The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: The Fear and Fantasy of Flying

There is something deeply rooted in our psyche that is both appalled and fascinated by the prospect of a human being flying like a bird, by this act that is both deeply unnatural and has also become, over the course of about 120 years, totally pedestrian for us jaded residents of the modern world.

Before the Wright Brothers first shuddered into the air in 1903, and before two adventurous Frenchmen made the first crewed ascent in a hot air balloon in Paris in 1783, humanity spent thousands of years in a state of both angst and aspiration about the dual promise and peril of lighter-than-air flight. Mythology, philosophy, and folk-tales all frequently speculate about what might happen if human beings could view the earth from far above, or could soar through the air to rapidly arrive at distant destinations.

In some cultures, certain legendary warriors are afforded the power to fly, like the Ugandan hero and war-god Kibaga (or Kibuka), who, per an account from the famous explorer Henry Morton Stanley, allegedly used his aerial powers both to spy on his foes and to shower rocks on them from immense heights. Per some accounts, Kibaga did these deeds while concealed by a magical, invisible cloak, in what seems like a very early stab at the idea of stealth aerial warfare:

In ancient China, certain particularly adept Taoist scholars and immortal "wizards" (xian/hsien) were claimed to have had the ability to fly, an idea that likely can be traced back to ancient shamanistic traditions about "soul flight" (which I discussed earlier in this series). Per the historian Joseph Needham, the association between Taoism and flight was so strong that Taoist priests are still sometimes referred to as "feathered guests" even in our own time.

Well before Sally Field ascended into the sky as a flying nun in 1967, the iconic Taoist scholar Zhuangzi was supposedly writing in the Warring States era (403-221 BCE) about the Taoist master Liezi, who he claimed was capable of flying in the air for as much as fifteen days at a time, freely riding upon the wind:

Similar aerial concepts emerge in the 2nd A.D. Chinese collection of poetry known as the Chu Ci, specifically in a work titled "Sorrow for Troth Betrayed" - in which the narrator, quite relatably, grows so disenchanted with the ever-worsening world that he decides to take to the skies:

Some cultures take a more practical approach to tapping into the spiritual powers of flight, such as certain indigenous groups in Mesoamerica who still perform an ancient aerial ritualistic dance known as the "Danza de los Voladores," in which people tethered by their feet, dressed in costumes with feathered motifs, rotate with surprising tranquility around a 30-meter tall pole. Another person sits at the very top of the pole while the others "fly" around it, playing a lively tune on a flute.

Most experts think that the dance originated as a fertility ritual at certain celebratory events, which morphed in the post-colonization era to additionally honor God and the Saints. Others think that this "bird man" ritual is linked to efforts to call rain to prevent deadly drought, or perhaps as a means of warding off hurricanes. Certainly, the dance is linked to birds, and the feathered costumes the dancers wear likely have something to do with the close relationship between the eagle and the Mesoamerican god of the sun.

You can easily see a portion of this sky dance yourself if you visit Mexico City, where performers execute it for tourists multiple times a day in the park, right in front of the glorious Museum of Anthropology. (Please give the dancers a tip).

Earlier in this series, I described how a number of very old beliefs rooted in shamanism and other global spiritual traditions concern a type of aerial travel of the mind, various mechanisms by which spiritually-tuned in individuals can project their consciousness over vast distances.

In this section of the series, which will revolve around the importance of the human dream of flight for the development of modern drone technology, I'm concerned with historical ideas about more earthly, embodied, and nitty-gritty mechanisms for human aerial travel - like so-called "forgotten technologies" for crafting flying machines, ancient experiments with man-lifting kites, and distant experiments with uncrewed model aircraft.

While humanity has been screwing around with developing flight technologies in one form or another for a dazzingly long amount of time, we have spent just as much time worrying about what might happen if we succeeded (and certainly, many people believed that human flight would always remain impossible).

If ancient stories and myths about human flight share any consistent theme, it is most certainly that of hubris. While certain extremely spiritually powerful or clever human actors, like the Taoist master Liezi, are capable of flying without coming to a bad end, there is a consistent sense in old literature that flying should really only be reserved for gods and birds.

And indeed, human flight is one of our oldest and most deeply rooted technological anxieties, a clear antecedent to today’s debates over the relative badness or goodness of everything from social media to genetically modified organisms to AI chatbots.

