The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Concerning Eyeballs, Spiritual Surveillance, and Odin's Ravens

In modern times, we have democratized the formerly inhuman god's eye view.

We have extended to everyone the steely gaze of a god peering down upon the activities of mortals from a celestial perch, or the exalted viewpoint of an emperor regarding his holdings from the vertical fastness of his pyramid.

Specifically, you can buy this exalted perspective for $300 on sale at Christmas.

With a drone, we can become just a little bit superhuman.

Once, long ago, only the gods could truly gaze down upon the earth from above, casting their far-seeing glance on any place or person that they chose.

Mere mortals could only approximate this experience, by means of climbing way up onto a mountain and dreaming about what it'd be like to view the world from an even higher and more extended perspective.

And dream, they did.

While pre-modern humans lacked tools for actually doing remote sensing, they still thought frequently and deeply about what it might look like in practice. They were also well aware of how interested parties could use a combination of subterfuge and intimidation to monitor, and thus exert power over, the lives and relationships of both their subjects and their peers.

And while most people of the past assumed that these powers were and would remain restricted only to gods and deities, we can trace the conceptual roots of modern technologies for far-sight, like drones, all the way back to the old stories that people used to tell each other about superhuman perception, and the dangers that might accompany it.

When you think of the god's eye view, and the general concept of mighty deities staring down upon the earth, you probably imagine something a bit like Disney's 1997 "Hercules" animated movie. You are likely envisioning a bunch of gods lounging around on the pillowy clouds that congregate around the peak of Mt Olympus, in a sort of celestial country club in which they spy upon the affairs of mortals and occasionally hurl a lightning bolt at the naughty ones. Also, there's gospel music playing in the background for some reason.

This pop-culture representation (minus the gospel music) can be traced back all the way backwards in time to the stories of Homer, who frequently describes deities like Zeus and Poseidon keeping superhuman tabs on the affairs of mortals from mountain tops and from the far-off heavens.

