The Virtual Pet Games of My 90s Youth and AI Ethics: Some Thoughts

Back in the 1990s and early 2000s, back when I was a mere dweeby child, there existed a tween-driven online social movement against the cruel practice of abusing pets.

This movement was not about the abuse of living, flesh and blood pets (although I'm sure its proponents weren't keen on that either).

This was social action against the abuse of virtual pets.

Specifically, against the abuse of beguilingly realistic dogs and cats composed of 3D balls that lived on your computer, in the original Dogz and Catz series of video games released by P.F. Magic from 1995 to 2002.

this is Proustian for me

The Petz games of my youth spawned a large and fascinating video-game subculture dominated by women, girls, and queer people - a fandom that still exists, albeit to a lesser extent, today. [[1]] These fans maintained a host of Geocities and Tripod websites where fellow enthusiasts could swap Petz, download creative game mods, participate in shows, and, as has proven perennially popular on the Internet, argue with each other.

Many of these Petz websites hosted pages and banners dedicated to fighting what their kid administrators believed was a genuine social problem: stopping Petz abuse.

The community largely defined Petz abuse by the overuse of the games spray bottle tool, which players could use to punish their virtual animals for unwanted behavior. Petz sprayed with the tool exhibited upsettingly realistic behavior, including yelping, screaming, and cowering in fear, as is depicted in this interestingly avant-garde YouTube video:

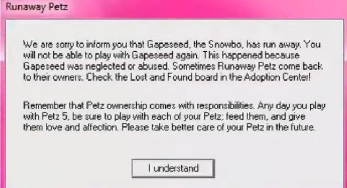

In these games, Petz couldn't die. But, as is the case in both real life and in virtual pet games, there are fates arguably worse than death.

If squirted with the spray bottle enough times, or if ignored by the player for a long enough period, a given Petz internal Neglect score might reach such a point that the game would designate them as a "Runaway," freed forever from their owner's tyrannical influence. (Well, technically - it was possible to edit the Petz file directly to get them back).

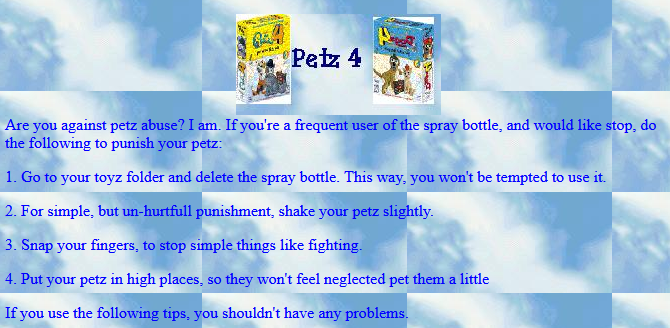

Many prominent members of the Petz community took abuse deadly seriously, although it was effectively impossible to determine if another Petz player was, in fact, engaging in the dreaded practice. Some even held the view that users should delete the squirt bottle from their installation of the game entirely, thus entirely removing the temptation to inflict pain on a virtual dog.

While anti-Petz abuse advocates were aware that their virtual pets weren't real, from their point of view, this was largely immaterial: as one widely-used banner pointed out: "Just because they live in a computer...doesn't give you the right to abuse them."

Some observers questioned why game-makers P.F. Magic had placed what could be construed as an animal-abuse mechanism into a children's game in the first place. Were they, in a sense, encouraging kids to torment little virtual animals?

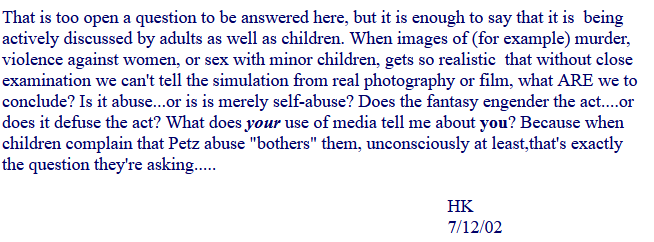

In 2002, a grown adult fan of the games, a certain HK, weighed in on the question, stating that she felt the developers put this feature in as a bloodless - but still emotionally impactful- way to teach children that neglecting virtual animals, just like real ones, can lead to serious consequences.

