The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Pondering Orbs, Black Mirrors, and World-Viewing Cups

Staring into the mysterious depths of a sacred water-filled cup. Lighting a match in front of a mirror round' midnight. Pondering an orb at the top of a sweet-looking tower. These atmospheric activities all involve objects that humans have, at some point, believed could be used by certain magically-talented specialists to seek hidden information beyond the physical boundaries of reality

The practice and ritual of "scrying" concerns seeking hidden revelations about the future, the present, and the past by gazing intently into the reflective surface of something, such as a crystal ball, a water basin, a shining sword blade, or a mirror. Certain categories of items are so commonly used for this purpose that they've inspired new terms unto themselves: "catoptromancy" refers to using a mirror for divination or scrying purposes, while "crystallomancy" refers to using crystals (such as, say, in the context of a crystal Pondering Orb).

Although the term "scrying" appears to have first popped up in English around 1520, we know for an absolute fact that the practice is much, much older than that. Scrying-like activities took place in ancient cultures ranging from Egypt to Sumeria to China to Central America, spanning a remarkable number of different peoples and religious traditions.

We have long been channeling our uncertainty about the inherent weirdness of reflective surfaces (as discussed in the first part of this series) into magical rituals geared towards seeing things that are happening far beyond both our physical location and our current position in the fabric of time itself.

Nor is scrying dead. Far from it. The practice has very much lived on into the present, to such an extent that you can still sign up for scrying classes at various New Age centers around the world. Search engine queries for "how to scry" returns both very sincere introductions by people who consider themselves to be modern magicians, as well as an impressive amount of AI-generated slop professing to provide a LLM perspective on delving into the spirit world. (God help us all).

For a mere $84.99, you can buy your occult-minded child an electronic "Magic Mixies" crystal ball, whose swirling and inscrutable mists will reveal a pastel-colored plush animal capable of, I would hope, telling you the exact moment and hour of your death. There's even a so-called Fully Accredited Scrying Diploma Course on offer on Udemy, recently discounted to $16.99 from $39.99 - and hey, what price can one really put on supernatural information?

The world historical record contains a truly staggering number of stories, ideas, and accounts of scrying practices, and I won't attempt to cover all of them here. Down that path lies madness, or at least, a PhD thesis that absolutely no one is actually going to grant me a degree for (much less funding). But there are a select few examples that I find particularly interesting for the purposes of our journey through the ancient imagination, and the ideas that would eventually lead to modern-day drone technology.

One such object is the "world-revealing cup" of Persian myth and tradition.

A scrying-like device appears in the Shahnameh (“Book of Kings"), a Persian epic poem dated to between 977 and 1010 CE, and written by the great Iranian poet Ferdowsi. One of the longest epic poems ever written, and the longest known epic poem by a single author, it tells a sweeping story, populated by an enormous number of characters, that manages to cover everything from the creation of the world itself all the way up to the arrival of Islam.