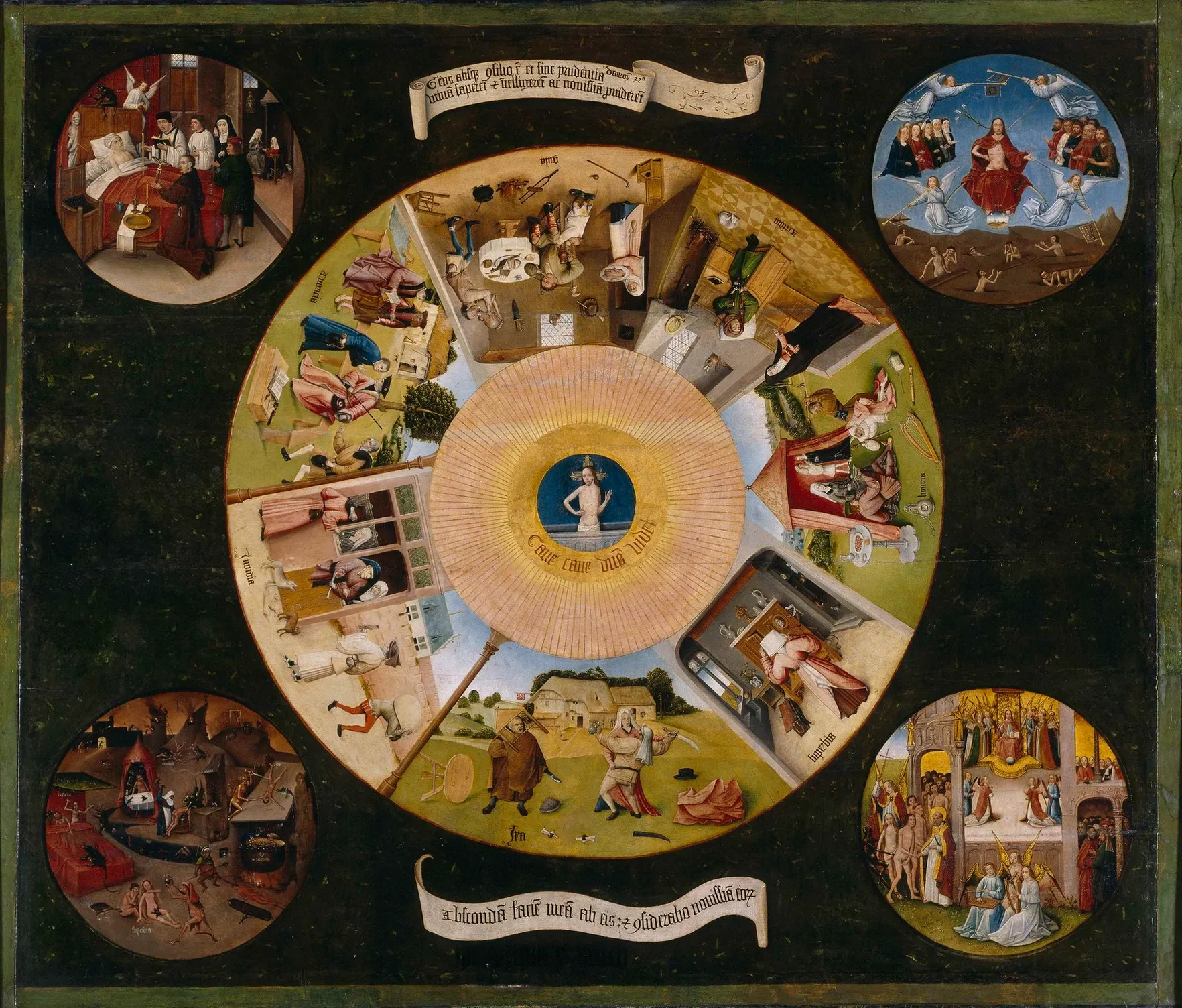

This notion of an omniscient deity constantly watching from above in order to keep us unruly, scampering little mortals in line has proven to be remarkably durable, persisting in this general format into many religious traditions into the present.

Psalm 139 of the Christian Bible (which Jeremy Bentham himself referenced in his book on the Panopticon) is directly concerned with God's constant and omnipresent surveillance of not just human activities but also human minds:

You have searched me, Lord,

and you know me.

2 You know when I sit and when I rise;

you perceive my thoughts from afar.

3 You discern my going out and my lying down;

you are familiar with all my ways.

4 Before a word is on my tongue

you, Lord, know it completely.

5 You hem me in behind and before,

and you lay your hand upon me.

6 Such knowledge is too wonderful for me,

too lofty for me to attain.

Christians frequently say that the Lord is watching over them, a relationship that they view as a positive expression of the deities love for them, his concern for their welfare and their spiritual development. [[1]]

This point is important to remember, in our current dystopian shit-show of a decade: it is certainly still possible to imagine a type of surveillance, or god's eye view, that is paired with an ethic of care for its subjects, rather like an observant and loving parent. Arguably, my own career has been devoted to this very concept, by means of my work on using drone imagery for socially-beneficial purposes, like disaster response and public transit research.

However, for Christians, the implied comfort of God's constant observation of their activities is constantly and irrevocably paired with the equal knowledge that He will also be instantly aware whenever they fuck up, and that they will be required to suffer the consequences. To this day, children around the globe are still imbued with the anxiety-inducing idea that they must behave correctly at all times, because even if their actual parents aren't watching, God always is. [[2]]

In other words, the Good Lord's far-ranging eye giveth, and it also taketh away.

The eyes of God have taken many strange and divergent forms over the course of human history.

Often, across many cultures, the human eye was symbolically linked with divine or supernatural powers of hyper-vision. We can trace it all the way back to the staggeringly old societies of Mesopotamia, the likely source of the still-popular concept of the evil eye, a demonic, beholding influence that wrecks havoc upon human affairs. The ancient Egyptians used the more positively-perceived symbol of the eye of the sun god Horus on everything from amulets to tomb walls, while the old Minoan script used the symbol of an eye to describe an overseer or a supervisor - someone who "sees particularly well and also exercises power."

Powerful beings with superhuman powers of sight pop up in the Mayan Popol Vuh, which describes the supreme gods creation of a race of proto-people who can "behold everything" instantly and who "did not have to walk to see all that existed beneath the sky": their knowledge is so immense that the gods grow distinctly uncomfortable with the experiment, and decide to take it back. (The Maya continue to believe that properly-trained priests and shamans can tap into this far-sight ability).

