The Flying Lawnmower that Killed a Man

In 1979, a flying lawnmower killed someone at a football game - and society responded with a shrug.

Ever since the start of the consumer drone boom in the early 2010s, serious people have been seriously worried about the prospect of drones crashing into the bodies of the innocent. The FAA’s drone regulations include wording that directly addresses the danger of drones coming down on people’s heads, including specific rules against the waiver-less flight of drones over people and motorways.

If we take all this modern-day public concern over drone crashes into account, then it’s shocking to read about a 1979 incident where a flying remote-controlled lawnmower killed a man and seriously wounded another. During a halftime show at a New York Jets game with thousands of people in attendance. Even more shocking: the incident resulted in relatively little news coverage, and no major changes to regulations around remote control aircraft.

Allow me to set the scene.

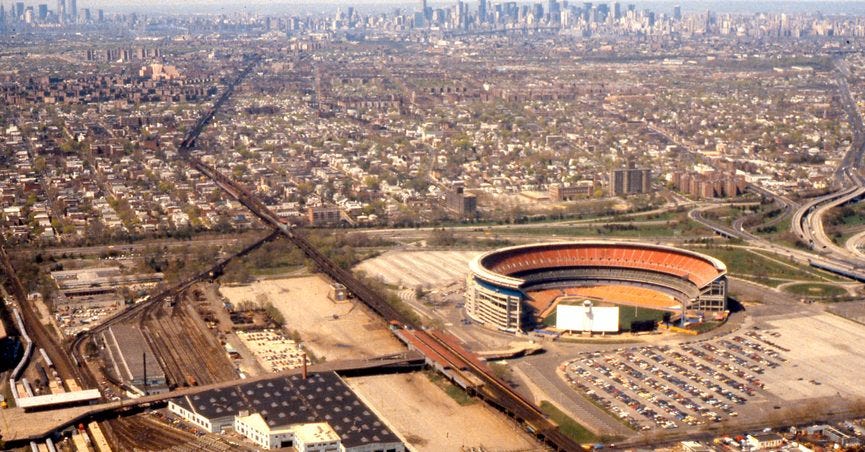

It’s December 9th, 1979, and over 45,000 football fans are sat within Shea Stadium, the now-defunct Queens edifice, not fair from the former World’s Fair Grounds. The New York Jets are playing the New England Patriots, and at this point in the game, are leading the Pats by a considerable margin.

The Electronic Eagles, a model air-show organization, are providing halftime entertainment. Founded in the summer of 1976, the organization had performed their approximately 15-minute-long shows in front of many thousands of people at many sports stadiums. But not for much longer.

Unknown to most, the Eagles were planning to pack it up soon after this show, as they’d never been able to make much money at the endeavor: for this event, they’d be taking home $800, a nice but not princely sum of $3,022 in 2021 dollars.

On the field, the Eagles begin to set up their equipment. There are plenty of regular gas-powered model airplanes, which the pilots guide through impressive trick routines. There are also two flying objects of a far stranger, more whimsical nature. One is a flying model of Snoopy’s dog house, which the Electronic Eagles would use to simulate air battles with the Red Baron.

The other is a gas-powered red lawnmower with propeller blades on its under-carriage and ailerons on the back that allow it to be controlled in the air, built from magazine plans by Brooklyn auto-collision repairman and part-time model air-show pilot Phillip Cushman.

The pilots launch into the sky, and things quickly start to go wrong. Early into the show, the flying Snoopy dog-house plummets to the ground. One of the pilots has trouble starting another plane, and the crowd begins to boo. The flustered Eagles, eager to recover from the embarrassment, bring out Cushman and his lawnmower, a usually guaranteed crowd-pleaser.

After a few stuttering attempts to start it, Cushman ushers the ungainly beast into the air, and over the heads of the spectators, launching into his own unlikely aerial lawnmower-trick routine.

