The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Tower-Jumpers and Hungry Eagles

To get to drones, we needed to learn to fly first. And throughout the generations upon generations that were required to get humanity into the air, that process often involved a lot of very hands-on experimentation. Earlier in this series, I discussed the tragic fate of the French tailor Franz Reichelt, who died in 1912 after testing his home-made wingsuit by means of jumping off the Eiffel Tower. But he was proceeded in this well-meaning and ill-fated experiment by many others.

Throughout history, numerous people with similar aerial interests to Reichelt pursued experiments in wing-based human flight, appearing in stories that seem to be at least a little bit more historically well-attested than the almost certainly mythological attempts of Icarus, Wayland the Smith and Bladud, which I covered in the last entry in this series. And I write this with intense emphasis on the "little bit," as pretty much all of the stories I will relate here have minimal to no convincing historical evidence to accompany them.

And yet, at least in my opinion, the actual veracity of these stories of human flight matters a lot less than the fact that a number of writers of the distant past felt that it was important and interesting to tell them. Taken at face value, these stories of bird-men are intriguing descriptions of a fraternity of adventurers imbued with both admirable curiosity and minimal self preservation instincts - weird little guys who (mostly) voluntarily constructed artificial wings, flung themselves off tall buildings in front of crowds of jeering spectators, and suffered the consequences therein, be they broken bones, death, or mere crippling embarrassment.

No, these flights may not have actually happened, or may not have happened in the way in which they are described. But I believe that they still have something interesting to say about the deep-rooted nature of the human dream of slipping the surly bonds of earth, one way or another.