These stories largely concern beings endowed with the customary number of eyes. But there is another genre of old tale which explores the possibilities of having lots of them.

The Hindu Rig-Veda is one of the oldest known texts in any Indo-European language, and its earliest portions quite possibly date as far back as the 2nd millennium BCE. One of its ancient Sanskrit hymns tells the story of the unfathomably gigantic being Purusha, who existed before the beginning of all things, and observes all things:

“A THOUSAND heads hath Puruṣa, a thousand eyes, a thousand feet. On every side pervading earth he fills a space ten fingers wide.This Puruṣa is all that yet hath been and all that is to be;The Lord of Immortality which waxes greater still by food.”

Along similar lines, Zoroastrians still venerate the deity Mithra, who is described as having "ten thousand eyes, is tall, has a wide outlook, is strong, sleepless, (ever) awake." The ancient Visayan society of the Philippines worshiped the many-eyed goddess Dalikmata, who used her largely benevolent powers of surveillance and clairvoyance to monitor and guide the villagers who served her.

In the Hebrew Bible's Book of Ezekiel, we come across the prophet's vision of biblically-correct angels, or ophanim, who are accompanied by shining gyroscopes: "their entire bodies, including their backs, hands, and wings, were full of eyes all around, as were their four wheels."

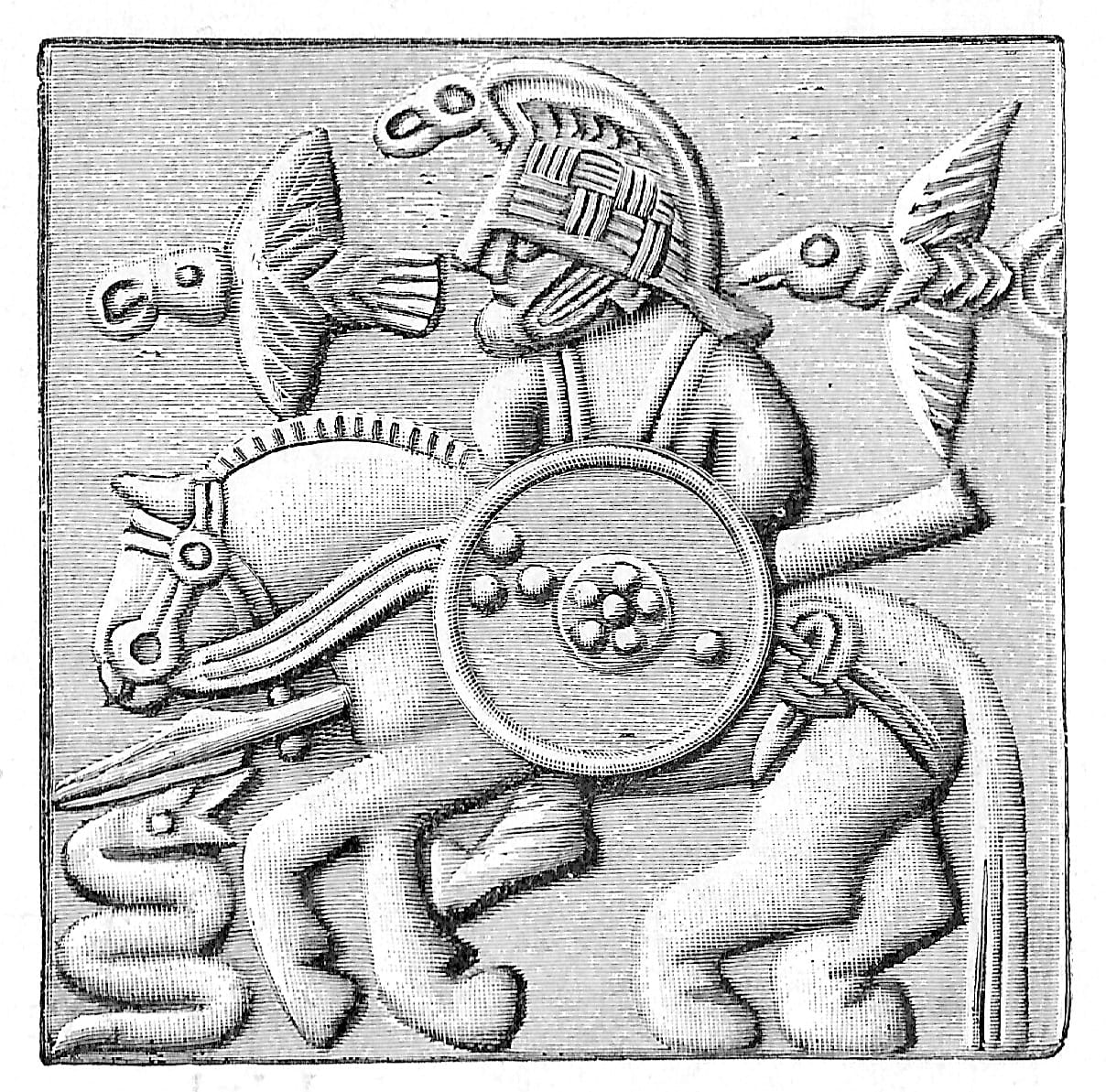

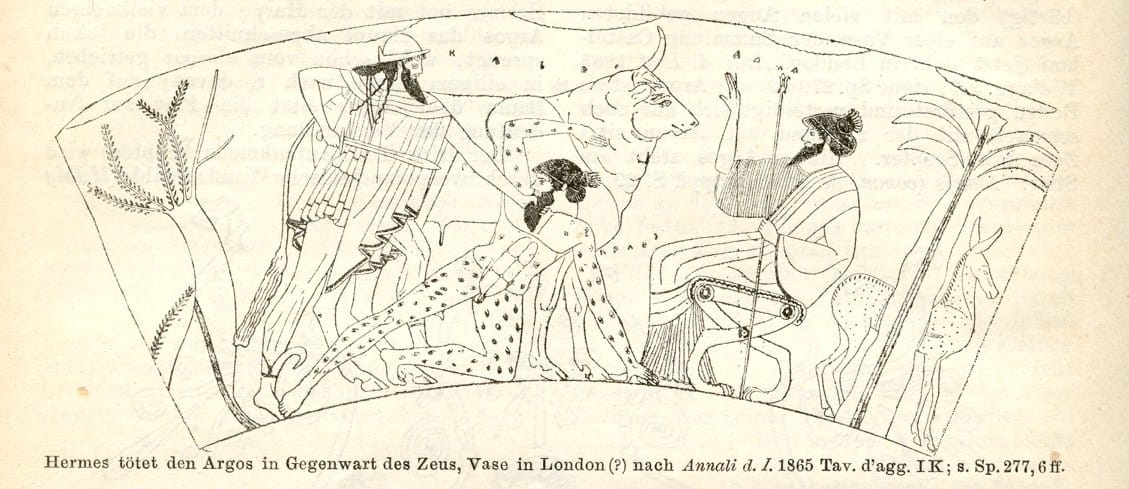

In the ancient Greek context, we encounter one particularly famous deity with a whole lot of eyeballs: the formidably all-seeing Greek giant Argus Panoptes. (And yes, Jeremy Bentham was thinking of him when he came up with the term "panopticon.").

The old Greek term “panoptes” translates to “all-seeing." In more practical terms, surviving stories from the ancient world place Argus's actual quantity of eyes at anywhere to four to over a hundred, and the relative nastiness of the mental image this evokes scales up in the same way. (Let me ask the hard questions here: did he have eyes on his butt?).

As the myths have it, Argus was a valued employee of the powerful and capricious goddess Hera, who oversaw matters related to women, marriage, family, and childbirth.

Unfortunately for Hera, she was also married to the aforementioned and legendarily slutty Zeus, who spent much of his time - when he wasn't observing the affairs of mortals - gallivanting around the world transforming into animals for uncomfortably erotic purposes.

Hera tasked Argus with using his remarkable, upsetting visual gifts to keep tabs on Zeus's zoologically-oriented romantic activities. Most importantly, Argus was in charge of stopping Zeus from boinking a cow.

