The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Preface

To build new technology, we must imagine it first. Every technological marvel that humanity has ever come up with came into being by this process of imagination, of both individual and collective musing about things we’d like to do, and the tools we might be able to build to help us do them.

Crucially, this is an additive process. Sir Isaac Newton famously wrote "if I have seen further [than others], it is by standing on the shoulders of giants” in 1675. Not that he was the first person to think of this: he was repeating an aphorism that had been kicking around the European psyche since at least 1123.

Who, exactly, did Newton mean by “giants”? I suspect most people assume he was specifically referring to scientists and natural philosophers - the usual towering, engineering-minded figures that most everyone is inevitably educated about at some point in school. However, this traditional take on the history of science and technology, inflicted on the world’s bored 8th graders, leaves an enormous amount out.

When we think of the aforementioned giants, we should also be giving credit to history’s writers, fabulists, theologians, story-tellers, and shamans (among others), whose essential imaginative and creative contributions initiated long processes that would eventually culminate in everything from moving pictures to washing machines to, well, drones. Taken together, you can imagine Newton - and everyone else who came after him, and you, and me - wobbling awkwardly around at the swaying top of an incredibly structurally perilous tower of raw human inspiration.

Humanity needed a lot of giants, and a lot of shoulders, and a lot of weird ideas to eventually end up at today, where we’ve taught sand to think and little robots to fly. If we want to figure out where drones came from, this means that we need to look at lot further back than the early 20th century (which is where histories of drones usually start, somewhere in the vicinity of World War One's flying targets). We need to take into account not just the history of engineering, but also of drone-like ideas. That's how both human beings and human creations seem to work, in a cycle that stretches back to the beginning of recorded history (and almost certainly further back) : one creative idea leads to another, and so on to another, forming an interlocking pattern of cognitive connections that can stretch across generations, centuries, and millennia.

Sometimes, at times that are fiendishly difficult to predict and to anticipate, all that feverish human activity - both creative and pragmatic - produces something tangible. Suddenly, we’ve figured out how to actually build an object that, for a terrifically long time, only existed as a story. As a metaphor. As a dream.

