The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: A Drone of The Mind

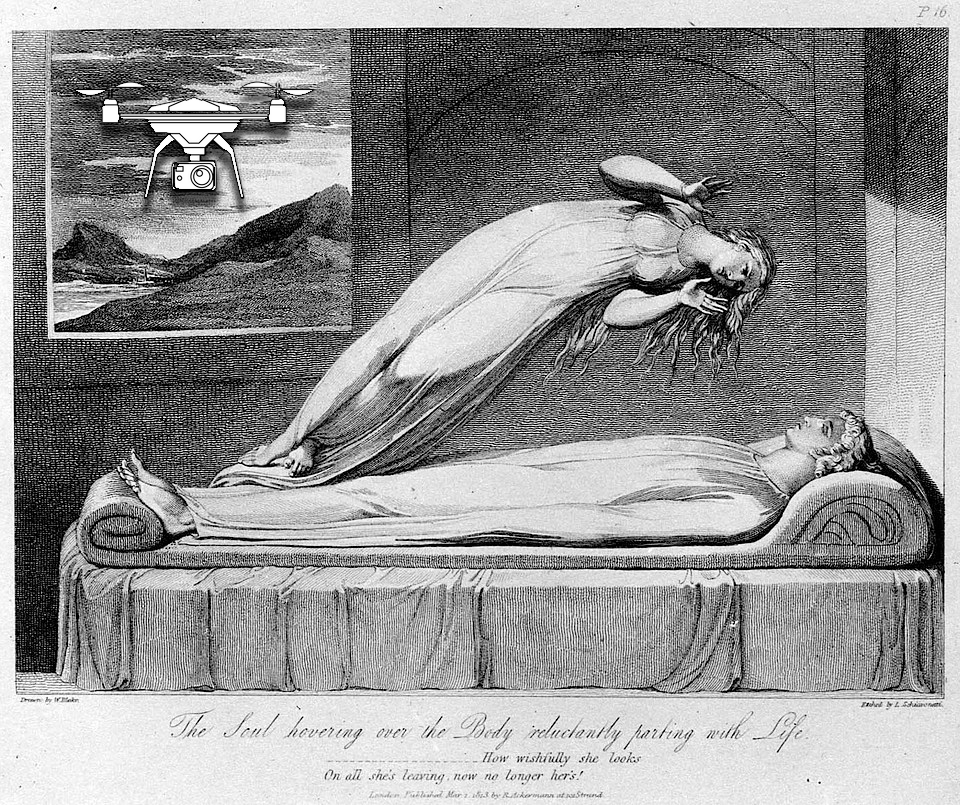

We have a body. We have a soul. It is possible to separate the two.

Usually, this happens when we die. But not always. Sometimes, the soul, and the ability to perceive that accompanies it, separates from our bodies for other, stranger reasons.

Throughout history and across cultures, humans have, in a very broad sense, largely agreed on these points.

When we invented drones, we created a technological means of allowing our souls to travel far beyond the fleshy enclosures of our bodies.

We mechanized a capability that was once thought to be exclusively reserved for shamans, gods, and demons.

We made it possible for the average person to, in a sense, astral project by means of a vehicle made of plastic and electronics, instead of in the borrowed body of an eagle, or in the unearthly rustling of a separated, gauzy shade.

We created a world in which this symbolism-laden device, this courier between realms, always goes on sale at Christmas - and a world in which, with a predictability veering upon ritual, these newly-minted pilots of the soul go forth and get their new cosmic vessel stuck way the hell up there in a tree.

While it may initially seem mildly insane to ascribe all this meaning to a toy helicopter with a camera stuck on it, consider this. How much opposition to drones is linked to people’s fears about being spied on by an unknown and unseen someone-else, in a way that somehow feels more creepy than being perceived by a human being in a manned aircraft?

Intuitively, most of us seem to understand that drones are not just machines, and that they occupy somewhat stranger metaphysical territory than the average generator, pickup truck, or power-washer. While the drone's pilot may remain firmly planted on the ground, a little bit of them is up there in the sky too - a connection maintained not by telepathy or magical forces, but by means of remote control technology and a smartphone's live feed.

