Visiting Crete: Archaeology, Food, and Raki

Crete is big, weird, and magnificent - a lengthy, arid slash of an island that humans have been occupying, conquering, and visiting since at least 7000 BCE, with a highly distinctive culture that is somehow both very Greek and highly unique to itself. While the mysterious and aesthetically-gifted Bronze-Age culture of the Minoans gets the most press, Crete has also been home to a dizzying array of other cultural traditions, from the ancient Greeks and Romans, to the Arabs, the Venetians, and the Ottoman Empire - and I'm probably missing a few.

It's also been the site of many famous wars and rebellions, as the people of Crete ferociously battled throughout the 1800s become independent from the Ottomans and to join the rest of newly-independent Greece - a fight they'd take up again in World War II, as the Cretan resistance drew blood from the Nazis during their years of occupation. Crete's distinctive culture gave us famous authors like Nikos Kazantzakis, the author of "Zorba the Greek," the legendary Renaissance artist El Greco, and a profusion of passionately-protected culinary traditions, which range from goat cheese-making to baking delicious pastries to unlicensed raki production way up in the hills.

This remarkable diversity of perspectives, histories, and cuisines makes modern-day Crete one of the most culturally interesting places I've visited in Europe, with something to offer pretty much every traveler with a pulse. And while Crete is extremely popular (and crowded) in summer, if you visit in spring, like I did, you'll likely encounter excellent weather, low prices, and a lot of solitude.

This is going to be long. Scroll to the end for restaurant suggestions.

General Crete Advice

You need to rent a car. Crete is, sadly, not a place blessed with excellent public transit. While you can visit without a car, you'll be restricted to a very small part of the island, and will miss out on many interesting things. If it's at all possible, I suggest you rent a car (if you're not on a package trip that includes a driver) - and look, I'm a notoriously wimpy driver, and even I did it. And I thought the freedom of exploration was worth the stress.

There's a bajillion rental car companies: I used Eurodollar and they were a perfectly solid choice for renting an affordable automatic-transmission (my brain does not cooperate with manual). Bring your own car-holder for your phone for navigation purposes, because you are absolutely going to want to use your phone GPS.

But don't unthinkingly TRUST Google Maps, either: consider the situation before you turn off onto a supposed shortcut, because those are often unpaved roads filled with boulders through endless goat fields.

Ensure that where you're staying has parking, especially if you're in a place with lots of charming pre-industrial-age winding streets like Chania. Be prepared for some harrowing parallel street parking experiences if not.

Dropping off your car is also an informal affair with some Crete rental agencies, if you're doing it very early or late: I drove up at 7:30 AM, dropped my keys in a lock-box, and off I went across the street and into the airport. Nobody has sent me an angry letter yet, so I guess that's what I was supposed to do?

Driving is interesting, but manageable. Cretans have a few local driving customs, which I do not endorse but you'll have to live with anyway. Primarily, if a Cretan wants to pass you on one of the island's many, many two-lane highways, they will expect you to drive as close to the shoulder as feasibly possible so they can do so. If you don't do this, they will firmly insert their headlights up your ass (mostly metaphorically) until you comply, or until you come to an area with two lanes, allowing them to huffily pass you.

This will come up often, because locals all seem to drive at least 20 miles above the actual speed limit. Except for the ones who drive 20 miles below it. Other tips: lanes are more polite suggestions than rules, parking is largely based on vibes and raw animal cunning, and keep an eye out for goats and dogs in the road. While this may sound viscerally upsetting, I assure you again that I am a big-time driving coward and I still managed it.

Crete is very safe (other than driving, and acts of stupidity in nature). Beyond the invigorating experience of driving, Crete is a very safe place for tourists, with low crime rates and zero worrisome local wildlife, if we exclude angry goats and nude Germans. While I made sure to keep my car locked and belongings out of sight, I didn't hear any warnings about car break-ins, which makes me think they're not common. Tourists do get in trouble by doing things like underestimating Crete's rugged terrain, hot weather, and the cruel indifference of its ocean. Budget appropriate time for things like hiking in gorges, assess your fitness level, and bring lots of water.