In the stands are 20-year old John Bowen of Nashua, NH, apparently on his first trip to New York City with his younger brother. They are sitting close to 25-year-old Kevin Rourke of Lynn, Massachusetts. While we don’t know what the two young men made of the relative safety of a flying lawnmower swooping over their heads, the New York Times quoted Ray Warner of Montclair, New Jersey, on the matter:

“They were sending those things right over the crowd. I had an aisle seat near an exit and I had it in my mind that if it came near me, I would run. It seemed so stupid, so sick, to send this thing over these people.”

Writer and blogger Andy Harris was also there back in 1979, and so was his father. While Andy had gone to get refreshments during the incident, his father saw it all. I’ll re-quote Andy’s dad from his excellent 2019 blog post here:

“"The lawnmower plane was flying clockwise around the playing field at about the height of the top of the grandstand, with an occasional swoop downward and over the seating area. I was standing, following the show with the binoculars.

After a swoop or two at the seating area across the field the plane swooped in and failed to swoop out again, as was expected. Instead, it crashed into several spectators, who went down. The crowd started to chant "Sue! Sue! Sue! It stopped when the injured party (or parties) didn't get up, when the crowd realized that the injury was more serious than originally thought.

I don't think anyone anticipated a fatality."

Another eyewitness on the Gang Green football forums, who goes by the handle of Innocenti, had this to say about the incident in a 2014 post:

“If you youtube flying lawnmower, you'd probably see a very light looking, plastic replica of a push mower flying around. At the game, the lawnmower looked genuine. Back where the endzone/players entrance/home plate was, the lawnmower started towards the outfield. About halfway down the field, it went airborne. It flew into the outfield, then into the parking lot, around one of the outfield light posts and then back. When it got to the first base side, the controller decided to do some stunt flying over those at the lower levels. It twisted and perhaps corkscrewed. Not to long into the stunts, the lawnmower lost power and fell from the sky.

Its fall of about 20-30 feet was broken by one (and possibly more) football fans. I think it was only one fan though. An ambulance was driven onto the field from the players entrance. The victim was carted from the lower level, onto the field, and into the ambulance. Then the ambulance left. Halftime was over. I do not recall ever hearing the fate of the victim ever being announced at the game. I didn't find out until well after the game that he had passed.”

Yet another eyewitness wrote to the Washington Times in June 2017, applauding a Major League Baseball decision to ban drones inside of ballparks. He recalled that John Bowen had been reduced to a “horrible, bloody mess,” who he’d watched being carried into an ambulance. He also recalled that the lawnmower “had a particularly difficult time” of getting off the ground.