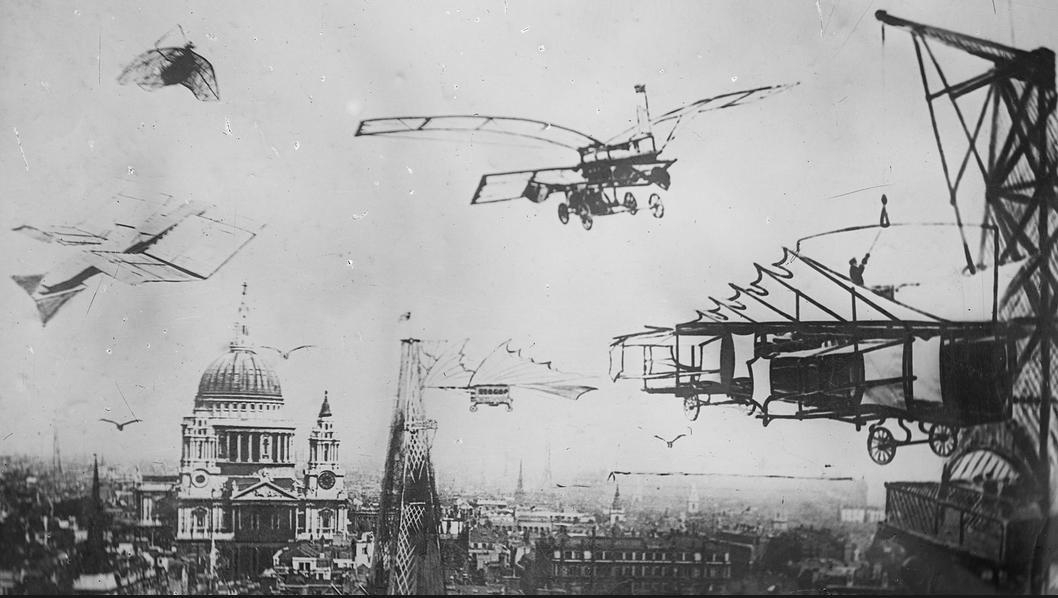

yeah it didn't quite go down like that

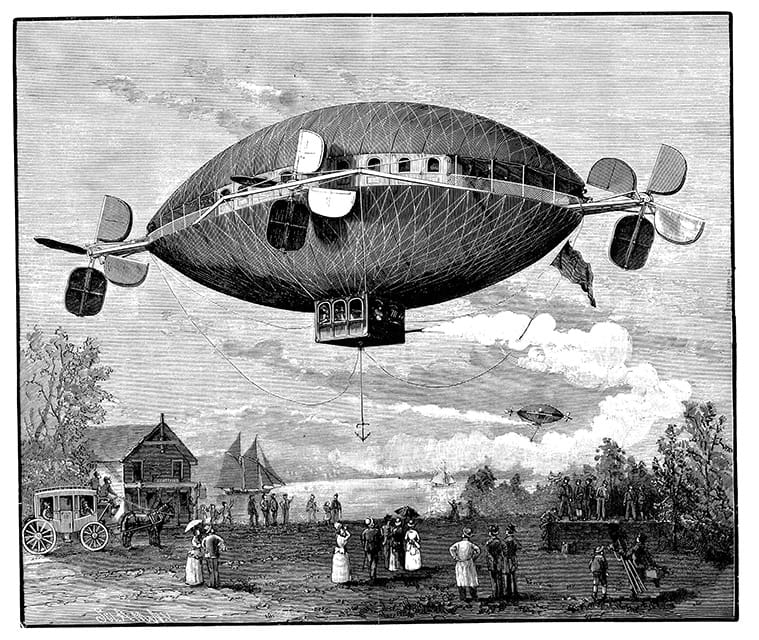

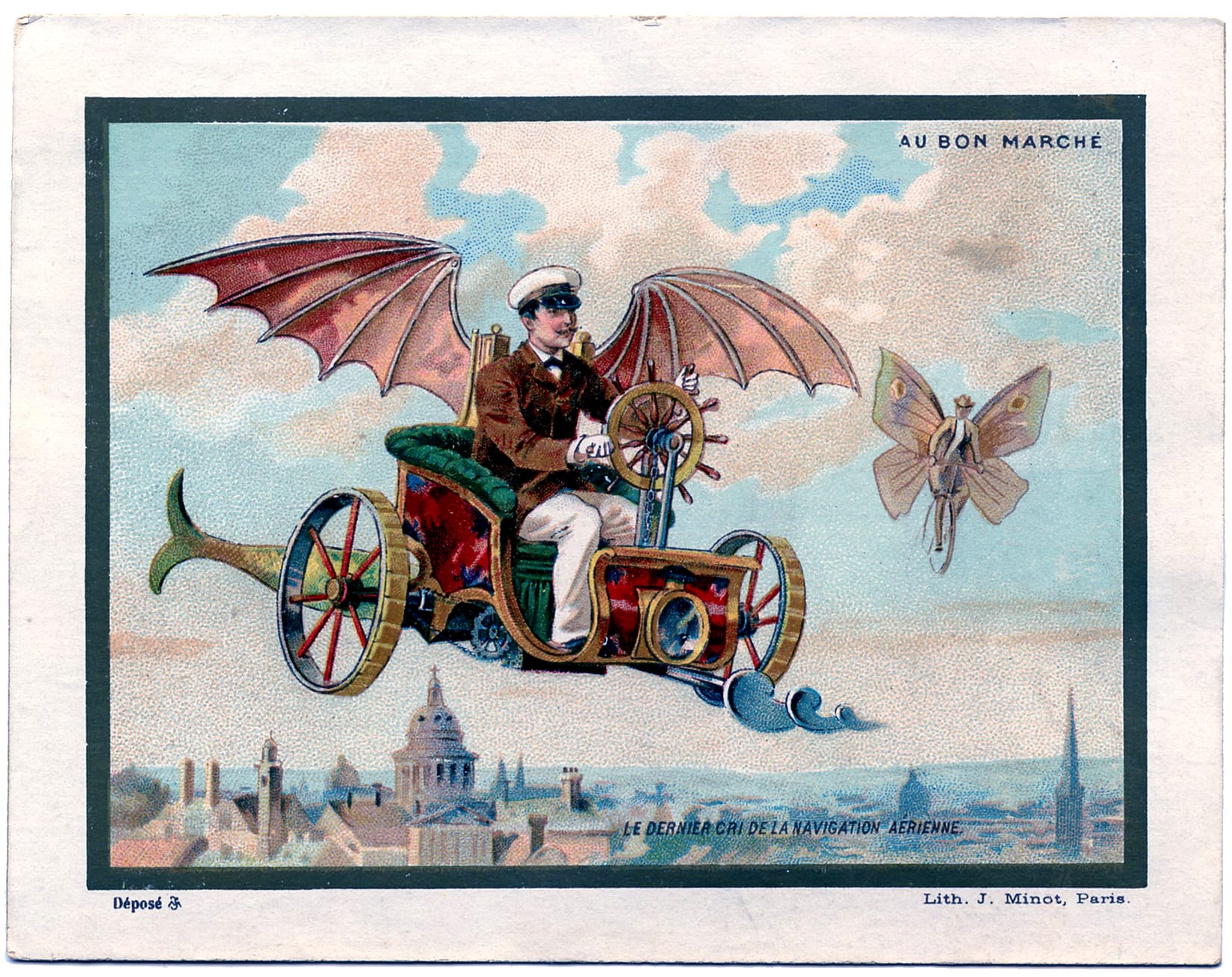

For the last 200 years, our species has collectively been doing a lot of this plucking-ideas-from-the-collective-consciousness-and-giving-them-form sort of thing, to an extent that arguably outpaces any other point in human history. We deal daily with machines that our not-too-distant ancestors would regard as science fiction - although those machines have, inevitably, taken rather different forms than what people like Jules Verne would have assumed. We still don't have flying cars, and people aren't crossing the Atlantic in zeppelins while wearing top-hats, but we do have effective MRNA vaccines, microwaves, and tiny pocket-computers that give us anxiety.

I don’t know if giving a single Dorito to a wan and bookish Victorian child would actually kill her, as the meme goes, but she’d probably be pretty impressed by how many concepts she’d only encountered in works of fiction have now become mundane parts of our daily lives, including flying vehicles, magical mirrors capable of viewing happenings far away in real time, and machines capable of moving around on their own.