It's HOT - and crowded in summer. Crete gets stupid hot in summer, and summer basically starts in mid-May. And although it's a dry heat, it's still hot enough to seriously harm you. Bring water, sunscreen, and basic common sense about when it's best to stay in the shade.

Despite the heat, tourists flock to Crete in summer, rendering places that I found charmingly quiet into heaving pits of sweaty human irritation (or so I am told). If I were you, I'd visit any other time.

Multiple locals congratulated me on my choice to visit in the first part of May, and the weather was very nice, other than a few days of rain and sand-blasting winds over my two and a half week stay. The water was still a bit too cold for my taste in May, but people who aren't complete wimps would probably be fine.

Gorges in Crete are usually closed from around the end of October until early May. I didn't do any gorge hikes during this trip as I was traveling alone, it was still early in the season, and didn't want to deal with the logistics. I absolutely will in the future, though - I want to visit the irresistibly-named Lassithi Gorge of The Dead in Zakros.

Archaeological Sites: Bothering the Ancient World

Mostly, I travel to see archaeological sites. If there's an obscure historical site where something vaguely interesting happened at some point in the distant past, I'll find a way to get out there and look at it. Nothing in this fallen world gives me more joy than poking around quiet ruins, especially if there's pot-shards lying on the ground. (Look at them, but don't touch them, and do NOT take them home with you).

If you also harbor this particular archeology tourism perversion, you're going to love Crete. Yes, everyone knows about the Minoan palace of Knossos, and it is worth going to, especially if you get there when it first opens before it becomes inundated with tourists. But everybody talks about Knossos.

I want to suggest some other archeological sites to you. They're places that you very well might mostly have to yourself, especially if you're traveling in the quieter times of the year, like I was.

Minoan Palace of Phaistos

The group of ancient Minoans who built Phaistos knew the importance of both strategic altitude and a sweet-ass view. They plonked their administrative center on top of a piney, wind-swept hill with a truly incredible view of the legendary Mt. Ida - the place where the Ancient Greeks believed that Rhea, Zeus's mother, hid her godly son in a cave so his deranged father wouldn't eat him. (You know, like in the Goya painting).

Today, Phaistos is a remarkably well-preserved Minoan site, as Minoan sites go - and in my opinion, it's more interesting than Knossos, and is far less likely to be crowded. Humans first moved into the Phaistos area around 3600 BCE, and proceeded to build the first in a series of "palaces" (which may have been more like administrative centers), which they'd rebuild three times due to recurring issues with earthquakes. Ancient Minoan palaces had convoluted and complex layouts, which may have been intentional for security reasons. Indeed, the famous legend of the Minotaur and the labyrinth may have come from a mythological mash-up of the Minoans fondness for both bulls and extremely confusing interior design.

We don't know much about how ancient Minoans lived their lives, as no one has figured out how to read their alphabet yet. Indeed, that's what makes Phaistos famous: the legendary Phaistos Disc was found at this place during excavations in 1908, a strange object covered in spiraling probably-alphabetical marks that the world's finest palaeographers have yet to crack. You can see it at the highly impressive Heraklion Museum, and yes, like most wonders of the world, it's smaller than you'd expect.

We do have a few guesses about how the Minoans went about their lives. They seemed to worship goddesses, and there's speculation that women played a much more active role in their culture than they did in the luridly-misogynistic world of the later Ancient Greeks. People had their own seals which they used as a kind of signature, decorated with a dizzying array of emblems, and athletes might have practiced catapulting themselves over bulls for both recreation and for religion.

As for what you can see on the ground at Phaistos? Like most Minoan palaces, the ruins have been (controversially) reconstructed to a certain extent, though not nearly as aggressively as was infamously done at Knossos. Here, you can contemplate ancient sunken chambers, which may have been used for purification rituals.

There are also impressive pavements and open areas, where Minoans might have had mass gatherings - they were a people who were big on collective feasting (like all civilized peoples), judging from the massive stew-pots that have been found at their sites.

Malia Palace

These well-preserved Minoan "palaces" are well-worth wandering around - and they're also right next to a very pleasant white-sand beach, about 45 minutes or so from Heraklion.