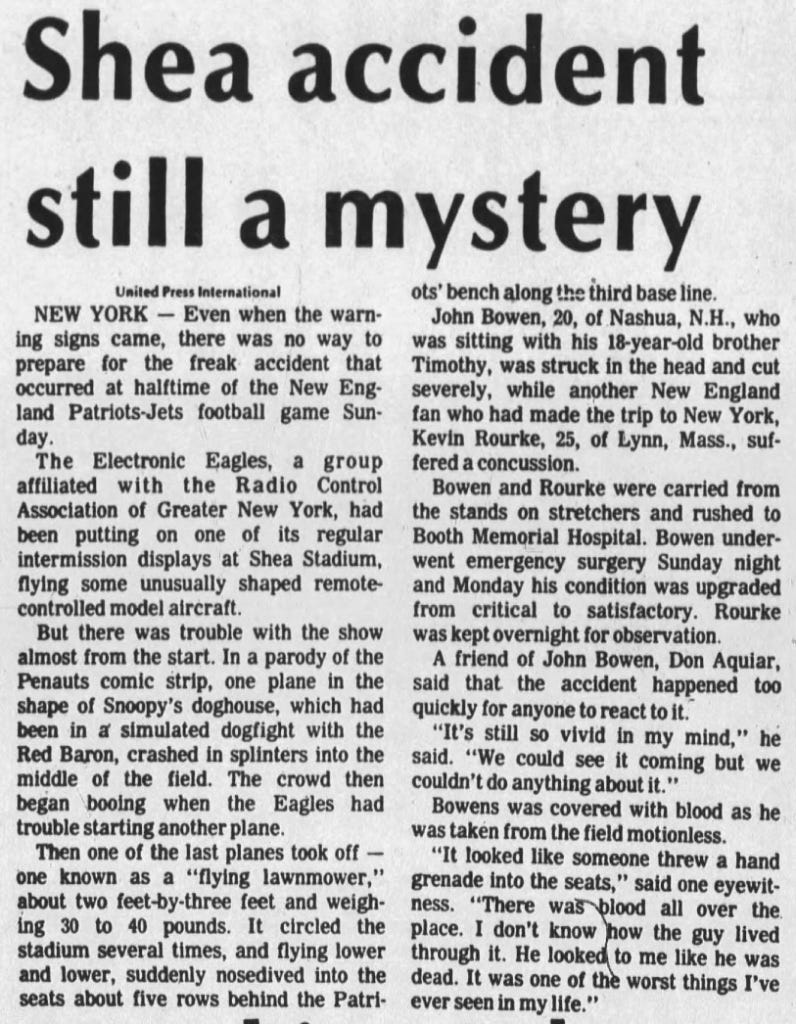

These accounts all align nicely with newspaper accounts of the event, written at the time. Per a spectator quoted in a New York Times article, Bowen looked like he had been “attacked by an ax,” while Rourke suffered a nasty concussion. A United Press International piece on the subject quotes another eyewitness, who vividly claimed that it “looked like someone threw a hand grenade into the seats.”

And that was that.

After a short delay, the Jets and Patriots retake the field – attack by lawnmower, presumably, not being considered a valid reason to cut short a football match. The Jets end up winning, 27 to 26. Rourke makes a full recovery. Bowen dies on December 15th, after undergoing surgery. The seemingly innocuous model aviation hobby had claimed a very public victim.

But how? How could a death both this public and this egregiously stupid happen? Who thought it would be a good idea to allow enthusiastic hobbyists to propel home-built flying lawnmowers right over the delicate and unprotected bodies of football fans?

In the 1970s, the answer is: “a lot of people.”

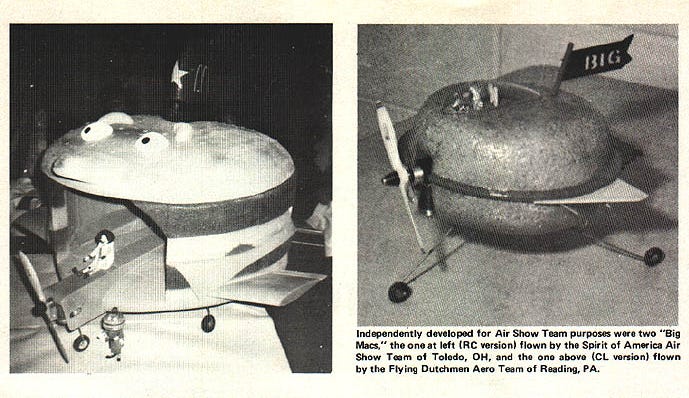

The notion of a flying lawnmower – which is, if you think about, a physical manifestation of a dad joke - dates back to at least the 1970s, and may go back even further. One famous model was designed by RC specialist Ted Teisler, and was advertised as the “Yard Bird.” Model aviation magazines regularly featured advertisements for them. Builders could send away for plans. Other bizarre flying machines were also rather in vogue in the 1970s, like the aerial cheeseburgers featured in a July 1978 issue of Model Aviation.

Today, flying lawnmowers still ply the skies of air shows, seemingly free of any deadly reputation. Until a few years ago, you could order a flying lawnmower kit from a number of companies, and the plans are still widely available for free online. Model airplane forums regularly see users who have decided to try making one. Supposedly, in the right hands, they fly rather nicely indeed.

