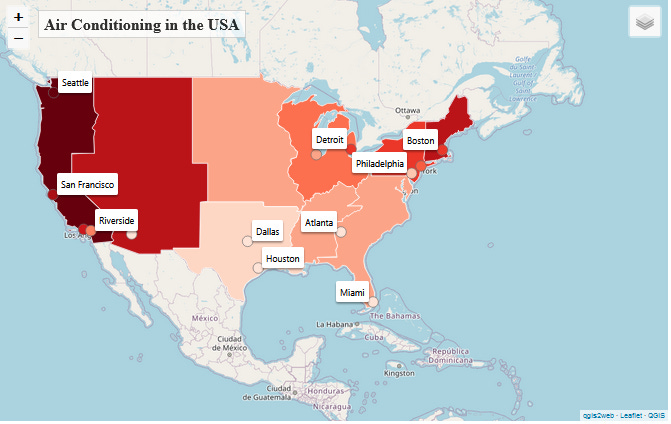

While an estimated 92% of US households have access to air conditioning of some kind, we cool our homes in remarkably different ways depending on where we live.

You can explore these difference in an interactive map I made at this link. I’ve also written about this in the past. But here’s a brief refresher.

Homes in the historically cooler New England, Mountain, and Pacific regions (as defined by American Housing Survey data) are slightly less likely to have air conditioning than other US regions. Meanwhile, Midwestern and Southern regions of the country have AC adoption rates hovering around 98%.

We see much bigger differences when it comes to how people cool their homes. In New England, 55% of homes use room AC (presumably of the window-mounted variety). Just 9% of people in the South Atlantic region, which includes Florida, rely upon individual units: the vast majority rely upon central air conditioning.

These differences in method matter, too.

If your apartment comes with central air conditioning, it’s usually considered to be part of the existing lease agreement. In the US, that gives you more right to demand that your landlord fix it - or let you run it at all - than you might have if you had to purchase a window air conditioner unit yourself.

Meanwhile, most apartment-dwellers with window units - if they’re allowed to use them at all, which many landlords prevent - have to go out and buy the damn thing, schelp it home, and install it themselves. Then, they’ll likely need to do it again when winter approaches, especially if they live in a climate with cold winters.

This constant cycle of removing air conditioners and putting them back in the window again is an awkward and unpleasant task for young, strong, healthy adults. What about elderly people, disabled people, and everyone else who isn’t up to the task of wrestling a sharp-edged 50 pound box into a window in such a way that it doesn’t fall onto either their toes or onto the sidewalk?

They’d better hope that they can afford a professional installation, or know someone who can help. And you can see the obvious problem here, if you recall that socially isolated, poor people are at great risk of dying from heat.

Much as I personally hate dealing with them, window units aren’t all bad. They’re vastly better than nothing, and they might be the most energy efficient way for someone to heat just a single room or two of their apartment.

But really, we should all come together and demand that landlords install heat pumps in their properties instead.

Death and injury aren’t the only outcomes we should measure when we consider the value of air conditioning. A 2020 study found that high heat during school days in the summer measurably harms student’s PSAT scores. However, schools with air conditioning systems saw just 1/5th as much of a reduction in performance than un-air-conditioned schools did.

This all looks even worse when we consider how many US schools don’t have air conditioning. Schools in majority Black and Latino neighborhoods are less likely to have AC than white schools are, an inequity that may contribute to racial achievement gaps.

Many school buildings were built in a world where it was assumed that children would only occupy them from May to September, and that those months would be tolerably cool. That’s no longer the world we live in.

Legal protections for workers around heat are largely lousy across the US - and people who work indoors are often ignored. The Northwestern heat wave in 2021 got people discussing dangers to outdoor workers, but these conversations sometimes ignore the danger to indoor workers.

Low-paid workers in kitchens, meat-packing facilities, factories, and other locations are also in serious danger during major heat waves, as they perform hard physical labor in sweltering, close conditions. Consider, if you will, how you’d feel about spending 12 hours standing over a deep-fat-frier on a day where temperatures hit 114.

This October 2021 story in the LA Times describes the hellish conditions that Amazon workers inside a largely non-air-conditioned Mojave desert warehouse must face.

In California, the state does have has laws requiring breaks, shade, and water for laborers who work outdoors. However, although California’s OSHA was legally mandated to create similar regulations for indoor laborers by 2019, workers are still waiting for the rules to be released.

The federal government is considering issuing nationwide regulations that would protect workers from heath deaths and injury. Hopefully, both indoor and outdoor workers will be accounted for.

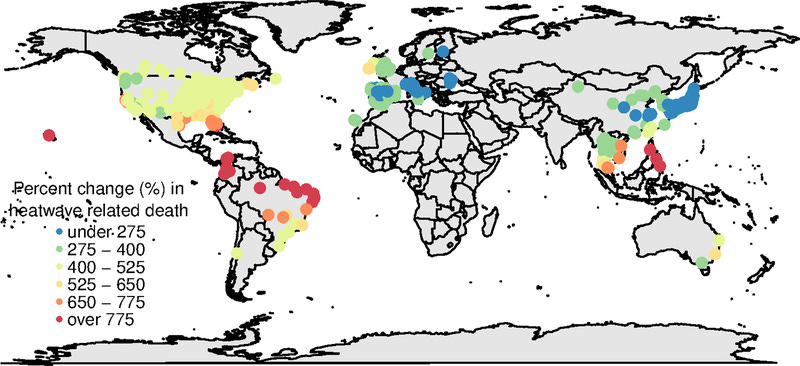

Heat wave deaths are almost certainly underreported around the world. Medically, it can be challenging to confirm if someone was killed by heat. And there are other motives at play, as well. After all, if heat deaths aren’t offiically reported, people in power are less expected to do anything about them.

Consider India, where data journalism outlet IndiaSpend states that heat-stroke deaths must be medically certified to offically count. That’s a figure that may account for only 10% of the actual death toll. In some Indian states, heat stroke victim’s families are compensated, giving authorities a rather clear ulterior motive for making sure that heat deaths are defined as narrowly as possible.

Or look at (once again) California, where a 2021 LA Times investigation concluded that the actual death toll from heat exposure is likely six times higher than the offical state tally of 599 fatalities from 2010 to 2019. What’s more, the data they collected showed “heat-related hospital visits increasing in some parts of California, including Los Angeles County, for at least the last 15 years.”

Thus concludes this assortment of air conditioning factoids. Maybe I’ll write a book on this someday. After I finish the one about drones. Sadly, I think heat deaths and air conditioning are going to stay pretty topical.