Abandoned at the end of the Bronze Age, the ruins are preserved by architecturally-interesting roofs, which bathe the path in an ambient orange light.

From the main unpaved parking area at Potamos Beach, or from the parking area at Malia Palace, you can walk along the shore a bit to the fenced-in ruins of the Minoan necropolis of Chryssolakkos, which translates into "pit of gold." It's a pleasant stroll along a dramatic coastal shoreline, and it's interesting to see the un-excavated and collapsed stone remains of ancient structures scattering the landscape. There is also a coastal hut along the shore near here that may or may not be occupied by a hermit - it is hard to say.

While digging here, archeologists found a now-legendary piece of golden Minoan jewelry, crafted into the shape of two bees:

I wandered up the parched and recently partially-burned hill that overlooks Chryssolakkos for a bit, and found a number of pot shards and other ceramic remains lying in the sand. (Look and don't touch if you find these).

Walking along Potamos Beach, you'll find interesting naturally-carved potholes in the volcanic rock, which often contain ocean creatures if the tide is in your favor. There are also rock-cut channels on the shore that appear to have been made by human beings, although I've been unable to find any information one way or the other about how old these cuts actually are.

A centuries old amphora (though not ancient) has been left on Potamos beach to add to the visual effect.

If you're hungry by the beach, Taverna Kalyva is a family-run Cretan seafood joint that does nice things with fried squid. It's right by the unpaved area where most people park.

Ancient Gortnya

Strategically situated in Crete's most fertile farming area, Gortnya, or Gortyn, was a place of remarkably long-lived historical importance, recognized since at least the time of the ancient Minoans, and deemed worthy of call-outs in both the Iliad and the Odyssey. Allegedly, it's the very place where poor Europa thought she was about to take a ride on a friendly white bull, and instead found herself kidnapped by Zeus, who'd been creeping on her in one of his various horny-animal disguises.

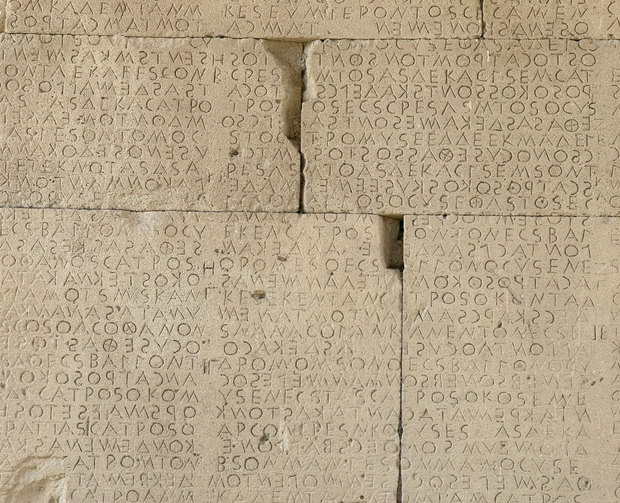

In 450 BCE, its citizens decided to write out their entire legal code onto a marble wall in the city agora, covering topics ranging from lawsuits, rape, the rights of divorced women (they actually had a few!), and property rights, among many others that have, doubtless, since been lost. This document is now Europe's oldest surviving legal inscription, and is a foundational text of the systems of laws we have today.

Gortyn continued to amble prosperously through history until 69-67 BC, when the city made the strategically wise choice to support the Roman general Quintus Caecilius Metellus in his campaign to conquer Crete. Augustus rewarded Gortyn for its perspicacity by making the place the capital of both Crete and Cyrene (today Libya) in 27 BCE. The city would grow to a population of as much as 300,00 during the Roman years, and would erect all the expected trappings of imperial urbanity, including baths, stadiums, a circus, theaters, temples (including one dedicated to Egyptian deities), and an impressive water-management system.

As Christianity began to take hold in Europe, Gortnya remained relatively populous in the late Roman and early Byzantine years - despite suffering destruction from one of Crete's perennial horrible earthquakes - hosting an archdiocese and a number of good-sized Christian monuments, including the 6th century AD Church of St. Titus, which you can still look at today. After yet another horrible earthquake hit in 670 CE, the site was abandoned.

