The Ancient History of Drones Explains Why They Freak Us Out Today

Ancient myth and legend has a lot to tell us about the drones of today.

What’s the deal with drones? At first glance, they’re basically glorified remote controlled airplanes with computers and cameras stuck to them: not exactly the kind of thing that you’d expect to quicken the blood or excite the soul of most normal human beings. And yet, ever since the start of the 21st century, drones have collectively fascinated, frightened, and repulsed us.

Drones definitely are compelling.

But why?

The answer to that question is something I’m hoping to explore in a book. But in this piece, I want to look at a key element of that answer: the drone technology of the past. And I don't mean the recent-ish-past of the 2000s, or the hazy and far-off days of the mid-1990s, or the primordial soup (that I have only read about in legend) of the 1980s and 1970s.

No. To understand what the deal with drones is, we need to look to the earliest origins of human society itself.

While drones may seem like the archetypal example of a frighteningly new and unprecedented technology, many of the ideas underpinning drones are actually, to use a technical term, old as hell. While the omnipresent civilian drones of the 2020s are “new” in one sense, in another, they’re simply the culmination of a far longer process.

To invent something, we need to be able to imagine it first. And humanity has spent a very long time imagining being able to do drone-like things. We’ve spent a lot of time speculating on what it might be like to gaze upon the earth from above far beyond the confines of our bodies, o fly through the stratosphere like a bird or a bug, and to craft human-made objects capable of moving on their own accord.

Famous philosophers, practitioners of many shamanic religions, and a likely majority of modern-day humans all share a belief in at least the possibility of a person separating their soul from their physical body. In philosophy, this is called “dualism,” the notion that our bodies and our minds are fundamentally different things.

We understand this stuff viscerally.

How many times have you seen a cartoon or a movie where a person’s “soul” or “ghost” neatly snaps off from their body after they die, then wanders around while looking spooky and translucent - maybe while doling out spiritual advice? Force ghosts in Star Wars. Everything about Casper the Friendly Ghost. That whole bit in the Lion King where Mufasa yells at Simba from a magical cloud. You get the picture.

Or consider the deep weirdness of dreaming. While our bodies are parked in our beds, our brains and (in theory) our souls are imagining flying swan-like above the earth, or, less dramatically, prancing around the office both nude and totally unaware of it. As far as you’re concerned, in that moment, you’re in two places at once.

Examples of this basic concept abound across human cultures, from the writings of Plato - who figured that when good people die, they're promoted to being a roving, disembodied intelligence (sounds nice) - to legends among Irish seamen that claim that storm petrels contain the flitting souls of unfortunate sailors lost at sea.

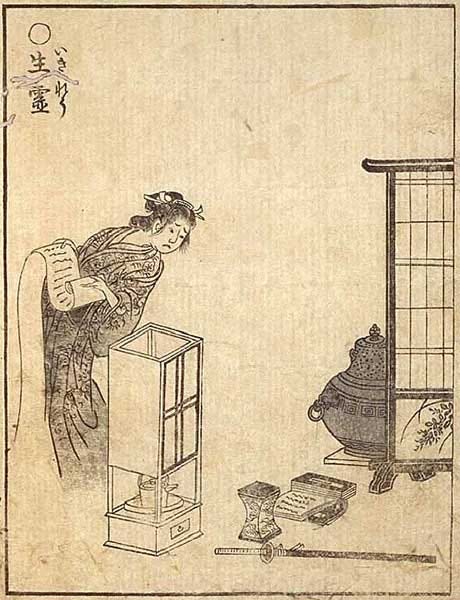

Japanese literature has spoken of something called an Ikiryō or “living ghost” since at least the year 1000, the idea being that a living person (who usually is in a vengeful mood) gains the power to "project" their spirit, allowing them to torment or even kill their enemies from very far away. The practice of “warging” in the Game of Thrones franchise features another direct drone metaphor: Bran uses magic to simultaneously occupy both his own body and that of another animal or person, a secondary vessel he can use to move about the world far from himself.

Some Siberian shamans believe that part of a shaman's own soul can be incarnated within certain animals, which then function as helpers, or as a sort of altar-ego. Today, some of these Siberian traditions extrapolate this soul-belief to modern technology. According to a recent research study, some city-dwellers from Tungus-Manchu cultures in North-eastern Asia and Siberia report that their cars, phones, and laptops occasionally “behave” as if they have been possessed by spirits, just as their ancestors might have assumed that spiritual possession was responsible for, say, the freakish behavior of a local tiger.

