We Have to Stop Using Facebook and X to Warn People About Disasters

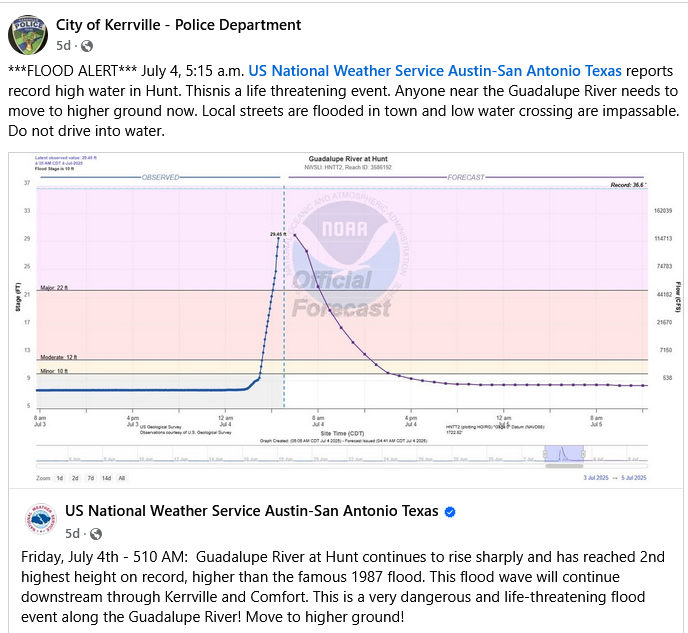

In the early morning hours of July 4th, as the Guadalupe River reached catastrophic heights, city officials in Kerr County, Texas turned to an all-too familiar mechanism for getting the word out to area residents: Facebook.

While the National Weather Service had been issuing warnings across multiple platforms about the prospect of flash flooding in the area since the afternoon of July 3rd, local officials in Kerrville appear to have waited until 5:16 a.m. on Friday to start doing the same.

As flash floods ripped through the area, Kerrville's police department, sheriff, and City Hall posted on Facebook to warn locals to find higher ground, to exercise caution while driving, and that "severe weather may impact many of today's scheduled July 4th events."

Insofar as anyone knows right now, Facebook was also the only messaging platform that Kerr County officials used to communicate with the public during the deadliest hours of the still-unfolding Guadalupe River flash flood tragedy.

I wish I could tell you that Kerr County's dangerous over-reliance on a single, massively flawed social media platform was just a small-town Texas thing, an unfortunate but thankfully rare aberration in American disaster communications practices.

Unfortunately, it's not.

I suspect that the terrible truth is that far too many local authorities are now communicating important messages to the public exclusively via Facebook, Twitter, or some combination therein. And while I say this with the clear caveat that I've been unable to find little recent academic research or reporting on this issue, I've seen enough anecdotal evidence pointing in this direction to scare me.

It's 2025. We're living in a time when social media oligarchs have stopped even pretending to care about the greater good, their platforms have been intentionally engineered to hide non-brainrot information from its users, young people have largely fled to TikTok, and the federal government is starting to mandate using Twitter for official communications.

In other words, we may be glimpsing the leading edge of a big problem with how American local governments communicate with the public about stuff that can kill them.

Let's turn to the sad and still unfolding story of Twitter (X), Facebook, and those distressingly loud wireless emergency alerts, or WEAs, that we all occasionally get on our phones.

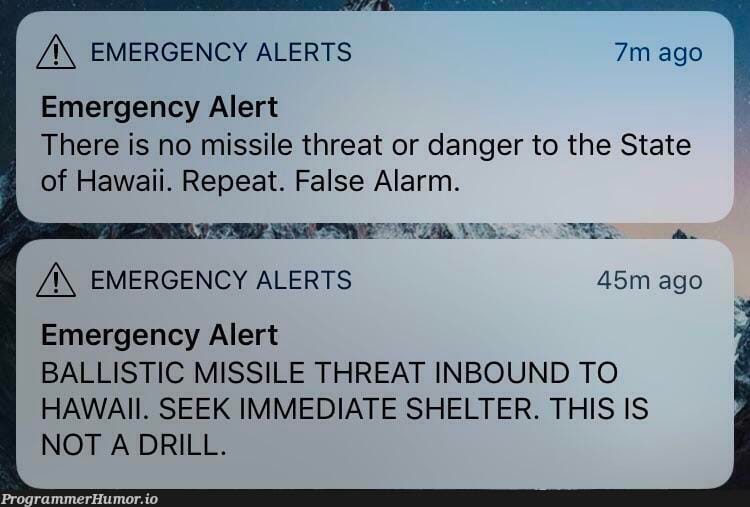

In 2018, FEMA's Integrated Public Alert & Warning System (IPAWS) made it possible for government officials to embed web links into WEA messages, which recipients could follow to find more detailed information on unfolding disasters.