Today, Gortnya is a truly sprawling and still-active archeological site, covering about 400 hectares - much of it still un-excavated, largely because there's so damn much of it. When you arrive, you'll see a parking lot and the gate for the paid, largely-excavated area, which contains sites like the aforementioned church, the tree where the Europa Incident supposedly took place, and the Law Code.

You should enter this area - and take advantage of the surprisingly nice cafe - but I'd suggest you then cross the street and spend some incredibly enjoyable hours wandering around the enormous, less-excavated side.

Pause for a moment to consider the site's famous 1600-year old olive tree and how it engulfs an ancient marble pillar, and something-something-Ozymandis. Then proceed into the scrublands beyond: you can't really get lost, and this is an ideal place for un-directed exploring.

When I was there, I criss-crossed crumbling ancient walls set among yellow grass and bright-red spring poppies, climbed up rubble mounds that contained brilliant-white chunks of long-forgotten marble statues, and had a ridiculous-looking hoopoe bird make weird noises at me from the safety of an ancient olive tree. Among the ruins, a herd of brown and black goats grazed on the spring grass and wildflowers, chivvied along by two local shepherds and a blessedly mild-mannered, small dog. No one else was around.

I walked around the fenced perimeter of the ongoing excavations, which includes the Temple of Apollo and sanctuaries to the Egyptian deities, as well as the remnants of other key municipal building - like the Praetorium, built during the future emperor Trajan's stint as the local governor.

For a while, I followed the pot-shard littered track of a maybe-Roman, maybe-Byzantine road that hugged closely to the side of Gortyn's old aqueducts, thinking pleasant thoughts about the people that had indisputably been walking along this exact road for at least a 1000 years.

I looked inside of an ancient statue niche, which might be Roman or might be Byzantine, and wondered about what people used to put in here, and who they were offering things to. This was the exact kind of thing I'd come all the way to Greece for.

After you've finished exploring the ruins, you should drive five minutes down the road to visit the excellent and very new Archeological Museum of Mesara, which contains many of Gortyna's most interesting artifacts, as well as a lot of other good stuff from the general vicinity. They don't allow pictures - but I was able to find this picture of the incredible crocodile-headed gutter they have at the museum, which should really incentivize you to go.

After all this historical entertainment, you're probably hungry, and for that, I suggest the nearby Platania Tavern in Ampelouzos, Greece - a friendly family-run place set in a lovely garden. Try the stuffed pepper.

Ancient Eleutherna

If walking alone through an ancient pine forest awash in the herbal scents of Greek springtime towards a monumental ancient Greek bridge sounds appealing to you, you should put Eleutherna very high on your list of Cretan destinations.

Eleutherna isn't very popular with tourists, but it is well known among archeologists thanks to a string of interesting 21st century discoveries in the ancient Greek (and then Roman, and then Byzantine) city's ruins. Set amidst a beautiful canyon, you can wander from the bottom of the ruins all the way up to the top along a series of quiet trails, set in a dramatic landscape of sheer rock, pine forests, and lush creek-watered vegetation.

You enter Eleutherna from the modern town on top of the canyon ridge: you can park here, in a rather tight parking area, or you can proceed down a steep road to the canyon's bottom and park at the Orthi Petra necropolis. Which is what I did.

Shaded by an elegant modern structure and criss-crossed by elevated boardwalks, Orthi Petra is a compelling glimpse into an ancient City of the Dead, just well-preserved enough to allow the viewer to properly imagine what it was like. Here, archeologists found a number of burials that helped them better understand the so-called Greek "dark ages," the period from 1200 to 800 BC during which people appear to have forgotten how to write using the Mycenaean Linear B script.

Among these finds was the funeral pyre of a deceased aristocratic warrior, who was cremated with another, headless man between 720 to 700 BC.. Researchers presume that the headless man, who was placed on the limits of the pyre, may have been a prisoner of war, executed to accompany the warrior into the afterlife. Many details of the burial hew remarkably closely to those described in the Iliad's account of the funeral pyre that Achilles built for his dead boyfriend, Patrocolus, upon which he placed the hacked-up bodies of Trojan prisoners of war. These similarities give us a clearer sense of just how accurately the Iliad described ancient Greek cultural practices: at least on this front, the story might not have been too far off.