In the pre-modern era, in that time before modern Silicon Valley-fueled techno-optimism devoured the world, people seemed more broadly skeptical about the dangers of technological innovation than they are today, less willing to cheerfully accept that the benefits of granting new capacities to humanity must always and inevitably outweigh the drawbacks.

Writers stretching from antiquity to the Enlightenment wondered, often quite accurately, about how we might use our new-found powers of flight not just to expand commerce and to make scientific discoveries, but also to kill each other from ever greater distances, and at ever greater volume. They wondered about how humans imbued with flight might use those capabilities to spy upon each other, to ruin each other's peace, and to sow confusion and violence.

And indeed, all these things did come to pass, a dynamic that I wrestle with regularly today as a specialist in civilian drone technology, as someone who feels invested in puzzling out how to balance the remarkable positive uses of little flying robots for aerial data collection against their undoubted usefulness for low-budget murder.

Fear of Flying

The previously-mentioned ancient Roman writer Lucian wrote an entire comic drama about the adventures of a comedy-inclined and very real philosopher named Menippus, who grows so despondent about ever being able to find knowledge from the endlessly-arguing denizens of Earth (along the lines of the earlier-mentioned 2nd A.D. Chinese poet) that he appropriates wings from an eagle and a vulture and ascends into the heavens to seek a more final sort of truth. While Menippus does not die in this pursuit, and eventually ends up both meeting a surprisingly understanding Zeus and catching a ride back home from Hermes, Zeus also makes it very clear that he is not to repeat this little stunt again.

Much later in in history, as the Renaissance and the Enlightenment made the prospect of genuine human flight seem less patently absurd, scholars continued to worry about the criminal dangers and social impact of a world where people could fly like birds.

The Italian Jesuit priest and engineer Francesco Lana de Terzi is widely viewed as one of aviation's early pioneers for his plan for a vacuum airship (more on that later) - but unusually, he also wrote eloquently about the dangers that his own invention might someday introduce into an unprepared world:

Similar concerns were expressed by the English clergyman and scientist William Derham, writing in 1720 (still well before the Montgolfier brothers and their balloons):

Similar concerns about the exotic moral depravities that human flight might introduce into the world were expressed by the French priest and naturalist Noël Antoine Pluche in his nine-volume 1754 tome "Spectacle de la nature" :

Yet another famous early warning about the dangers of flight comes from the eminently meme-able 18th century polymath poet Samuel Johnson, who wrote in his 1759 "The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia":

“If men were all virtuous,” returned the artist, “I should with great alacrity teach them to fly. But what would be the security of the good if the bad could at pleasure invade them from the sky? Against an army sailing through the clouds neither walls, mountains, nor seas could afford security. A flight of northern savages might hover in the wind and light with irresistible violence upon the capital of a fruitful reason. Even this valley, the retreat of princes, the abode of happiness, might be violated by the sudden descent of some of the naked nations that swarm on the coast of the southern sea!”

Guys With Wings Stuck on Their Arms

To writers of old, there were few morality tales quite as potent as those that concerned guys with wings stuck on their arms. Most of the time, the guy with wings stuck on his arms comes to a bad end himself. Sometimes, the guy with wings stuck on his arms makes bad times for other people.

In either iteration, the narrator tends to place a lot of emphasis on a central and indisputably accurate truth: when humans try to fly in the same way birds do, someone is going to pay for it one way or another.

Most everyone is aware of the tale of Icarus (and indeed, I brought him and his long-suffering father, Daedalus, up in an earlier entry in this series). I probably do not need to rehash it in great detail here, beyond the central idea that a clever Ancient Greek inventor who is trapped in a tower with his son makes wings for them both, they successfully fly away towards freedom, and it all goes horribly wrong when the son grows too bold, flies too close to the sun, destroys his wings, and dies. Such is the price of hubris, etc etc etc.