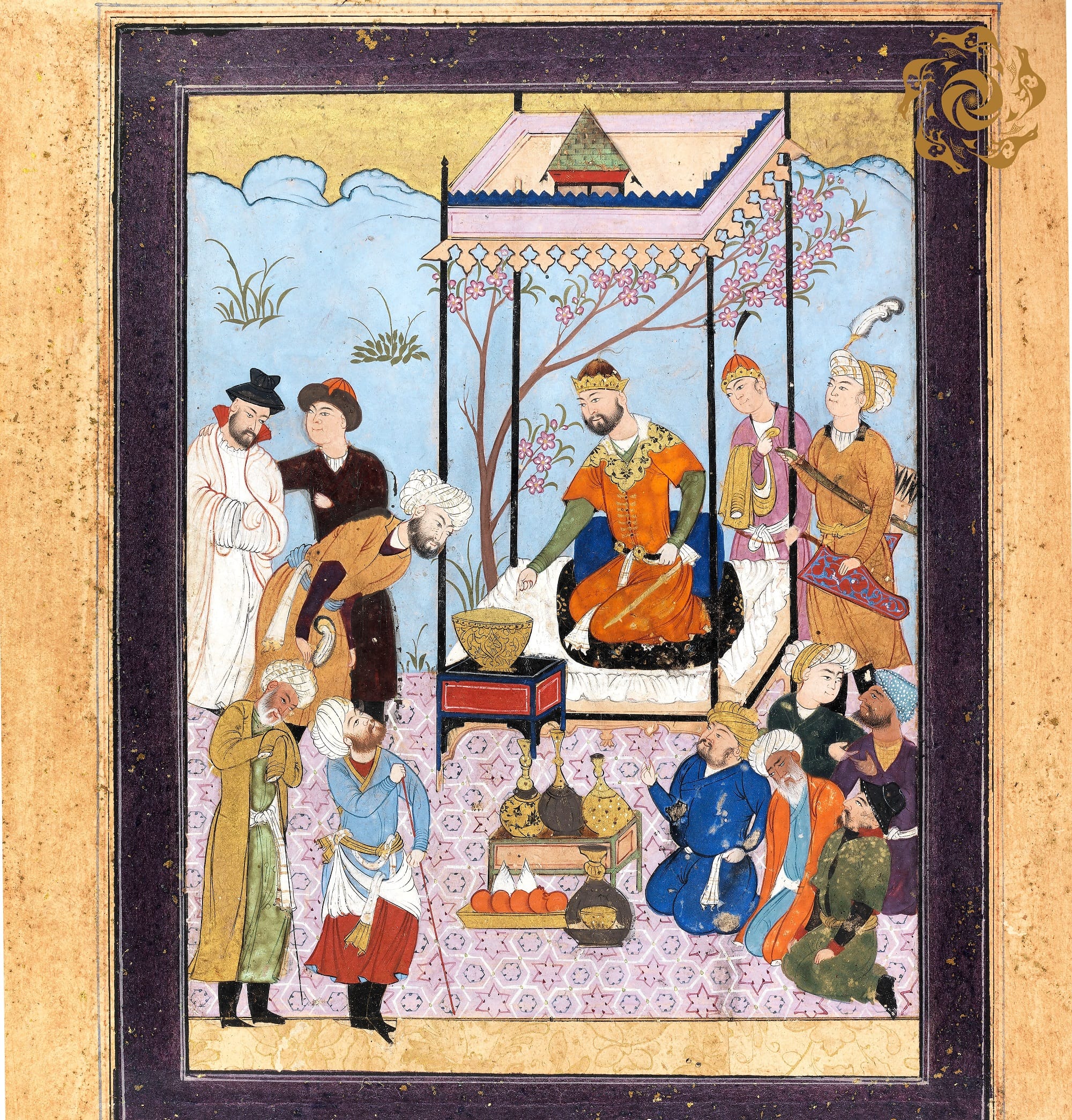

The epic also features a magical object that appears quite frequently in other works of Persian literature and myth: a magical "world-viewing" cup, often referred to as the "Cup of Jamshid." Importantly, unlike the other magical devices we've touched upon previously, the Cup is imbued with considerable spiritual and ceremonial meaning: its use is reserved by God for the worthy and (usually) for the royal.

Within the Shahnameh, the king and seer Kay Khosrow makes use of this cup to search for the missing son of one of his allies. Here, I am using the Dick Davis translation, published by Penguin:

"I shall have the world-revealing cup that shows the seven climes brought to me, and I shall invoke God’s blessings on our noble ancestors. Then I will tell you where Bizhan is, since the cup will answer my prayers.”

What does Kai Khusrau actually see in there?

"He cried out to God, calling down blessings on the sun as it inaugurated the new year, and asked for strength and help to defeat the power of Ahriman. Then he returned in solemn procession to his palace, replaced the crown on his head,and took the cup in his hands.

He stared into it and saw the world’s seven climes, the turnings of the heavens, all that happened there, and how and why things came to pass. He saw from the sign of Pisces to that of Aries, he saw Saturn, Mars, the sun, Leo, Venus, Mercury above, and the moon below. The royal magician saw all that was to be seen. Searching for some sign of Bizhan, his gaze traversed the seven climes until he reached the land of the Gorgsaran,and there he saw him, bound with chains in a pit, longing for death; beside him princess Manizheh stood, ready to serve him."

