The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Forgotten Technologies, Towers, and Roman Shitposting

Humanity has long dreamed of being able to see everything around us. From the perspective of a bird. From the perspective of a god. From the perspective of a vast network of god-like eyes.

Today, we have constructed tools, like drones and satellites and airplanes, that allow us to do all of these things. To do so, however, our species first needed to learn how to bridge the gap between mythological imagination, and tangible invention. Luckily for us, we have been doing that for a very long time.

This series has so far dealt with old human ideas about the projection of the spirit over distances by supernatural means, in ways that bear a resemblance to the drone technologies of today.

Now, we will be considering ancient drone-like ideas of a somewhat different nature, which fall into the category of what the historian Benjamin Olshin defines as "lost" or "vanished" technologies in his 2019 book "Lost Knowledge: The Concept of Vanished Technologies and Other Human Histories."

According to Olshin, there's a key difference between ancient tales that appear to speak of so-called allegorical technologies - mechanisms and ideas that exist in the realm of spirit and myth - and ancient ideas about more realistic-seeming tools that could have conceivably existed at some point, but have now faded into the uncertain mists of time.

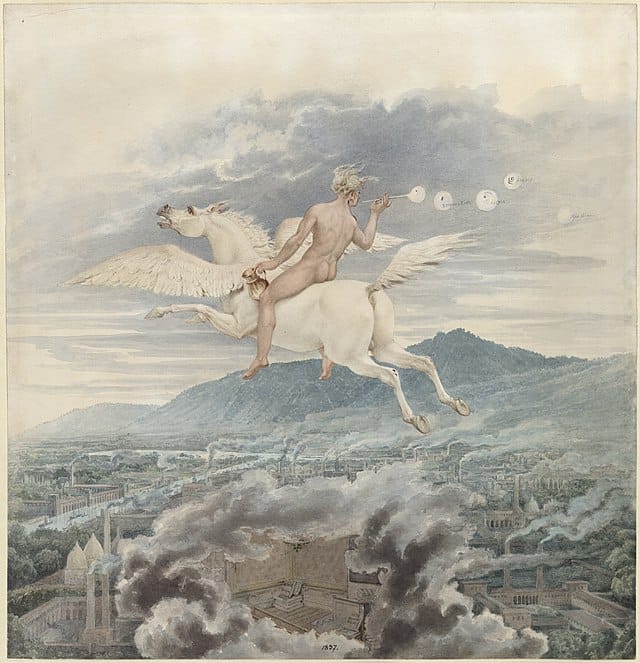

pegasi (?) from pompeii, 2nd to 3rd century AD France, and an 1837 painting by Christian Peter Wilhelm Beuth

To put this in more concrete terms, let us imagine two different passages from writers of the past, both of whom are describing a flying horse.

The first writer describes something like Pegasus from ancient Greek mythology - a beast sired by the god Poseidon and foaled by the Gorgon Medusa, and who has wings simply because that's the way he is.

While Greek mythology does explain where Pegasus comes from, it does not linger long over the nitty-gritty of how a nautical god and a Gorgon can get it on and end up with flying equine offspring, much less the logistics of how a flying horse gets into the air.

Which is fine, even if I can readily imagine some frustrated, sweaty critic with a YouTube channel sharpening their takes on the narrative inadequacies of classical literature. Explaining the technical details isn't the point of mythology, nor does it need be.

The second writer, meanwhile, describes a flying horse in considerably more mechanical terms, attributing it to a certain engineer, or an eccentric genius, or maybe a particularly crafty wizard.

While the writer may not linger long over the technical details - after all, in most historical examples of works like these, they're describing tools that we're pretty sure never actually existed - they provide enough such information that we can readily imagine the possibility of such a mechanism being constructed by mortal means.

In the hands of the second writer, the flying horse is thus depicted as an artificial object, an incredible mechanism that owes its existence not to nature or to divine intervention, but to human ingenuity. While we can be pretty sure that neither of these two flying horses are, or were, ever actually real, it is also clear that the writers who describe them are doing rather different things.

One is operating in the realm of pure myth, where how something works is not of particular importance to the broader story. Meanwhile, the other is considering, at least theoretically, how such a thing as a man-made flying horse could actually work.

Importantly, it's easy to find examples of both styles within the same cultural tradition, and sometimes, even within the same story.

Returning to ancient Greece, consider the weird and violent adventures of the Athenian hero Theseus. In most versions of the Cretan interlude of the narrative, the half-bull, half-human Minotaur is described as a fairly straight-forward magical creature. We are usually told that the Minotaur's horrible, degrading existence is the result of the gods deciding to punish King Minos for being way too proud of his prize bull. (The status symbols of the rich were different back then: presumably, if the story happened today, King Minos would be punished by the gods for being far too impressed with his custom Bugatti).

In contrast to the Minotaur, the labyrinth that the engineer Daedalus is said to have constructed to contain both the Minotaur and the unfortunate youths that the monster feeds upon is usually depicted as a distinctly non-magical work of human cleverness. It is easy to imagine that such a place could have actually existed, and indeed, archaeologists have been looking for labyrinths on Crete for generations - though nothing has turned up so far.

