Trump's Attempted Assassin Flew A Drone Over the Rally Site: My Thoughts

It was Friday evening. I was trying to relax.

And then all of a sudden, a dozen people sent me the same link.

Drone news. Of course. Why does big-drone related news never seem to drop at 10:00 AM on a Tuesday?

Anyway, I will briefly sketch my thoughts on the Thomas Crooks - Donald Trump Attempted Assassination Drone Incident of 2024.

Per local law enforcement authorities quoted in a Wall Street Journal piece, Thomas Matthew Crooks - the 20-year-old of muddled political leanings who attempted to assassinate Donald Trump - had been able to fly a drone over the site of the ill-fated rally on July 13th, a few hours before it began.

The drone, which NBC claims was a DJI drone (which seems likely, as they're by far the most popular US drone brand), was recovered from Crooks car.

Per the reporting, authorities claimed that Crooks had flown an automated route over the site, which sounds to me like a description of one of the various apps that permit DJI drones to navigate by pre-set waypoints. The app could be Litchi, could be DroneLink, could be one of a number of other possibilities. It's hard to say with the available information.

In no particular order, then, keeping in mind that we have limited information at our disposal:

Why did Crooks bother with flying a drone over the rally?

For over a decade now, I've been filled with frustration and rage over how so many people fixate on how drones can be used to move stuff around, while paying far too little attention to what drones are actually really good at: collecting information.

Drones are truly revolutionary tools for allowing pretty much anybody to collect highly detailed aerial information about the world at a very low cost, a capability that used to be restricted to a very small number of people who had the ability (and the cash) to access aircraft or satellite data. This has led to a lot of wonderful things for humanity, benefiting disaster responders, scientists, farmers, construction workers, filmmakers, and many, many more.

Of course, there's a flip side: weirdos with guns can use drones to collect information too. Enter Thomas Crooks.

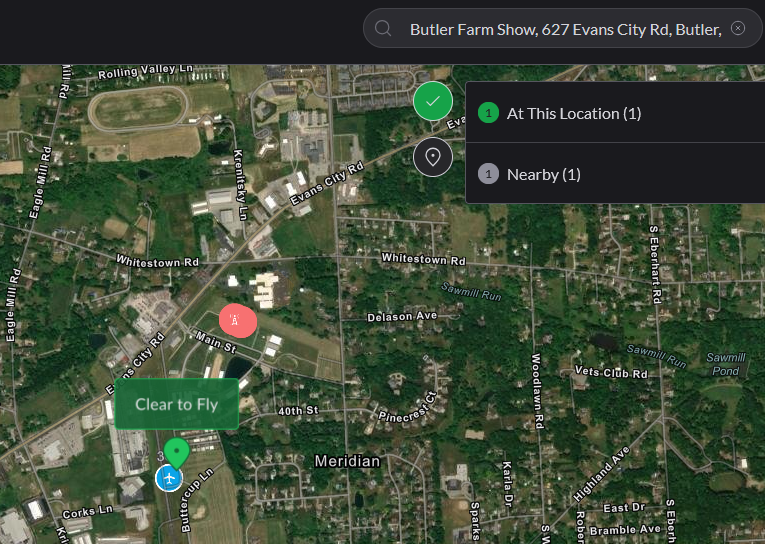

If I were to wildly theorize, I'm guessing that Crooks looked at satellite imagery of the event from Google Maps and the like, realized it wasn't going to be entirely up to date, and decided that he'd check and see if he could get away with flying a drone over the site of the Butler Farm Grounds to collect super-recent information on the setup.

Crooks may have been pleasantly surprised to find out that nobody noticed, and nobody stopped him.

Whoops.

We know that he was able to collect the information, which leads us to a second question, a question that far too few people who comment on drones and security pay attention to: what did he actually do with that data, and how useful was it, as opposed to what he could get on Google Maps?

It'll be hard to say for sure, because the shooter is dead, but I can see a few advantages to his being able to add a total aerial view to his on the ground scope-out of the site. I imagine it was handy for him to be able to compare older Google Maps satellite imagery of the roof he decided to fire from with brand-new data from the day of the attack.

However, I'd also be surprised if, in this case, the data proved to be decisive - considering that it appears he was able to easily physically access and walk around the site on the day of the rally, too.

Gee, someone should really fund research into how drone-collected data can be used in real-world situations by bad actors. That would be cool.

As many have noted, including Ted Cruz (whose existence I'm mad about being forced to acknowledge again), it is interesting that the Secret Service did not use drones to monitor the Trump rally before it began.

The Secret Service does have a drone program, and they've reportedly been at least experimenting with drones since way back in in 2015.

It's unclear why the Secret Service didn't use drones at the Trump rally. Lack of resources? Struggles with de-conflicting airspace (which can be a real struggle)? Simply didn't think it was necessary? It's hard to say at this time.

The Secret Service also didn't ask for a Special Government Interest drone flight waiver for the Trump rally, according to an FAA spokesperson quoted in Newsweek.

Here's a bit more on the Secret Service and small drones.