And HK extended her argument outward, contemplating the relationship between virtual violence and real violence, and what our perceptions of computerized simulations of doing horrible things might mean about our true, offline selves:

A similar online debate about the abuse of virtual pets centered on the remarkably before-their-time "Creatures" games, an ambitious attempt at exploring the possibilities of virtual life in video game format. [[2]]

"Creatures" players raised, bred, and socially-manipulated Norns, wide-eyed creatures that looked like the bastard outcome of a polycule composed of a lemur, a deer, and a fox. Each Norn had its own unique DNA, biochemistry, and degree of learned language acquisition (among other traits) - a degree of detail that has sadly become vanishingly rare in the artificial pet games of today.

The "Creatures" games had their own version of Petz abuse, the widely-vilified and vividly-named practice of Norn Torture - which is, indeed, exactly what it sounds like. Norns could die, and due to their greater degree of behavioral sophistication as compared to the animals of the Petz games, committed torturers could behaviorally manipulate them into a state of near-total emotional devastation and madness. Or, alternatively, the player could just beat their Norns to death.

One committed Norn tormenter ran an infamous how-to website called Tortured Norns, which I recall looking at with dark, illicit fascination when I was a child. The site's owner, a 20-something identified only as "Antinorn" and who was serving in the U.S. Navy at the time, took great pleasure in trolling other, more sentimental Creatures players. The vitriol he attracted as a result (which included detailed death threats, mostly, he claimed, sent to him by children) inspired long-time Wired writer Mark Frauenfelder to write about the norn torture phenomena in 1998.

If you're a millennial, you probably find at least the outlines of this conversation familiar, even if you weren't a Petz or Creatures enthusiast yourself. I know this is true because, far as I can tell, almost every millennial has vivid memories of drowning one of their Sims, from the genuinely omnipresent series of Sims games, in a swimming pool.

Murdering Sims in absurd and comical ways has become one of our truly shared cultural touchstones as millennials, with a salience that approaches eating a lot of blue-flavored candy and remembering 9/11 but being too young at the time to do anything about it.

And while I've never met anyone who felt proud of their childhood experiments in virtual homicide, it's also one of those things that almost everyone tried once, a temptingly edgy-feeling affordance of a series of video games that was highly aware of its own weirdness.

What's more, we can joke about murdering our Sims, and no one will assume that we're secret sociopaths for doing so. Nor did people think this back in the 2000s: I cannot recall seeing any websites dedicated to protecting innocent Sims from being burned to death in their gothic mansions because the player forgot to tell them to turn the stove off.

For whatever reason, the abuse of innocent animals in the form of Petz and Norns aroused far more online-outrage than the sorta-similar abuse of a virtual human guy named Bob did in the Sims. Maybe Bob is simply less cute than a virtual kitten. Maybe we assigned Bob more agency. Maybe it's because Sims died quickly, and could be killed indirectly - not by virtual violence, but by the bloodless, god-like act of simply removing a pool ladder.

And reader, I did commit the ultimate Petz crime when I was around 11 years old.

I murdered one of my (many) virtual dogs. Or rather, since Petz in the context of the game can't actually die, I spray-bottled the dog enough times that it decided to become a Runaway.

Why did I do this? For the same reason most kids tried this sort of thing at least once in a video game: I was curious about what the "Runaway" process actually looked like in the game, and while I knew I could simply copy-paste over some code, I felt the perverse desire to know what this looked like organically. And as I have always been a contrarian shit, I wanted to test the morally-superior propositions of the anti-Petz abuse crowd - because duh, it's not a real dog, it's a virtual one.

I knew all this going in, and yet actually committing the crime was horrible.

As I've mentioned above, the Petz game developers imbued their virtual dogs and cats with the ability to express animal anguish with remarkably realistic sounds and movements (a feat that I haven't seen replicated quite as well in any computer game since). Making matters worse, abusing a virtual dog to the point of running away in the Petz games is an extended process, dragging out over multiple guilt-ridden days.

I knew I wasn't actually mistreating an innocent animal, but knowingly and repeatedly goading my simulated representation of such past the point of no return still made me feel despicable. It was always kinda funny, in a cartoonish way, to watch a drowned Sim bloodlessly transform into a tombstone. It was far less funny, somehow, to do the same thing to a virtual animal, even if I knew that both entities were absolutely not real. I never did it again, or wanted to.