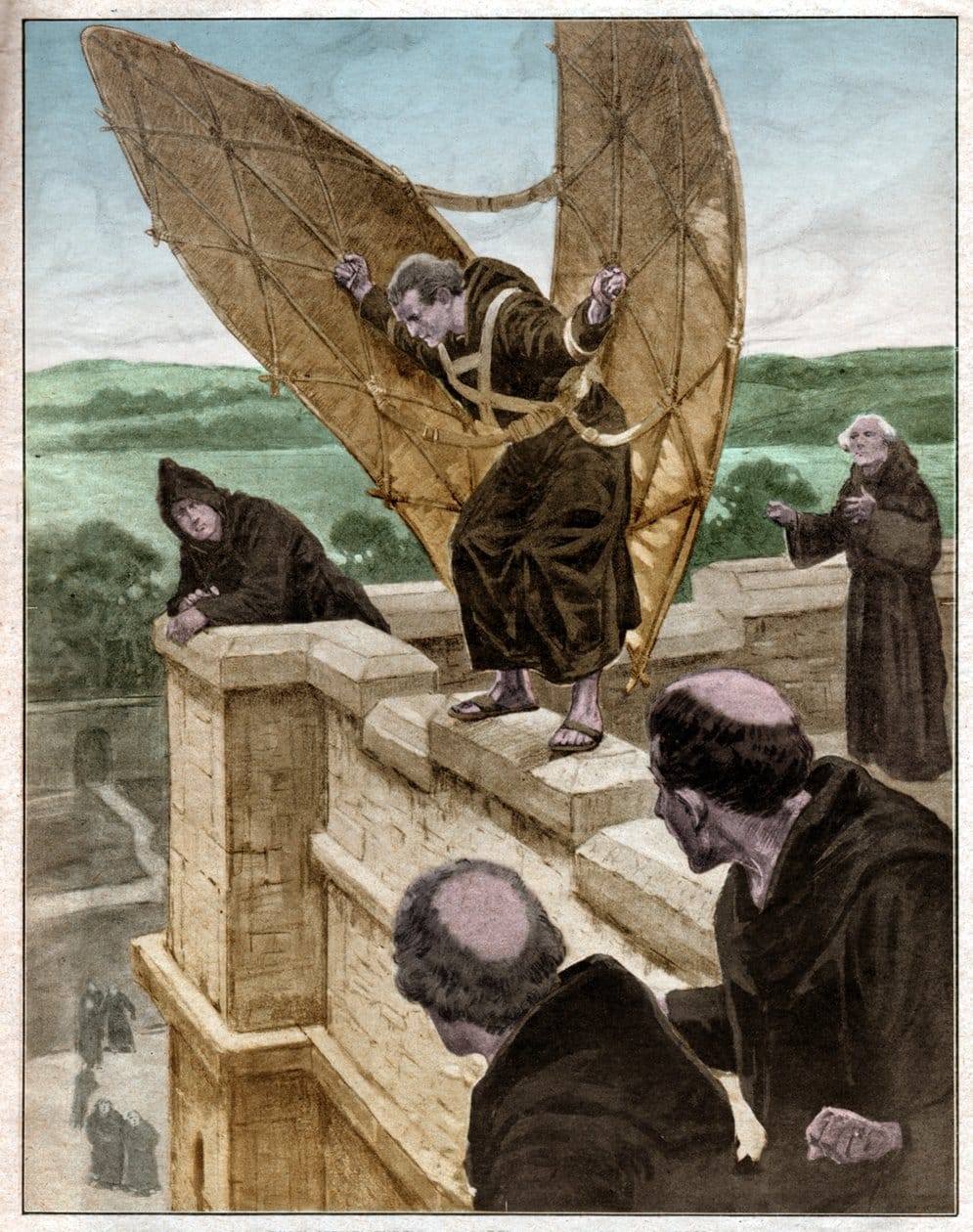

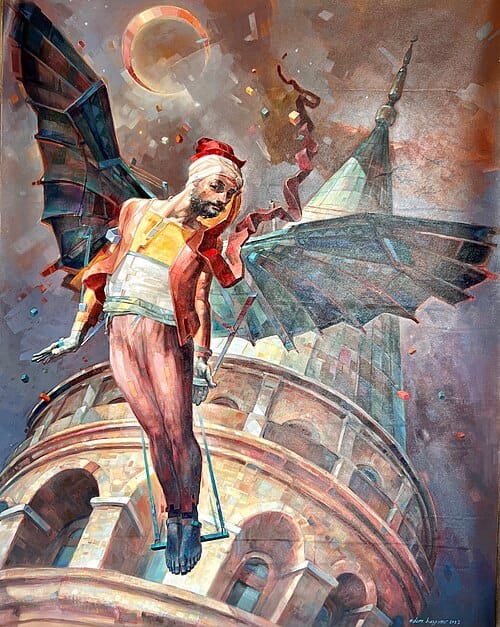

two portrayals of Eilmer the Flying Monk and a fabulous recent painting of Hezârfen Ahmed Çelebi by Adem Başpınar

One such aerial luminary was the monk Eilmer of Malesbury, who is said to have lived sometime between 980 and 1066. We know about him thanks to the medieval historian William of Malmesbury, who wrote in 1125 that Eilmer was famous for two things: accurately predicting the Norman invasion of England in 1066 on the basis of the second appearance of Halley's Comet during his lifetime, and his youthful experiments with aviation.

"He was a man learned for those times, of ripe old age, and in his early youth had hazarded a deed of remarkable boldness. He had by some means, I scarcely know what, fastened wings to his hands and feet so that, mistaking fable for truth, he might fly like Daedalus, and, collecting the breeze upon the summit of a tower, flew for more than a furlong [201 metres]. But agitated by the violence of the wind and the swirling of air, as well as by the awareness of his rash attempt, he fell, broke both his legs and was lame ever after. He used to relate as the cause of his failure, his forgetting to provide himself a tail."

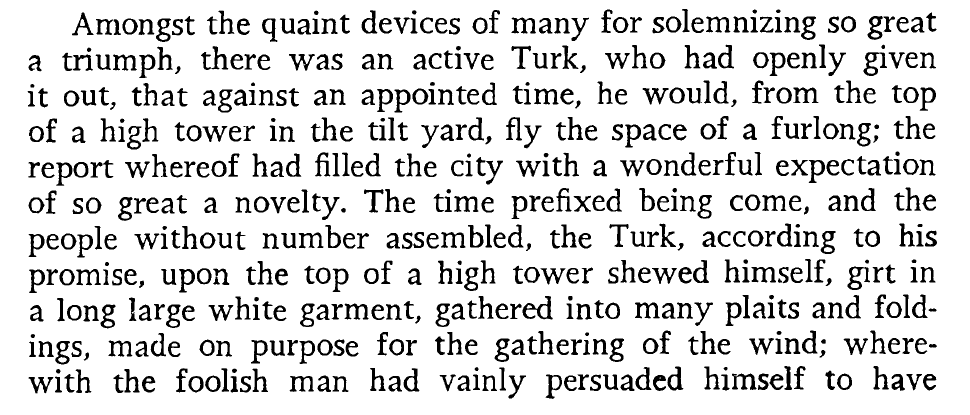

Considerably less successful was an unnamed and unfortunate Turkish man who attempted to fly from a tower in Constantinople in 1162, as described by the English historian Richard Knolles in his 1603 "The Generall Historie of the Turkes":

Centuries later, an Ottoman scholar named Hezârfen Ahmed Çelebi reportedly executed a far more successful flight in 1632 , when he leapt from the 219-foot-height of the famous Galata Tower, and allegedly managed to fly about 3.6 kilometers on the southwestern wind until he landed, unharmed, at a square in the Doğancılar neighborhood.

Impressive as this feat of un-powered flight was - which inherently would have involved crossing the mighty Bosporus strait that divides Europe and Asia - it certainly did not win Celebi any fame, fortune, or favor, at least according to his contemporary and the sole chronicler of his achievement, the (unrelated) writer and traveler Evliya Çelebi:

Another aerial innovator who came to a particularly embarrassing end was a 16th century Italian clockmaker residing in France named Denis Bolori, who - per a story related by an intriguingly disrespectful relative, among other sources validated by the famous early French aviator Léon Darsonval - spent all his non-clock-related free-time developing a pair of wings that were operated by a clever series of springs. [[1]]

In his hometown of Troyes, Bolori culminated his experiments by flinging himself off the Gothic tower of the Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul. He then managed to glide a few kilometers until he came to a fatal crash-landing in the secluded fields of the entirely female Priory of Foissy.