“If a spirit settles in a car, that car can go crazy, refuse to work, or run on its own. The technological devices can gain their own will and go not where a human sends them but where they themselves want,” explained one Tungus-Manchu interviewee to a researcher.

In other words, if your car or your computer are acting up, it might be because the spirit it contains is being a real asshole. And can any tech-using human being in 2021 claim they’ve never suspected this is what’s going on when their computer is on the fritz? Drones, with their spooky powers of autonomy, push this suspicion about a machine being up to something to an even greater extent.

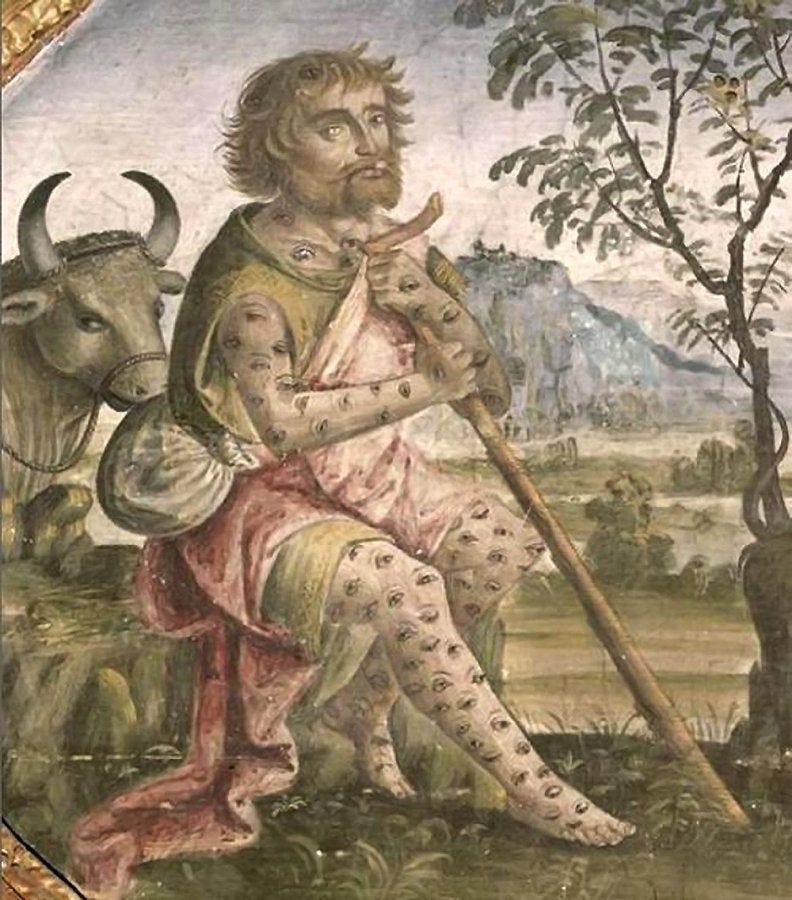

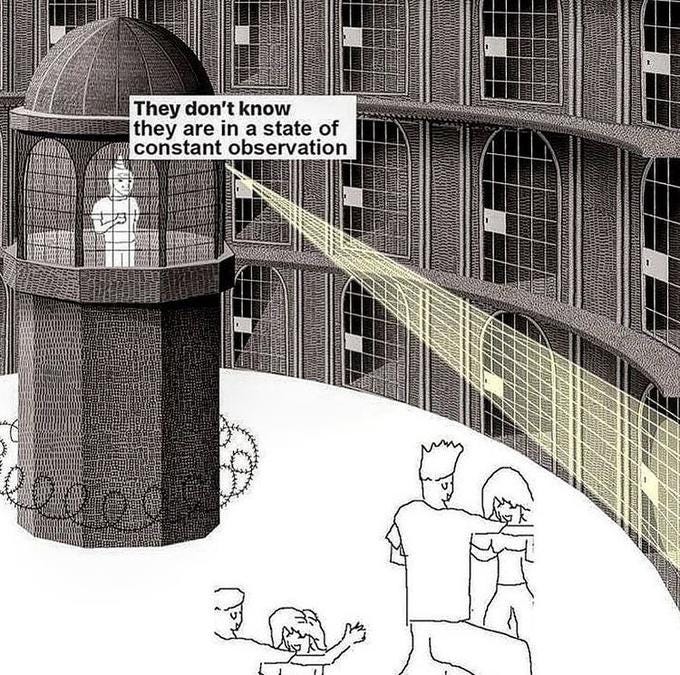

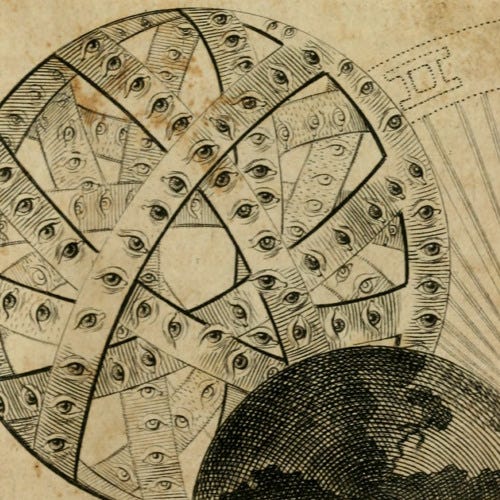

We've also spent many thousands of years contemplating how useful it would be if we could see things from far beyond the reaches of our eyes alone. Consider the ancient Greek god Panoptes, who the goddess Hera granted an unusually large share of eyeballs so she could use him to spy on Zeus, her philandering god-king husband. If that name sounds vaguely familiar, you’re not wrong: philosopher and surveillance-studies pioneer Jeremy Bentham actually named his own “panopticon” prison in Panoptes’ honor.

The Norse people believed that the god Odin deployed his two pet ravens, Hugin and Munin, to traverse the earth in search of intelligence, information they would relate back to him in the evening. Per these long-mysterious lines from the Eddic poem Grímnismá:

Hugin and Munin

Fly every day

Over all the world;

I worry for Hugin

That he might not return,

But I worry more for Munin.

In essence, the ravens were not just talking birds (which is great enough), but also were roving sensors, a means for Odin to gather intelligence from afar without having to go out and do it himself, or place himself in danger of being perceived.

Outside the realm of myth, some scholars believe that ancient ruler’s huge pyramid-mountains and high-up fortresses served not just as a practical means of self defense, but also a means of implied surveillance. Tall edifices made it clear to the people down below that someone they couldn't see was looking at them, a very early expression of the concept that animates our modern fear of being watched by something sophisticated and man-made - like a drone - that we're unable to equally watch back. Bentham exploited this exact deep-rooted human discomfort around not knowing if we’re being watched with his panopticon prison.

