The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Death Rays, Brass Horses, and Dragon-Surprising Mirrors

There is something creepy about mirrors, an otherworldly and fascinating quality that writers and thinkers have returned to repeatedly throughout the ages.

When I was about four, my grandmother, a scientifically-minded type, took me into their master bathroom and directed my attention to the mirrors on the closet, which reflected the mirrors above the bathroom sink at a slight angle. "When you look into two mirrors opposite from each other, you can see infinity," she explained to me, as I stared with a mixture of awe and existential dread into what seemed like an endless, angular tunnel, leading out from our Tampa bathroom mirror into some unknown, alternate reality.

In that moment, I gained both an abiding discomfort with the concept of infinity (which I spent a lot of time worrying about for the next ten years), and a life-long interest in cosmic horror narratives that involve incomprehensible entities skulking around in mirrors.

add a little existential dread to your life about the meaninglessness of existence next time you're in the bathroom!

Intellectually, most everyone knows, as I did even as a child, that mirrors, and similar reflective surfaces, only really reflect whatever happens to be across from them at the moment. And yet, humanity has also long entertained the suspicion that mirrors, mysterious as they are, are capable of showing us considerably more than just our bleary-eyed and disappointing faces as we brush our teeth.

Humanity has been making mirrors for an extremely long time, as reiterated by the recent discovery of obsidian mirrors dating back to the first half of the 7th millennium BC at the famously ancient site of Çatalhöyük in Turkey. While mirrors have been with us for thousands of years, they were luxury items until very recently - expensive, difficult to make possessions for the elite, the vain, and seekers of the arcane (a Venn diagram that often, and still does, overlap a lot).

Mirrors and other reflective objects are also very arguably the true ideological precursors to television, a technology that eventually begat the data-collection and video-streaming capabilities of the modern drone, as well as many other electronic devices that define our lives today. Thousands of years before the invention of the iPhone, ancient writers slotted mirrors, looking-glasses, and other shiny objects into the place of the omnipresent digital screens of today, imagining what it might be like if these reflective surfaces and optical lenses could show the viewer what was happening many miles away right now. Or in the past. Or in the future.

It is not, I think, a coincidence that so many of the existential fears that mirrors tend to evoke in us are linked to surveillance, to the fear that someone or something is looking at us, unseen, from the other side.

Some part of us seems to recognize mirrors as inherently liminal objects, potentially capable of acting as portals between our own world and other, unknown places. This fear of being seen by certain unknown parties through the mirror also readily connects to common fears for the safety of our souls in the face of evil influence, both in a metaphorical sense (as crops up often in philosophy, from ancient times to today), and in an entirely literal sense.

In a number of Jewish traditions, as just one example among many similar global customs, all the mirrors are carefully covered within a house where someone has recently died. While there are a number of different explanations for this practice, some sources claim that this is done because evil spirits are attracted to mirrors, and the occupants of a house in mourning are particularly vulnerable to their influence.

Russian folk catoptromancy by Karl Briullov in 1836, an early 20th century Halloween card, and Mary 1st the England.

Meanwhile, adolescents at sleepovers around the globe still congregate around mirrors in the dead of night and attempt to commune with the sinister presence of Bloody Mary, re-enacting a school kid ritual that likely dates back at least to certain future husband-viewing rites of the 1800s, and may even be a half-remembered reference to the religiously-driven ferocity of Mary I of England herself. While the relative details of what Bloody Mary actually does to you once you've summoned her vary enormously (screaming at you, scratches on the side of the face, straight-up sudden death) all variants on the story agree that she requires both a mirror and the explicit complicity of the summoner to make an appearance in your bathroom.

While many cultures view mirrors as potentially dangerous, they are also often viewed as potent supernatural tools in the hands of the right person. The Chinese Taoist tradition, for example, holds that magic mirrors can be used to reveal the true shape of demons, while the related tradition of Feng Shui teaches that mirrors can be used to reflect the bad energy of demons and other malignant forces - but can also cause serious problems when placed in the wrong location, such as facing the bed.

In addition to these older, more consistently established traditions, we are constantly, chronically coming up with new stories, movies, and Reddit creepypasta posts that feature Mirrors Grown Wrong: sucking people into upsetting alternate dimensions, providing a convenient transport mechanism for unwanted ghosts and spirits, and subtly distorting our images in ways that drive us into gibbering madness, among a variety of other unpleasant powers.