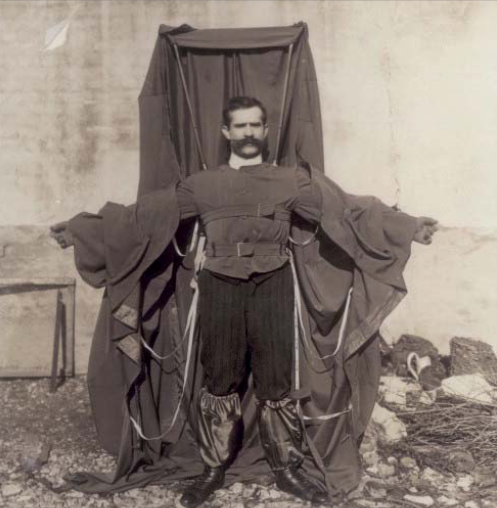

The wings that Daedalus is said to have cobbled together while trapped in King Minos tower are described as similarly non-magical items. While we know now that constructing artificial wings and sticking them on your arms would ultimately prove to be a poor path genuinely controllable human flight, I'd argue that to an ancient observer, Daedalus's wings likely would have sounded a lot more plausible than a guy with the head of a bull.

the tragically optimistic Franz Reichelt, Jacob Peter Gowy's 1600s "The Fall of Icarus," and a Pompeii mosaic of the Minotaur.

Indeed, the artificial wings idea proved to be so sticky that as late as 1912, a French tailor named Franz Reichelt would insist on testing his home-made wingsuit by leaping off the top of the Eiffel Tower, whereupon he plummeted to his death. And just as was the case for poor Franz a few thousand years later, these artificial wings prove to be the death of Daedalus's son Icarus, who ignores his father's instructions and flies too close to the sun, melting the wax that holds them together. (But maybe both Reichelt and Greek mythology have been vindicated, considering that we do have wingsuits today, even if they lack vertical take-off capacity and are incredibly likely to kill you).

Here's another way to think about the distinction between mythology and forgotten technologies: it's a lot like the arbitrary, yet very real choices we constantly make about which works of fiction get shelved with fantasy, and which get shelved with science fiction.

While two different books may both feature uncomfortably attractive five-eyed alien wolf people, the one that also digs into the nitty-gritty technical details of how those sexy five-eyed-alien-wolf-people construct their inter-dimensional caribou hunting warships is probably going to get stuck in the sci-fi section, all other factors being equal.

But I digress, which is tempting to do when sexy five-eyed alien wolf-people come up.

The point is that human history contains both mythological and more realistically-grounded explorations and examples of the concepts and technologies that would, eventually, lead to the creation of the modern drone.

What was the first demonstrably real human surveillance technology, the first verifiable stab our species made at using tools to more effectively creep on what others are doing - for the purpose of both curiosity and control?

I believe the answer is "really tall buildings."

Many of the world's oldest surviving monumental structures are towers, pyramids, and other similarly elevated attempts at artificially replicating a high-up view. Over 11,000 years ago, Neolithic people built the tower of Jericho in Palestine's West Bank, a 27-foot-tall building that must have been genuinely astonishing to behold for a society only just beginning to transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture. Older still are the five round towers of Tell Qaramel in Syria, which may have been constructed as many as 12,600 years ago - evidence that humans have been focused on artificially replicating the view from above for an astonishingly long time.

Although it's impossible to say for sure what motivated these ancient architects, we can, I think, make a pretty educated guess about one key rationale. Let me quote the god-emperor of surveillance studies himself:

"The idea of the panopticon is a modern idea in one sense, but we can also say that it is completely archaic, since the panoptic mechanism basically involves putting someone in the center – an eye, a gaze, a principle of surveillance – who will be able to make its sovereignty function over all the individuals [placed] within this machine of power. To that extent we can say that the panopticon is the oldest dream of the oldest sovereign". - Foucault, Michel, Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977–1978 [2004]. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

To an ancient ruler or religious leader, a tower or a pyramid that commanded an expansive view was more than a structure. It was a tool, a mechanism at least in part intended to ensure that their splendor could be seen from a great distance, permitting them to both impress and intimidate both their supporters and their enemies.

At the same time, these towers granted them a privileged view of both their immediate surroundings as well as the heavens - and indeed, many pre-modern towers and pyramids appear to have been intentionally aligned with the solstice and with other key celestial events. While these buildings were crafted by human hands, a number of cultures appear to have viewed them as microcosms of creation itself, imbued with deep symbolism:

"The pyramid is an image of the world; in turn, that image of the world is a projection of human society. If it is true that man invents gods in his own image, it is also true that he sees his own image in the images that the sky and the earth offer him. Man makes human history of the inhuman landscape; nature turns history into cosmogony, the dance of the stars."

Octavio Paz, The Other Mexico, p. 294

Angkor Wat in Cambodia, thought to represent the sacred Buddhist center of the world of Mount Meru, and the Mayan Temple of the Magician at Uxmal.

What's more, these elevated buildings were often designed in such a way that someone residing or working at the top could choose whether or not they wanted to be seen by those below. It's a recipe for generating considerable psychological uncertainty among the populace about if they're being watched - either by powerful humans, or by supernatural forces mediated by powerful mortals - at any given time. To very gently paraphrase Foucault: voila, that's how you get a sick panopticon.