YouTube features a wide assortment of flying lawnmower videos, usually shot at air shows, usually with whimsical narration provided by an older guy in a large hat and tube socks (which is the national uniform of middle-aged model airplane enthusiasts). There was even a massively popular, very good, Vine with a Mariah Carey soundtrack.

In the 1970s, model airplane enthusiasts were also a regular sight at US halftime shows, impressing audiences with displays of soaring and largely home-built aircraft of various makes and models. Flipping through old remote control magazines confirms this, such as this clipping from a January 1979 issue of Flying Models magazine describing a model airplane halftime show at a Seahawks game.

The Electronic Eagles were a sub-group of the Radio Control Association of New York, a respectable model airplane hobby group who are affiliated (like other hobby groups of their ilk) with the mighty Academy of Model Aeronautics, or the AMA. The AMA dates back to 1936 and was, by 1979, a venerable institution amongst US model-airplane builders, as well as the publisher of the popular monthly Model Aviation Magazine. Back then and today, the AMA offered pilots access to flying fields and model aviation events, as well as liability insurance for RC model pilots.

Prior to that day in December 1979, the AMA appeared to be a fan of the Electronic Eagles specifically, and the practice of model aviation air shows more generally. From the AMA’s perspective, these air shows exposed general audiences to the fun of model-airplane building. They hoped that these demo air shows would bring fresh blood into the hobby, inspiring new generations to take up balsa wood, glue, and little fiddly motors.

By December 1977, the AMA had twelve teams participating in its National Air Show Team program (which the Electronic Eagles were not part of), and the organization hoped to encourage the formation of more teams across the country. Many, if not most, of these shows were held in outdoor fields – far safer environments for RC flight than a crowded sports stadium.

But of course, not all.

In a December 1977 issue of Model Aviation Magazine, then-AMA President Johnny Clemens described an Electronic Eagles half time show at a match between the Pittsburgh Steelers and the Oakland Raiders with praise:

"I just now looked up from my typewriter in time to see SNOOPY and the RED BARON putting on a halftime show at the Pittsburgh Steelers-Oakland Raiders football game. And this RC demonstration was on national TV!" Model plane demonstrations are being used as rest-period or halftime entertainment at baseball, football, and soccer games on a rather regular basis anymore. And they are always enthusiastically received."

Rather presciently, Clemens also wrote this:

"BUT A BIT OF WARNING! Make SURE that public SAFETY is your first consideration if you are planning such a show. To "mess-up" at a public gathering like that would do far more damage than any good that might be gained."

In that same December 1977 issue, John Byrne, the vice president of the AMA’s New York-based branch replied with amusing snark to an accusation made by another, rival AMA vice President, who claimed that Byrne had “touted” his branch’s show team activities in a “less than wholesome way.”

Byrne first whips out some figures, claiming that the Electronic Eagles of the Radio Control Association of Greater New York performed before 36,800 spectators on June 4, 1977 (and that he’s got receipts to prove it). He then writes:

"The significant thing about this particular PR shot is that we got our message to a large segment of the non-modeling, uninformed public, rather than folks who are either modelers themselves, or at least already know what we do. So much for "touting!!”