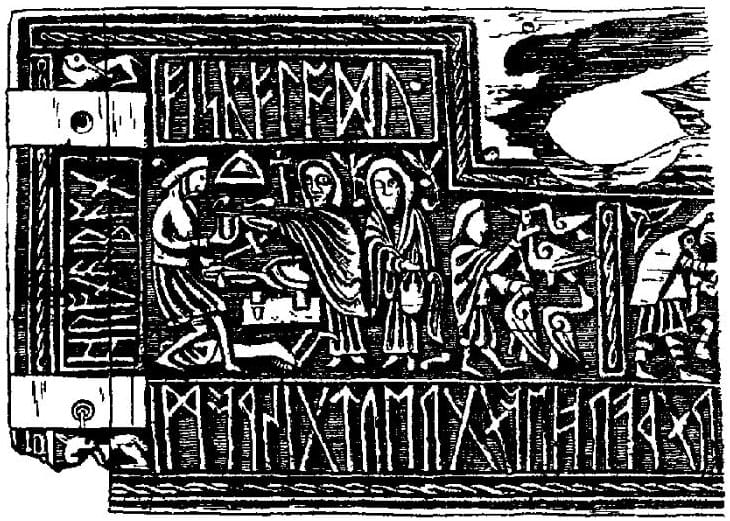

various portrayals of Weyland the Smith doing his thing: an 1848 print, the 8th century Anglo-Saxon Franks Casket, and his portrayal on Ardre VIII of the Swedish Ardre Image Stones.

A slightly less universally known story with similar winged-morality themes is that of the rather nasty medieval Germanic and Old Norse hero Wayland the Smith, a remarkably talented blacksmith and sometimes elven-prince. We hear a bit about him in the Völundarkviða, which is one of the mythological poems that comprise the medieval collection of surviving Old Norse literature known as the Poetic Edda.

In this tale, a character named Völundr (who is probably linked with the Germanic Wayland) and his two brothers are married to three mysterious vagabond women who have been described both as Valkyries and as swan-maidens. For unexplained reasons, the women leave again after nine winters to "fulfill their fate": while his two brothers depart to figure out what their supernatural wives are up to, Völundr stays home to make his own missing wife arm jewelry. Unfortunately, a local king captures and enslaves Völundr to take advantage of his remarkable blacksmith skills: to ensure he won't escape, the king cuts his hamstrings and imprisons him on an island.

While Daedalus found a non-confrontational mechanism for escaping from his captor, Völundr tackles the problem in a rather more, well, Viking sort of way. In this story, he kills the king's sons and makes jewels out of their eyes and teeth, gets the king's daughter drunk and seduces her, and then, by some unspecified mechanism, he rises into the air, flying away laughing his head off after he taunts both the king and his daughter one last time.

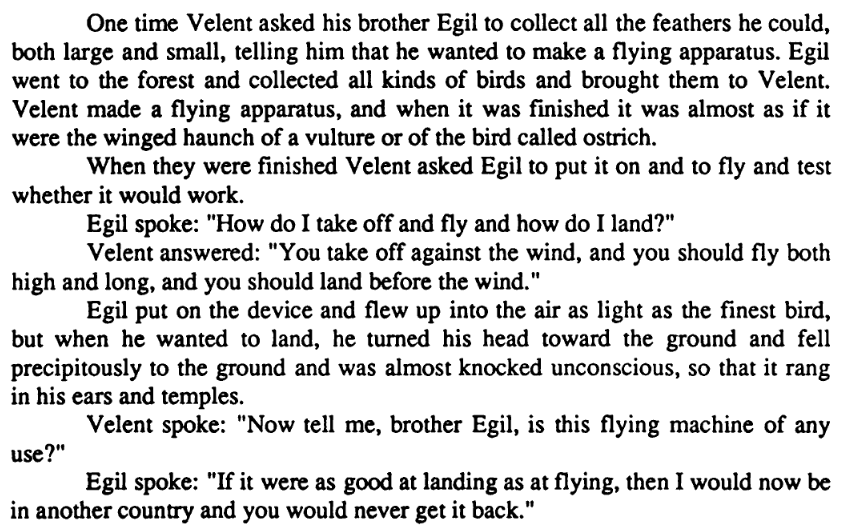

Another, much more detailed Old Norse version of this story comes down to us in the 13th century Thidrekssaga, which focuses on the German hero Dietrich von Bern but throws in accounts of the lives of a number of other medieval legendary figures for good measure. In this version, Velent (Wayland) works with his brother to craft feathers from various kinds of bird, constructing a flying apparatus that resembles the "winged haunch" of a vulture or an ostrich. The two men then engage in some surprisingly sophisticated discussion about magical flight dynamics:

In this version, the flying Velent/Wayland goes off to confront the king in the form of an extended monologue, which we can imagine him rather picturesquely delivering as he hovers creepily in the air outside of a tower:

So ends the story of Wayland, who uses his wings to triumph over his enemies - but not exactly in a pleasant way.

i love how King Bladud looks janky as hell in every single image I could find of him

Then there is the odd flight story of the legendary English King Bladud, a personage who renowned English historian/flagrant bullshitter Geoffrey of Monmouth introduced to the world in the 11th century: later English fabulists like John Hardying would proceed to embellish the story further during the 15th and 16th centuries.