Perhaps the most roundly successful of these historical birdmen was the revered Andalusian polymath Abbas ibn Firnas, who lived in the Emirate of Córdoba in what is now modern-day Spain during the 800s. According to a relatively recently re-discovered 10th century account of his life by the historian Ibn Hayyan, his flight experiments went something like this:

[‘Abbas Ibn Firnas] was so full of ingenuity, creativity, originality and resourcefulness that he was attributed with the knowledge of magic and alchemy, and was often challenged on religious grounds. Some sheikhs said that he managed to launch himself into flight. He clothed himself in feathers [fastened to light colored] silk and spread for himself (madda) two wings of calculated structure, with which he was able to rise in the air. He flew from the vicinity of Rusafa, moved through the air and then circled until he landed in a place far away from where he departed. But this landing went poorly when he hurt his tailbone. He had not managed the landing very well. He did not take into account that a bird, when landing, does so on its tailhead, which he [neglected].

This, then, is a major achievement in the annals of human flight: a man who flew like a bird, and suffered nothing more in the process than a nasty bump on the hindquarters.

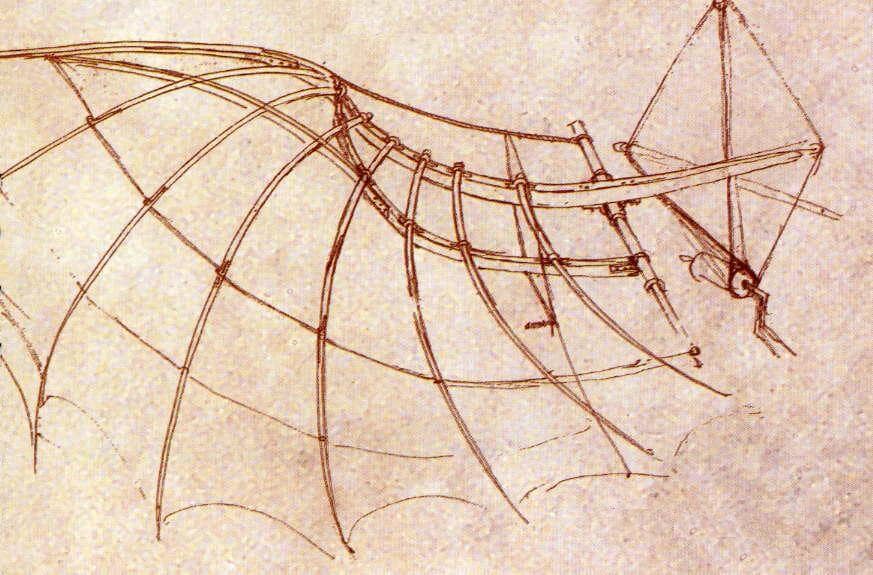

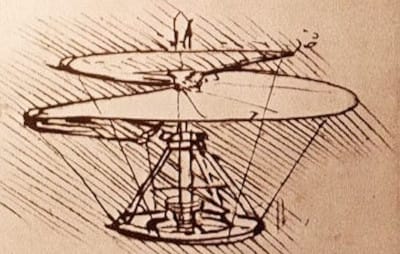

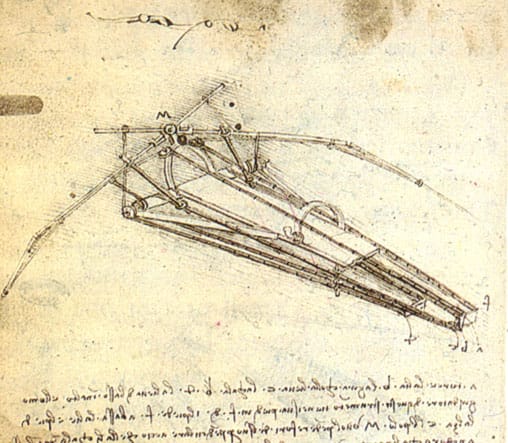

Some of Leonardo da Vinci's aerially-inclined drawings.

Unsurprisingly, nobody appears to have made a more technically-credible, albeit entirely theoretical, attempt at winged human flight than Leonardo da Vinci.

The esteemed scholar, artist and launcher of a gazillion special traveling museum exhibits was the most prolific scholar of bird (and bat) flight in known history before the 19th century, devoting an obsessive amount of time to observing these animal's graceful movements in the air.

Unlike the vast majority of other early aerial experimenters, da Vinci quickly recognized that the human body simply isn't designed in a way that would allow us to merely strap some wings to our arms and take off in the same fashion as a bird or a bat, as so many others had incorrectly assumed. (The Italian mathematician and early biomechanics specialist Giovanni Alphonso Borelli would later decisively prove this dreary biological reality in his 1680 treatise "De Motu Animalium"). Therefore, da Vinci devoted his time to constructing a far more airplane-like lifting body, which a human pilot could then operate via a series of various pulleys, levers, and pedals.

The articulated wings of his ornithopter design were very much based on these biological observations, with an obvious visual bat-like quality. While it's clear that this design could never actually have functioned as intended, it was still closer to the mark than any other known, prior flying machine design, and it had a considerable influence on many subsequent generations of aviation engineers. Most importantly of all, Leonardo never actually attempted to fly in the device himself, which is excellent evidence that da Vinci really was as smart as his historical reputation makes him out to be.