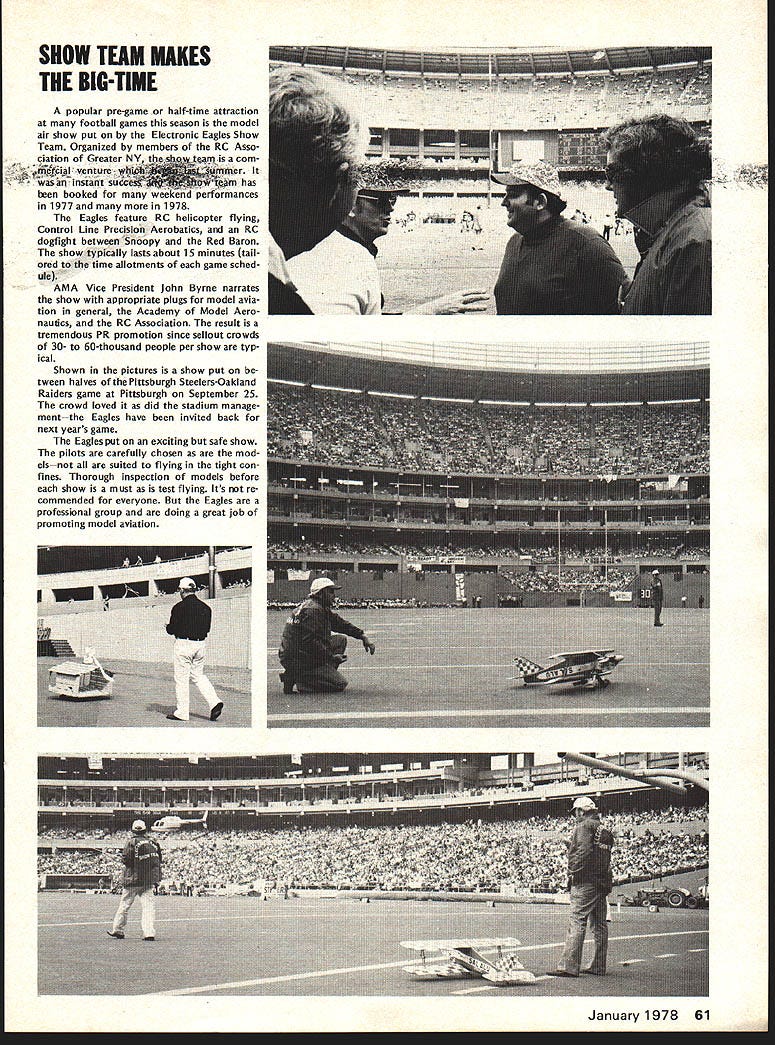

A January 1978 issue of Model Aviation included a full page feature on the Electronic Eagles with pictures from the September 1977 Pittsburgh halftime show, including the ill-fated flying Snoopy doghouse. The aforementioned John Byrne, the article notes, provided both narration of the show and “appropriate plugs” for the model aviation hobby.

Again, the article makes exculpatory reference to the rather obvious question of safe flight in the crowded confines of a football stadium: “The pilots are carefully chosen as are the models – not all are suited to flying in the tight confines. Thorough inspection of models before each show is a must as is test flying. It’s not recommended for everyone. But the Eagles are a professional group and are doing a great job of promoting model aviation.”

By February 1978, it was clear that some people in the model airplane community felt - quite correctly, as it turned out - that flying large model aircraft at crowded sports games was unsafe. In that month’s issue, Model Aviation felt moved enough by these criticisms to issue a retort. “Although some risk is involved, these events present an outstanding opportunity to “sell” aeromodeling,” the club noted, adding that the Electronic Eagles “have been a credit to all modelers.”

Imagine, if you will, what would happen if a drone killed a guy at a football game today. Every tech writer in the country, including myself, would be publishing a sea of editorials on the broader implications.

In that light, the aftermath of the Shea stadium incident was startlingly muted. It was the pre-social-media era, and there appear to be no surviving videos or photographs of the actual air show, or the bloody aftermath. For whatever reason, people largely did not view Bowen’s death as a dark commentary on the dangers of modern technology, as today’s drone mishaps tend to be viewed. Unfathomably upsetting as it had been to witness, it was largely viewed as just a Thing That Happened – a freak accident, not an indication of a grim societal shift or a broader threat.

In a New York Times piece a few days after the event, but prior to Bowen’s death, Cushman claimed he “just lost control,” and added (probably wisely) that his “lawyer said I shouldn’t make any statement.”

Electronic Eagles spokesman Richard Brooks, speaking to UPI, said: “"We've done 30-some odd shows all over the country and nothing like this has ever happened. To tell you the truth, we're not exactly sure what went wrong with the plane."