The Cup also rates a mention in the Sawānih, Ahmad Ghazālī's famous work of transcendental Sufi love poetry from the 11th century:

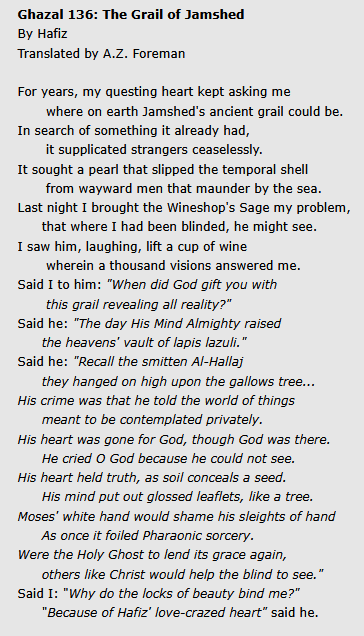

The beloved medieval Persian poet Hafez, who lived and wrote in the 1300s, also used an individual's fruitless search for the Cup of Jamshid/Jamshed as a potent metaphor (one that is far above my pay-grade to provide a solid interpretation of - I will direct you to the writer Ali Hammoud's excellent newsletter for that). Per an English translation very kindly provided to the Internet by A.Z. Foreman, Hafez's Ghazal 136: The Grail of Jamshed goes like this:

Considerable debate still surrounds what the "world-viewing cup" actually looked like, or if it was even a cup at all. Some translators and Persian scholars have construed it as more of a crystal ball - and one modern Iranian optometrist has even proposed that the poets of old were actually describing spherical crystals that could be used to correct eyesight.

During the Middle Ages in Europe, mirrors could function both as as magical objects and as highly profitable mass-market souvenirs. Starting in about the fourth century A.D., some European Christians began to embark on pilgrimages from their homes to key religious locations, such as the iconic sites of the Holy Land and the mighty tombs of martyrs and apostles in Rome.

In the year 814, the mortal remains of the apostle Saint James just happened to be re-discovered at Santiago de Compostela in Northern Spain, at a period in time that just happened to be not long after the Muslim conquest of the vast majority of the Iberian Peninsula. The year 814 also marked the death of the mighty Frankish king Charlemagne, who had only a few years before received a number of holy relics from Jerusalem, which he installed with great ceremony in his royal chapel at Aachen in what is now modern-day Germany.

These events would turn both Santiago de Compostela and Aachen into crucial pilgrimage sites for European Christians, a medieval spiritual tourism trend which would reach its apogee in the 11th and 12th centuries, although on-foot pilgrimages to these sites continue to be very popular among both the religious and the merely curious today.

Just like the tourists of today, the medieval era's wandering pilgrim hordes loved collecting souvenirs - and in turn, medieval entrepreneurs loved selling them mass-produced knick-knacks. Enter the pilgrim badge, the commemorative shot glass/fridge magnet/snow globe of Ye Olden Days.

pilgrims with badges on their hats by Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533), an Aachen mirror pilgrim badge from 1350 to 1400 likely similar to those sold by Gutenberg, and a Bruges pilgrim badge from 1375 to 1450 with some aristocratic genitalia

While these metal badges often depicted the expected G-rated Christian themes, almost as often, they were absurd, weird, and downright obscene (much like the fridge magnets of today), ranging the gamut from vaginas decked out in touring attire to lovingly-detailed renderings of dicks with wings. Wildly popular, pilgrims badges were produced in the millions, and so many of these doo-dads survived into modern times that you can easily buy a genuine medieval specimen for a few hundred bucks on the Internet.

You've probably heard of one of these vendors of pilgrim badge crapola. His name was Johannes Gutenberg, and he's the guy who invented the printing press.

Specifically, Gutenberg was selling Aachen pilgrims what was a clever innovation in 1400s consumer technology: badges with mirrors stuck in them, which were pitched to the public as capable of "storing" the reflected essence of a saint's relic.

By this ingenious pre-photography conceit, a common souvenir could be imbued with great spiritual power, which pilgrims and their loved ones could then draw upon after returning home to their normal lives. This technique also supported the continuing survival of the relics themselves, as they provided pilgrims with an appealing alternative to actually physically touching these sacred objects (with their oily little paws) to come away with a bit of their power.

According to this source, it is quite plausible that Gutenberg got the idea for the printing press in the course of his work developing casting molds for metal pilgrim badges - which would mean that the entire Western literary world owes a massive debt to the popularity of a tchotchke with a mirror stuck in it.

And so, of course, do drone cameras, which are merely our latest innovation in the arena of capturing light to store the essence of objects we can't actually touch, holy or otherwise.

the Aztec deity Tezcatlipoca, Aztec codices describing mirrors, a Maya "mirror-bearer" carved wooden sculpture from the Early Classic period (250-550 CE), now in the collection of the Met in New York City.