Within this historical context, then, the modern drone is merely the latest, freakiest incarnation of these old ambitions and fears.More than just a plastic helicopter, a drone is also a physical object through which our "soul" can explore - or surveill - the world while staying firmly planted on the ground. Many drone pilots, especially drone racers, fly while wearing a “first person view” or FPV headset, which streams video in real-time from a camera mounted on the drone.

FPV flight produces the curious sensation of being both inside the drone and outside of it, controlling the movement of a physical object that is both you and not you: it’s a true mind meld between mind and machine. Via the medium of a drone with a camera stuck on it, the formerly somewhat spiritual, abstract idea of “projecting” ourselves and our actions into the body of another animal or object has moved into the realm of the firmly concrete.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that our species is taking some time to adjust.

Human beings have, too, long had an attitude of both fascination and deep distrust of human-made things that fly. Across cultures and across history, we have long associated the idea of flight with hubris, and with alluring dreams that ultimately prove fatal to mere, fallible human beings. To compound that fear, or perhaps complement it, we have also long feared being attacked or set upon from the sky, pelted with weapons or lightning bolts by enemies that we cannot reach or see.

Myth regularly deals with the fear-of-flying question. While most Westerners know about the unpleasant fate of the ancient Greek Icarus (who flew too close to the sun), fewer know about the misfortunes of the arrogant Persian king Kay Kāvus, who crafted a chair propelled by starved eagles to take him up into the heavens, and ended up coming to rest in a thorn bush after forgetting to teach the eagles the meaning of “down.” Interestingly, a very similar story concerns Alexander the Great, who became the subject of various fanciful tales about his journeys in the Far East - collectively known as the Alexander Romance - not long after his death.

While humanity has long mistrusted flight, that hasn’t stopped inventors from finding new ways to achieve it. According to some antique historians, humanity has been fiddling around with model airplanes for a lot longer than you'd think. Sometime before the year 255 BC, the great civil engineer and inventor Lu Ban (or it might have been the philosopher Mozi) allegedly crafted what may very well be history’s first drone-like object: a wooden bird-shaped kite that supposedly could stay aloft in the air for three entire days. Some have even argued that a carved falcon dating back to 250 BCE, found in an Egyptian tomb, was actually built as a sort of toy glider (though lots of other people think this is bunk, so take it with a grain of salt).