Per these sources, Bladud lived around the year 850 B.C., was the father of the considerably-more famous King Lear (yes, the one from Shakespeare), and had taken power in ancient England via rather unusual means. As a youngster, he had been sent to Athens to receive an education. Unfortunately, Greece bestowed upon the young Bladud both knowledge and a ripping case of leprosy.

Initally upon his return to England, he was shut up in a leper colony, but he managed to escape, finding work as a swineherd. With little to do but stare at pigs all day, he observed that the muddy hot spring that his charges were wont to wallow in seemed to deliver them from skin diseases (of whichever god-forsaken kind pigs get). He dutifully started wallowing about in the muck himself, and lo and behold, his leprosy was cured. And thus did King Bladud decide to found the once-and-future hot spring resort town of Bath, where you can still take the healing waters today. Although the pigs have been evicted.

Not content to rest on his tourism laurels, Bladud then took up "necromancy," a term that was once used to generally describe somewhat dubious magical pursuits. Eventually, the intellectual hubris that these dark studies engendered in his heart led him to what medieval writers seemed to imply was a bit of an inevitable end-point: attempting to fly.

But let's permit John Hardyng - a man who wasn't much of a historian, but who could turn a nasty little phrase when called upon - take it away on the topic of Bladud's comeuppance:

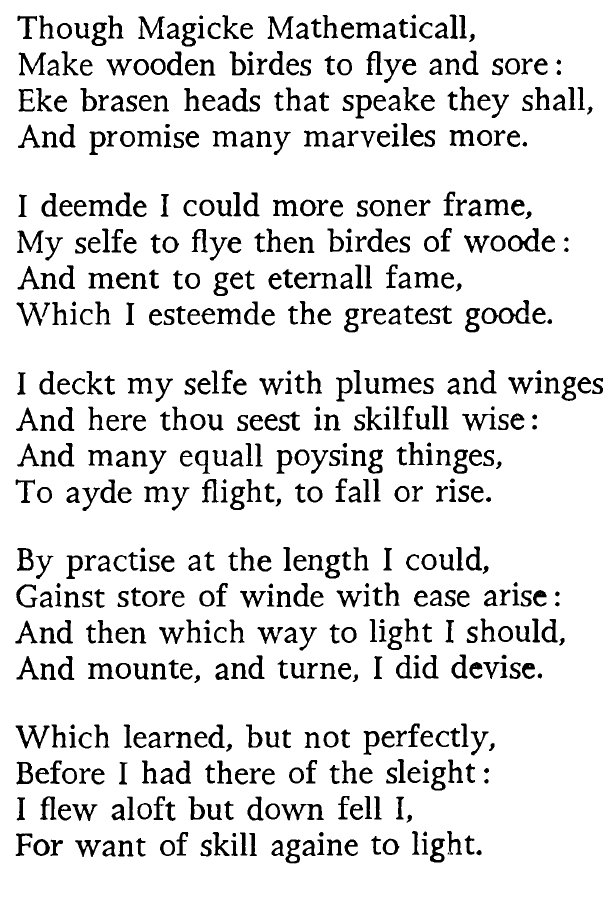

Bladud was further humiliated for his actions in the Tudor-period poetry collection entitled "The Mirror for Magistrates," in a classic specimen of Western literature's distrust of people who mess around with flying:

hah! got his ass!

Well, that all should have served as a stern warning to all those necromancers, wizards, and uppity academics out there about the dangers of attempting human flight.

But of course, it didn't.

While most stories about bird-men concern those who choose to fly of their own volition, another genre concerns the cruel actions of rulers who force men to fly due to some combination of genuine curiosity, religious motivation, and good-old fashioned sadism.

For one sterling example of the genre, we turn to how the Emperor Nero, history's most celebrated aristocratic sicko, allegedly used to force certain unlucky victims of his to "fly" for his own amusement.

The musically-inclined Nero was fond of staging elaborate entertainments, and among these were dances representing certain famous scenes and themes, performed by Greek youths who were promised certificates of Roman citizenship at the end of the show - if they survived, anyway.