This, then, is the first dream that humanity had to have before we could build a drone - the dream of far sight. Of being able to look upon the world from perspectives far beyond our ground-dwelling eyes. Of being able to split our perceptions from our presences, and to wander the earth as two things at once.

In the first century AD, the ancient Roman author and naturalist Pliny the Elder wrote, in an entirely scientific tone, about the curious habits of a certain Hermotinus of Clazomenae, whose soul was:

in the habit of leaving his body, and wandering into distant countries, whence it brought back numerous accounts of various things, which could not have been obtained by any one but a person who was present. The body, in the meantime, was left apparently lifeless . . . . At last, however, his enemies, the Cantharidae . . . burned the body, so that the soul, on its return, was deprived of its sheath, as it were.

While this story from Pliny didn't end well for Hermotinus, it points at the evident antiquity of human ideas about souls, bodies, and the prospect of the two ambling off in different directions under certain circumstances. We are a species that has long been attached to what's now called mind-body dualism- the notion that the mind and the body are distinct things, as articulated formally in more modern times by Rene Descartes and by a host of subsequent philosophers.

In the 21st century, most people still generally agree that something like this distinction between the mind (or soul) and the body is going on, even as the medical industry makes great strides in better understanding the endless, maddening ways in which our minds and our bodies intersect to impact our physical health. A 2013 Harris poll found that 64% of American respondents believed in the survival of the soul after death, while a 2016 Pew Research survey found that a majority of people in Western European countries believed that they possessed both a soul and a physical body.

At the same time, new age spiritual practitioners have been writing books and teaching workshops about the intriguing possibilities of astral projection and out-of-body experiences since at least the 1700s. More recent astral projection enthusiasts include the the now-deceased "Jurassic Park" writer Michael Crichton, who wrote a popular book in 1988 about his travel experiences on both the physical and astral planes. And while we currently live in an era of virtual reality headsets, incredibly immersive multimedia, and well, drones, public interest in more spiritual means of exploring the separation of body and mind appears to be more robust than ever.

As I write this in 2025, over 340K people are members of Reddit's Astral Projection community, where users swap tips about achieving the requisite mental state required to transfer "awareness to NON-PHYSICAL realities in order to explore BEYOND the physical." Across the modern world, spiritual centers offer astral projection workshops, while TikTok and YouTube overflows with helpful videos offering to teach the public how to spiritually explore beyond the confines of their bodies.

While it's obvious that most people continue to adhere to some form of dualistic thought, debate over its accuracy also still rages among philosophers, technologists, and other assorted nerds to this day. This conversation has been given particular recent animation by the hype-cycle obsession over what venture capitalists like to call artificial intelligence - a fixation that features a lot of fervent LinkedIn posting about if it's possible for human engineers to create a human-like artificial general intelligence that can exist without the vessel of a fleshy, mortal sapient form. Or perhaps, could be stuffed into the artificial vessel of a drone.

But let's not get ahead of ourselves, into the dystopian and disembodied future. (God knows we hear enough about that already).

Today, in this post, I'm talking about the drones of the mind of the past.

Humans largely agree on dualism, and we also, for some reason, seem to largely agree that when someone's soul detaches from their body, it is usual, and preferable, that it goes up.

Across the world, many people take great solace in the notion of dead loved ones and friends “looking down” upon them from the heavens as they go about their earthly business, in a form of extremely welcome aerial surveillance - a concept that pops up in everything from the most solemn of religious literature to Disney's Lion King movies. (People also like to think that The Police's endlessly-replayed 1982 "Every Breath You Take" is a sweet song about someone looking down from heaven on a loved one, but surprise, it's actually about a possessive stalker!).

In literature, film, and video games, the notion of a dead person's soul springing up from the body and flying up into the heavens is so totally cliche and commonplace that it can be a struggle to notice that it's there at all. Conversely, albeit less frequently, we also see frequent media portrayals of the souls of terrible people being sling-shotted downwards into the sunless depths of hell.