In another tomb, archeologists found the remains of four women buried at the same time, accompanied by particularly impressive grave gifts. One woman was 72, while the others were younger: the current thinking is that these women may have been priestesses with an important, albeit little-understood, religious role in the society that they lived in. Scientists recently determined that another woman buried at Orthi Petra appears to have been a master ceramicist - the only woman known to have such a role in antiquity - due to patterns of muscle and bone development inscribed on her bones.

After walking through Orthi Petra, I decided to walk the half mile or so to another one of Eleutherna's ancient treasures: an ancient corbel bridge that likely dates back to Crete's Hellenistic period, and still stands today. With an occasional glance at my route in the AllTrails app, I walked along an unpaved path and found myself catching up with a group of goat herders moving in the other direction, and a shepherd gently throttling a young brown goat that had wandered off from the rest of the herd in the wrong direction.

He released the goat, we waved at each other (the goat just bleated), and I continued to follow the quiet course of a green and lushly forested creek along the canyon bottom, pausing to look at the occasional, crumbling remains of buildings that could well be anywhere from 3000 to 50 years old.

Maybe it didn't matter that much.

Eventually, the trail led me up a little rise away from the creek and to a metal gate, which was closed with a very loosely-wrapped wire. As every recent source I'd read indicated that the bridge was currently open, I optimistically concluded that this gate had to be meant for goats, and not for people blessed with opposable thumbs. So, I let myself in.

I headed back downwards towards the dried-out stream bed and the presumed location of the bridge - and I suddenly found myself in the sort of enchanted sacred grove I'd always visualized when I read ancient Greek myths about gods and nymphs drunkenly lurking in places unknowable by mortal man.

Ancient rock-cut early Christian tombs, including one that resembled a sort of low-rent hobbit hole with a modern coat of white-plaster and a glass-window, loomed over the dry creek bed. On the other bank, I could see moldering ancient stone walls, perhaps the remains of a quarry, or a mill. The scent of flowers, herbs, and chlorophyll hung in the warm and silent air, and I wondered where the bridge was for a moment - until I realized that I was, in fact, standing on it.

I crossed to the other side to take a few pictures, and stood there for a while, mulling over both the extreme antiquity and the deafening, eerie silence of the place. Part of me wanted to stay there for the rest of the day - maybe longer. Another part of me loudly objected that first, I'd let myself into the gate and someone might object to that, and secondly, atheist though I am, there's something inherently hair-raising about antique glades that would absolutely be occupied by the Old Gods. If you were the kind of person who believed in them.

I left, but reluctantly.

From the bridge, I decided to follow one of the marked trails all the way up to the canyon rim, pausing occasionally to get my bearings. Remnants of ancient pots scattered the ground everywhere I looked, as well as little indications of ancient walls and structures that had long crumbled into the earth. The landscape looked exactly like I'd imagined Greece to look before I'd ever visited here - and it reminded me of California, with its combination of verdant greenery and dry and rocky earth.

When I reached the top, the trail spat me out at the ancient Roman acropolis, which is fenced off, but which you can look into: as I stood there contemplating it, a friendly older British man passed me on the trail, wondering if he was going the right way to find the ancient cisterns - he said he was scouting in advance for his wife. After I told him that I unfortunately had no idea as I wasn't from around here, I walked off to the side of the agora area on a forested trail towards an overlook. All of a sudden, I startled three thick-bodied and electric-green lizards, which retreated in abject reptile panic into a mossy log, poking their heads out occasionally to keep an eye on me.

After I grew tired of trying to convince the lizards to let me adore them, I enjoyed the overlook, with its commanding view of other yellow-sided gorges, olive groves, and the ghostly foundations of the Basilica of the Archangel Michael, built on the lowland floor somewhere in the ballpark of AD 420-450, and destroyed sometime in the seventh century.

I kept following the main trail upwards in the direction of the ancient fortification tower atop the Pyrgi hill on my map - which I also noticed appeared to be where the cisterns were. Eventually, I came across an older British woman perched on a rock consulting a guide book.