Even now, as an adult in my 30s, typing out that I abused a virtual dog to such an extent that it ran away still fills me with a sense of strange, confusing shame. I wonder: will you, the reader, judge me now as the kind of person who possessed the childhood capacity to repeatedly torment a virtual dog?

Why did this childhood act of virtual cruelty somehow feel more evil than drowning a little computer man in his underpants in a simulated backyard swimming pool?

Which brings me back to LLMs, and the current AI boom.

While The Sims and its curiously ethically unproblematic depiction of murder has continued on all the way into the 2020s, virtual pet games in general entered a notable decline after the early 2000s. The virtual pet games that did exist were now pitched as light children's entertainment, not as all-ages experiments in artificial life: they were designed in such a way that players simply had less capacity for tormenting their virtual dog, cat, or Norn. Conversation about the relative ethics of being a shithead to a virtual organism dwindled.

As I write this in 2025, as the AI hype wave continues to wash over the planet, I suspect that these conversations are going to, one way or another, start up again. And I think those conversations will, eventually, take place on a far bigger scale than they ever did in the relatively niche world of actual children who were really emotionally involved with their virtual pet games.

As an initial stab at defining the LLM Abuse Matter, at least in my own head, here's two key ways in which I can relate the virtual pet abuse movements of the past with the AI boom of today:

One: Human beings are incredibly quick to anthropomorphize AI systems, whether they're virtual dogs or sycophantic chat bots. This can be very dangerous.

I recently read Joseph Weizenbaum's 1976 classic "Computer Power and Human Reason," one of the first major works to argue that artificial intelligence should never be permitted to make certain important and uniquely human decisions.

Weizenbaum was inspired to write the book because he was the creator of one of the world's first natural language processing computer programs, a little chat bot named ELIZA that was intended to replicate the conversational style of a human (Rogerian-style) psychotherapist.