By controlling access to these structures, leaders could also grant access to a kind of early visual super-power to those deemed worthy of it. If we consider how excited many still get today by the prospect of climbing to the top of a tower or a pyramid - to such an extent that the long-suffering caretakers of modern archeological sites must constantly chase feral influencers away from lofty restricted areas - imagine how thrilling it might have been to get access to these sweeping views in a time before photography or the printing press.

And I mean, I get it.

I may find myself eye-rolling at how many of my fellow tourists seem to possess the same insatiable, instinctual desire to climb to the top of stuff that you see demonstrated by confused ladybugs, but I've also spent many happy moments of my own at the top of Mayan pyramids and Khmer temple mountains - watching weather roll in from far away, taking a bit of voyeuristic delight in observing people from far below who seem totally unaware that I've noticed them. (It's true that most of the time no one is judgmentally watching you in public, but it is haunting to consider that this is never true all of the time).

It's also easy to deduce where our ancestors got their ideas about building really tall structures as mechanisms of both control and symbolism. After all, many global religious traditions imagine the gods occupying a seat in the sky that permits them a privileged perspective over the affairs of mortals on the ground. Today, we even regularly live out this idea by means of the elevated map perspective of many modern real time strategy and simulation computer games: we must imagine Zeus playing a lot of Age of Empires.

Numerous examples of what could arguably be called ancient surveillance structures exist in history.

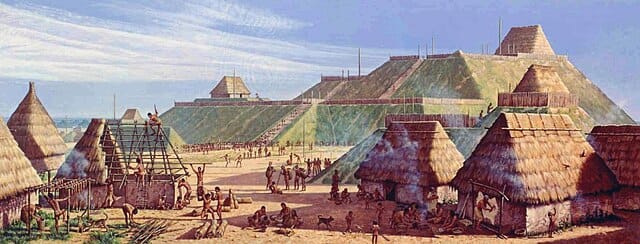

One of my favorite such theories concerns the monumental burial mounds of the medieval city of Cahokia in modern-day Illinois, which was, around the year 1100, home to as many as 40,000 people and sprawled across six square miles. If the upper estimate is correct, that would mean that Cahokia was the largest city ever constructed in the United States until the 1780s, when Philadelphia finally surpassed it.

The people of this remarkable Native American civilization were keen on constructing monumental earthwork mounds, and they made well over a hundred of them. We know for sure that they were used for burials, and quite plausibly for other ceremonial and spiritual purposes.

The largest such earthwork structure, the Monks Mound, was over 100 feet high and had a structure built on top of it that may have functioned as a temple or a residence for Cahokia's leadership, perhaps as a sort of pre-modern penthouse suite. According to a recent study incorporating geospatial analysis techniques, people moving about on top of the mound outside of this high-status structure would have been visible from about 83.4% of the land within four kilometers of the structure.

While the people of Cahokia left behind no written records, I find it pretty plausible that the average non-elite resident would have responded to that constant visual reminder of structural power with some combination of irritation, paranoia, and uneasy resignation - responses that closely resemble how many people today respond to the meant-to-be-seen presence of obvious surveillance cameras, intrusive corporate employee monitoring software, and, of course, drones.

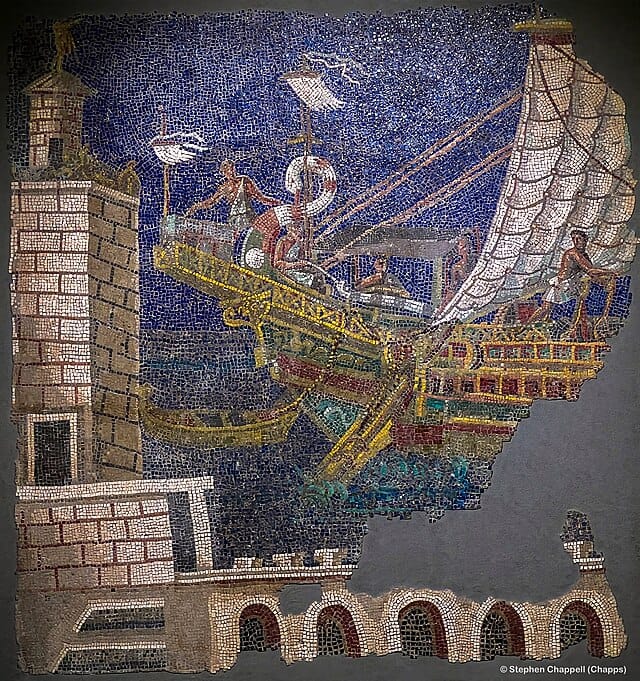

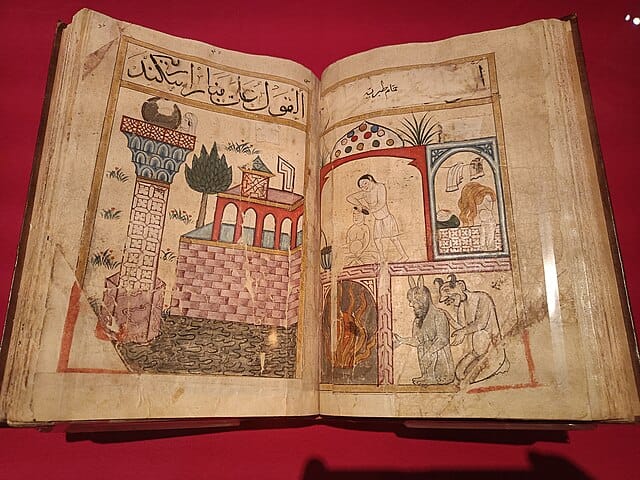

a modern reconstruction of the Pharos, a splendid ancient Roman mosaic depicting the Pharos, and a drawing of it by Abd al-Hasan ibn Ahmad al-Isfahani in his Katab al-Bulhan (Book of Surprises), Iraq or Iran, 14th century.