Inevitably, these well-worn cultural ideas about mirrors seep into our own perceptions. Most all of us have gotten up to use the bathroom at 2:00 AM in a dark and silent house, and found ourselves fearing, just a little bit, the prospect of seeing something unexpected looming behind our reflections in the mirror over the sink. Indeed, I struggle to think of any other commonplace bathroom appliance imbued with more mythological and often ominous meaning. No one has been crafting myths for thousands of years about the occult uses of toothbrushes or sponges.

an ancient Scythian mirror from the 7th century BC, Neolithic mirrors from Çatalhöyük, a Han Dynasty bronze mirror.

Some imagined antecedents to today's televisions, satellites, and drones - "vanished technologies," to use an extremely useful term fleshed out in the work of researcher Benjamin B. Olshin - can be traced back to a corpus of folktales whose essential themes may be of great antiquity.

The Aarne-Thompson-Uther index is a fascinating attempt to classify the narrative elements of folktales from around the globe, first devised in the early 1900s as a means by which folklorists might identify and categorize the common themes running through the stories that we've been telling each other for a very long time. While it is pretty much impossible to determine exactly how old these folktales are, there is compelling phylogenetic evidence that at least some of these stories can be traced all the way back to the Bronze Age.

One such recurring story type is known as the “Rarest Thing In the World,” a "dilemma" tale whose general form has been observed among both Indo-European cultures and among the cultures of Western Africa. The story begins with a princess, whose hand in marriage is offered to anyone who can bring her the rarest thing in the world. A set of three brothers decide to compete for this prize, and each presents her with a rare and powerful object. One brother produces a flying carpet "which transports one at will." Another attempts to impress her with an apple (or a similar object) that can heal the ill or bring back to life the dead. The last brother, not to be outdone, breaks out a "telescope" (or a similar reflective device) that can show "all that is happening in the world."

With this remarkable telescope, the brothers learn that the princess is either dying or is already dead. They use the carpet to rush to her side, and use the fruit to restore her to life. An argument than, inevitably, ensues over who will actually get to marry her. Versions of this ur-story form, complete with the aforementioned clairvoyant telescope, emerge in a number of very familiar places, including in compilations like "Grimm's Fairy Tales" and the "One Thousand and One Nights," often also referred to as the "Arabian Nights."

Here is how the Grimms describe this far-seeing device in "The Four Skiful Brothers," an item which one of the brothers obtains after he enters the service of a passing astronomer (academia sure was different back then):

The second brother met a man who put the same question to him what he wanted to learn in the world. “I don’t know yet,” he replied.

“Then come with me, and be an astronomer; there is nothing better than that, for nothing is hid from you.” He liked the idea, and became such a skillful astronomer that when he had learnt everything, and was about to travel onwards, his master gave him a telescope and said to him, “With that you canst thou see whatsoever takes place either on earth or in heaven, and nothing can remain concealed from thee.”

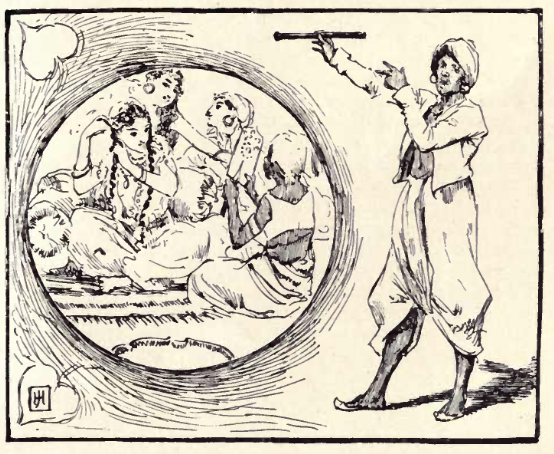

Yet another tale of this type appears in the "Thousand and One Nights," when a princely character pauses at the marketplace in the Persian kingdom of Shiraz, arrested by the sight of a crier (a sort of olden-days sales representative) attempting to sell a mundane-looking "ivory tube about a foot in length and about an inch thick" for a startlingly high price.