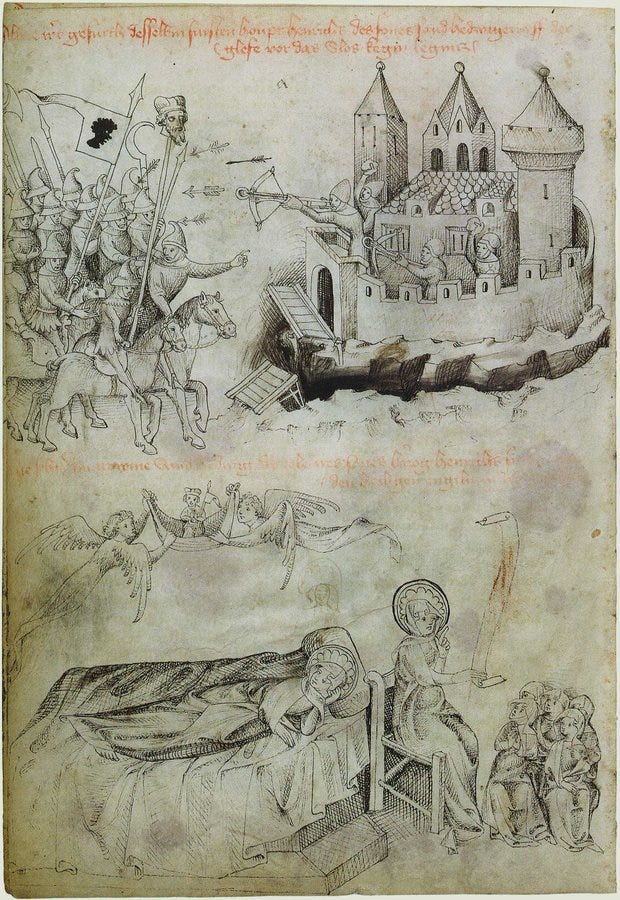

Many hundreds of years later, terrifying dragon and ogre shaped kites were introduced to European sensibilities by the Mongols during their incursions onto the continent in 1200s. The most famous such incident took place at the terrible 1241 Battle of Legnica, where the Mongols reportedly engulfed the Polish armies in noxious smoke, emitted form a banner or a kite that resembled a "hideous, jet-black head with a bearded chin"

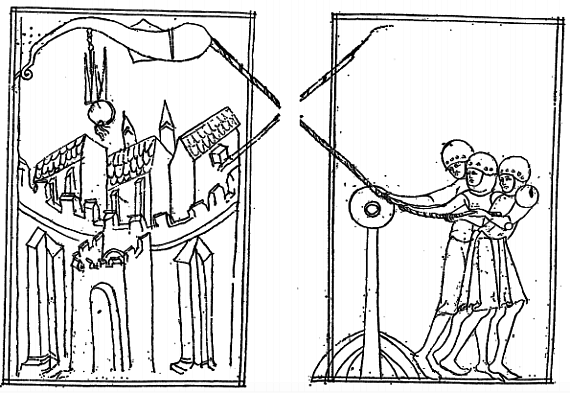

In 1327, Walter De Milemete’s De Nobilitatibus, Sapientiis, et

Prudentiis Regum - a book produced as a gift for the young King Edward the 3rd - depicted soldiers dropping some kind of incendiary substance on their enemies out of a kite that looks a bit like a fish, a device likely based on Mongol designs. In 2008, researchers attempted to build such a device themselves, and deemed it a surprisingly useful and practical military weapon.

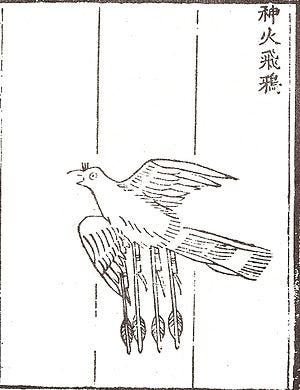

People in China, too, were experimenting with flying explosives by the 1300s. The early Ming Dynasty Huolongjing (Fire Drake/Dragon Manual), an illustrated guide to firearms, includes a picture of a 'divine flying fire crow' (shen huo fei ya), which supposedly functioned as a kind of aerial bomb.

In 1520, one such strange and terrible dragon kite thoroughly terrified the celebrants gathered at the historic meeting of King Henry VIII of England and Francois I of France on the legendary gathering at the Field of the Cloth of Gold. The dragon swam “slowly through the empty ether, rowing with its wings and the assistance of its feet,” terrifying the unsuspecting crowd. To this day, history has yet to figure out exactly what the dragon was, or who was behind it, or why they’d decide to deploy it.