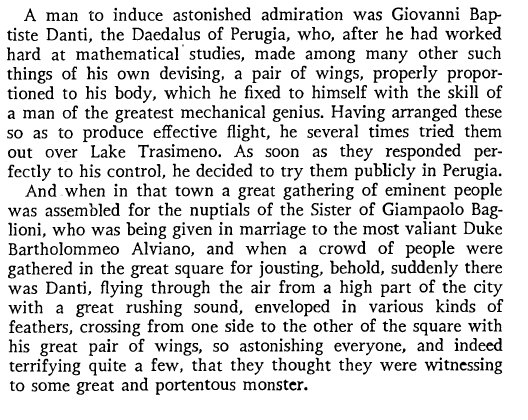

Reportedly, one of Leonardo's Renaissance contemporaries actually did attempt a flight with artificial wings - and while his aborted effort to crash a wedding by means of mechanical wings was not exactly a success, Giovanni Baptiste Danti did at least survive to tell the tale. Per a 1652 account by Cesare Alessi, writing generations after the actual event:

the story of Giovanni Danti

These are just a few selected accounts among many other historical stories of men who were hell-bent on figuring out how to achieve human flight by mechanical means, and who were willing to put their own eminently breakable bodies on the line to prove a technical point. Doomed as their efforts all were from the beginning, it is impressive that there are still so many of them - especially because these birdmen are just the ones we know about, members of a tradition that doubtless included numerous other long-forgotten eccentrics, dinguses, and terminal optimists. Despite myself, I see something inspiring in the total, and totally senseless, conviction that these men had in their cause, and in the eventual conquest of the air by human ingenuity.

It is so often the case that it takes a real chucklefuck to break the trail that eventually and tortorously leads to genuine human innovation, and so it was with birdmen and aviation. By means of proving that human beings cannot readily fly by strapping wings to their arms and jumping off stuff while people below say rather unkind things about them, they inspired other thinkers to pursue the more productive path of flying machines. And eventually, that would be how we got drones, satellites, and bargain-basement flights on EasyJet, among other wonders of the modern world.

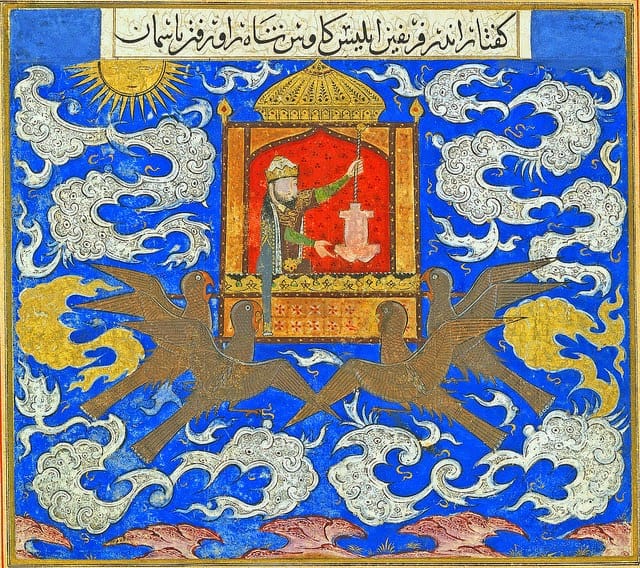

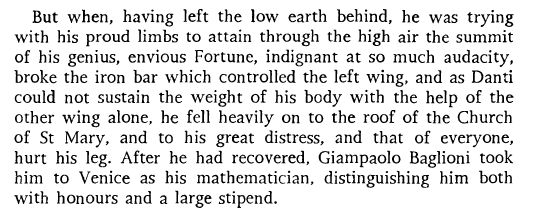

1420 illustration of Alexander's flying machine, a Byzantine mosiac of Alexander the Great, a 13th century German miniature painting of the griffon-machine-theme

The Agony and the Ecstasy of Eagle-Powered Flight

While Alexander the Great only made it to his early 30s, succumbing prematurely to some sort of mysterious malady that could have been anything from good old-fashioned poisoning to a bout of malaria, he managed to accomplish an awful lot of rampaging, conquering, and terrorizing in that brief time span.

One would assume that all that frantic empire-building activity would have left Alexander with little free time to pursue his hobbies (do you think he'd have been into painting Warhammer miniatures?) - and yet, according to the reams of fan-fiction that has produced about him ever since his death, this wasn't the case. Indeed, if we take these antique transformative works at face value, Alexander somehow managed to find the time to come up with a bunch of cutting-edge mechanisms. [[2]]