The crier presents the ivory tube to the prince, telling him that "this tube is furnished with a glass at both ends; by looking through one of them you see whatever object you wish to behold." The prince is deeply skeptical, but he takes him up on it:

'I am,' said the prince, 'ready to make you all proper reparation for the scandal I have thrown on you, if you will make the truth of what you say appear'; and as he had the ivory tube in his hand, he said, 'Show me at which of these ends I must look.' The crier showed him, and he looked through, wishing at the same time to see the sultan, his father. He immediately beheld him in perfect health, sitting on his throne, in the midst of his council. Afterwards, as there was nothing in the world so dear to him, after the sultan, as the Princess Nouronnihar, he wished to see her, and saw her laughing, and in a pleasant humour, with her women about her.

Naturally, Prince Ali buys the thing, and the story proceeds along fairly familiar lines from there.

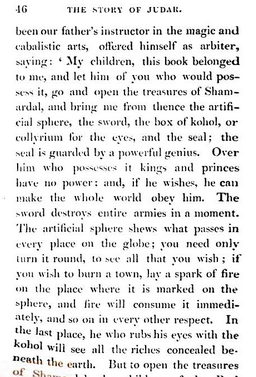

In the mysterious and bleak "Story of Judar," another tale from the lengthy, many-versioned, and deeply confusing corpus of the "Thousand and One Nights," a similar far-seeing device pops up, accompanied by a high-tech pot of eye makeup:

Unlike the vast majority of other far-seeing devices in old literature, the "magical sphere" in the "Story of Judar" gives the user much more than just an enhanced view of the globe: it gives them the ability to remotely commit mass murder. I can think of no more stark example of how people were imagining the possibilities of drone warfare many, many years before such a thing ever became possible.

Another compelling antique story that concerns technologically-advanced mirrors comes to us from the Gesta Romanorum, a compilation of Latin stories and vignettes that appears to date from around the end of the 13th century. While it does contain a number of tales concerning the supposed deeds of the ancient Romans, it also includes early versions of a remarkable number of other well-known stories in the European and Asian literary tradition: latter authors of the past, from Shakespeare to Chaucer, likely used these tales for both source material and inspiration.

Although the Gesta was probably initially compiled as a sort of moral and religious manual for priests by a member of the clergy, likely somewhere in England or Southern Germany, translations of the book became wildly popular amongst the general public for generations. And it does contain some Weird Mirror Stuff.

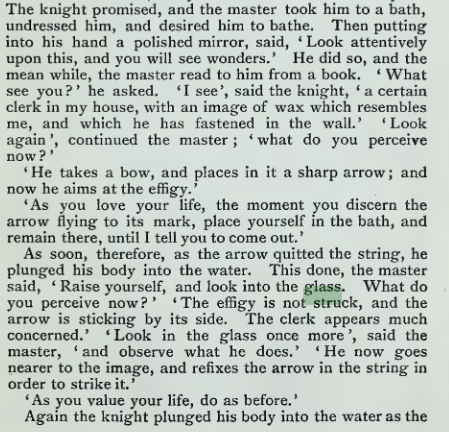

In one tale, rather loftily titled "Of the Transgressions and Wounds of the Soul," a Roman knight in the time of Titus is cursed with a beautiful but chronically unfaithful wife. To deal with his sorrow, he decides, a smidgen anachronistically, to take a trip to the Holy Land. Upon his departure from Rome, his wife immediately takes up with an alluring local necromancer. The wife tells the scofflaw that she will marry him if he manages to get her husband out of the way, and he duly prepares to use his dark arts to kill the knight from a safe distance.

Meanwhile, the knight encounters a wise man upon the road who tells him that he knows that his harlot wife is plotting his imminent death. The knight will only be saved if he does exactly as the wise man says. The knight dutifully obeys the directive of the stranger, who takes him to a public bathhouse and helps him to undress. (This story would have rather different connotations if it was written today). He gets into the bath, the wise man hands him a mirror, and this is what happens next:

Like the rest of the stories in the Gesta, this one ends with the sort of preachy Christian moral message that was expected of writers and compilers of the era: we are informed at the end that the "bath is confession; the glass, the Sacred Writings, which ward off the arrows of sin."

I guess, but it's the cartoonish complexity of the narrative's mirror-powered double-cross that makes this story really interesting. What we have here is, I'd argue, not just a medieval conception of remote warfare (as we saw in the "One Thousand and One Nights") but of remote counter-warfare as well.

some portrayals of the Squire's Tale. it's rather surprising that there aren't that many illustrations of this one, what with the robotic horse, magical mirror, the talking falcon, and the Golden Horde to work with.