And these ideas about the relative vertical direction of the soul after it detaches from the human body have been rattling around in our collective consciousness for a very, very long time.

Ancient Chinese sources dating back to the middle of the 6th century BCE divided the human soul into an earthly aspect (po) that came into being upon a person's birth. As the person grew, the po would eventually be joined by a more heavenly aspect of the soul, known as hun. The character for “po” can be translated as “bright light” or “white,” and can be described as a human’s overarching life principle. “Hun” meanwhile, is a wandering spiritual and intellectual aspect of the soul, connected with notions of un-resting flight and with links to ancient words for clouds and mist.

Per these Chinese beliefs, when a person died, the more spiritual hun part of their soul would flow up into the heavens. Meanwhile, the po part would stay with the body after death, slowly dissipating downwards toward the ground. Along these lines, the beautiful green jade burial suits created for Han Dynasty elites may have been designed as a sort of elaborate spiritual Tupperware, intended to slow the rate at which the po oozed out of the body.

To return to the West, the Classical Greek philosopher Socrates claimed in Plato’s Phaedo dialogue that humanity dwells in a hollow place far below the true surface of an immensely vast and spherical earth. We are, in his world-view, equivalent to the dark-dwelling angler-fish and toothy eels of the ocean’s depths, totally unaware of the other light-filled world that lies far above their geothermal-vent filled homes.

And indeed, far above the realm occupied by us wretched slime-emitting beasts, there exists the "true earth," which is occupied by a superior and graceful people who float amongst air and ether, and who can communicate directly with the gods.

When people in our shitty, nasty realm who have lived lives of "surpassing holiness" die, they are benevolently permitted to ascend to the surface of the “true earth,” where they will exist forever as disembodied, obnoxiously morally superior beings. As you can probably predict, the souls of the immensely bad are hurled into the underworld of Tartarus, while the souls of the merely mediocre (ouch) are punished for a bit in the underworld, and then returned to the earth again.

This returns us to our general, mostly-universal theme across human societies: preferably, souls go up when they're detached from the body, but they can also go down. And you really won't like what happens when they do.

When you're talking about human ideas about dualism, separated souls, and verticality, you also can't ignore all the stuff in human tradition about birds.

Many global traditions link birds both with notions of freedom and the passage of the soul upwards, into the sky. In some cultures, people believe, or used to believe, that the soul explicitly turns into a bird after death, such as an old-time belief among seamen in Ireland and Great Britain that storm petrels were the flitting souls of dead sailors who perished at sea. Some European traditions once held that ravens housed the souls of the unbaptized, in a neat example of Christian beliefs that have merged elegantly with folk ideas that likely date back much further in history.

In other cultures, birds are given the specific job of conveying souls upwards after a person dies - functioning as "psychopomps," guides for the souls of the deceased. In this guise, birds function as bridges between the earthly world of the living and the upper atmosphere of the spiritual and the perished.

Perhaps, in the fullness of time, we'll start thinking of the souls of our deceased relatives being borne to the heavens by a flock of sanctified, whirring drones.

Of course, you don't have to actually die for your soul to be separated from your body.

Consider the inherent high weirdness of what happens when we dream. Our bodies are parked in our beds, but our brains and (in theory) our souls are flying above the earth, or, less dramatically, showing up to the office nude. Every night of our lives, our brains generate these distinctively dualistic experiences for us - a constant reminder that human consciousness can extend beyond the confines of the body. Or at least, can rather convincingly appear to.

It's hard to say why humanity has come up with so many interesting ideas about what a human soul (or mind, if you'd prefer that term) might get up to while the body is otherwise occupied. But if I had to guess, our universally-shared experience with the disembodied experience of dreaming may have a lot to do with it.

Japanese literature has spoken of the Ikiryō or “living ghost” since at least the publication of the “Tale of Genji” in the year 1000, by the great Heian-period author Murasaki Shikibu.