Once, the cow in question had been a human girl of noble origins named Io, who served as one of Hera's priestesses. In that precious, pre-cow interval of Io's life, Zeus - as was his wont with basically anything with a pulse - fell in love with her. Hera was angry about this act of infidelity, so Zeus decided to transform Io into a fetching white cow to protect her from his wife's celestial rage. (It is unclear what Io thought about this).

Countering her mighty husband's strategic move, Hera asked Zeus to give her the-heifer-formerly-known-as-Io a a present, and he grudgingly complied. Wisely unwilling to trust her husband, Argus tied Io to an olive tree and charged Argus with keeping a close eye on her.

Zeus swiftly tired of being kept away from his bovine sexual conquest by the ancient equivalent of a home security Ring camera, and tasked the messenger God Hermes with neutralizing Argus and freeing Io.

Various versions of how Hermes managed to kill his many-eyed adversary float around in ancient literature, but one way or another, Argus was defeated and Io was able to escape - although she was still forced to wander the world for years as a cow, pursued by Hera's biting gad-flies, before Zeus bothered to get around to turning her back into a human woman.

Meanwhile Hera, saddened by the death of her loyal employee with too many eyeballs, supposedly transferred his eyes to the tail of a peacock instead.

Let us return now to Hinduism, and the curious tale of Indra and the Curse of The Thousand Eyeball Vaginas.

This story tells of an unfortunate incident in the life of the famously volatile and lusty Hindu deity Indra, which begins when he seduces (or rapes by means of illusion, depending on the source) the beautiful Ahalya, the wife of the powerful sage Gautama Maharishi. Indra is not particularly stealthy about this, and the enraged Gautama catches him in the act.

While the details of this tale differ across versions and across time, in one common variant, Gautama slaps a curse on Indra that causes him to sprout a mighty crop of a thousand vaginas all over his body:

Since you [Indra] have done such a deceitful and rash action for the sake of a vulva, therefore let the greatest chiliad of vulvas come into being on your limbs! Most wicked one, your penis will fall here. Go from in front of me, fool, to the dwelling of the gods. Heaven-dwellers, tigers among sages, men, and siddhas see together with serpents. (Padmapurāṇa 1.54.29–31)

However, Indra is not saddled with this outbreak of unwanted genitals forever.

In one version, Gautama eventually takes pity on him, and offers to turn all those vaginas into less-embarrassing eyeballs instead. In another version, either Gautama or a sympathetic goddess comes up with the arguably much, much worse solution of leaving the vaginas on Indra, but sticking eyeballs inside of them:

The gods beginning with Brahmā are able to destroy that misfortune born of the sage's curse. I am not, lord of the gods. Nevertheless, I produce an idea today whereby it will not be [lit. is not] observed by people. You will have a thousand eyes in the middles of the vaginas. Known as the thousand-eyed one, you will carry out the rule of the gods. And you will have a ram's scrotum and a penis thanks to my boon. (Padmapurāṇa 1.54.47–50)

One way or another, Indra then becomes Hinduism's thousand-eyed, and also maybe thousand-eyeball-vagina-ed, god. He has gained far broader powers of perception, but he has done it by means of a very strange route.

These ancient stories are weird and bawdy, but they also overlap with far more recent concerns about surveillance and control.

And much like these old stories, current conversations about drones and privacy turn with remarkable and unerring frequency to sexually-tinged fears.

What if that demon machine catches me sunbathing nude in my yard?

What if some faceless and unknowable creep peeks in my window while I'm engaged in certain unspecified sexual activities?

Before drones, people just had to worry about being spied upon by unseen (and easily deniable) spirits while they indulged in certain private and unmentionable acts: today, these little flying robots have translated this ancient anxiety into implacable and all-too-real hardware.

The stories of both Argos Panoptes and Indra also get at the dualistic, blessing-and-a-curse nature of being a being endowed with extraordinary powers of perception, whether that means you're a god, or have merely ordered a drone off the Internet to amuse yourself with.

Despite his god-like powers, Argos ends up being stuck with the scut-work of babysitting a cow that his boss's estranged husband is hot for, and he ends up dying a degrading death as a result. And while Indra survives his own ill-considered sexual escapade, his vaunted status as the 1000-eyed god was originally inflicted on him as a degrading punishment.

While the above stories concern gods and near-gods, there are other old ideas about how less exalted figures can use the spirit world to collect useful and juicy information about the lives of others.