Even further back in history, we encounter the enormous Pharos (Lighthouse) of Alexandria, which the ruler Ptolemy Soter had constructed around 290 B.C. Experts estimate that this gargantuan Ancient Wonder of the World reached a height of 330 feet, making it one of the world's tallest man-made structures for many generations: indeed, it managed to survive for 1600 years, before eventually collapsing into the ocean. (As of July 2025, archeologists have begun to pull up some of the monument's long-submerged stone blocks from the sea).

The Pharos performed its core lighting function by means of a beacon chamber at the top of the tower, which had space both for an enormous fire at night - at least, when scarce ancient Egyptian wood supplies would permit - and a gigantic, burnished bronze mirror, which could reflect the sun with such fierce intensity that it could be viewed during the day time, aiding ships entering the harbor.

Useful as the Pharos was as a lighthouse, it also must have been extremely handy as a surveillance mechanism, a means by which someone could readily observe ships coming and going into Alexandria's busy harbor from a very great distance - even though it seems very unlikely, despite certain claims, that you could see Rome and Constantinople from the top if you squinted hard enough.

Arguably most importantly of all, the Pharos was meant to be seen, emphasizing the glory and power of the civilization that had constructed it. According to the first century Roman-Jewish historian Josephus, the flame could be observed at night from as many as 300 furlongs (34 miles) away - which is not quite all the way to Rome, but is still plenty impressive, especially by the standards of the classical era.

Nor was the Pharos viewed with awe and appreciation just by mariners. For many generations, the monumental lighthouse served one of the ancient world's premier tourist destinations, a building that became as synonymous in popular culture with Alexandria as the Eiffel Tower is of Paris today. Imperial Roman era travelers to the Pharos were able to purchase souvenirs with depictions of the tower etched into them, from glass vessels to jewelry: one such object would eventually turn up as far away as Afghanistan.

In another testament to its visibility, the Roman-era satirist Lucian referenced the Pharos in his satirical work Icaromenippus ("The Sky Man"), in which a cynic philosopher attempts to ascend into Heaven and Zeus's citadel by means of wings pilfered from an eagle and a vulture - and ah, there's those artificial wings again.

Menippus, the protagonist, has better luck with his wings than Icarus or swiftly ascends to such a great altitude that he is only able to re-identify the Earth by catching a far-off glimpse of familiar, man-made monuments:

"If I had not caught sight of the Colossus of Rhodes and the Pharus tower, I assure you I should never have made out the Earth at all. But their height and projection, with the faint shimmer of Ocean in the sun, showed me it must be the Earth I was looking at. Then, when once I had got my sight properly focused, the whole human race was clear to me, not merely in the shape of nations and cities, but the individuals, sailing, fighting, ploughing, going to law; the women, the beasts, and in short every breed 'that feedeth on earth's foison."

Nor was "Icaromenippus" the only work in which Lucian took on the topic of viewing the world from a drone-like, or satellite-like, perspective. Even weirder themes emerge in his "True Story," a bizarro fake travelogue highly reminiscent of Jonathan Swift's"Gulliver's Travels," concerning a metaphor-laden ship journey that crosses both earthly oceans and the cosmos.