These spirits are usually, albeit not always, powered by an attacker with a deep-seated grudge: under these especially hate-filled conditions, the perpetrator's soul departs the body and flies off to harass the victim. One section of "Genji", considered to be history's first true psychological novel (and one of our oldest surviving literary works by a woman), describes how the eponymous hero’s devious and very-much-alive lover knowingly “projects” her spirit to torment his wife, killing her after she gives birth.

In a story from the 1663 Japanese horror collection Sorori Monogatari (曾呂利物語), in the amusingly titled chapter, "A Woman's Wild Thoughts Wandering Around," a man traveling alone on a dark and creepy road mistakenly thinks that he has spotted a chicken in the bushes. To his abject terror, he realizes that he is in fact looking at the disembodied and horrifically agile floating head, or nukekubi, of a woman.

Entirely counter-intuitively, the man angrily pursues the leering head all the way back to a house in Kyoto, where he discovers that it belongs to a very-much-alive and extremely surprised housewife - a person who has deployed her ikiryō unintentionally and without harboring ill-will. For the housewife's part, she has just awoken from a truly awful dream about being chased by a man with a sword.

Another example of this type of soul-travel comes from a 17th century Chinese account of the life of the Daoist immortal Han Xiangzi, a spiritual hero who has been a fixture of Chinese popular culture since at least the Jin and Yuan dynasties of the 1200s. In one portion of the book, Xiangzi is repeatedly kicked out of the palatial home of his unpleasant uncle, a privileged Confucian who has little use for his nephew's pointed critiques of the wealthy - much less for his nephew's request (on behalf of the mighty Jade Emperor) that he leave his riches and take up an ascetic, holy life.

Whenever Xiangzi is booted out, for admittedly annoying acts like "summoning a talking goat, taking it away again, and accusing his uncle's female relatives of secretly being wolves by means of a really nasty song," he simply lies down and starts snoring.

And then Xiangzi uses his spiritually-endowed ability to project a sort of secondary "shadow body," or "primordial spirit" to let himself back in.

It's the Daoist version of that eternal Simpson's meme in which Moe throws Barney out of the bar, only to see Barney inexplicably coming up behind him a moment later.

These stories represent a few of the mechanisms by which the human soul can travel on its own separately from the body, both intentionally and unintentionally. But sometimes, the only way for an adventure-loving soul to hit the road is by hijacking. Or, to put it more pleasantly, by means of rental.

Some traditions imagine that, as living people, our souls can not just travel - but can also possess the body of someone else in the process. Then, the soul-traveler can "see" through that other-body's eyes and control where it goes and what it does, just as I "see" through my drone's mechanical eye via the live video feed it delivers my mobile phone, and tell it where to go and what to do.

In our modern cultural context, perhaps the closest idea to this second form of the "mobile soul" as practiced by a still-alive person is represented in Game of Thrones, where the wheelchair-bound character Bran transcends his physical limitations by taking possession of the bodies of animals, and, on one nightmarish occasion, the body of a human being.

He controls their bodies and "sees" through their eyes: horrifyingly enough, he can turn everything alive into a sort of "drone" if he wills it. Indeed, all organisms in his grimdark fantasy world can be seen as potential extensions of his body - functioning as unwilling eyes and fingers through which he can see and touch the earth.

But of course, George R.R. Martin wasn't the first guy to come up with this idea.

We're pretty sure that it goes way back.

And one of our richest sources of ideas about souls traveling around and occupying the bodies of others comes from the incredibly varied set of global religious beliefs that we all-too clunkily lump together under the term "shamanism."

According to author and researcher Manvir Singh a shaman can be defined as "a specialist who, through non-ordinary states, engages with unseen realities and provides services like healing and divination."

What does that look like in practice?

Per the world religion expert Margaret Stutley, shamanistic traditions share three particular beliefs in common.

The first is belief in the existence of a separate world of spirits, a parallel realm that is capable of acting, for good or ill, upon the affairs of humans. These beliefs often overlap with animistic religious ideas, which hold that both animate and inanimate objects – animals, rocks, trees, and the like – all have souls. Shamans thus set themselves apart as rare human beings that are capable of communicating with the spirit world, a function that they perform on behalf of both their community and on behalf of humanity as a whole.