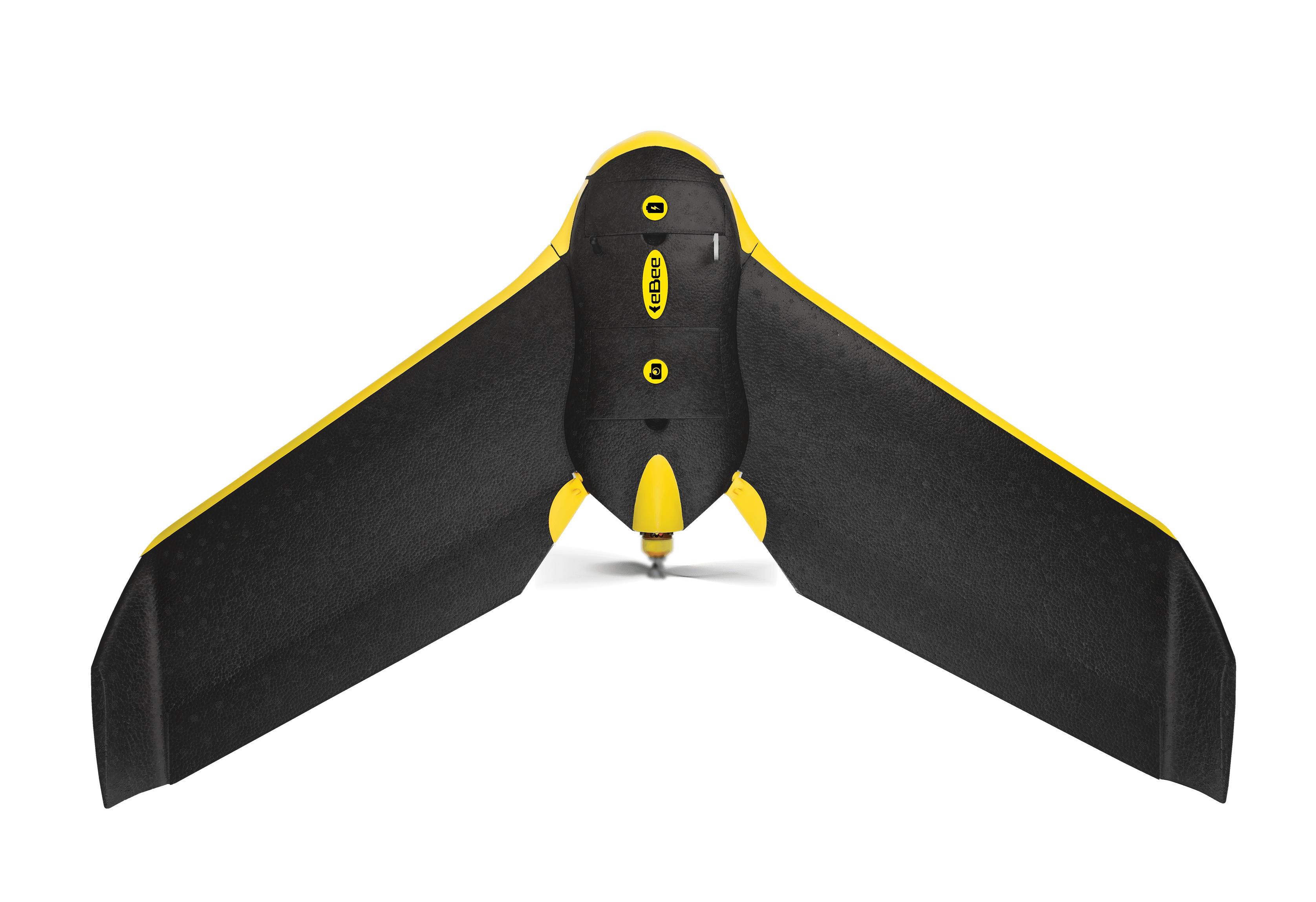

And as it happens, all three of those formerly fantastical, wacky ideas have been combined, in the last 15 years or so, into a single familiar object: the modern consumer drone.

the sensefly ebee, the DJI Mavic, and the Keyence Gyrosaucer, one of the first mass market quadcopters

I work with civilian drone technology for a living, and I find them deeply fascinating (which I’ve written about before). This series of posts will be about a key element of that fascination for me: how drones represent the culmination of a lot of creative and mythological ideas that harken all the way back to the deep origins of humanity.

Even more specifically, this series will be about the three dreams that humanity had to have before we could combine them into the single, tangible thing that is a modern drone.

The first dream was of being able to see things taking place far away from our physical bodies. Thousands of years before the invention of FaceTime, people were pondering what it might be like to be able to keep tabs on things that were happening far, far away from the location of their physical bodies. Ancient shamanistic traditions often involved techniques for disconnecting one's soul from one's body - sometimes into the vessel of an animal, sometimes with free and airy independence - and then deploying that consciousness to places improbably far away. Mythology and folklore is full of stories about magical mirrors, surveillance spectacles, and other tools for viewing (and communicating with) places and people from a great distance.

The second dream was of being able to fly in the air, like a bird. Everyone knows about the watery fate of Daedalus, but mythology is full of other accounts of people who flung themselves off high buildings in pursuit of flight, including the legendary English king Bladud, the kite-flying Chinese hero Yuan Huangtuo, and a succession of monks, philosophers, and other assorted eccentrics up until the modern area. Other luminaries wisely declined to put themselves at risk and tinkered with building flying machines of their own (or so the old sources claim), from the philosopher Archytas of Tarentum and his steam-powered bird, to the Chinese philosopher Kungshu Phan, who is said to have created a bamboo bird that stayed aloft for three days without needing to return to the earth.