I mentioned flying horses in the last part of this series, a sort of Chekhov's Equine, and I intend to make good on that promise. I do so with the assistance of the aforementioned Geoffrey Chaucer, who in his unfinished "The Squire's Tale" describes what happens when a heroic Tartar king has his birthday party crashed by a singularly freaky, mysterious knight, who rides into the hall upon a horse made of brass, carrying a "brood mirour of glas" in his hand.

In the Middle Ages, in that low-stimuli era before the Internet, having a mysterious stranger with odd toys barge into your party uninvited was free entertainment. This was even true in Saray (Sarai), the mighty capital of the Mongols of the Golden Horde, where we are told that this story takes place. As such, the king and his guests eagerly listen as the knight explains that his liege-lord, the King of Araby and Ind, has decided to honor him with a series of gifts - among them, the horse:

Notably, Chaucer's brass horse explicitly ships with certain autonomous functions - above and beyond the self-driving capabilities of a bog-standard, biological horse, anyway:

The knight then turns to a description of the mirror:

While no one in the Tartar king's court is quite clear on how it works, it's assumed by the crowd that it's got something to do with human engineering, much more so than magic:

Unfortunately, we never hear more about what the King and his daughter ultimately end up doing with the brass horse and the mirror, because, in Chaucer's framing, the poor Squire is rather rudely interrupted by the Franklin, who proceeds to tell his own, considerably more boring story. Still, the fragment we have is plenty interesting enough .

If we assume that the horse's rider would be able to consult the mirror while cantering thousands of feet in the air, then we must conclude that Geoffrey Chaucer managed to imagine us most of the way to a modern drone by the late 1300s. Or at least, most of the way to a modern aerial intelligence-gathering operation. (Can you imagine a medieval knight on a flying horse armed with that remote-murder sphere from the "Thousand and One Nights?" Because I can, and I would absolutely watch that stupid movie).