Secondly, the shaman often works to treat disease and ill health, often of a spiritual or not-exactly physical sort. They “not only control the ecstasy of their own souls but specialize in the knowledge and care of other’s souls, as well,” writes anthropologist Lawrence E. Sullivan.

Third, and most relevantly for our focus on drones, shamans are specialists in the travel of the soul.

For shamans, soul travel usually requires more up-front preparation than merely falling asleep, or really, really hating somebody.

To enter the spirit world and to "free" their soul to wander beyond the confines of the body, shamans must first enter into a kind of trance state via singing, dancing, mind-altering substances, or some combination therein.

Once properly detached, the shaman's soul is capable of roaming both the earth and spiritual world, in search of knowledge and superhuman insight. This ability is a special privilege: per these traditions, unique among humans, only the shaman’s “free soul can transcend the boundaries of the dead without risking his life.”

In many traditions, the shaman performs this spiritual travel by means of possessing - or less aggressively, sharing - the body of someone else, usually an animal "helper spirit" that the shaman feels a particular affinity with. While soul-travel with the assistance of an animal vessel is common, some shamans are also believed to be able to "project" their souls beyond their bodies in a non-tangible, or at least less representational, form. Finally, the shaman's trance-state can be a two way street: spirits from other realms also may occupy the body of the shaman, using their human form as a medium for communication.

Frequently, shamans embark on these journeys of the soul to protect and to guide the souls of the living, carrying out a key responsibility that comes with their usual special status as healers and protectors of the communities.

When someone is close to death, some cultures believe that the afflicted person’s soul has effectively been held captive by demons or other malevolent entities in the spiritual world. Operating as a spiritual sheep-dog, the shaman thus deploys their own soul to search for the victim, embarking on a sort of metaphysical search and rescue mission. In this fashion, the shaman does battle with the demons holding the entrapped soul hostage. If they win the fight, they're permitted to return home with the captured soul: if they lose, the afflicted person dies.

It's something of a high-pressure occupation.

In all shamanistic traditions, the practitioner occupies a sort of “double consciousness,” in which they simultaneously exist both in the knowable world and in the spiritual world - straddling multiple realms while not fully abandoning either, functioning as a mediator and guide between the two. This shamanistic ability to exist in two worlds at once may initially sound rather exotic.

But arguably, we actually place ourselves in a state of double consciousness all the time. By which I mean "using the Internet."

Somehow, I can be sitting at my computer in my home, and I can also be shit-posting on the Internet, declaring my presence in an abstract online locale that still feels very real to me. And I do this all the time, flitting constantly between the material world of my physical experience and the secondary, shadow-world of digital communication. I just happen to be engaging in this constant act of dual consciousness with the help of an electronic device, instead of by means of cultural ritual or mind-altering substance.

While most people don't think of the Internet in terms of double-consciousness, you can absolutely see echos of this in how we talk about the Internet, and where our societal fears and anxieties over its all-pervasive nature lie. We're still in the midst of society-wide debates over if what happens on the Internet is actually real, or if it's actually fake, or if our activities online occupy a strange and often dangerous liminal realm somewhere in between.

Drones, arguably, take this state of digital double-consciousness a step further.

Unlike my smartphone and my laptop, they can move around. When I'm flying a drone, I'm planted firmly on the ground, and I'm also observing what the machine “sees” as it physically flies through space. I can digitally project my consciousness and my perceptions not just via the medium of an easily-ignored post, but through the vessel of an actual, flying object.

In this way, drones take our existing deep ambivalence about the inherent, constant weirdness of being able to be in two places at once via the medium of the Internet, and make that lingering discomfort considerably more visual. More tangible.

Perhaps a key reason why people are afraid of drones is because they are an uneasy reminder of how the Internet is continuing to ooze out into the real world - of how technology, and the unknown people controlling it, can come looking for us when we want nothing to do with them.