In many cultures in the ancient Americas, religious practitioners used mirrors for various spiritual and ceremonial purposes, imbuing them with what we can presume was intense symbolic meaning. In one of the first major Mesoamerican civilizations, that of the 1200 to 400 B.C.-era Olmecs, mirrors appear to have been quite popular: archaeologists have found that some concave Olmec mirrors still work well today.

In the culture of the Mayans, the Classical-era deity Kawil was linked with fate and the ability to predict the future by means of a supernatural "smoking mirror." Mirrors also appear as a common motif among the ruins of the mighty culture of Teotihuacan, where pyrite mirrors appear to have been used as popular costume elements, worn at the small of the back, on the chest, and in headdresses.

As the people of Teotihuacan left no written records, it's hard to concretely say more about the symbolic or religious purpose of mirrors in their culture - but it is clear from surviving visual art that they were associated with eyes, faces, and passageways (among other elements), indicating a link to practices of divination.

Amongst the Aztecs, the deity Tezcatlipoca's name translated into "smoking mirror," evoking the black obsidian mirrors that he was commonly portrayed with in surviving codices. Tezcatlipoca, who is likely derived from earlier Central Mexico deities that in turn influenced the Mayan Kawil, played a key role in creation mythology, functioning as a "master of fate" and a cunning trickster. According to an account from the Franciscan missionary Fray Bernadino de Sahagún, the god's "abode was everywhere... in the land of the dead, on earth, [and] in heaven."

Another account from Bernardino de Sahagun in his "Florentine Codex" claims that the Aztec’s final ruler, Moctezuma II, was exposed to a series of distressing omens in the decade leading up to the brutal Spanish conquest of his empire. The seventh such omen, arguably the weirdest, involved a weird bird with a mirror on its head;

The seventh omen came when water people were hunting or snaring and captured an ash-covered bird, like a crane. They went to the Tlillan calmecac to show it to Moctezuma; it was past noon, but still daytime. On top of its head was something like a strange mirror, round, circular, and it appeared to be pierced in the center, where one could see the sky, the stars, and the Firedrill [mamalhuaztli or Caster and Pollux constellation].

Moctezuma took it as a great and evil omen when he saw the stars and the mamalhuaztli. And when he looked at the bird’s head a second time a little further, he saw a crowd of people coming, armed for war on the backs of deer. Then he called for the soothsayers and sages, and asked them: “Do you not know what I have seen? a crowd of people coming.” But when they began to answer him, all had vanished, and they could tell him nothing more.

And indeed, this is exactly what came to pass: the murderous Spanish arrived at the gates of Tenochtitlan in 1521, riding upon the backs of animals that appeared to the Mexica people as akin to enormous, antler-less deer. All was lost.

In one of the odd cross-over episodes that history not infrequently confronts us with, one such Aztec spirit mirror made it into the hands of the 16th century English scholar, occultist, and ceremonial magician John Dee, who served as a personal advisor and friend to the magically-inclined Queen Elizabeth I. In 2022, researchers determined that Dee's magical mirror, long on display in the British Museum's Enlightenment Gallery, was in fact crafted by obsidian collected from a mine within the bounds of the Aztec empire.

Like many other intellectual men of his era, in a time well before our modern delineations between science and pseudoscience became clearly drawn, Dee worked in in everything from mathematical ship navigation to astrology to engineering. His mechanical abilities were such that he is said to have constructed, while still a student at Cambridge, a mechanical dung beetle for a stage show that was so startlingly convincing that some onlookers darkly suspected that he had sold out to the Devil to construct it. (Some people sell their souls to the devil for money, some for power, and some for a real big mechanical bug for a student play, as the saying goes).

As both Dee's court influence and his bank account diminished in the early 1580s, he began to more seriously consider the intriguing possibilities of contacting the angels of the spirit world by means of scrying. As Dee wasn't much of a scryer himself, he worked with other mediums to consult these alleged angels - and eventually, in 1582, he would launch an allegiance with the then 26-year-old Edward Kelley, a somewhat dissipated-looking character with a drinking problem, whose ears had been previously cut off as a punishment for counterfeiting.