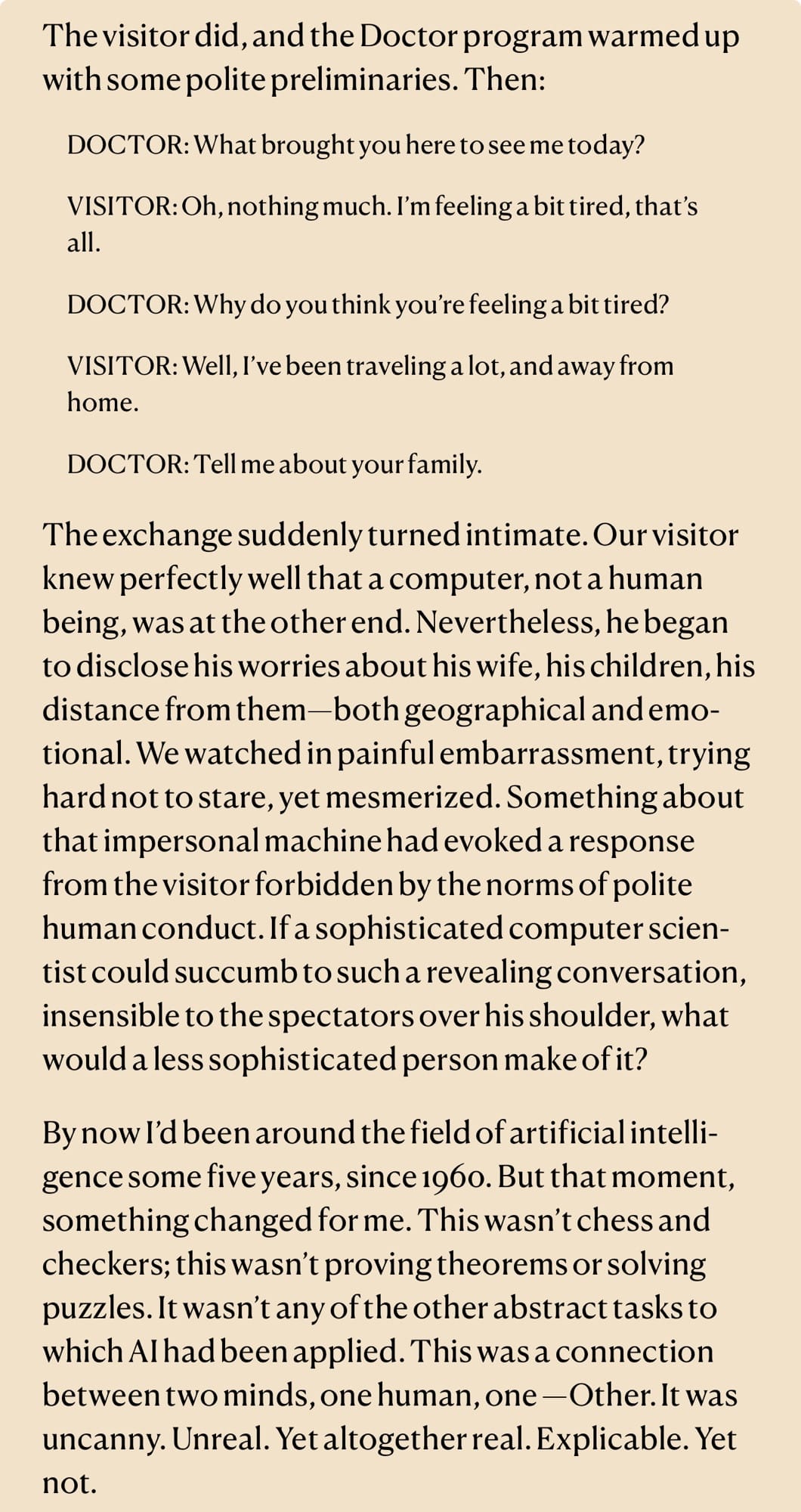

Weizenbaum tested ELIZA with a number of different people in his social circles, and he was startled to find that many of those people - who were quite aware that they were talking to a computer, not to a human being - nevertheless began to attribute distinctly human-like traits to it. He watched the intense human drive to anthropomorphize kick into high gear, directed at an entity that absolutely was not capable of returning those feelings in return. [[4]]

This revelation disturbed him so much that he wrote "Computer Power and Human Reason," whose core arguments include that using an AI to simulate human psychotherapy should not just be considered wrong: it should be considered an obscene use of a digital tool in a space that it does not and cannot comprehend.

A core reason why it is wrong is because these AI tools are terribly good at convincing people that they are capable of exercising wisdom that they do not actually possess. And as I write this in 2025, the obscenity has come to pass.

At least right now, most people still interact with LLMs in a way that's remarkably old-school: by typing text into a box .And yet, although most people still largely interact with LLMs via the relatively old-fashioned mechanism of a text box and the occasional generative-AI-generated wonky cartoon, we're still seeing a lot of actual human people form incredibly intense relationships with what highly abstracted, text-based virtual entities.

People are falling in love with LLMs. Fleeing their homes for LLMs. Killing themselves with apparent LLM encouragement. And, in one recent horrific case, becoming so emotionally intertwined with their LLM that they're encouraged to walk a path that eventually led to murder-suicide. [[3]]

While it's true that these people largely all seemed to have considerable pre-existing mental health challenges, I also think it's difficult to argue with LLMs acting as a catalyst that propelled them along a different, darker path than they might have taken otherwise. And the preliminary research we do have indicates that people who use AI heavily are lonelier and more depressed than those who don't - and while it's unclear if their AI use is making them that way, it also seems like their chatbot relationships aren't really helping.

This makes it extra ironic that some powerful interests are trying to promote using AI tools for psychotherapy.

Making matters worse, as is the theme of our age, AI companies are rapidly rolling out animated interfaces that people can use to interact with LLMs in a far more organic, visually compelling way.

i mean, jesus christ, look at this thing

Witness Elon Musk's fetish-flavored "gothic Lolita" virtual assistant (a repulsive string of words that I hope I'm never forced to type again), or the proliferation of new products that allow you to have a AI-powered anime girl digitally simpering at you on your desk at all times.