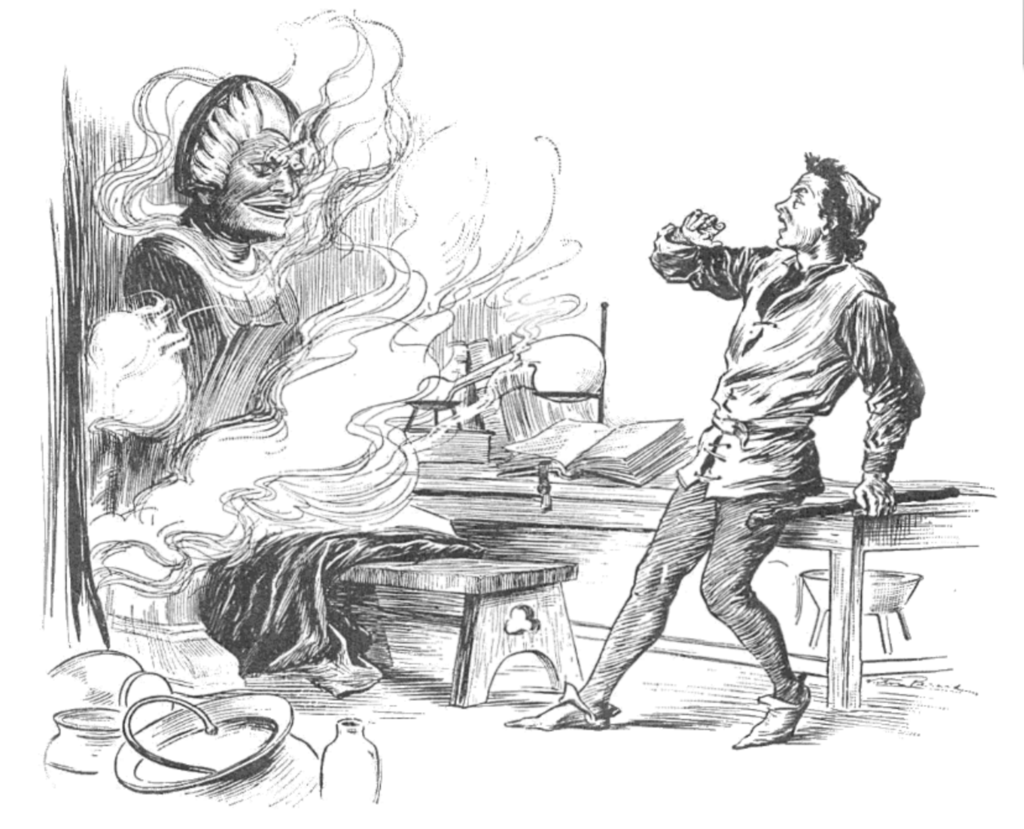

The third dream was of being able to create objects that could move and think on their own. Ancient Greek mythology is filled with stories of early automata, from the self-piloting ships of the Phaeacian people encountered by Odysseus, to the distinctly robot-like golden cauldrons created by the god Hephaestus, which could deliver ambrosia and nectar to other deities on command - imagine a sort of celestial Uber Eats.