Jets show organizer Bob Cleveland – who also worked as a public school music teacher – expressed shock over the accident. “I certainly won’t use them again, that’s for sure,” he said, in what may be one of history’s great understatements.

Cushman, far as I can tell, vanished swiftly into obscurity, and so did the Electronic Eagles. Nothing ever seems to have been published on what, exactly, went wrong with the flying lawnmower, or why Cushman had lost control of it.

In July of 1980, New York City Council member Antonio Olivieri proposed a new bill which would limit RC aircraft operation, including, presumably, in stadiums. Olivieri also took the time to write a letter to the AMA’s executive director, in which he said that he’d let the bill drop if the AMA changed its safety code to prohibit flight in stadiums.

The AMA took the hint.

The organization very swiftly changed its tune on the advisability of stadium air shows, aware as it was of how their former PR-play had, nightmarishly, turned into the exact opposite.

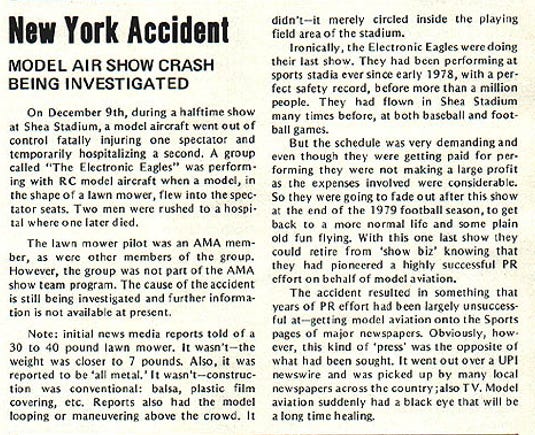

A AMA news article from April 1980 on the incident noted pilot Philip Cushman and the other Eagles members were all members of the AMA, although they were not part of the official show team program. The article also clarified that initial media reports about the lawnmower weighing 30 or 40 pounds were wrong: “the weight was closer to 7 pounds,” and the AMA claimed that it was constructed from “balsa, plastic, film covering, etc.”

The AMA’s article contradicted other reports of the incident, stating that the model didn’t loop or manoeuvre above the crowd, but instead “merely circled inside the playing field area of the stadium.” Ruefully, writes the AMA, "The accident resulted in something that years of PR effort had been largely unsuccessful at - getting model aviation on the Sports pages of major newspapers…. Model aviation suddenly had a black eye that will be a long time healing."

Other members of the AMA took the stance that the incident was a freak happening. Wrote Chuck Foreman, the District IV vice-president of the AMA: "Don’t get me wrong - I am very sorry it happened, but let's not make any rash decisions before we know the facts. Let's look at what happened and learn from it."

By January 1980, the AMA announced it was working on an addition to its safety code requiring better separation between spectators and aircraft in air shows: it also appears to have stopped issuing insurance coverage to stadium performers. By 1981, the AMA’s Executive Council had effectively banned remote control air-show flights in stadiums with spectators. The halftime show era of model aviation had come to an end.

John Bowen’s father filed a $10 million damage suit in Brooklyn’s Federal District Court in November 1981, naming the New York Jets, the Radio Control Association of New York, and Philip Cushman as defendants. But far as either I or Andy Harris could determine, there’s no official word on what came of the lawsuit.

There is, however, a potential clue in the December 1985 issue of Model Aviation: then AMA Executive Director John Worth noted that, in the Shea Stadium case, “AMA’s insurance paid the bulk of the settlement.” You may also notice that this contradicts the February 1978 issue of Model Aviation, where the club states that the Electronic Eagles “operate independently of the AMA Show Team program, using their own liability protection.” (Perhaps they signed up afterwards).

Perhaps most shockingly from the perspective of a 2021 drone enthusiast, the FAA had relatively little involvement in the matter.