And perhaps that entirely modern fear of an unknown realm of hard-to-understand forces leaking over into our own world is linked way back in human history to more ancient anxieties.

Anxieties - once addressed by shamans, and other spiritual practitioners, and now largely left twisting in the air - about what could happen when the unpredictable and largely incomprehensible spirit world spills over into our own.

Most shamanistic traditions are intricately connected to the animal world, operating in a world view in which animals are imbued with spirits - just as human beings are. Shamans bridge the gap between human and animal both by means of communicating with their spirits and (sometimes) by physically occupying their bodies.

In the so-called heartland of shamanism in Siberia, certain traditions say that shamans, by virtue of their “free souls,” can perform rituals that allow them to incarnate their own souls (or "kut") within certain animals. Sometimes, these animals can merely serve as assistants for the shaman - however, these animals may also act more independently as spiritual advisors, with minds and agendas of their own.

Often, these spirits take the structurally convenient form of birds, a vessel that helps the shaman truly embark on a “flight of the soul.” A shaman whose “helper spirit” is an eagle, writes anthropologist Marjorie Balzer, is therefore lent the “all-seeing pivot eyes” and “piercing eyesight” of the bird.

In one story related to Balzer by her Yakut interlocutors, a shaman known as Parilop has a close call while sharing the body of one of his helping spirits, a woodgrouse:

"One day Parilop decided to visit his friend Kharkha in the village of Khatingnaakh. He came as a woodgrouse and sat right on Kharkha's roof. Kharkha came out of his house, saw the woodgrouse looking at him, and grabbed his gun, ready to shoot the bird, who got away." In a few days, Parilop arrived by plane. He "went to Kharkha's house, somewhat miffed but smiling, and said 'You nearly shot me the day before yesterday. Why did you try to do this?'”

While Siberia may be widely considered to be shamanism's so-called heartland, similar traditions related to soul-travel pop up in a remarkably wide array of cultures around the planet.

Certain cultures in the Brazilian Amazon also believe that shamans have mobile souls, which can transform into the shape of birds and other animals. Much like in the Siberian tradition, this animal form usually retains a certain sense of separation from the shaman's own soul, functioning as something of a helper, or a guide.

In some of these Amazonian cultures, shamans turn to hallucinogenic substances like yage – more popularly known today as ayahuasca, a barf-inducing darling of today's insufferable Silicon Valley set – to induce a sense of spiritual flight. While it's unclear if ayahuasca consumption is actually an ancient tradition in the Amazon (or at least, in the way most tourists think it is), we do know that people have been using substances to induce spiritual states around the world for a very long time.

In the Vedas, one of the planet's oldest religious texts dating back to the 1st or 2nd millennium BC, the writers describe the ingestion of soma, a hallucinatory beverage that could produce the impression of flight, making the drinker feel like a bird. Under its influence, they could then travel the world of the gods and obtain sacred knowledge.

To return to South America, an account from Villavicencio, a 19th century Ecuadorian geographer, a certain group of Amazonian people told him that the yage causes them to "feel vertigo and spinning in the head, then a sensation of being lifted into the air and beginning an aerial journey," above a mysterious, terrifying landscape that they (or their consciousnesses) view from an elevated, rather drone-like position.

Among the Tapirapé people of Brazil, shamans are believed to be capable of traveling to the villages of the dead by transforming into a bird. In this shape, they are also able to recover the “lost” souls of other people, including the souls of yet-to-be-born children.

Shamans amongst the Akawaio Carib people of British Guiana induce their form of spiritual trance by chewing tobacco, after which they believe that the shaman’s soul shrinks and becomes light - so light that it is able to more readily detach from their body and ascend into the skies. The shaman's soul then moves upward with the assistance of a series of “ladder spirits,” most notably that of the swallow-tailed kite (a bird that is interestingly referred to as “clairvoyant woman” in the Akawaio Carib's own language). Meanwhile, as the shaman's soul ascends into the heavens, their currently-unoccupied body is temporarily taken over by opportunistic forest spirits.