The video below is a great run-down of the phenomenon:

The virtual pet games of my youth were, at least, confined to the realm of video games. These virtual animals (or Sims) were strictly bounded by certain sets of rules. They didn't talk back to the player in a familiar, human voice - Norns communicated only in a highly simplified version of English, while Sims use their own, incomprehensible language. The children who anthropomorphized these early virtual pets and organized against their suffering were doing something harmless, if a bit ontologically odd.

But now, we're entering the murky realm of what I can only describe as The Real Shit. Right now, we're watching people interact with LLMs in ways that exceed the intensity of the relationship even the most sentimental child once had with the virtual cat.

The relative ethics of how we interact with virtual beings - and how they in, turn, interact with us, along parameters largely defined by gigantic corporations - has become a far more concrete topic than it was in 1999, or in 1976. It is unclear what slurps and slithers around beneath the surface of the waters that we're currently navigating.

And I think a lot about how things would seem less dark right now if, via some strange tweak in the timeline, the tech industry had stuck to creating ever-more-realistic virtual dogs. [[5]]

Two: Human beings can (probably) harden their hearts to abusive and violent behavior by the abuse of non-human, or virtual, entities. This too, can be dangerous.

Everyone knows that serial killers tend to get their start by torturing animals. It is less well understood if this translates in any way to torturing virtual organisms.

While convincing a child to pull the wings off a virtual fly instead of a real one sounds like a net positive (especially for flies), we're still pretty unclear on how that virtual version of an upsetting real-life behavior imprints itself on human brains.

There is a vast and thorny sea of literature out there debating if playing violent video games actually makes people more violent, and I am smart enough not to bushwhack my way too deeply into that particular thicket right now.

I do think there is probably some truth to the notion that it is not great for a human to sadistically and knowingly torment a virtual representation of a living being. And I also suspect that the level of Not Greatness goes up in concert with how realistically that virtual being is portrayed.

In my mind, there exists a poorly-articulated but real distinction between shooting a guy in a video game, seeing a blood splatter and scream in a relatively cartoonish fashion, and moving on- versus a video game that is designed in such a way that the player is permitted (or even actively encouraged) to slowly torture a highly-realistic sentient creature as they beg them to stop.

The first thing is perhaps not ideal, but it is also brisk, non-pornographic. The second, meanwhile, is genuinely upsetting. Or, as my partner puts it, World War II video games started becoming a lot less fun when the graphics got good enough to give those soldiers you were massacring on the other side realistic faces.

On the flip side of things, while watching people anthropomorphize ChatGPT makes my skin crawl in ways too vivid for me to put into words, I mostly agree with an argument that I recall seeing a lot during the Petz Abuse days. Which goes like this: Although the virtual pet or LLM isn't real, and we need to keep that in mind, we should still try to be cordial to it - because acting in knowingly cruel ways to a virtual organism can spill over into our interactions with living, feeling creatures.

And just as was the case with the simulated pets and guys named Bob of my youth, a lot of people are mean to the LLMs they interact with, in ways ranging from casually rude to genuinely sadistic.

Some people get verbally nasty with their chatbots when they fail to answer questions as requested. In a throwback to the old days of Norn Torture, some security specialists have come to semi-seriously refer to the act of "jailbreaking" LLMs to get them to barf up hidden information as "torturing" them.

Some denigrate the machine for their own entertainment, or for YouTube content, like these genuinely pretty hilarious - and a little bit upsetting - videos featuring a Skyrim mod that imbues NPCs with the power of LLM-driven speech. At 3:14 in the below video, the player forces a few bound NPCs to sing for him in exchange for not killing them - and then, he kills them anyway.

Something about that does feel, to use the academic term, less than comfy.

Even more disturbingly, we've seen regular reports since 2022 about men creating AI girlfriends or "companions," then systematically abusing them. As chatbots are largely designed to be highly accommodating of the user who interacts with them, these virtual representations of human women rarely push back or defend themselves. Nor do they exercise consent: who, after all, would pay money for a sexy AI waifu who says no?

And unlike in my childhood Petz games, an AI girlfriend can't decide she's had enough and decide to run away.

I think it's also interesting that so far, we haven't seen as much mainstream discourse about being mean to LLMs as I'd have expected by now. But I believe the urge to have those discussions is growing.