However, according to FEMA's own documentation, some government officials (or, in FEMA's terms, Alerting Authorities) who took advantage of this new WEA capacity found that their websites crashed under the sudden deluge of hits.

Unfortunately, both federal and local authorities didn't view this situation as a wake-up call about modernizing government-owned websites to handle occasional surges in demand during disasters. Instead, many local authorities decided to replace links to their own websites in WEAs with links out to Twitter and Facebook - and while FEMA didn't explicitly endorse this practice, they also didn't discourage it, either.

For a while, this imperfect decision to rely on privately-owned social media companies for crucial context on disasters mostly worked.

After all, during the glory days of Twitter as the world's preeminent disaster communications platform, back before Musk flew in like an incontinent seagull and shat all over the place, you didn't need to log in or even have an account to view posts.

But shit, that seagull did.

Citing a need to "minimize the degradation of our service and platform from unauthorized scraping of Twitter data," Musk promptly decided to block all Twitter material to viewers who weren't logged in. (Musk claimed at the time that this was a "temporary emergency measure" - but as I write this in July 2025, the change is still in place).

This move swiftly led to entirely predictable consequences.

In July 2023, an AMBER alert sent to Missouri resident's mobile phones linked out to Twitter to view further details, as had been typical there for years. Except this time, thank to Musk's decision to shut off access to users who aren't logged in, many people were suddenly unable to view the relevant details.

This incident caused considerable outcry, and Musk's new Twitter leadership eventually, and likely begrudgingly, verified Missouri's official account with a silver badge, which permitted non-logged in users to view AMBER alert information.

In a more recent, similar incident in January 2025, California residents complained after they received a California Highway Patrol AMBER alert with a link out to X, which people many were unable to view without logging in. (Not that this was the first such case - others were reporting this issue with CHP alerts on Reddit well before January 2025).

And yet, despite these consistent and well-documented issues with Twitter links in WEAs, government agencies keep using them. As of this year, Missouri continues to issue AMBER alerts with a Twitter link, as part of its official AMBER alert policy. Meawhile, CHP continues to primarily post alerts to a verified account on Twitter (though a spokesperson claimed in May that they were working on retooling the CHP website so that they could post alerts there, too).

Unfortunately, while some agencies have figured out that they need to work with Twitter to get a verified badge if they want the public to view their alert messages, others still seem, over two and a half years into the public visibility changes, to have never got the memo. And Twitter/X certainly don't seem to have made any effort to warn government agencies that they need to get verified, either.

I decided to look into how frequently government agencies issue WEAs that link out to unverified Twitter pages that can't be viewed without logging in, using PBS's excellent website that compiles US emergency alerts into one centralized location.