The doomed flight of Icarus appears to have been one of these set-pieces, and as the Roman historian Suetonius rather archly writes:

Icarus at his very first attempt fell close by the imperial couch and bespattered the emperor with his blood; for Nero very seldom presided at the games, but used to view them while reclining on a couch, at first through small openings, and then with the entire balcony uncovered.

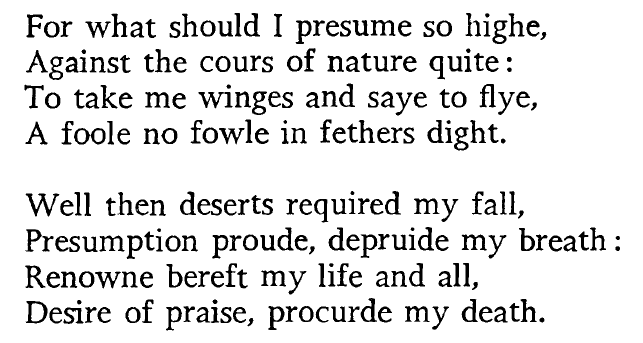

Meanwhile, the Latin poet Martial described a similarly perverse scene at the games of the Emperor Domitian, in which an unlucky man assigned to play the part of Daedalus tumbled into a pit full of hungry bears after his wings, inevitably, failed to carry him into the sky:

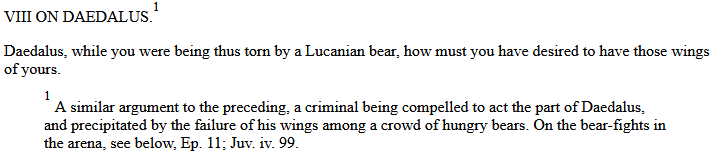

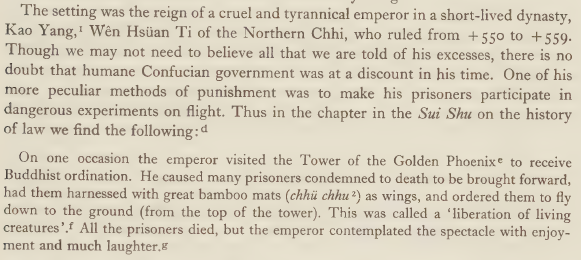

A ritual of similar nastiness allegedly took place during the miserable reign of the deeply horrible 6th century Chinese Emperor Wenxuan of Northern Qi, who was known personally as Gao Yang. It is described here by Joseph Needham, in his masterful and sprawling series (still ongoing today, after his death in 1995) titled "Science and Civilisation in China":

Another account of Gao Yang's actions casts these bird-man incidents in a more experimental, albeit equally cruel, light:

A far less cruel version of Gao Yang's experimentation took place in 19 AD during the reign of the Xin (or Hsin) Emperor Wang Mang, who was locked in battle with nomadic forces on the Chinese frontier to the northwest. Wang Mang decided that he needed a technological boost to beat these maddeningly persistent nomads, and so he mobilized all “who professed to be the masters of strange arts" within the realms of his kingdom. He then asked these luminaries to demonstrate their abilities before him, in an event reminiscent of a startup pitch meeting in today’s world:

This incident is especially interesting because it is an early example of humans imagining how useful it might be to gather information from the air. The bird-man’s attempt to spy on the enemy camps from the sky was by no means wildly unrealistic: he was merely many centuries too early to the punch.

We have always felt sort of amorphously weird about flying, in a way that is reminiscent of how we feel today about our modern suite of technological innovations, from social media to AI chatbots to, of course, drones. And yet, like so many of the things we feel amorphously weird about, our species doggedly persisted in trying to do it anyway. And eventually, we did manage to take to the skies in a far more practical form, and to a far greater extent, than most anyone of the distant past managed to imagine. Whether this was a good idea or not still very much remains to be seen. It is still early days.

In the next entry in this series, I'll dig into some of history's most simultaneously courageous yet impressively foolhardy aerial innovators: the succession of almost-certainly real people who flung themselves off tall buildings in pursuit of a very singular dream. Without them, we (probably) wouldn't have airplanes, satellites, or drones today. And we also would have far fewer entertaining stories.

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Preface

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: A Drone of The Mind

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Forgotten Technologies, Towers, and Roman Shitposting

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Death Rays, Brass Horses, and Dragon-Surprising Mirrors

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Pondering Orbs, Black Mirrors, and World-Viewing Cups