"I think I saw your husband back that way," I said, as I felt I should probably report back. "Oh, of course," she replied, in an aristocratic London accent. "He's been charging ahead for 40 years," she added. "Incredible that anyone puts up with men."

I nodded in agreement, and she showed me where the cisterns were on the map: in fact, she was sitting just above them. While I don't find Roman cisterns to be inherently all that interesting, in that one cistern looks very much like another, they do have a sort of echoing grandeur that's worth seeing.

Finally, I walked up the path towards the crumbling remains of the tower-fort that sits at the crest of the hill, commanding an impressive view all over the ridges and canyons of the immediate area, and which . In front of the tower, I could see checker-boarded lines, inscribed in the dirt: archeologists think they might have been a low-budget way to emulate tiled marble flooring.

From the broad valley across from the main canyon, I could hear someone playing traditional Cretan music extremely loudly from a boom box, although I couldn't actually see the source: maybe a shepherd enjoying his Sunday afternoon somewhere in the thicket. Whatever it was, it added to the ambience.

I needed to walk back to my car, and I noticed that another trail looped back down to Orthi Petra, which would prevent me from having to retrace my steps. I followed the trail through olive groves, sheep fields, and past an impressive fenced thicket of pine and cypress trees, protected from the incursions of grazing livestock: after letting myself through another goat fence and scrambling down a washed out trail into the creekbed, I was back where I'd started.

I smelled like an unkempt armpit, I was covered in dust, and I was deliriously happy.

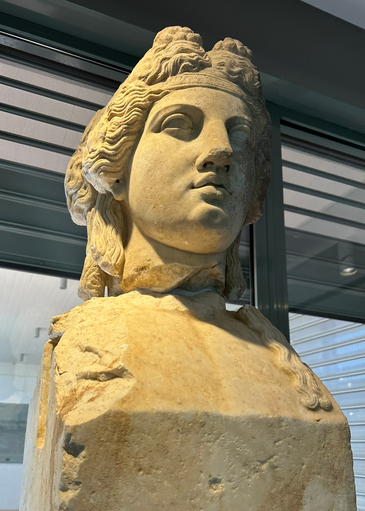

Don't miss the nearby Museum of Ancient Eleutherna, which opened in 2016 and elegantly presents a lot of the nicest stuff unearthed thus far in the ruins. Among the treasures here is the lower half of an Early Archaic statue of a standing woman (kore). Scientists now know that this statue is the highly-similar sister to the famous Lady of Auxerre at the Louvre, proving that Eleutherna is her hometown. Perhaps most impressive of all is a bronze "shield" (or a vessel of some kind) with a lion's head protruding from the center, dating back to between 830-730 BCE - an item almost certainly intended more for decoration than for combat, but cool as hell all the same.

If you're hungry before or after, I can highly suggest the dinosaur-haunch-like grilled pork chop at Taverna Giannousakis, which is located in the cute pottery-n'-tourism town of Margarites a few minutes from Eleutherna.

Archaeological Site of Aptera

On top of a mountain thirteen kilometers away from Chania, at the base of the snowy White Mountains, sits Aptera, a curious, compact Ancient Greek and Roman city whose main attraction is a small and well-restored theater. There's a number of other interesting ruins to explore at this site, though, including an enormous and eerie Ancient Roman cistern, and a petite and well-preserved Ancient Roman bath.

Once one of Crete's most important city-states during the Hellenistic period from the end of the 4th to the 3rd century BC, the city was originally called Artemis Aptera, after the goddess of the hunt. According to a myth first recorded in the 6th century AD, the name derives from the term "apteres" (featherless): the city was the site of an epic ancient throwdown between the Sirens and the Muses, and when the Sirens lost, they threw their suddenly-white feathers into the sea, forming the islands of Souda Bay.

Well, sure. Seems plausible enough to me.

I first visited the ancient theater, which at one point had a capacity of 3,700 spectators: it was restored fairly recently by archeologists, and you're allowed to sit contemplatively on the ancient rows of seats.

Original ancient Greek roads still run along the sides of the theater, which spectators once used to make their way into the complex. Seeing them made me think once again about how people remain people - doing basically the same stuff, entertaining ourselves in not-very-different ways, walking along recognizable roads - throughout the ages.