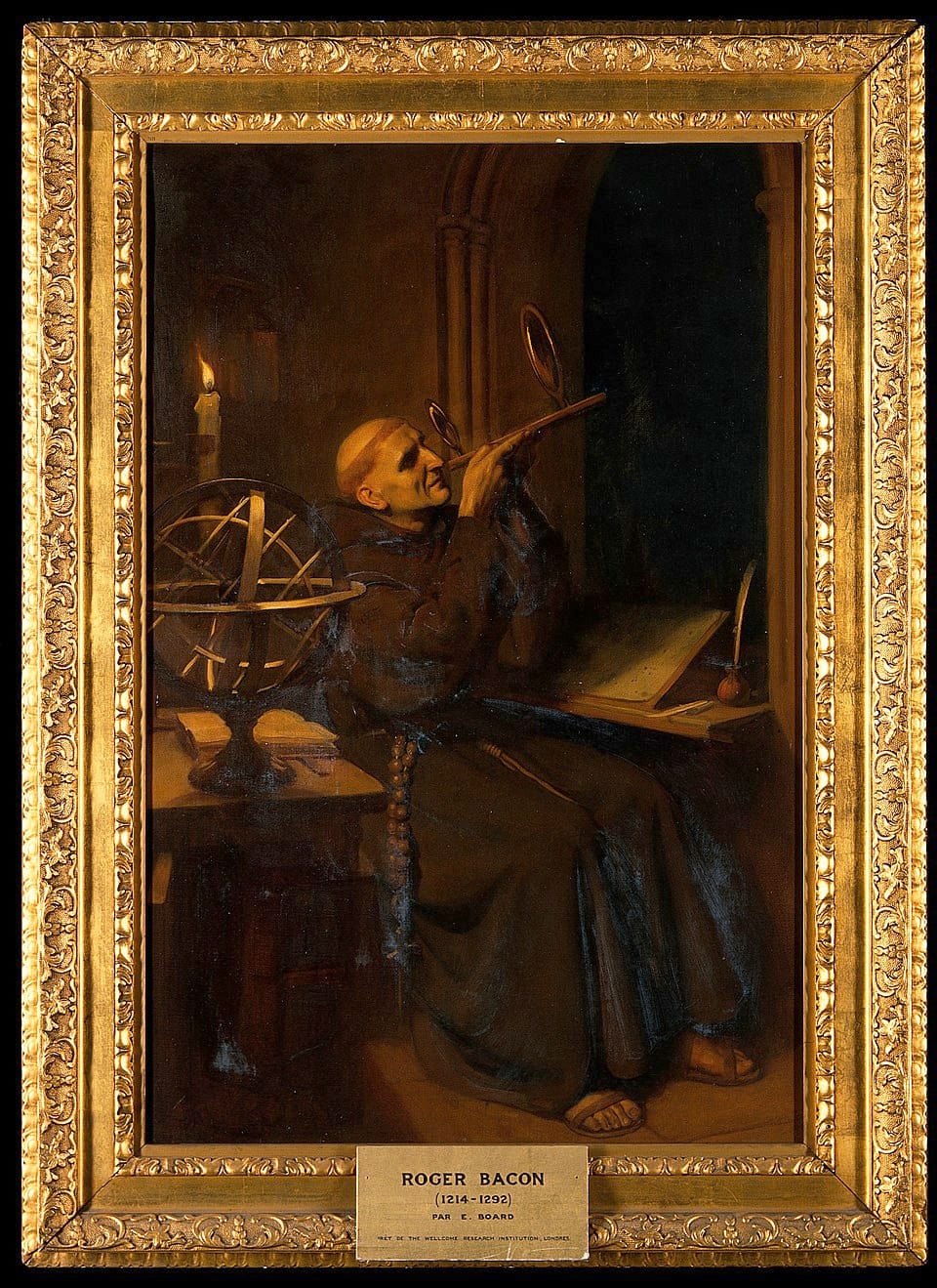

various historical portrayals of Roger Bacon doing his thing

As in inevitable in pretty much any work discussing medieval technology, we now arrive at the 13th century philosopher, polymath, alchemist, and Franciscan monk Roger Bacon, who played a key role in the intellectual tradition that would eventually result in modern science. In about 1267, Bacon compiled a speculative document on natural phenomena and how these might be harnessed to create future technologies, known rather awkwardly as "The Letter Of Roger Bacon Concerning The Marvelous Power Of Art And Nature And The Nullity Of Magic."

Dire as the title may be, it's still startlingly compelling reading today, a medieval voice from the distant past wildly imagining, often fairly accurately, where human ingenuity might take us in the future. With an emphasis on "fairly": within the text, Bacon combines prescient predictions about the future existence of technologies like scuba diving, flying machines, and motorized vehicles with straight-faced declarations that basilisks can "kill by sight alone" and that there are women in Scythia who have "twin pupils in the eye and who when they are angry kill men by a glance."

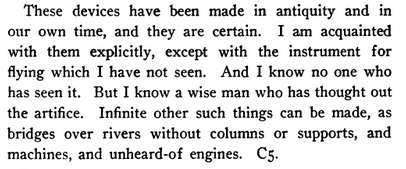

Notably, Bacon did not believe these human-created "natural marvels" that he wrote about to be related to magic. Indeed, he emphatically states that in "these there is no magic whatsoever, because, as has been said, all magical power is inferior to these works and incompetent to accomplish them." Nor did he believe that these devices were inherently tools of the future, but instead, tools that the lesser minds of his own society merely failed to appreciate at the time - he even claims, a little suspiciously, that he's seen most of them himself, except for the flying machine:

As for why such devices are not currently in widespread use, Bacon has a ready explanation for that too. The common man simply can't be trusted to handle the truth:

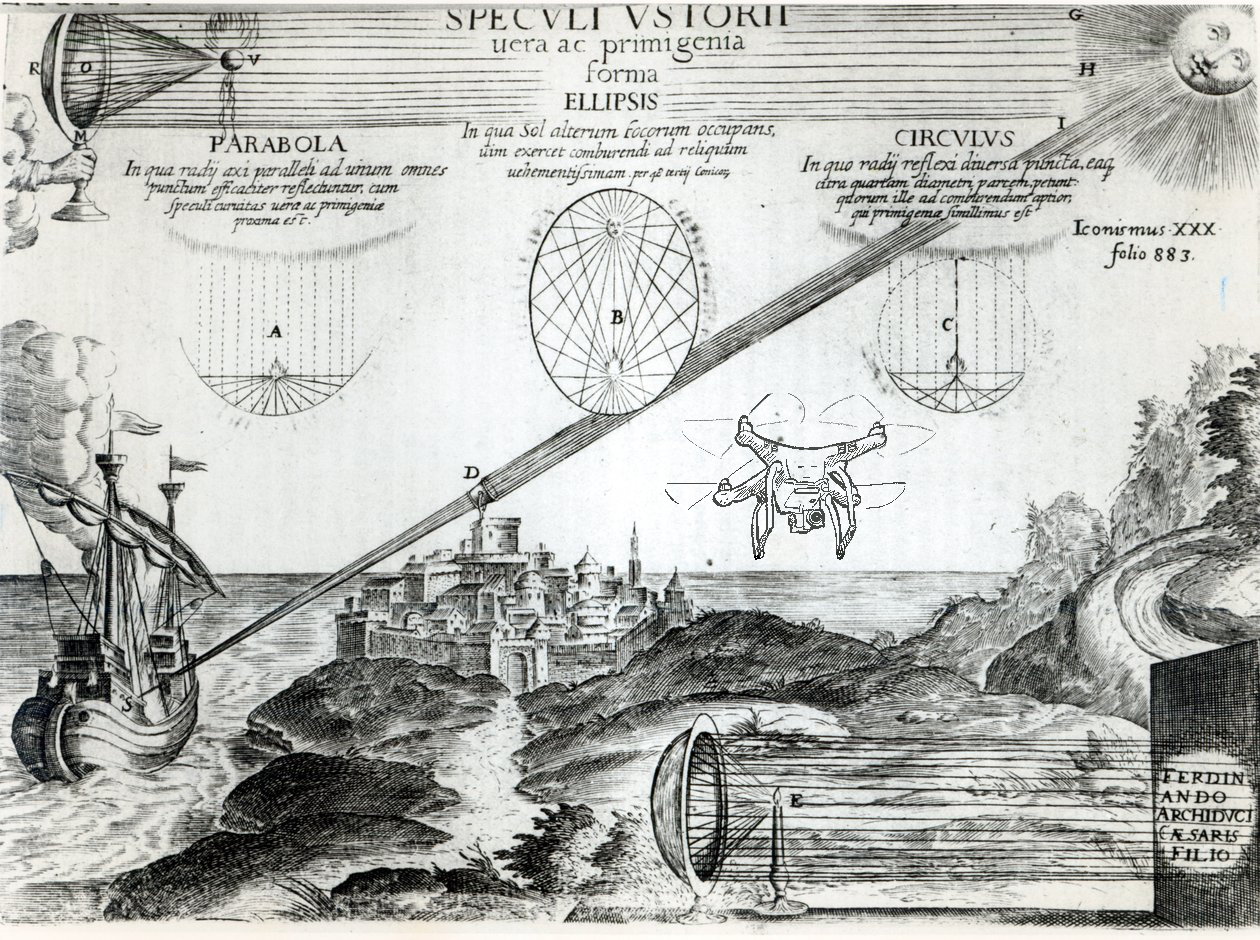

A number of the hypothetical inventions that Bacon describes in the "Letter" exist within the realm of optics- what we now define as the science of harnessing the genesis and propagation of light, via mirrors, glass lenses, and other contrivances. In the text, Bacon reflects (hah) upon how "mirrors and perspective devices can be so arranged" as to produce startling illusions, which can be used to cast "infinite terror...upon a whole city or upon an army so that it will go entirely to pieces because for the apparent multitude of the stars or men congregated about it."

Beyond illusions, Bacon also considers the surveillance possibilities of optical devices, which permit humanity to "read the smallest letters at an incredible distance." Bacon his account, Julius Caesar himself used these reflective methods to cleverly scope out the locations of the English camps and cities in advance of his invasion from the shores of Gaul - though if Caesar actually did this, he didn't bother to mention it in his own memoirs. So too, Bacon claims, did Socrates and Alexander the Great make use of mirrors for intelligence-gathering purposes:

Interestingly, the dragon-mirror-Socrates story may come from Roger Bacon's own 1200s contemporary, the German Dominican friar and philosopher Albertus Magnus, who used it to illustrate the means by which air becomes corrupted:

Beyond these feats of using optics to identify and bamboozle mythological reptiles, Bacon's "Letter" also considers the possibilities of using a mirror for purposes of burning anything that it is turned upon, like an antique death ray:

Bacon's notions of a weaponized battle-mirror did not come from nowhere. He was participating in a lengthy tradition, likely first launched into European and Asian awareness by Archimedes' infamous mirror-powered "death ray" which he legendarily used to fry the Roman fleet as it descended upon Syracuse in 212 B.C.