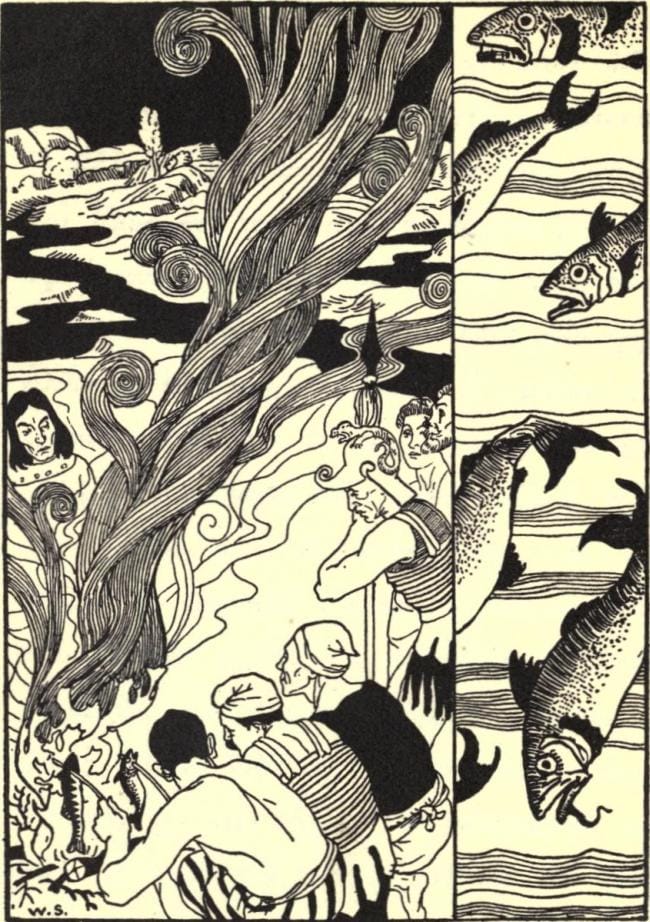

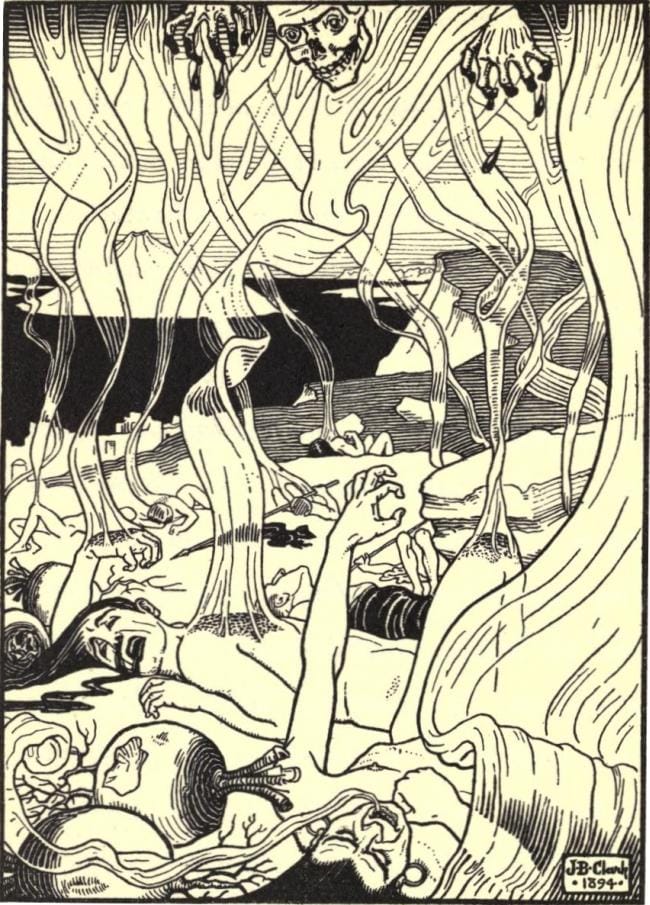

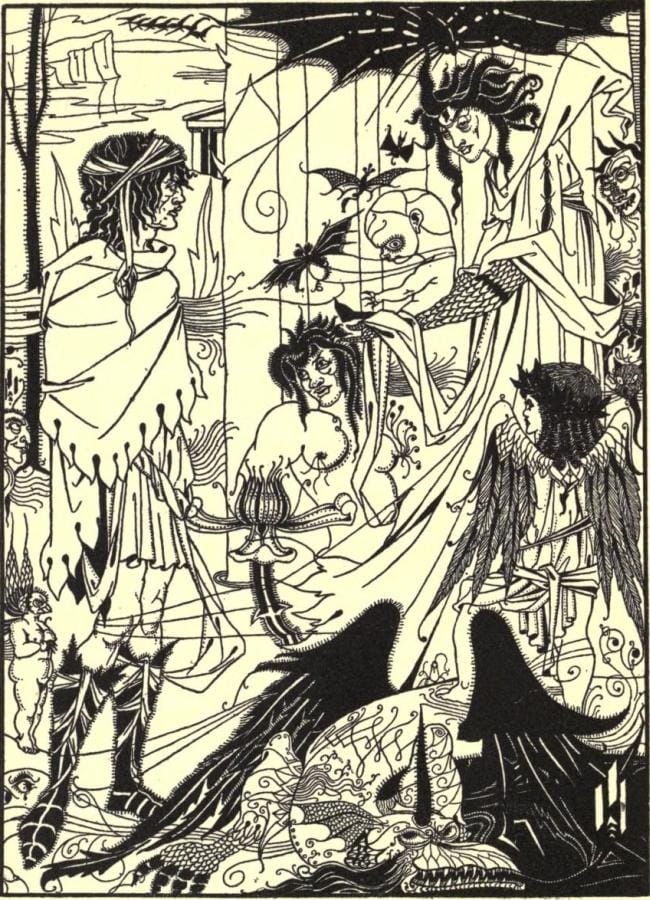

some incredible 1894 illustrations for Lucian's "True History," by William Strang, J.B. Clark, and Aubrey Beardsley

According to Lucian in the charmingly catty introduction to "True Story," he was motivated to write his knowingly nonsense travelogue because he noticed that famous authors of the past, like Homer, made up all kinds of absurdities - one-eyed monsters, hydras, enchanted potions and the like - without anyone calling them on it:

"I turned my style to publish untruths, but with an honester mind than others have done: for this one thing I confidently pronounce for a truth, that I lie: and this, I hope, may be an excuse for all the rest, when I confess what I am faulty in: for I write of matters which I neither saw nor suffered, nor heard by report from others, which are in no being, nor possible ever to have a beginning. Let no man therefore in any case give any credit to them."