The angels (or Kelley, oh gosh, who can say!), would proceed to give Dee a bunch of incredibly terrible political advice, which sadly made the rapidly weirdening sorcerer yet more unpopular among the Tudor elite. By 1583, both men and their families would leave England and start a nomadic life of freelance crystal viewing, experimental alchemy, and a little light necromancy, in the older meaning of attempting to communicate with the dead. It is likely that the black Aztec mirror accompanied the men on their magical mystery tour across the more gullible courts of Renaissance Europe, serving as one of the conduits by which they might contact the "angels" that Dee (at least) ardently believed in.

Eventually, the increasingly audacious Kelley would claim to Dee that the angels had told him that he "who commits adultery because of me, let him be blessed for eternity and receive the heavenly prize," a directive that Kelley emphatically interpreted as requiring the two men to swap wives. While both Dee and his own spouse found this prospect deeply unappealing, they reluctantly complied anyway.

Not long after, the somewhat chastened Dee and his family managed to escape the clutches of their increasingly toxic angelic polycule, leaving Kelley to his Continental future of professional alchemy, fame, and eventual death by flinging himself out of a window to escape the clutches of the law.

Back in England, the now-aged Dee turned once again to scrying and the advice of the angels, eventually perishing not long after the angel Raphael told him that he would soon be taking "a long journey in hand, and go where thou shalt have all of these great mercies of God performed unto thee." He remained a true believer in the supernatural communication powers of weird mirrors up until the end.

Although some traditions, like Persian mythology, tend to view the "world-viewing" cup with uncomplicated reverence, the art of scrying was often viewed as ethically fraught, if not actively fraudulent, in other times and in other places.

Perhaps no example of this is better known than the story of Snow White, which the Brothers Grimm first collected in early 19th century, but doubtless dates back further. The Evil Queen uses her mirror as an all-purpose surveillance device, relying upon it to monitor Snow White's movements. The tale thus deftly links together two ancient concerns about the general misuse of mirrors: in the service of female vanity, and as tools for supernatural surveillance.

Far further back still, the Bible and the Torah come out against the magical arts (including divination) rather harshly indeed, like in Deuteronomy 18:10, which states:

There shall not be found among you any one that maketh his son or his daughter to pass through the fire, or that useth divination, or an observer of times, or an enchanter, or a witch,

So too, did Saint Augustine, in his 5th century "City of God," where he rails with characteristic humorlessness against the "pestiferous and accursed" practice of magic. According to him, divination and other such attempts to supernaturally view the unseen were in fact almost always mechanisms by which sinister demons could prey upon mankind:

As to those who perform these filthy cleansings by sacrilegious rites, and see in their initiated state (as he further tells us, though we may question this vision) certain wonderfully lovely appearances of angels or gods, this is what the apostle refers to when he speaks of “Satan transforming himself into an angel of light.” For these are the delusive appearances of that spirit who longs to entangle wretched souls in the deceptive worship of many and false gods, and to turn them aside from the true worship of the true God, by whom alone they are cleansed and healed, and who, as was said of Proteus, “turns himself into all shapes,” equally hurtful, whether he assaults us as an enemy, or assumes the disguise of a friend.

However, there's some wriggle room, as we see in Genesis 44, which contains a curious passage in which Joseph, testing the morality of his brothers, appears to imply not just that he practices divination with a magical cup, but that God is not - at least in his case - particularly bothered by this.

Augustine himself makes a similar observation in "City of God," as he considers the wonders performed by Moses to rescue his people, as opposed to the dark magic of the Egyptians:

"They did these things by the magical arts and incantations to which the evil spirits or demons are addicted; while Moses, having as much greater power as he had right on his side, and having the aid of angels, easily conquered them in the name of the Lord who made heaven and earth."

The implication largely seems to be that divination and other magical acts of surveillance are not always evil, but that their morality is exceedingly dependent on the moral fiber and intentions of the magic-doer in question. And almost always, that person will not be strong enough to resist the demon hordes always-lurking, always-present fondness for tormenting mortals - including via the portal-like mechanisms of mirrors and crystal balls.

How these observations relate to how modern surveillance technologies (like drones) are used today is an exercise I will leave, for now, to the reader.

Many generations before the rise of surveillance capitalism, the NSA, and Mark Zuckerberg's obscenely stupid data-collecting Ray-Bans, the 12th century Christian scholar John of Salisbury was ruminating darkly about the ethical and spiritual ramifications of scrying in "Polycraticus," his landmark, exhausting, political text.