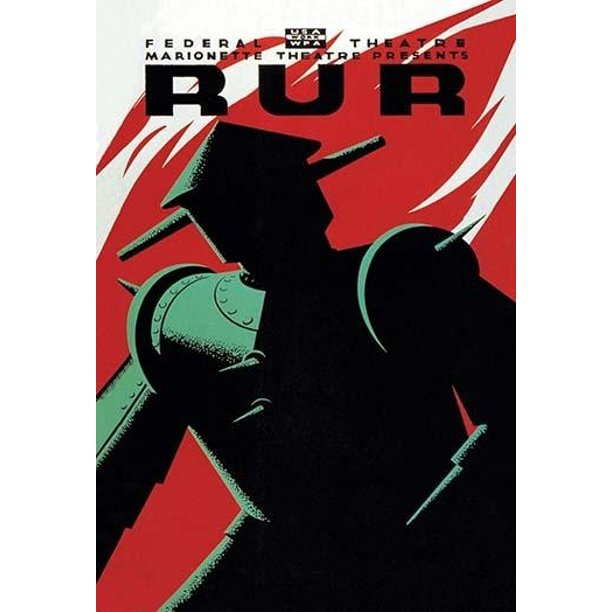

Finally, our species has long been unnerved by the concept of self-moving machines, a technological concept that dates far further back than the 1920 coining of the word “robot” by the Czech playwright Karel Čapek in his strange and futurist play “R.U.R.”

Some Greek myths claim that the terrifying birds sent to rip out the liver of the hero Prometheus on a daily basis (it grew back) were mechanical, with flashing metallic wings. Others claim that the lame Greek blacksmith god, Hephaestus, had invented self-moving machines: some that resembled human men and women, others that could autonomously follow you around and serve you wine. The 1000-year-old Tibetan Epic of Gesar of Ling describes how the child-hero fights off three birds with sword-like iron and copper wings sent to murder him.

Supposedly, some Byzantine emperors over-awed their supplicants by showing off an incredible self-moving throne: as the throne elevated the occupant up towards the ceiling, organs would blare music, mechanical birds would chirp and mechanical lions would roar. The throne may have been inspired by older stories about the throne of King Solomon, a supposedly mechanical marvel that used fake animals to marvelously assist the ruler up the stairs.

Far-sight, flight, and automata: all of these stories and the technological concepts that swirl around them had to unite to create the conditions that allowed the modern drone to exist. Drones did not spring forth fully formed from the forehead of some engineer in a garage. They are part of a tradition, things that exist in context. They inherit a suite of very old and very potent human fears.

Just like our ancestors who feared mysterious threats from the sky, some research shows that modern people are unnerved most by the ambiguity of drones – the fact that drones really don’t make their intentions clear about who sent them or what they are doing. Unlike small consumer drones, manned helicopters and airplanes are often big enough to allow us to see their livery, which gives us a few clues to who controls them.

In many cases, we can also look up a given manned aircraft with an air traffic management website or app: right now, we can’t do the same when we spot an unexpected drone in the sky. Our ancestors might have interpreted the arrival of a mysterious floating apparition as a manifestation of the spiritual world, as a worrisome omen. Today, we may know that a drone is a technological object and (probably) not a vengeful ghost, but that doesn't give us much more information on what a given drone that's hovering in front of our noses is actually up to.

Thankfully, the development of unmanned traffic management systems (UTM) means we may soon enter a future where drones can more readily identify themselves and their intentions to people on the ground.

Just as our ancestors worked to interpret the world around them by naming and understanding the phenomena that surrounded them, these identification systems may make people feel they have somewhat more agency over the drones that fly above their heads - that they are not totally at the mercy of a flying camera, a aerial eye with unclear intentions.

History also helps us better appreciate the many good things about drones, and the advantages they may afford humanity. For the first time in history, people who want to traverse the world from above don’t need to develop remarkable shamanic powers, or to drop many thousands of dollars to learn to fly an actual airplane. If you want to explore the earth from the perspective of a bird – from the perspective of a god! – you can just buy a drone on the Internet.

Perhaps most meaningfully, cheap drones make it far easier for people to make their own maps. Map-makers hold immense power in our societies: if you can make a map, you can set property boundaries, define (or worsen) social problems, and win legal arguments. Small drones have made it vastly easier for people who aren’t professional cartographers or surveyors to enter the cartographic conversation. Our ancestors would probably be impressed.

Our fears of the technological hubris of flight, of robots that masquerade as living things, of the asymmetries of power that remote sensing produces: these are all questions that humanity has grappled with for as long as we have been aware of being human. In a way, I find this comforting. It reminds me that the societal upheaval that new technologies cause us today isn't totally novel, that history is not exactly repeating itself, but rhyming.