May 2020, the Secret Service claimed it would begin "evaluation of small surveillance drones" with the goal of launching a full program in 2022. It also released a Privacy Impact Assessment concerning the nascent drone program at the time.

The Secret Service published an update to this PIA in September 2023, which describes agent's efforts to minimize collecting sensitive information about individuals on the ground. Presumably, this PIA means that the drone program was in fact launched in 2022. The new text also notes that the Secret Service intends to use drones not just to support its protective mission, but also its investigative mission.

Also interestingly, despite much public US government suspicion of DJI drones and how they might be exploited by the Chinese government, the Secret Service reportedly was buying DJI drones as recently as 2021, as reported in Axios. Per contract records reported in this Forbes piece, the Secret Service has spent at least $400,000 on drones.

It's unclear what specific drones the US Secret Service is using today, although a January 2022 press release from Darley/Parrot claims that the US Department of Homeland Security had awarded them a $90 million five year blanket purchase agreement to themselves and four other companies that produce Department of Defense-approved drones.

The Forbes Piece also notes that Secret Service spent $70K on drones from Axon (the folks who makes Tasers), as well as $200,000 on drones from military equipment suppliers Atlantic Diving Supply and Paladin Defense Services.

Both vendors stock a number of military drone solutions from a number of different companies, although it's interesting that none of them appear to be on the current Department of Defense-cleared Blue UAS list. Axon's drone solution isn't on that list yet, either.

As for the local Butler Township police, it's unclear if they have drones - apparently, they don't even have a police chief at the moment. But they were at least thinking about getting drones in 2022, like most red-blooded US police departments today.

The Secret Service didn't ask for temporary flight restrictions over the Trump event.

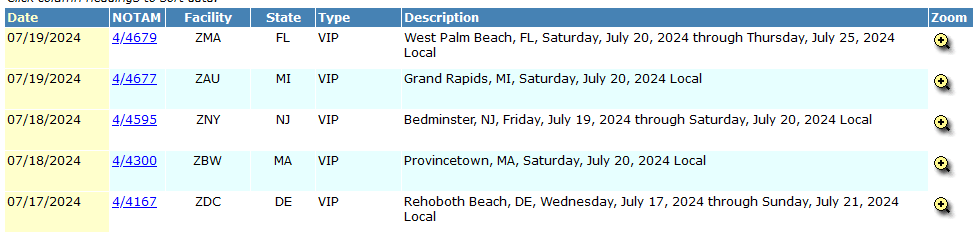

The Secret Service has the capacity to coordinate with the FAA to temporarily restrict all air traffic over certain areas for special events or the movement of protected individuals, a rule that includes drones. It appears that nobody asked for a VIP-focused Temporary Flight Restriction (TFR) over the July 13th Trump rally.

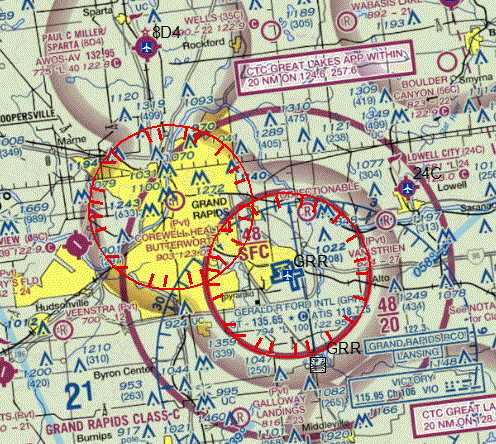

While the rally took place near a small airport, the airport appears to be small and located in uncontrolled airspace, meaning that drone flight is permitted there under normal conditions.

However, it appears that the Secret Service is making up for lost time. I just checked, and VIP TFRs have been recently issued for today's Trump rally in Grand Rapids, Michigan, as well as for areas over Trump's property in Bedminster NJ, and over West Palm Beach - the vicinity of Mar-A-Lago.

Popular consumer drone makers, like DJI, have technology in place that restricts drone use in TFR areas, up to the point of forcing automatic landings if one is suddenly issued when the drone already is in the air. However, there are ways to get around these, if someone is sufficiently motivated.

Despite these restrictions, 2022 testimony from Samantha Vinograd, Assistant Secretary (Acting) for Counterterrorism, Threat Prevention, & Law Enforcement Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans at the Department of Homeland Security claimed that the Secret Service had, since 2018 "encountered hundreds of drones violating temporary flight restrictions that protect the President and others."

Where were the counter-drone tools at the Trump rally?

Counter-UAS (umanned aerial systems) technology has been a major government and police obsession in the US since 2019, and many state governments, local governments, and police forces have access to it.

While attempting to describe the full scope of counter-UAS technologies would be beyond both the scope of this piece and my own patience on a lovely Saturday in July, rest assured that there's a LOT of vendors selling a LOT of different methodologies for detecting suspicious drones in the air, of variable effectiveness. The main point is that they do exist, and it's surprising that nobody seemed to be using them at the Trump rally.