Lucian's motivation feels awfully relatable to me in our current American era of culturally sanctioned bullshit, scams, and disinformation. In fact, it's poignant, as if I've reached out and touched the hand of a fellow shitposter across the centuries.

But what actually happens in "True History," in this ancient equivalent of a bitchy series of Substack posts? In the story, Lucian's long suffering voyagers must navigate visits to an island made entirely of pressed cheese, a stay in a land occupied, distressingly, by anthropomorphized dreams, and a surprisingly pleasant stay in the forested insides of a whale. Also, their little ship makes it all the way to the moon.

In Lucian's vision, the moon is occupied by an entirely male species of sentient beings, which reproduce by means of copulation with each other's legs: they feed upon frogs, have plants on their butts in the place where one might expect a tail, and have snot that is "more sweet than honey," which can be combined with milk to produce cheese. In addition to these other odd, somewhat manosphere-like attributes, these creatures have developed a technologically-enabled surveillance state:

I saw also another strange thing in the same court: a mighty great glass lying upon the top of a pit of no great depth, whereinto, if any man descend, he shall hear everything that is spoken upon the earth: if he but look into the glass, he shall see all cities and all nations as well as if he were among them. There had I the sight of all my friends and the whole country about: whether they saw me or not I cannot tell: but if they believe it not to be so, let them take the pains to go thither themselves and they shall find my words true.

While Lucian is intentionally bullshitting here, this passage presents us with another example of just how prescient his lying could be. In the 2nd century, the idea of a magical space mirror capable of reflecting back every human communication and earthly activity was inherently ridiculous. In 2025, it just reminds us of satellites, unwanted camera-on Zoom calls, and the sinister surveillance of the Trump-controlled NSA. Though we still haven't figured out how to create a species of homoerotic men that secrete honey and grow leafy plants out of their butts, so at least we've got something nice to look forward to.

Arguably, and I'm by no means the first person to argue this, Lucian is one of history's first science fiction writers. From a modern perspective, it is fascinating to consider just how someone like him, who was born in 125 A.D., was able to come up with such a modern-sounding, albeit explicitly satirical and comedic, account of what the earth might look like from above.

By saying this, I'm certainly not implying some batshit bullshit about Lucian hitching a ride on a passing UFO piloted by ancient aliens (such as, say, sexy five-eyed wolf people). The salient point is that classical-era writers like Lucian were devoting a considerable amount of time to imagining what it might be like to observe the world from above at a very great altitude, far exceeding what was possible for humans at the time.

If you believe, as I do, that imagination is a crucial part of the process that eventually leads to the development of real-world technologies, then Lucian's work is a key example of how that phenomenon works in action. He demonstrates that even during the time of the Ancient Romans, humanity had already gone pretty far down the path of being able to conceptualize what it'd be like when, about 1658 years later, the Montgolfier Brothers in France launched the very first hot-air balloon - thus finally making it possible for people to view the Earth from the same perspective as Menippus, or from the viewpoint of the moon people.

While the Pharos itself crumbled into the sea and out of popular awareness sometime in the Middle Ages, odd stories continued to circulate for many generations to come about high-up towers and fortresses that could be used for surveillance purposes, often with the aid of powerful, elevated mirrors.

assorted views of the Tower of the Winds in Athens

Sometime around 50 B.C., during Rome's lengthy period of rule over the once-mighty city of Athens, the Macedonian astronomer Andronicus of Cyrrhus constructed a really weird little octagonal tower in the midst of the city's forum.

Today, we call it The Tower of the Winds. And I love it very much.

Constructed of marble and reaching a height of 36 feet, each wall of the Tower of the Winds has a carved portrayal of a winged figure representing one of the eight winds recognized in antiquity, and beneath each figure, there was once a sundial. On its roof, according to the Roman writer Vitruvius writing in the year 27, it once featured "a brazen (bronze) Triton with a rod in its right hand moved on a pivot, and pointed to the figure of the quarter in which the wind lay."

While the outside of the building was impressive, most ancient sources assert that the inside was even more interesting. According to the writer Varro, writing in 37 BC, the building contained an ingeniously engineered water clock:

"Inside, under the dome of the rotunda, the morning-star by day and the evening-star at night circle around near the lower part of the hemisphere, and move in such a manner as to show what the hour is. In the middle of the same hemisphere, running around the axis, is a compass of the eight winds, as in the horologium at Athens, which was built by the Cyrrestrian; and there a pointer, projecting from the axis, runs about the compass in such a way that it touches the wind which is blowing, so that you can tell on the inside which it is" (On Agriculture, III.5.17).

Probably, the Tower was constructed as a high-tech demonstration of the ancient meteorological and horological arts, a centralized and expensive weather station many generations before we invented both the Weather Channel Local on the 8s and smooth jazz (though I guess the Romans had some musical equivalent of smooth jazz, which is also going to keep me up at night).

What is definite is that the Tower of the Winds is unusual, and this has provoked travelers throughout the centuries to come up with other interpretations for how it was used. These include the Ottoman Turkish travel writer Evliya Çelebi, a rather fun-sounding guy who spent more than 40 years wandering around his native Turkey, Europe, and Asia, jotting down trenchant comments on what he saw as he went.