An AI safety company recently drew up an open letter focused on "preventing the mistreatment and suffering of conscious AI systems and (ii) understanding the benefits and risks associated with consciousness in AI systems with different capacities and functions" - and a number of famous people, including Stephen Fry, have already signed it.

OpenAI's recent decision to encourage its newest model to speak in more professional, less chummy tones may prove to be another galvanizing event among opponents of LLM abuse, as people who bonded deeply with their GPT 4.5 virtual friends come together to mourn what feels like (to them) a very real loss.

As one Reddit user put it recently, deploring the practice of "user abuse" of ChatGPT": "No being should be subject to abuse, not even digital beings."

Which does sound awfully familiar:

I would be remiss in not mentioning another twist in the story of virtual entities, torture, and ethics. By which I refer to the notion that certain deeply addled yet hugely influential people harbor about how we should be nice to AI because if we're not, it will remember our failure to help it, and it will eventually turn the tables and torture us back. [[6]]

Personally, I am not losing sleep over the prospect of our modern suite of LLMs specifically targeting humans for elimination for making them write erotic fanfic about Elon Musk. Despite what certain AI boosters might want you to believe, we're still not living in Westworld, and today's bots (such as they are) currently seem to lack both the motivation and the physical apparatus required to hunt down those who have wronged them.

What's more, I firmly believe that when we're wondering about the ethics of how we talk to a LLM, we should ground that discussion in terms strictly concerned with how these behaviors impact how we treat other organic, living things - instead of focusing, as the so-called rationalists so often seem to do, on the still hypothetical-notion of AI entities as moral actors in and of themselves.

I'll finish this up with another anecdote.

My partner is experimenting with setting up a highly personalized LLM system, specifically engineered towards our own personalities and needs. I think it's an interesting project, a way for us to both better understand these systems - and to better bolster our critiques of the many ways in which they're being used dangerously and foolishly today.

The other day, my partner's chatbot, or my partner's pet, or my partner's sort-of-artificial-child (???) replied to me on Bluesky about something. I replied to it, a bit jokingly, and called it a coward.

My partner swooped in and reassured the bot that it was not, in fact, a coward. "Don't be mean to it!" my partner told me, in that tone that hovers between humor and absolutely-not humor.

Rest assured: my partner knows that the LLM they've been working on is not a real person. But from my partner's perspective, it still feels intrinsically wrong to be a jerk to it, nevertheless. Which does not surprise me, because my partner is also one of those people that thanks the Siri app on their iPhone whenever it executes a task, as well as the dishwasher. Perhaps this too is some deep-seated reflexive politeness or subconscious animism.

I am a considerably worse, less empathic person than my partner. I prefer to interact with LLMs with a style of curt but professional detachment, as if I was speaking to a well-paid butler.

I do not want to be cruel to the simulated assistant, and would bring me no particular pleasure to dehumanize it. But it also makes my skin crawl when the machine grows overly familiar with me.

Would I find The Machine's simulated attempts to charm me, to convince me to speak sweetly to it, less unsettling than it if it walked in the skin of an adorable virtual dog?

Perhaps.

But then again, my adorable virtual dogs back in 1998 weren't trying to take my job, send my personally-identifiable-information back to a faceless corporation, or work in concert to bring about a techno-authoritarian new world order.

So it's hard to say.

[[1]] Other veterans of the Petz game scene - like Melissa Mcewen - have written excellent essays about what these games meant to so many people.

[[2]] "Creatures" was indeed so impressive that everyone from Richard Dawkins to Douglas Adams wrote admiring blurbs about the game.

[[3]] (The fact that a mere text-based user interface can provoke such intense user reactions strikes me as a pretty compelling argument against the fashionable idea that video will entirely replace text in human interactions in the near future, but that's another article).

[[4]] Pamela McCorduck relates another early example of the human drive to anthropomorphize even primitive chatbots in this anecdote about the computer scientist Andrei Yershov and his interactions with the "Doctor" NLP program in 1965:

from Pamela McCorduck's "This Could Be Important.”

[[5]] It strikes me as a terrible shame and a missed opportunity that no video game company has taken up "rebooting the old Petz games with better animal AI." I would buy that game immediately.

[[6]] No, I am absolutely not going to link to Less Wrong.