As a child, he had been placed in the care of a suspicious priest who practiced the art of crystal gazing in his free time: as it was believed that children were better at it than adults, the priest occasionally pressed an appalled young John into scrying service, eventually giving up after the boy asserted that he could see nothing in the darkness. He writes:

"Crystal seers falsely flatter themselves that they offer no sacrifices, that they harm no one, that often they are helpful in detecting theft and purging the world of malefactors, and that they seek only truth that is helpful and practical. The wicked are not so. "He that gathereth not with me" He said "scattereth, and he who is not with me is against me." In practicing such arts despite the prohibition of God, what else are the wicked doing than lifting up the heel against Him who prohibits them?"

And if that's not enough, John would also like the reader to know that scrying, much like masturbation, will probably strike you blind:

"But as I grew older more and more did I abominate this wickedness, and my horror of it was strengthened because, though at the time I made the acquaintance of many practitioners of the art, all of them before they died were deprived of their sight, either as the result of physical defect or by the hand of God, not to mention other miseries with which in my plain view they were afflicted."

a smug nun demonstrating a magic lantern (Bacon probably didn't actually invent it) to some idiots, Roger Bacon with a telescope, and Roger Bacon looking pretty burned out in a relatable way.

Roger Bacon - here he is again! - was supposedly arrested for his philosophical and astrological activities sometime around 1277, though it is highly debatable if this actually happened, or was merely an invention of the body of literature that sprang up around him after his death. And there was a lot of that literature. Although Roger Bacon himself scoffed at practitioners of what he deemed to be "magic proper" (accomplished with the help of demons), which he viewed as inferior to "natural" demon-free magic, many later writers would cast Bacon as essentially a morally ambiguous medieval wizard.

Still, even in the royal courts of Tudor England, a person like John Dee could manage to not just survive but actively thrive as a scryer, astrologer, and public magician. While in 1555, Dee experienced a close call after he was accused of using witchcraft to create horoscopes for both the then Princess Elizabeth and of Queen Mary, he was later exonerated. John Dee himself would later write defenses of Roger Bacon, identifying with a fellow scholar whose efforts had, at least allegedly, been sorely misunderstood in his own lifetime.

Dee's story presents further proof that while the practice of surveillance through both practical and magical means has always been controversial and contested, it has rarely been entirely discarded or condemned. It is simply far too useful for that.

And so it still goes with us today, in our current era of rampant big-tech data harvesting, rapidly proliferating surveillance cameras, and (of course) the en-masse adoption of surveillance drones by both the powerful and the powerless.