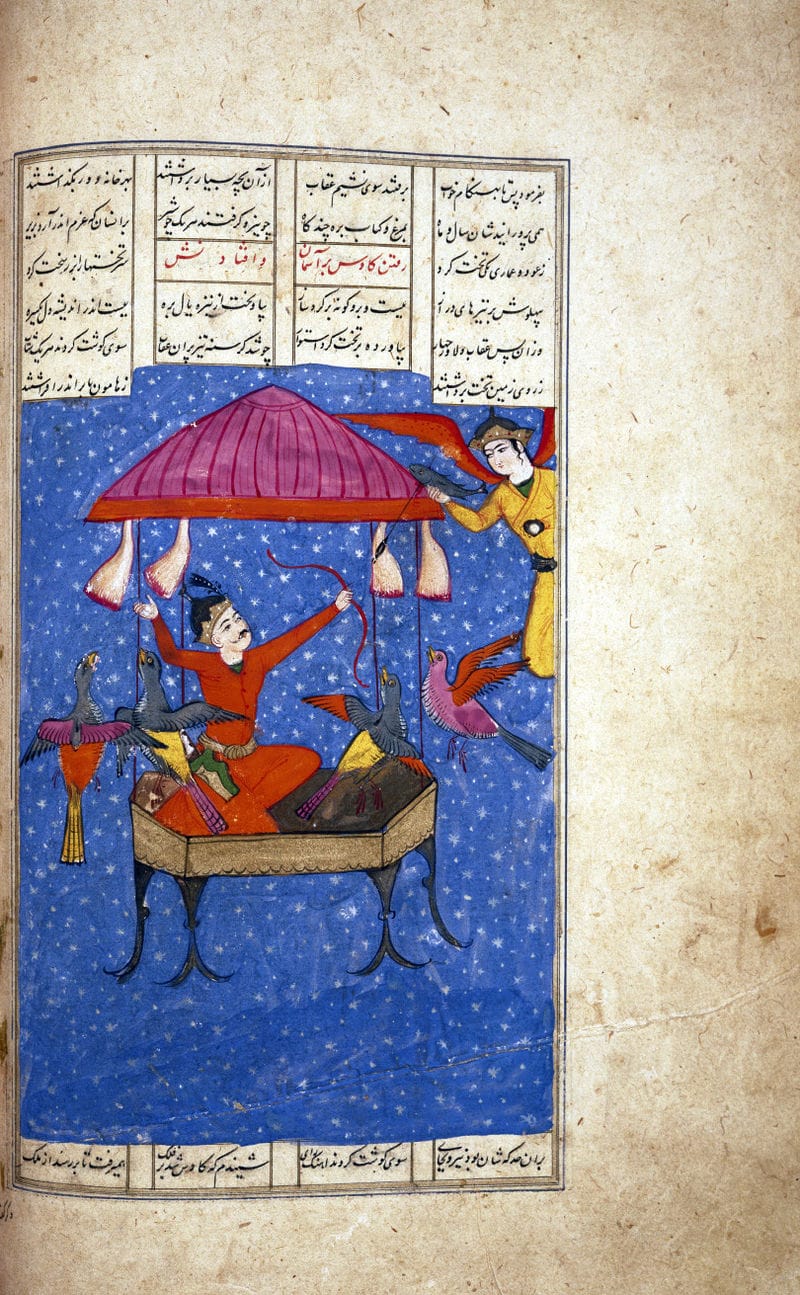

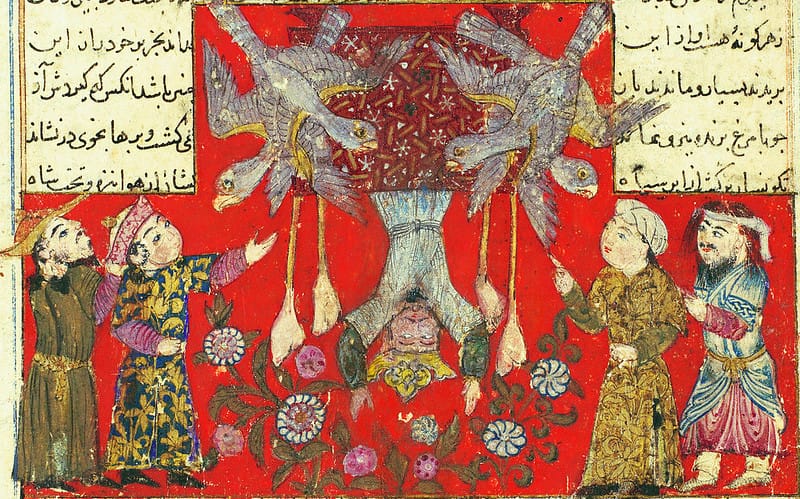

These included, supposedly, a flying throne powered by hungry eagles. Per this legend, Alexander hit upon a method by which he might attach four starved griffins, or maybe just some regular eagles, to each side of a rectangular carriage. To alight into the air, he would then skewer some fresh meat on a stick and hold it just over the bird's heads, inducing them to spring into the air, taking the carriage along with them.