Constant debate has raged on ever since about if these mirrors could have actually existed, or if they're a mere historical embellishment, and I lack both the space and the emotional energy to wade into it here. But hey, a 13 year old Canadian kid built a working model of Archimedes death ray in 2024, so the dream continues to live on.

Experiments into burning mirrors would continue throughout the Middle Ages. The Persian mathematician Ibn Sahl, in the year 984, wrote an optical treatise expanding upon Ptolemy's own, largely lost, 2nd century work. Within the partially-surviving treatise, Sahl explores the interesting possibilities of crafting mirrors that could be used to start fires at a distance. This subject was taken up further by his contemporary, the considerably more famous scientist Ibn al-Haytham of Baghdad, whose work, in turn, was very influential for Roger Bacon, as well as for the eventual development of the scientific method itself.

Across the ocean, the people of the Americas also discovered the connection between mirrors and convenient at-a-distance fire starting. According to the half-Inca scholar Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, who wrote in the 1500s, Inca priests once used reflective bracelets to start ceremonial flames for sacrificial purposes:

And ah, here's Roger Bacon. Again. After the great philosopher's passing, his works swiftly passed into the realm of legend and speculation: he became something of a folk hero to the nerds of the Middle Ages. By 1385, the Franciscan writer Peter of Trau penned one such work of fan-fiction, in which he claimed that Bacon had constructed two different magical mirrors at Oxford University:

This account is particularly intriguing because it describes a sort of medieval version of modern day video calling technologies - and then manages to extrapolate out from there about what the social consequences of such a tool might be if it was placed in the hands of distractable college students. Still, the Oxford students here merely use the mirror for the sympathetic purpose of checking in on their loved ones. Imagine what would have happened if Bacon had put some games on that thing, too.

In 1608, a humble German-Dutch glasses maker named Hans Lipperhey invented the first refracting telescope, ushering in an era of scientifically-minded, non-supernatural looking at stuff from really far away that continues to this day. Or maybe it wasn't Lipperhey who invented the telescope, and it was in fact some other optically-minded specimen kicking around in the same era - the main point is that humanity had finally created a tangible mechanism (often based on mirrors) for the distant observation of everything from troop movements to the heavens themselves, and nothing would ever quite be the same.

Interestingly, fascinating as telescopes were at the time, and still are today, there is precious little historical literature out there attributing them with the sort of supernatural communication abilities that we still sometimes associate with mirrors today. Nor do telescopes feature frequently today as props in horror movies or within the creepy folklore of the modern Internet: powerful as they are, we simply don't seem to find them as inherently spooky as we still find mirrors to be today.

Perhaps that's because the introduction of the telescope coincided neatly with the blooming of the European Scientific Revolution, and the thinkers of that new age of cultural devotion to logic, reason, and observable experiments had far less appetite for coming up with dubious-sounding stories about telescopes capable of surveillance continents away. Telescopes were no longer an imagined technology: the real thing had finally caught up with that old fantasy of being able to view things that were happening very far away.

The stories about all-seeing mirrors and powerfully effective glass tubes that I've shared thus far all concern forgotten or imagined technologies, in the Benjamin Olshin sense: they share a certain pragmatic, prosaic quality. They do not seem to require a great deal of special technical or spiritual skill from the user. The hard part is acquiring these potent tools for long-range surveillance and communication. Once a person has one of these objects, though, they can make use of it without much of a learning curve. Curious-sounding and unusual as they are, they're essentially equivalent to pre-modern smartphones.

The next entry in the "Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone" will concern a related, yet even more eccentric group of objects that people once believed could be used to see things very far away. These are overtly magical items, those that are used only by certain specialists with a very specific set of skills, and only under unique and unusual conditions. Some call the art of using these objects scrying, some call it captromancy, and some relate it all back to, well, pondering an orb. No matter the term of art, and no matter how weird they may sound, these occult practices also played a pivotal role in helping us imagine our way into the technologies that would eventually lead to both modern drones and the modern world itself.

Here are the entries in this series so far:

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Preface

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: A Drone of The Mind

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Forgotten Technologies, Towers, and Roman Shitposting

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Death Rays, Brass Horses, and Dragon-Surprising Mirrors

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Pondering Orbs, Black Mirrors, and World-Viewing Cups

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Tower-Jumpers and Hungry Eagles