The Secret Service says it has an Counter Unmanned Aerial Systems team that "develops and implements unmanned aerial systems detection and mitigation plans for sites visited by the president and vice president of the United States, National Special Security Events and other designated major events."

In August 2023, the Secret Service announced that it was looking to hire CUAS specialists to operate "a variety of fixed, mobile, portable, and other C-UAS sensor systems, to detect, identify, track, and mitigate a threat UAS and/or the UAS operator," among other tasks.

Interestingly, the Secret Service's 2023 and 2024 public budgets both included the same dollar amount for CUAS: a very, very modest $5,270. CUAS technology tends to be expensive, and I'm now very curious about what that rather tiny amount of money is being spent on. I imagine someone who has actually paid for access to those government website contract-lookup sites, unlike myself, could dig more up. (Hit me up if you do).

The US Department of Homeland Security does have a much heftier CUAS program, which has been budgeted $26.2 million for FY 2025. Maybe they share resources with the Secret Service.

DJI Drones Do Broadcast Remote ID Information

If Thomas Crooks was flying a DJI drone, it was probably broadcasting Remote ID information, which is a feature that's built into most recent DJI models (and is activated via firmware updates). DJI has done this to comply with the US Federal Aviation Administration's Remote ID rule (Part 89), which was finalized in early 2021, and took full effect in March 2024.

Remote ID functions essentially like a digital drone license plate, and the idea is that both the general public and law enforcement can use tools to pick up on these signals and track them back to the drone operator.

However, local police and the Secret Service would only have been able to nab Crooks with this method if they were actively monitoring Remote ID signals when Crooks flight actually took place, a few hours before the rally (and no one seems to have reported on the exact number of hours).

Maybe this incident will lead to more discussions about just how far in advance one should be setting up counter-UAS interdiction and detection measures before an event.

It is possible to shut off remote ID broadcast from a DJI drone, and there's information circulating around the Internet about how to do this (and no, I'm not going to link to it, nice try).

Combatants using DJI drones in Ukraine and Russia, among other places, pretty much always use certain methods that shall go nameless to turn off remote ID, as the signal can give away their location to the enemy. Far as I'm aware, we currently have no idea if Crooks actually did disable remote ID on his DJI drone or not.

But I would certainly like to find out if he did. That would tell us a lot about his level of sophistication, drone-wise.

What Happens Next?

While I hate predicting the future, because everyone gets mad at you when you get it wrong, here's a few things I suspect - or worry, or hope - will happen as a result of this.

Yet more scrutiny on DJI drones. Great. Cool!

I'm a DJI moderate: I believe that the members of the US government doing sensitive things, and other people doing sensitive things (including US police) should NOT be using them. I also think that most civilian drone users, who are not doing sensitive things - including people like government-employed wild ferret researchers - should be allowed to use them.

And that's why I'm very upset about current Congressional efforts to ban DJI drones for all American drone users, which I think is a gigantic overreaction to the actual risk, and will shank the currently thriving civilian drone data services industry. Which is also the one I work in. Like it or not, DJI is the world's biggest drone maker, who make affordable, useful drones that average people can afford - unlike the DOD-approved US and European drone makers who make extremely expensive drones tailor-made to the needs of police.

In this case, the fact that the drone was made by DJI had very little to do with the actual incident, other than the fact that they make widely available cheap drones that anybody can use, including wackos with guns. I continue to firmly believe that the benefits of allowing the public to use cheap drones (with reasonable restrictions) outweigh the security downsides of wackos being able to use them.

I also think it's quite possible that if the Secret Service and local police had issued a TFR (temporary flight restriction) over the area, and had started monitoring the area for drone activity at the start of the day, someone would have caught Crooks and avoided this entire mess.

Better Conversations About The Security Relevance of Drone Data...hopefully.

As I mentioned earlier, too many people focus on the dangers of "explosive drones flying into stuff." This mindset ignores what drones are mostly used for, by both bad and good actors, today: collecting information about stuff.

I have long been dreaming of getting research funding to dig into a very big, tragically under-investigated question: "OK, so how can people actually use drone-collected data to create harm? What could bad actors actually do with that data, in practice?"

While this may seem like a real "duh" question, it's more complex than it seems.

While I can come up with a number of qualitative, hand-wavey answers to it, there's very little data in the literature out there that attempts to methodologically connect "somebody got their hands on some data collected by a small drone" to "this information enabled them to execute XYZ horrible act."

I firmly believe we CAN prove these links.

We just need some researchers to actually do it. Obviously, I'd like to be one of these researchers. But I'd generally like people to really start thinking about these questions, and to start better understanding how drone data can be used to harm others in practice.

Discussing Barriers to Broader Drone Use for Security at Public Events.

The Trump assassination attempt has really highlighted that while there's a lot of talk about pervasive drone deployment at public events, there's fewer instances where people actually do it. This could lead to some interesting conversations about why they aren't being used as often in practice as a lot of past reporting and government press released might lead you to believe.

What are the impediments here? I'd like to know.

And of course, what are the impacts on public privacy and free speech rights if drones DO become more ubiquitous?