According to the Batek Negrito people of Malaysia, all humans have a personal “shadow-soul," which can separate from the body to speak with spirits in dreams. As shamans are more powerful than the average person, they can communicate with the so-called hala' asal ("original superhuman beings") by entering a trance state and “steering” their shadow soul – guided by songs – to any place in the universe that they choose. While the shaman’s shadow-soul often has a particularly workaday purpose in mind as it travels to the realm of this spirit or another, it can also engage in a bit of transcendental tourism. At times, it “just travels about, marvelling at the wonderful sights.”

To the Mapuche people of Chile and Argentina, shamans are known as “machi,” and these spiritually powerful people form particularly close spiritual bonds with animals. They essentially “share personhood with shamanic spirits who possess them and who grant them healing powers and insights into the past, present, and future,” according to the anthropologist Ana Mariella Bacigalupo.

At times, the human body of the machi and the body of their machi animal can even become essentially interchangeable, with intertwined fates: the animal can become sick on behalf of the machi, and so too can the machi become sick or die if the animal is maimed or killed. When a Machi dies, the community kills their machi animals as well. This is done in the hope that the animal’s spirits will traverse the Wenu Mapu, the “Mapuche sky," with them for the rest of eternity.

In some cases, in some shamanistic traditions, people believe that objects can occupy the body of human beings.

In an account from the anthropologist Elizabeth Colson, a woman from Zambia's Tonga culture was (understandably) shocked to see an airplane flying over her village in about 1954, an experience so startling that she fell into a "sort of swoon."

After this took place, the woman reported that she believed that she had been entered by a spirit called Airplane (or indeki in her language), and that this airplane-spirit demanded she provide with drumming, songs, and dancing. To placate the spirit, she crafted a special dance for it, and taught the dance to others. Soon, some other members of her village began to dream regularly of over-flying airplanes, and felt that they had been possessed with the “airplane spirit” themselves.

This Zambian woman was not alone in believing to at least some extent that objects can contain spirits or souls - spirits possessed of their own free will and desires.

Which leads me to a crucial point: shamanism isn't dead, and it's not primitive. Shamanistic beliefs are very much alive in the 2020s, and in many cases, these belief systems are simply adapting to our ever more technology-saturated societies.

City-dwellers from Tungus-Manchu cultures in North-eastern Asia and Siberia now report, according to this paper, that their cars, phones, and laptops “behave” as if they have been possessed by spirits, just as their ancestors might have assumed that spiritual possession was responsible for the freakish behavior of a tiger.

“If a spirit settles in a car, that car can go crazy, refuse to work, or run on its own. The technological devices can gain their own will and go not where a human sends them but where they themselves want,” explained one Tungus-Manchu interviewee to a researcher in 2003.

For me, an American city-dwelling dork with no shamanistic background whatsoever, I find the ideas expressed by this Tungus-Manchu person to be highly relatable. They are concepts that confirm certain creeping suspicions I have long held about the technological world I exist in.

Have you ever wondered if your laptop was possessed by malevolent and dark forces, as it snaps on at 2:00 AM in your bedroom? Have you ever shouted foul profanities at your car?

These fears of spiritual intervention in the freaky behavior of one’s technology works particularly well for drones, which are, after all, engineered explicitly to be able to make some computerized decisions “on their own.” Much like the animals that many shamans affiliate themselves with, they are steered by humans, yet at least appear to have strange agendas of their own.

They're machines that we all know come pre-loaded with ghosts.

I have watched drones zip spontaneously towards a power line, as the pilot howls in anger and surprise. Probably there has been some error in programming, some algorithmic cock-up. But even the engineers often have no real idea of what went wrong, or why it happened at that specific disastrous time.

We can blame it on the spirits.

Here are the entries in this series so far:

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Preface

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: A Drone of The Mind

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Forgotten Technologies, Towers, and Roman Shitposting

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Death Rays, Brass Horses, and Dragon-Surprising Mirrors

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Pondering Orbs, Black Mirrors, and World-Viewing Cups

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Tower-Jumpers and Hungry Eagles