In northern Mongolia, some people believe in “gossip spirits,” (hobooch ongod) mischievous entities that can be used – with a willing shaman’s assistance - to peek in on the affairs of one’s neighbor and family members. Importantly, gossip spirits do not need to appropriate an animal or a human body to move about on their intelligence-collecting missions, a quality that makes them particularly useful.

A person might ask a shaman to use a gossip spirit to check in on how their newly-wed daughter in another household, while a competitive-minded shaman might sneakily whoosh off their shaman spirit to spy on the going-ons of another, rival shaman. The gossip spirit, much like a secret recording device, will then “store everything exactly as it takes place," and relate it or imitate it back to you.

Gossip spirits are not just placid tools, though: they possess their own will and desires. They are entities that find it highly amusing to stir up drama in the human world, and they take considerable pleasure in breaking taboos by means of obscene and absurd behavior.

Perhaps gossip spirits still float among us all, and they've just figured out they can achieve their messy drama-seeking ends on a far grander scale: perhaps they got social media accounts, where they can post endless hot takes about everything from world affairs to condiments to vex doom-scrolling mortals.

For a final example of old spiritual ideas about far-sight and surveillance, we encounter the Norse god Odin and his dual data-collecting remote sensing devices. By which I mean, Odin's intelligent duo of spy-crows.

The one-eyed Odin was regularly accompanied by two ravens named Huginn (“thought or ‘the thinking one’”) and Muninn (“memory or ‘the memorizing one’). Per the Prose Edda, an invaluable 13th century Old Norse work originating in Iceland, Odin would deploy his ravens to monitor the world each morning, collecting information that he required to maintain worldly order. [[3]]

Upon their return, the ravens would sit on his shoulders, speaking about their findings in Odin's ears. Perhaps the two birds can be seen as a sort of spiritual and exponentially cooler precursor to the modern newspaper.

While the birds are technically living creatures, most Norse scholars regard them as embodied symbols for Odin's own memory and mind: much like what we do when we fly a drone today, they are mechanisms for extending his perception beyond its normal reach. Although Odin cannot simply see everything effortlessly, like some other deities in other traditions can, he has cultivated the ravens as organic, goth-coded tools for helping him do so.

Mysteriously, another version of the story has Odin saying this about his duo of avian sensors:

"Hugin and Munin fly every day

Over the vast stretching earth;

I fear for Hugin that he will not come back,

yet I tremble more for Munin.”

No one is entirely clear on why Odin makes this distinction. Perhaps, as the scholar Hermann Pernille theorizes, this passage reflects Odin's fear of forgetting key memories, and of losing his mind. Odin says that he fears for the fate of memory more because he is aware of memory's inherently fragile and ephemeral nature: he is also aware that in the absence of memory, or contextual information, thought isn't good for much.

Meanwhile, in our current age, we are preoccupied with collecting vast amounts of data about people and their affairs with ever-more invasive technological methods, from drones to AI-driven web crawlers. And yet, we very frequently lack context for that data, or a coherent understanding of why we're collecting so much of it in the first place.

At least Odin knew he needed all that raven-collected information to keep the whole ass world from falling apart. We enjoy no similar assurance about the ultimate ends of our technological means.

We've explored more spiritually-rooted dreams about the extension of human perception and sight, in the early stages of the process that would eventually lead to the modern drones that fascinate and frighten us today.

But what about so-called "forgotten technologies" for far-sight and extended perception- more concrete technological concepts and objects that may or may not have actually existed, but which people of the past imagined could have? They will be the topic of the next post in this series.

[[1]] David Lyon has an excellent 2014 paper on this topic entitled "Surveillance and the Eye of God."

[[2]] And if they're on their phones, so is Mark Zuckerberg. But that's a concept for another newsletter post.

[[3]] You should read the Prose Edda sometime, it's a hoot.

Here are the entries in this series so far:

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Preface

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: A Drone of The Mind

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Forgotten Technologies, Towers, and Roman Shitposting

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Death Rays, Brass Horses, and Dragon-Surprising Mirrors

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Pondering Orbs, Black Mirrors, and World-Viewing Cups

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Tower-Jumpers and Hungry Eagles