Proceeding onward, I paused for a bit at the small on-site museum, which is located inside of a 12th-century monastery that was active all the way up until 1964: the monastery's structure supposedly incorporates some recycled ancient stones with inscriptions on them, although I couldn't find them myself.

Walking deeper into the site, I lingered for a while at the 1st/2nd century AD Roman bath complex, with its well preserved doorways and its remnants of water-works and mosaic floors. It was hot, and I found myself wishing that Roman baths, with their accompanying luxury cold pools, still existed in this day and age.

From there, I walked towards the ancient Roman cisterns that supplied the complex with water long ago. These were truly enormous, their sheer size well concealed beneath curving, grass-covered roofs. Remarkably well-preserved ancient brick work still persists here, swallows nest in the dark eaves, and the cold scent of two-thousand-year old mold lingers in the air. I cannot entirely imagine how creepy it'd be at night.

Moving onwards, I diverted to go see the ancient Roman luxury villa preserved a little ways away from the main site. The well-preserved bases of columns and an ancient Roman peristyle courtyard hint at a long-gone, luxurious lifestyle.

As I left Aptera, I paused for a moment to consider the deceptively-old-looking Ottoman fortress that overlooks the sea near the ancient ruins. It only dates back to 1866, built by the Turks as part of an effort to get the Cretan locals back under control after they'd attempted a revolution: the interior is not open to the public, but it makes for a good picture.

Other Interesting Places to Visit

Souda Bay War Cemetery. A moving cemetery for soldiers killed in WWI and WWII, maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and overlooking the iconic deep-water port of Souda Bay near Chania. Read the heart-breaking inscriptions on the tomb stones.

Historical Museum of Crete (Heraklion). It's unfortunate that this museum is overshadowed by Heraklion's justifiably world-famous archealogical museum, as it's a wonderful and well-curated collection of interesting artifacts from Heraklion's long history after the 4th century AD. There's many interesting examples of local folk art, traditional icon painting, World War II history, Venetian and Ottoman history, contemporary art, and more.

Walking the Coast Near Anemos Beach in Chania. At the end of Anemos Beach in Chania, you'll find trails criss-crossing a lovely, rocky promontory overlooking the sea, alternating between a truly surreal-looking volcanic coastline, and lovely stands of pine trees. It's not exactly marked well on Google Maps, but it's in this area:

Tours

Portoplanet Tours - My parents first went on a trip organized by Portoplant owner Rallou and her late father George back in 2019, and I had the pleasure of connecting with Rallou again when I was in Crete. Her company can organize full private or small-group tours of Crete, with accommodation, drivers, interesting excursions (with a focus on local food), and more.

General Food Advice

Food prices in Crete are very reasonable. This will get you in trouble if you're from a very expensive American city, like me, because Cretan food (and Greek food in general) isn't just affordable, it also comes in gigantic portion sizes. I was traveling in Crete alone, and I eventually had to resign myself to accepting that I was not going to be able to finish a lot of the things I ordered. Not that I didn't try, because the food is delicious.

Vegetarians will do well in Crete: this is a culture that very much appreciates a meatless meal, and people traditionally don't eat meat all that often. There are many excellent salads and vegetable dishes on the local menu. And superb local cheeses. Vegans, you may have a rougher time of it.

Crete does have good seafood, but it's much less of an emphasis in the local cuisine than you might expect from a big-ass island in the Mediterranean sea. Per the Cretans I spoke to, it's a cultural thing as much as anything else: they're a people who are just more interested, as a general rule, in cheese, meat, and produce.

Seafood is also pretty seasonal and local, which is a good thing. Menus usually highlight if fish is frozen (IE, probably came from elsewhere) or not. I was able to get local tiny shrimp - delicious! - sea bass, squid, and some other things when I was there in early May. There's also some lovely stuff on offer at the local fish markets, which might be fun to cook with if you're staying in a place with a kitchen.

Try the antikristos, which is Crete's extremely amusing term for roasted lamb, cooked on a sort of rotating metal grate over an open flame. You do not need to be delicate about it: people in Crete like to eat their lamb with their hands, as do I.