Speaking to the New York Times, a regional FAA official said “he foresaw no restrictions because of the “extreme” difficulty in enforcing such rules.”

I don't think the F.A.A. on a broad program could control it,” he said. “Model planes are flown all over the country; who knows how many are doing it? Model airplane flying could be done by a youngster of any age or an oldster of any age. Regulations would be extremely difficult to control or enforce.”

The FAA eventually did do something. In June 1981, the FAA issued an update to the pre-existing 1972 Model Aircraft Operating Standards (which had been published in the pages of the AMA’s magazine). The non-binding Advisory Circular 91-57 would, the FAA hoped, encourage “voluntary compliance with safety standards for model aircraft operators.”

The main difference from the old version: the 1981 version added specific language instructing model aircraft users to operate at “sufficient distance from populated areas” and that they should not operate model aircraft in the presence of spectators “until the aircraft is successfully flight-tested and proven airworthy.” As they say, every regulation is written in blood.

While the AMA feared the hobby would suffer a “black eye that would take a long time healing,” my review of the historical record shows that their fears were overblown. Instead, the model aviation hobby continued to roll along, largely unregulated, for decades. And largely, it did so very safely, in no small part due to the AMA’s willingness to swiftly change its practices in response the 1979 incident.

This happy state of affairs, from the model airplane people’s perspective, would continue until all hell broke loose with the rise of inexpensive and easy-to-fly consumer drones in the early 2010s, coupled with intense new public debate over the advisability of flying unmanned aircraft over people’s heads.

What can we learn from the flying lawnmower that killed a man?

First, we can learn from the AMA’s fairly swift response to the incident, and its willingness to adapt its behavior. Many organizations have done far worse, and have proven more resistant to change. The AMA did what it should have done.

The Shea Stadium tragedy is also an interesting look at how much the timing of an event can impact how much people care about it. In 1979, remote controlled airplanes were largely viewed as the products of an innocuous hobby for well-meaning nerds. While military drones certainly existed at that point in history, people simply didn’t seem to think of them as particularly related to the little airplanes their neighbor down the street put together in his free time.