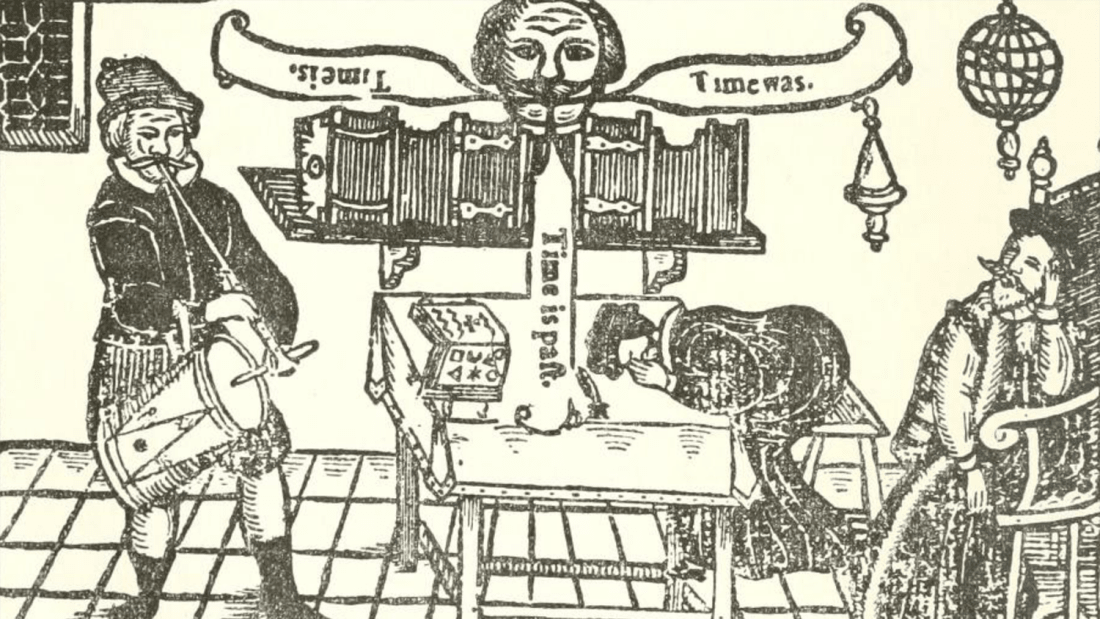

In later history, the Byzantine Emperor Theophilos was said to have a mechanical throne both wondrous and terrifying, which could grow to a great height and was flanked by mechanical golden lions and a similarly artificially animated gilded bronze tree, which was filled with singing birds. In 1532, Rabelais coined the term "automate" to denote "a machine with a self-contained principle of motion in Gargantua." Indian myths describe fearsome automated armies of artificial men, while a succession of 12th and 13th century English philosophers were claimed to be the owners of a talking mechanical head - which, according to one version of the tale, was so incredibly annoying that Thomas Aquinas himself destroyed it to shut it up so he could focus on his work.

the Brazen Head, annoying people

Each one of these dreams contains many stories and ideas, mushed together from all over the world and all over time, but revolving a certain single, technological theme. And each one is of equal importance. In the absence of any one of these dreams, humanity would never have been able to come up with such a thing as a modern camera-carrying drone. Exclude any one of them, and the whole apparatus falls apart.

And yet, humanity did, in the course of time, have all of these dreams, and humanity did figure out how to combine them all into a single, mechanized whole. And now we’re living in a world where anyone with opposable thumbs and a few hundred bucks to spend can buy their very own aerial robot equipped with the capacity to view the world from above. It’s really weird, if you think about it. Which I have, probably too much, and which I’m going to try to convince you to do too.

In this series of posts, then, I’m going to explore each of these dreams, and look at history’s long list of people who had them - each one (usually) unknowingly scrambling on top of the shoulders of another, each one contributing their own small stick to an eventual bonfire. Though I absolutely would not advise starting fires on the top of a Leaning Tower of Pisa of wobbly human bodies.

Yes, this series is about drones. But it’s also not just about drones. I hope to make this interesting even if you couldn’t care less about drones, or actively want to shoot down the one your stupid neighbor keeps flying over your yard.

I focus on them here because (1) they’re objects I happen to know a lot about, and (2) they combine hardware, software, and data-collection in ways that I think are particularly evocative, fascinating, and (obviously) threatening.

While I’m obviously personally invested into drones, I also think they’re a case study that’s representative of bigger truths. They represent a superb example of how the novel technologies that alternately fascinate and torment us today are not so novel after all. Sanctified guys in Silicon Valley garages didn’t come up with the modern consumer technology revolution out of nowhere (though those guys often would like us to believe they did). They stood on the shoulders of giants: they built objects that might appear utterly novel, but were in fact rooted in concepts and ambitions and fears that stretch far back in human history and in culture.

On one hand, I find learning about this connection between humanity’s oldest ideas and our newest inventions to be comforting. It reminds me that as horror-filled our technological future often seems to be - and the horrors certainly are coming at us quickly nowadays - we are not being confronted with things that are totally novel, or that we lack the capacity to understand.

Because, as it turns out, our ancestors have been grappling with conceptual, technological problems that aren’t so far off from the ones we face today. We’ve been both creating and freaking out over technological dystopias for a lot longer than you’d think.

On the other hand, I also find it a little bit existentially terrifying to contemplate how the seeds for the modern technological dread so many of us face today were planted not a few decades ago, or even a few centuries ago, but thousands of years ago - eons before we could have any say in the matter. And here we all are, having to deal with the eventual ramifications of oddball stories, many of which can plausibly be traced back to the dawn of human history itself.

Like it or not, we exist at a point in history in which a lot of these ancient dreams are converging into tangible, tactile form. Or, to put it in the words of an ancient Jewish tradition, we’ve awakened a whole mess of golems from potential-filled clay, and now it’s up to us to figure out what to do about them.

I hope that writing this series helps me answer that question. Maybe it will help you too.

Here are the entries in this series so far:

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Preface

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: A Drone of The Mind

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Forgotten Technologies, Towers, and Roman Shitposting

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Death Rays, Brass Horses, and Dragon-Surprising Mirrors

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Pondering Orbs, Black Mirrors, and World-Viewing Cups

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Tower-Jumpers and Hungry Eagles