In 1668, Celebi turned up in Athens, which was at the time controlled by the Ottoman Empire Like the the rest of us, he was impressed by the Tower of the Winds, and he devoted a lengthy passage to it in his records, ascribing magical powers to the place that do not, for some reason or another, come up in the more austere descriptions of the buildings from ancient Roman sources.

According to Celebi, in ancient times:

"...the learned men in the city devised for it a different sort of strange talismanic protection, marvelous to relate. Each day, one of them created a talisman of surpassing wondrousness, so that in this city, it is said, there were no plagues, snakes, centipedes, scorpions, storks, crows, fleas, lice, bedbugs, mosquitoes or houseflies."

Unfortunately, these talismans lost their effectiveness on the very day when "the Apostle of God emerges from his mother's womb," which is why Athens still has crows and mosquitoes today, as I can personally verify.

More relevantly for us, Celebi also claims that the Tower once contained a far-seeing mirror, which essentially functioned as a homeland security system for the Athenians of old.

Celebi writes:

On the outside of this marble pavilion-dome there is a thin pivot, and in the days of the learned ancients they say that there was a mirror of the world set on this pivot, like the mirror of Alexander [on the Pharos]. And they say that whenever an enemy started out against the city from anywhere in the world, the enemy army, as it marched, was revealed along with its commander in this mirror of the world. The place for the mirror remains, but the mirror is no longer there.

Improbably, and very luckily for us, the anomalous wonder that is the Tower of the Winds has survived largely intact into the modern day. I visited it myself in 2024, where I joined the tourists going inside of it (where you can view the shockingly well-preserved ceiling, and the channels the water-clock once used), going outside of it again, and then cocking their heads in its general direction and going "huh." It's just the kind of building that makes you go "huh." You should go see it sometime.

It is unclear where, exactly, Celebi got his idea about the Tower of the Winds and its accompanying security mirror. But we encounter a not dissimilar-sounding device a bit further back in time, within the various incarnations and iterations of "The Seven Sages of Rome" or "The Seven Wise Masters," a pre-modern story cycle that likely first originated long ago somewhere in the East, possibly in 1st century BC India.

From this starting point, this group of associated stories, usually given an ancient Roman framing to knit them all together, spread across the world of the Middle Ages in an enormous number of different languages and interpretations. While sadly little-known today, these tales were incredibly popular entertainment during their era, amusing people across continents and cultures. Many of these stories, given their Roman framing, dig into the rather fan-fiction like adventures of famous figures from the more distant past, such as the Ancient Roman writer Virgil.

In some of these Virgilian legends, according to a summary offered by the excellent Seven Sages of Rome research database, the story describes a magical mirror built by Virgil for the Roman Emperor, which constantly reflects the far-off image of those who might seek to harm Rome. Often, but not always, this mirror is described as being set upon the top of a high-up pillar.

However, an enemy king offers a reward of gold to anyone who might destroy the mirror, and two men take him up on it. But instead of straight-forwardly attacking the Emperor like more normal, stupider people would do, the two would-be assassins trick him by playing upon his greed: they pretend to be skilled treasure hunters, and convince the Emperor that there is gold buried beneath the magical mirror. The Emperor duly digs it up and destroys the mirror, which angers the Roman people so much that they "turn on the emperor, and kill him by pouring molten gold into all his orifices." (Gross!)

I'm not exactly great at reading Middle English, but you can probably get the gist from one old version of the text, as compiled by Killis Campbell way back in 1907:

Here's another Middle English version of the Virgil tale, as edited and interpreted by Jill Whitelock in 2005:

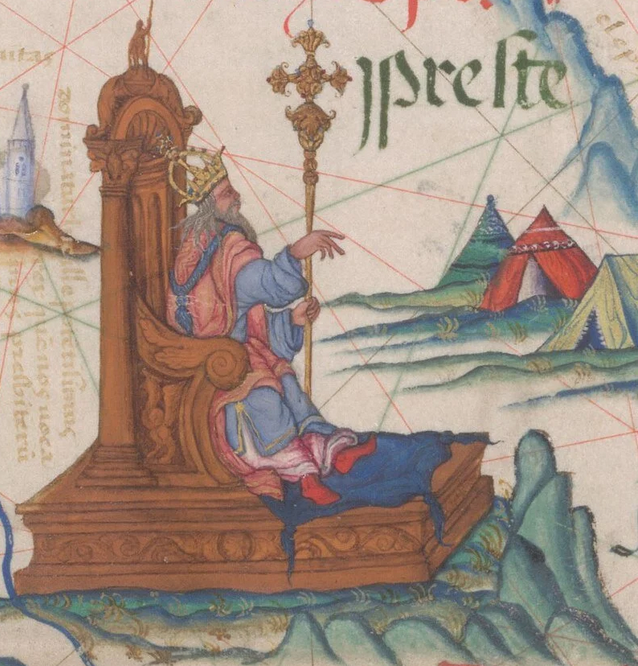

During the age of the Crusaders, the same population of Europeans that circulated the legends of the Seven Sages were similarly fascinated by stories about a mysterious king named Prester John, whose legend appears to have sprung to life sometime around 1145.