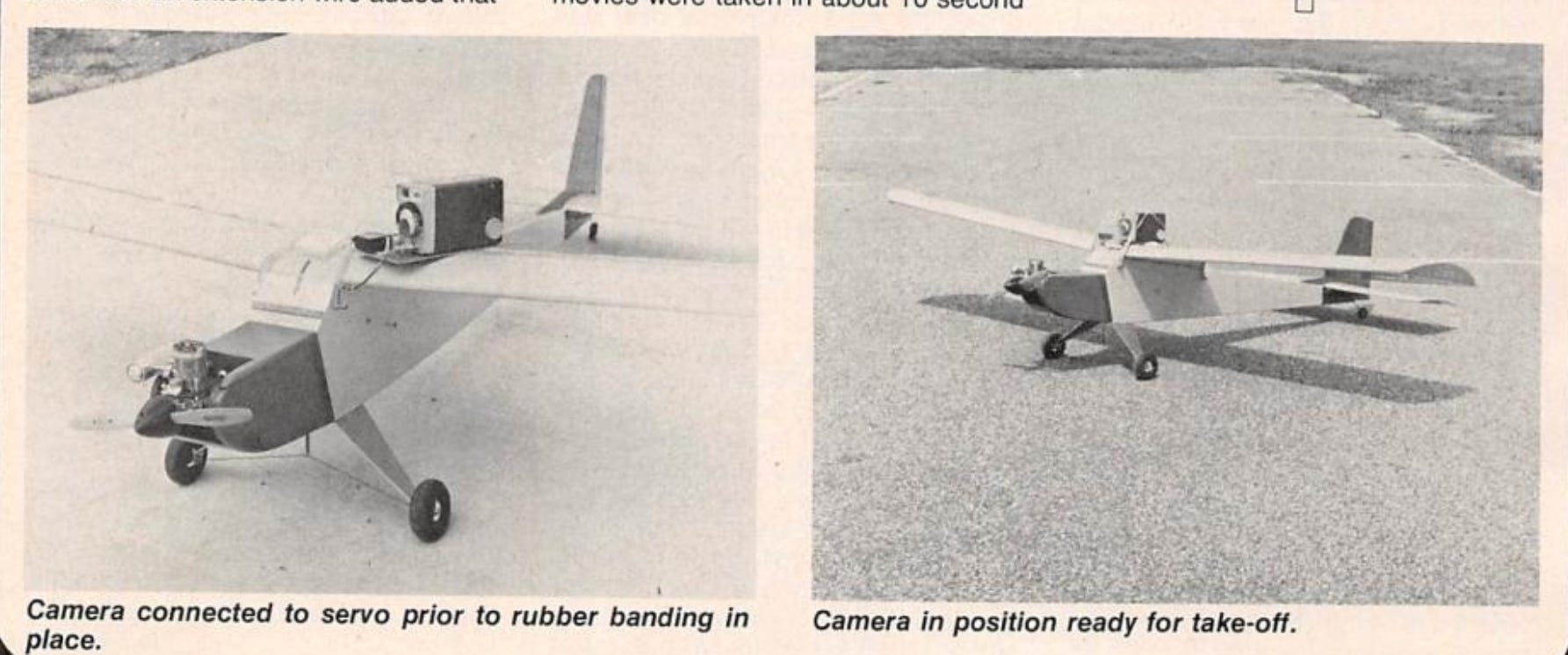

Nor did people seem to connect remote controlled hobby airplanes with cameras, or with surveillance. Your average person largely weren’t aware that hobbyists were already building model airplanes that could carry cameras (and using them to shoot pictures of their neighborhoods) by the 1960s and 1970s. Even if they were aware of such a thing, it’s not clear how they would have interpreted it. A single, nasty, death wsn’’t enough to make society change its view of the relative scariness of remote controlled aircraft.

It needed more.

Arguably, the War on Terror and the widely publicized rise of armed Predator drones provided the first piece of the puzzle, making the average person available for the first time of remotely-piloted aircraft’s potential beyond entertaining air shows.

The huge popularity and dirt-cheap price of the consumer drones of the 2010s - drones that, I should note, originated from the civilian RC hobby, and not from military sources - delivered the second part. Add the rise of the information age and ever-present fear of terrorism and mass surveillance into the mix, and, well, there we are. Remote controlled aircraft, even hobby remote controlled aircraft, are now publicly associated with danger, menace, and surveillance, in a way that they simply weren’t back in 1979.

Today, the safety record of both more traditional remote controlled airplanes and helicopters, and the computerized aircraft we now typically think of as “drones,” remains quite impressive. As of this writing, there’s no documented case of an aircraft that most people would consider a modern-day small civilian drone killing anybody by running into them, although there have been a number of injuries (mostly involving propellers and fingers).

Deaths involving more traditional, non-computerized model aircraft also remain extremely rare, albeit not unheard of, like a grisly incident in 2013 where a young Brooklyn model helicopter pilot was killed after his large model helicopter sliced off the top of his head.

Still, the potential for mishap and danger remains. In the US, we collect very little data on drone crashes and the relative safety of different models: we also have no idea how many drones flown for public safety purposes over often crowded areas, like police drones, crash or malfunction. (I wrote about this recently for Brookings). Massive stadium and public event shows involving drones are also very much in vogue, popping up at the Super Bowl, the Olympics, and other major events. And they’re not without risk.

In May 2020, seventeen drones crashed in Chengdu after an employee from a competing drone company allegedly jammed the aircraft in an act of revenge. In early October 2021, a huge drone light show in China suffered a major malfunction: dozens plummeted from the sky over the crowd of 5000 people, many of them children. We should take the Shea stadium incident as a warning that a tragedy like that can happen again - and public reaction to it will likely be a lot more ferocious than what happened in the aftermath of 1979.