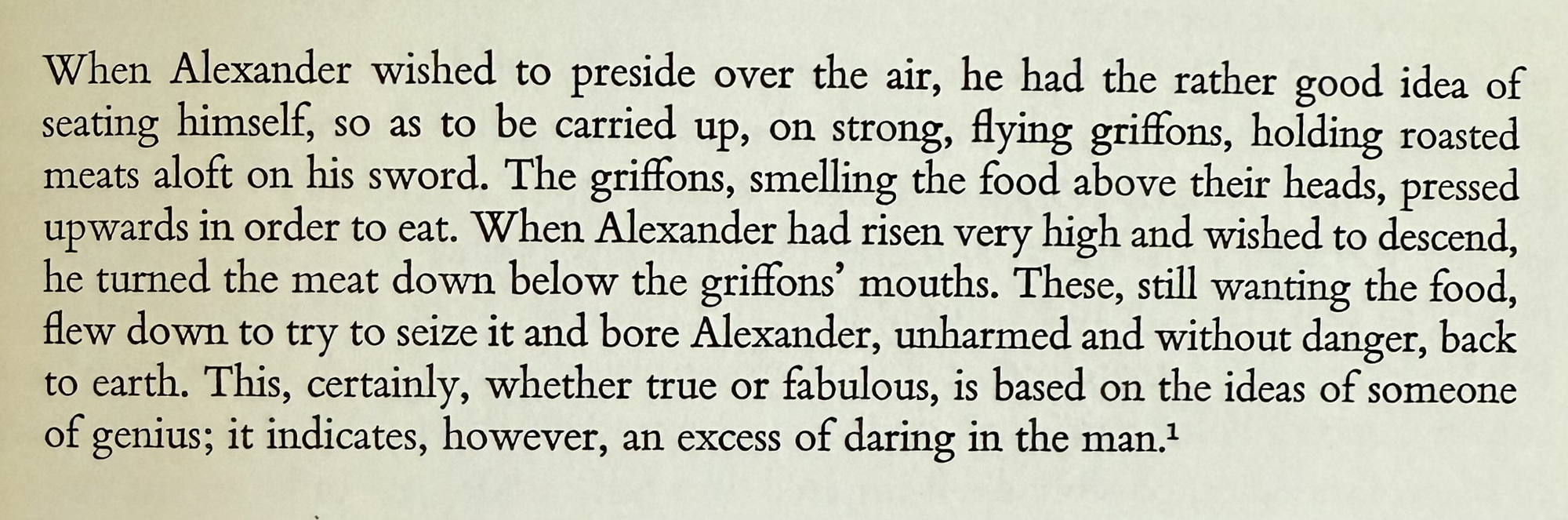

In a version of this story written by the 15th-century Italian engineer Giovanni da Fontana (who we shall hear from again later in this series), we are even given an explanation of how the hell Alexander got down again:

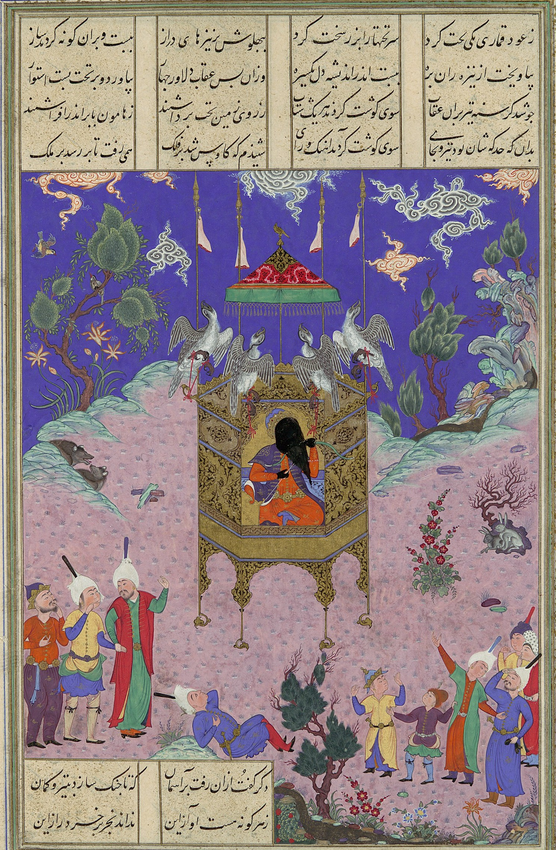

An intriguingly similar version of this eagle-powered imperial aircraft appears in the Persian Shahnameh (“Book of Kings”), which I mentioned previously in an earlier entry in this series. As the story goes, the powerful, arrogant, and chronically foolhardy Iranian ruler Kay Kāvus was out hunting when he was approached by a handsome youth, bearing a bouquet of flowers. The silver-tongued youth complimented him on his glorious reign, and insisted that its wonder would never fade if Kāvus could just conquer one more place:

The sun still keeps its secrets from you; how it turns in the heavens, and who it is that controls the journeys of the moon and the succession of night and day, these are as yet unknown to you.

Unsurprisingly, the youth was a demon in disguise, and since Kāvus was not overly-endowed with either self-preservation instinct or humility, he fell for its evil ruse. And so he set up about building a flying machine at once, along similar lines to the contraption attributed to Alexander.

various versions of Kay Kāvus having a worse time than he'd initially bargained for

First, he captured some unfortunate eaglets and reared them to be "strong as lions," and then he harnessed his eagle-children to a mighty throne made of and of gold, upon which he affixed kebabs made of raw meat to each corner. Just as in the Alexander tale, the eagles launched Kāvus and his throne swiftly into the sky, all the way to the “sphere of the angles," and per the narrative, he may have even “fought with his arrows against the sky itself.”

Fun as this all might have been for a narcissistic king, the eagles grew tired, and it was then that Kāvus realized he had not bothered to teach them a command that might compel them to descend. (Characteristically, he had not figured out Alexander's trick). Eventually, the eagles grew so exhausted that they could fly no longer, and both the birds and one now deeply regretful man tumbled to the earth, right into a nice big thicket filled with sharp thorns.

Luckily for Kay Kāvus, he is rescued - "once again," as the Dick Davis translation of the source material snarkily emphasizes - by a group of far more steadfast and honorable rescuers. It is also made very clear that these heroes have had it up to here with Kay Kāvus's kooky-ass shit, even if he does happen to be a king:

Suitably chastened, Kāvus finally turns to a life of prayer, virtue, and charity to the poor, and never does anything as dumb as eagle-fueled flight again. If only more of our modern crop of reckless oligarchs could have such productive misadventures.

It is unclear where exactly the idea of an eagle-powered aircraft came from exactly, but it appears to have been rattling around in the collective imagination of theworld for quite a long time, a medieval Just One Weird Trick meme ascribed to various historically-improbable sources. Did someone ever actually try it? We don't know, and we probably can't know, but part of me does desperately hope that some understimulated Middle Ages goofball actually did burn a few years of effort on strapping pissed-off birds of prey to four sides of a relatively light-weight throne. This too, is the spirit of human innovation.