If people like you at all, they will give you raki, often stuff home-made by somebody's cousin in a village somewhere. You will end up with plastic bottles of raki in your pockets and in your stuff. In my opinion, this is a good thing, because raki is delicious, and also goes down disturbingly easily for a moonshine-like variety of booze.

Greeks eat dinner later than most of us Puritan-poisoned Americans do, around 8:30 or 9:00 PM. If you want to get a table at a restaurant without making a reservation first, get there before 8:00 PM. Restaurants also close late, usually around 11:30 or midnight.

Suggested Restaurants

Here's a list of restaurants I liked in Crete, in no particular order.

HERAKLION

Apiri - Creative Greek food with a focus on local ingredients and some nice outdoor seating options. I absolutely loved the smoked sea bass with lemon sauce, tiny cod croquettes, and seaweed salad, to such an extent that I came back twice. Get there early, or make a reservation. It's popular with both tourists and locals.

Parasties - Upscale, albeit still quite reasonably priced, dining with a number of creative dishes, set in a cozy and interesting historical building near the water in Heraklion. I loved the crawfish and fennel bisque. Very friendly service. Also, there is a resident cat.

Pastry History Museum - Heraklion's best bakery also features one of the world's only history museums dedicated to pastry, and definitely the world's only reproduction of the Knossos Palace made entirely out of fondant. Run by the extremely friendly Mr. Koumakis, who also teaches entertaining, eccentric baking classes in the bakery's Willy-Wonka themed basement (Porto Planet can arrange this for you). Really must be seen to be believed.

Paradosiakon (Georgios I. Sifakis) - Meat-centric Greek restaurant with a lovely outdoor courtyard in the middle of town. I enjoyed the smoked pork with honey, as well as the ultra-airy fried eggplant.

Cooking With Love - Delightful little lunch joint run by extremely friendly local women, with a rotating display of dishes each day. Get there early before the moussaka runs out. Portions are enormous. Cash-only.

Paradosiakí Taverna Xylouris - Popular, big local taverna situated across the street from the sea a little bit out of town, with excellent antikristo lamb and lemon baked potatoes.

Phyllosophies - Deservedly ultra-popular bakery and cafe specializing in bougatsa, a delicious sort of flat phyllo-dough pie, coming in both sweet and savory varieties.

Kalamaki Meat Bar - An excellent joint for souvlaki and gyros - you can order meat skewers on their own, or in a wrap.

CHANIA

Salis - Creative Greek food right on the water, as well as some nice cocktails (which aren't super common in Cretan restaurants). Get the eggplant with fermented fava beans and thyme honey.

The Well of the Turk - Excellent food with a distinct Turkish/Middle Eastern flair located amidst the warren of weird little allies and backstreets in old Chania, and pleasant outdoor seating. Will bring you chili sauce if you ask, which I did. I enjoyed the fried zucchini blossoms and the lahmajun.

Authentico Ice Cream Shop - I'm not even that into ice cream, and this place was incredible. Lots of interesting flavors - get the strawberry and Lila Pause (a strawberry/chocolate candy bar).

Pinaleon Fine Kitchen - Airy dining room with great traditional Greek food and a number of interesting lunch specials - you can see what's on offer in the back before you make a selection. I really enjoyed the braised pork with prunes, served with greens and mushrooms cooked in avgolemono sauce.

Chrisostomos - Old-school feeling Cretan joint with great Cretan salads and meat dishes. Try the stifado (Greek braised beef and onion stew).

9beaufort - Seafood on the water in the pleasant and relatively quiet Nea Chora Beach area, to the left of Chania's main tourist center. Don't miss the tiny fried shrimp, which seem to be locally caught (unlike the bigger shrimp you see on other menus).

Pork to Beef Wild - Creative grilled-meat centric wraps and sandwiches (although there are some great-looking vegetarian options too). Try the pulled pork wrap with caramelized mushroom, onion, fried potatoes, and pickled apple.

ELSEWHERE

Le Mythe d'Aphrodite, Kalamaki - Seaside restaurant in the quiet, windy, and beloved by Germans town of Kalamaki on Crete's Southern coast.. Features the best moussaka I've ever had, served by the friendly family who own the place. Seriously, I think about that moussaka a lot.