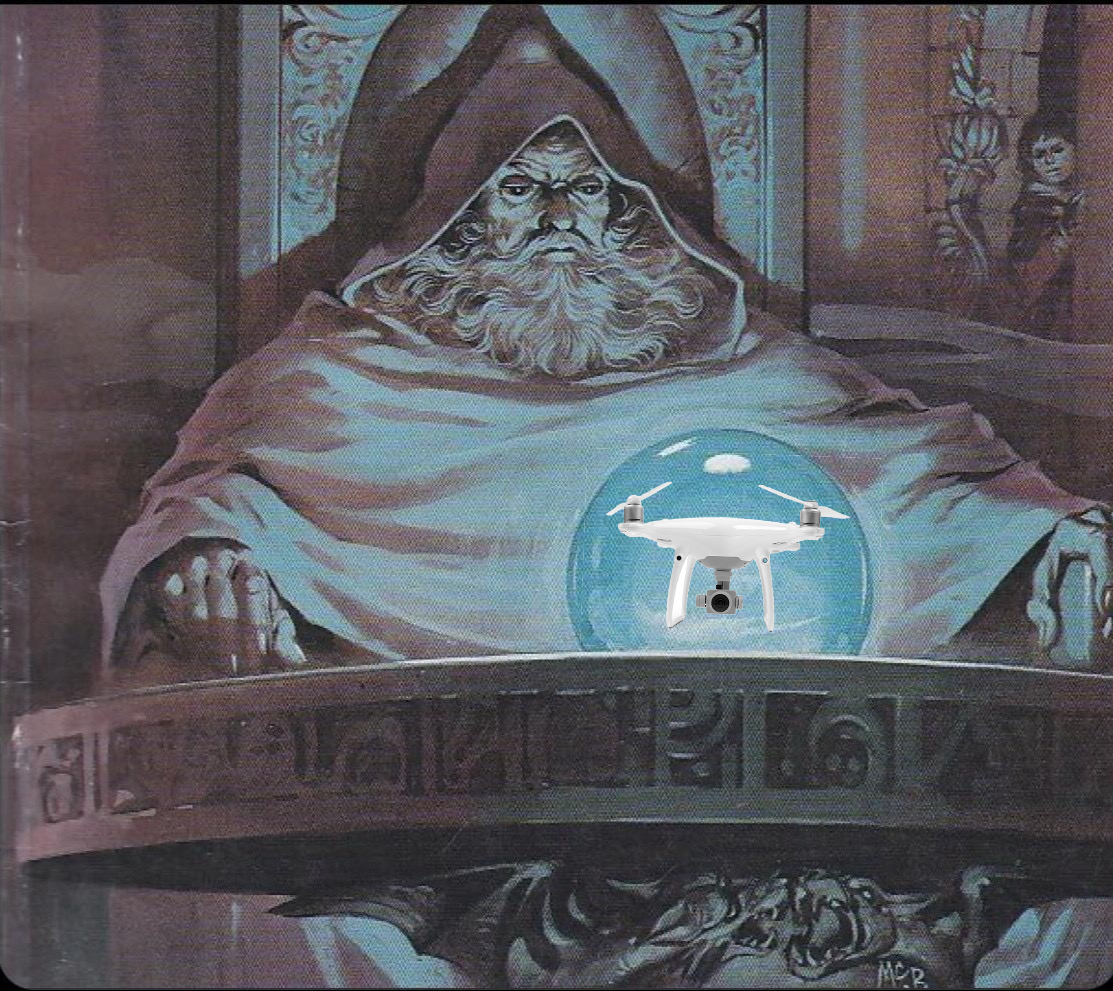

The moral ambiguity that surrounds scrying, magic mirrors, and other antique surveillance technologies also remains very familiar, not least due to the immense popularity of J.R.R. Tolkien's "Lord of the Rings." Within both the original text and in the series of films, the palantíri, a set of elven-made "seeing stones" that can be used for both global surveillance and for communication, are presented as deeply ambiguous and inherently dangerous objects. (The renowned elven leader Galadriel also makes use of a magical mirror for divination, which is treated in the text with similar complex themes).

In Tolkien's fictional world, he seems, unsurprisingly, if you know his background, to view these tools for divination in a rather similar light to that of Saint Augustine. The palantíri and the mirror are objects that certainly can be used for noble purposes by those imbued with wisdom and strong will - but they also can easily be appropriated by dark forces to entrap and pervert the psyches of those with weaker minds and a more easily exploitable lust for power.

Throughout Tolkien's text, it is made quite clear that while the palantíri are not exactly inherently evil, it is also for the best that they be used as rarely and as carefully as possible, and only then by a very small subset of exceptionally strong-willed and trustworthy individuals. Just as Moses was that rare specimen capable of harnessing magic for holy ends, so too does it require someone as supremely strong-minded as Galadriel to make use of a divining tool without incurring horrible consequences.

In accordance with Silicon Valley's tradition of completely missing the point of works of fantasy and science fiction, a bunch of power-hungry techbros decided to name their egregiously evil surveillance company "Palantir" anyway. We don't know how this particular, ongoing shitshow of a story is likely to end, but if we consider what happened to Saruman, we can take an educated guess.

As a species, we are in the midst of fucking around with often deadly powers of surveillance, abilities that our ancestors - who could, at the time, only really imagine them - regarded with a sensible mixture of both awe and apprehension.

Eventually, one way or another, we are going to find out.

Here we come to the end of my account of the first dream that humanity needed to have before we could build a modern drone: the dream of viewing things very far away from our physical bodies.

The second part of this series will address a second, and equally elemental human dream - the dream of achieving flight.

Here are the entries in this series so far:

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Preface

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: A Drone of The Mind

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Forgotten Technologies, Towers, and Roman Shitposting

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Death Rays, Brass Horses, and Dragon-Surprising Mirrors

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Pondering Orbs, Black Mirrors, and World-Viewing Cups

The Three Dreams You Need to Make a Drone: Tower-Jumpers and Hungry Eagles