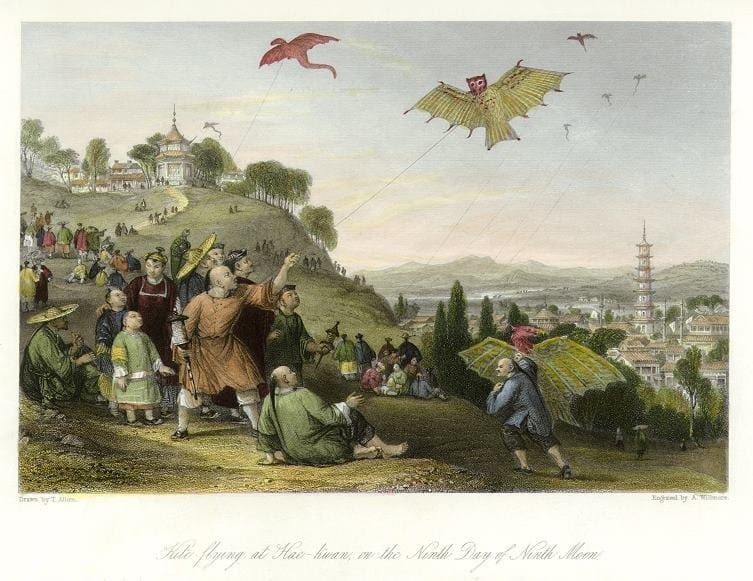

a man-lifting kite in use in 1918, the man-lifting kites of Samuel F. Cody, and an old print of Chinese kites.

Man-Lifting Kites

From our jaded modern perspective, it is nearly impossible to imagine how completely insane it must have been to read "The Travels of Marco Polo" as a Western European in the 1300s. For the very first time, many astounded denizens of the Occident were hearing about crocodiles, paper money, coconuts, and complex postal service systems, among many other exotic and previously-little-known revelations. Imagine how you'd feel if you were hearing about giant lizards that can eat people that reside in innocent looking bodies of water for the first time.

And so, amidst all the other novel concepts that pour out of the pages of Polo's "Travels," it's easy to miss an intriguing little section where he claims that Chinese sailors would attach drunkards to man-lifting kites as a form of weather prediction:

Both the kites themselves and their ability to lift a guy into the air must have been major novelties to European audiences, as kite technology appears to have originated in Asia far before it reached the West around the 14th and 15th centuries. By the time Marco Polo came along, the Chinese had already been constructing and flying kites since at least the Warring States period, a practice that almost certainly dates back much further than even that in reality. Chinese history contains a number of interesting stories that involve the relationship between people, kites, and kite-like objects.

One of the earliest examples of a device that sounds a little like a person-lifting parachute or kite concerns the legendary Emperor Shun, who is said to have lived from 2258 BC to 2208 BC. According to an account written in the late 2nd and early 1st century BCE by the Han Dynasty historian Sima Qian, Shun began his life inauspiciously as a wandering but good-hearted orphan, booted out of his house by an evil stepmother. His remarkable purity of heart eventually came to the attention of the morally upright Emperor Yao, who had been cursed with nine shiftless sons and no clear means of appointing a (male) successor.

The Emperor therefore decreed that Shun would marry both of his impressively-named daughters, Ehuang (Fairy Radiance) and Nüying (Maiden Bloom): not stopping there, he also awarded Shun administrative control of a small district. The sisters Ehuang and Nüying had learned to fly like a bird for reasons that no one seems to have bothered to elaborate on, and they duly taught this skill to their new husband.

Mastering the art of flight would end up coming in handy for Shun, because his evil stepmother and useless father both became jealous of his success. Naturally, they decided to deal with their complex feelings about their stepson by trying to kill him.

To accomplish this, Shun's lousy family tricked him into ascending to the very top of a barn or a granary and then lit it on fire while yanking the ladder away, assuming he would be burned up in the flames. Thinking quickly, he recalled the flight training that his wives had given him instead. And thus, he took two reed hats, which were pretty conveniently within easy reach, and used them as a parachute, a trick which allowed him to land on the ground unharmed. And so he and his flying wives lived happily ever after.

Considerably later in history, the notorious Japanese thief Kakinoki Kinsuke in the 1700s - or maybe it was Ishikawa Goemon in the 1500s, the sources are maddeningly unclear - is said to have used a man-lifting kite to steal valuable golden scales from ornamental fish mounted to the roof of Nagoya Castle.

Samuel Franklin Cody's man-lifting kite, Pocock's kite-drawn carriage, and a genuinely classic example of the "so easy even a woman can do it!" motif in publicity for new technological innovations.

By the 1800s, the British schoolteacher and Methodist leader George Pocock knocked together a design for a man-lifting kite that he had so much faith in that he decided to test it with his own children, at one point elevating his daughter over 270 feet in the air, and at another, flying his son to the top of a 200 foot cliff in the vicinity of Bristol. Luckily, both children managed to survive this process of kinetic experimentation, and Pocock went on to develop a terrestrial but reasonably effective kite-drawn carriage that he dubbed the Charvolant, which saw a certain amount of real world use.