According to these stories, Prester John conveniently ruled a previously unknown and fabulous wealthy Christian kingdom, located in a never totally specified location somewhere in far-off Asia or, later on, Ethiopia. Equally conveniently, according to most accounts, Prester John was an eager ally with the Crusader's doomed effort to take back the Holy Land from its Muslim occupants, and was even rumored to have defeated Persia's Muslim kings in a pivotal battle not long ago.

While it is unclear exactly who he was supposed to be, some suspect that Prester John represents a very garbled interpretation of the Nestorian Christian minority that lived among the largely Buddhist Khitan people of the Central Asian Qara Khitai empire = who really did defeat Sanjar, a Seljuk sultan, at the Battle of Qatwan in Uzbekistan in 1141.

Prester John may also reflect more generally-applied European wishful thinking about the ultimate goals of the Mongols, during the early years of their period of ferocious global expansion. Tellingly, he emerges at that optimistic point in history when rumors first began to slowly trickle back towards Europe of how the Mongol armies (whose ranks did also include Nestorian Christians) had successfully crushed a succession of Muslim rulers in Central Asia and the Middle East.

Prester John as Ethiopian emperor from a French publication in 1684, Prester John in the Queen Mary Atlas of 1558, and Prester John in a 1400s edition of Marco Polo's journeys.

However, misplaced European optimism about Mongol intentions rapidly faded after it it became hideously apparent by the 1200s that the Mongols weren't, as the Westerners had hoped, heading to Jerusalem to liberate it for Christ - instead, the steppe armies were coming for them next.

But the tale of Prester John was nothing if not flexible, and Europeans rapidly adapted the legend of a sympathetic and geographically isolated Christian king to whatever circumstances they found themselves in, keeping the dream alive that he might ride to the rescue of Christendom against their Muslim rivals any day now. Ultimately, people would keep believing in Prester John for six centuries, all the way up into the 1600s, making his legend on of history's most enduring, and wishful-thinking propelled hoaxes.

One such Prester John yarn comes to us in the form of a supposed 12th century letter, which claimed to be written to the Byzantine Emperor by Prester John himself. While scholars continue to debate who actually wrote it and why, at the time, it became something of a medieval literary sensation, copied and circulated throughout Europe for centuries, and occasionally embellished upon for added effect.

In the letter, the purported Prester John somewhat unctuously describes the magnificence and power of his Christian kingdom in considerable detail, touching upon its great size, its remarkable wealth, its holy and ethical people, and even its wildlife, which includes dog-headed men, white bears, aurochs, phoenixes, and giants "whose height is forty cubits."

(The letter also very specifically cites as a perk that in this land, no "noisy frog croaks" - were people back then generally upset about frog noises, or was that more of a pathology of the author? This is going to keep me up at night).

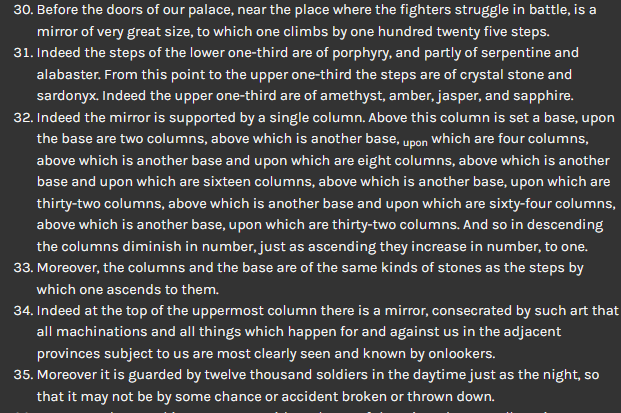

Amidst detailed descriptions of the bejeweled wonders of Prester John's palace, the author describes an enormous, elevated, and elaborate mirror, mounted upon a column:

This account sounds not dissimilar to the mirror on a column in the "Seven Sages," and it sounds similar again to that of Celebi. In their turn, they all sound a lot like the Pharos, and to Lucian's own, likely Pharos-inspired account of a race of plant-tailed moon people with a magic palace surveillance mirror.

It's completely impossible to say how much all of these stories have to do with one another, and I have no desire to make a bunch of classicists and historians mad at me. But it would also be a little bit funny if Lucian's constantly-circulated shitpost of a story, explicitly intended to poke fun at the overly credulous, inadvertently helped to usher in more than a thousand years of rumors about magical world-viewing mirror. And I think he would have found that pretty hilarious too.

Although mirrors capable of feats of remote sensing that would be impressive today almost certainly didn't exist in ancient times, we know that tall towers did, and that they served their purposes of both surveillance and symbolism very well for their builders. And yet, impressive as these very real monuments were (and are), they have a number of obvious drawbacks for the discerning ruler, warlord, or poet.

After all, such structures are inherently and inconveniently stationary, condemned forever to gaze out upon a singular view. You can't exactly pop a step pyramid in your pocket, or cart an unattended ziggurat off as a prize during war.

Enter more portable forgotten technologies and specialist techniques for peering far beyond the limits of human sight. Not quite drones, no - but crucial stepping-stones alone the way to dreaming into them being.

Here are the entries in this series so far:

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Preface

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: A Drone of The Mind

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Forgotten Technologies, Towers, and Roman Shitposting

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Death Rays, Brass Horses, and Dragon-Surprising Mirrors

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Pondering Orbs, Black Mirrors, and World-Viewing Cups

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Tower-Jumpers and Hungry Eagles