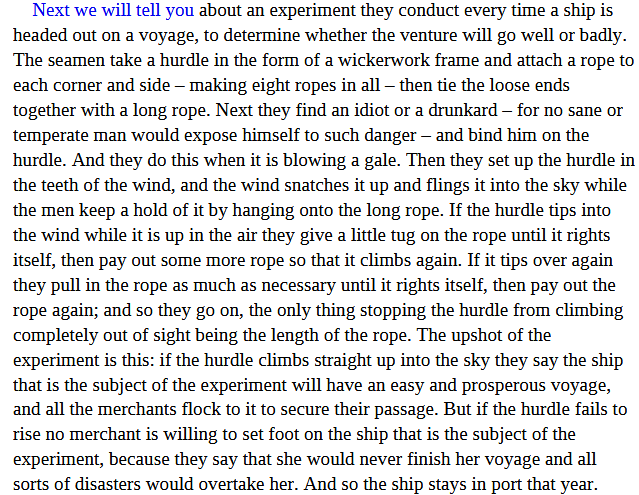

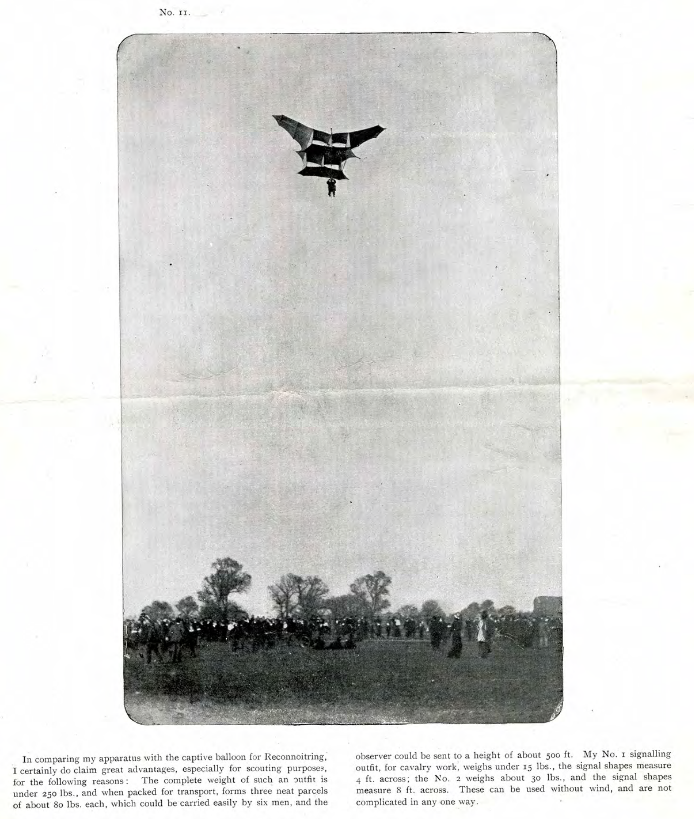

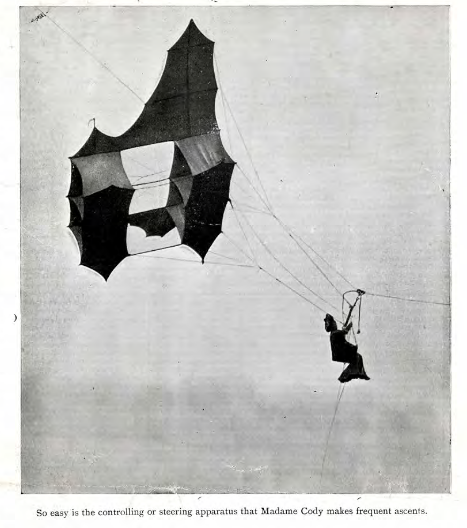

From this point onwards, a number of other experimenters would tinker with man-lifting kites for purposes of both scientific exploration and wartime intelligence gathering. These luminaries inclued the Wild West showman and aviation enthusiast Samuel Franklin Cody (not to be confused with Buffalo Bill), who managed to lift a brave passenger up to 1,600 feet on one such contraption.

However, these new innovations in man-lifting kites happened to overlap all too closely with the Wright Brother's first flight in 1903, and they were cast aside largely as curiosities in favor of the heavier-than-air flying machines that dominate the skies today. Their wind-borne legacy lives on in the Xtreme Sports form of kiteboarding, another curious evolutionary off-branch from the progression that would eventually lead us to modern passenger jets, satellites, and (of course) drones.

Next time, we're talking about exploding kites, scary dragon-shaped balloons, and other early efforts that approximated the unmanned flight we've all known to come and love, or alternately fear, today. Smash that Ghost subscribe button today, and I'll see you soon.

[[1]]: If there is one universal theme I've picked up on in my study of the history of technology, it's that engineers and tinkerers just love to extrapolate their area of expertise to other fields, often with disastrous results - a problem that is still very much with us today.

[[2]]: Alexander the Great probably didn't see flying saucers on the battlefield though, despite what Buzzfeed and the History Channel may have led you to believe.

Here are past entries in this series:

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Preface

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: A Drone of The Mind

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Forgotten Technologies, Towers, and Roman Shitposting

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Death Rays, Brass Horses, and Dragon-Surprising Mirrors

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Pondering Orbs, Black Mirrors, and World-Viewing Cups

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: The Fear and Fantasy of Flying