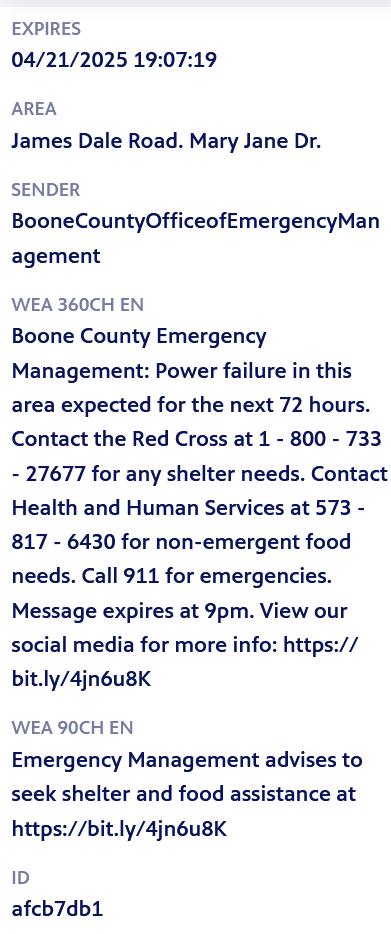

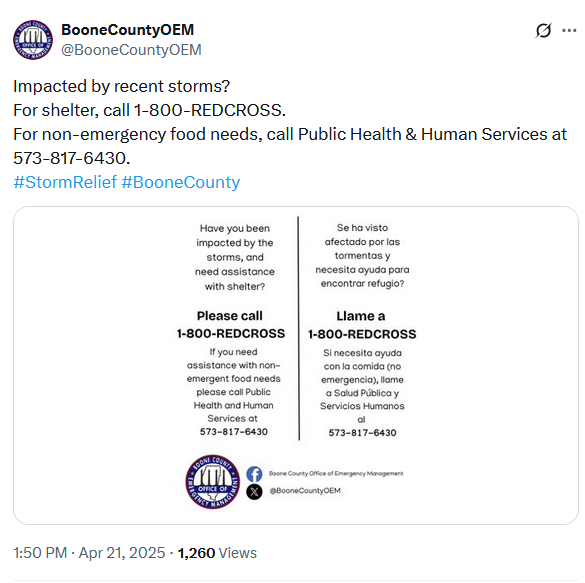

Here's one example: on April 21st of this year, authorities from the Boone County, Missouri Office of Emergency Management sent out a WEA message alerting locals to a power outage from local storms, which included a link to a non-verified Twitter page for further information:

boone county's WEA and the post it linked out to

While it appears like users without Twitter accounts can view the individual post, that's it.

If local residents want to view other messages from the Boone County OEM Twitter profile - which they very well might want to do during an emergency - then they'll be greeted with an empty profile page and this text:

"@BooneCountyOEM hasn’t posted. When they do, their posts will show up here."

Except, crucially, this isn't true. Boone County actually posts alerts very frequently to its Twitter page.

Which means that Twitter isn't just locking Boone County's emergency alerts away from people who aren't logged in, it's actively deceiving them about how frequently the government account actually posts information.

Observe the difference between what you see on the Boone County, profile if you're logged out (to the left), versus what you see if you're logged in:

Boone County OEM has in fact posted some pretty important information recently, Elon Musk

Other examples of unverified Twitter accounts that local government WEA messages have linked out to in the last year (per what I could determine from the PBS data) include Oklahoma's OHPAlerts, Washington's WSP Missing Person Alerts, and Wisconsin's Silver Alerts.

Whille government agencies reliance on Twitter to notify people about lifesaving information in the year of our Lord 2025 is really, really, bad, it's not the worst way to notify the public about imminent death and destruction.

The worst way is Facebook.

While Twitter's changes to public post visibility are at least still sort of recent, Facebook has pretty much always exposed minimal data to users who aren't logged in.

There has never, ever been a good excuse for linking out to Facebook in a WEA. Or, even worse, posting vital information to Facebook without bothering to send a WEA out to local phones at all. Unfortunately, way too many authorities responsible for keeping the public safe continue to do just that. And they're not just in Kerr County, Texas.

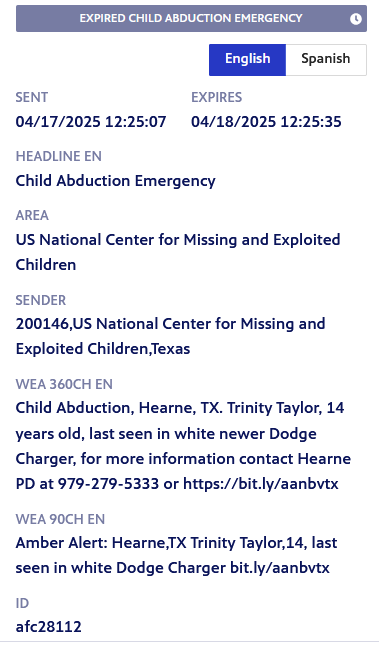

In April, authorities in Hearne, Texas sent out an AMBER alert WEA that linked out a Facebook page for the Amber Alert Network Brazos Valley while encouraging residents to send in information about a child abduction event.

While they did provide a phone number in original message, in addition to the link, anyone without a prior Facebook account may not have been able to clearly view the further information. Including, most importantly, a photograph of the missing child.

Other recent examples of WEAs that link out to Facebook, out of a depressingly large number, include:

- Utah's South Salt Lake Fire Department calling for an immediate evacuation due to a gas leak, and directing impacted people to a Facebook link for updates.

- California's Kern County sending out a fire evacuation alert which linked out to a Facebook page for further updates.

- Florida's Martin County Fire Rescue directing people to monitor "social media for updates" about a recent fire event without providing a link out to anywhere at all. When I searched for their social media, I found two equally publicly-locked down Facebook and Instagram pages.

- Washington's Lincoln County sending out a fire evacuation warning to area residents, and vaguely advising that they check the "LCSO facebook" for updates on the danger - again, without even providing a link. A month before, official in Washington's Douglas County also advised people to check a local Facebook page without providing a link for a Level 2 fire evacuation event.

- An AMBER alert from Hawaii's Maui Police referring WEA recipients to their Facebook page to view a photograph of the missing child - again, with no actual link provided.

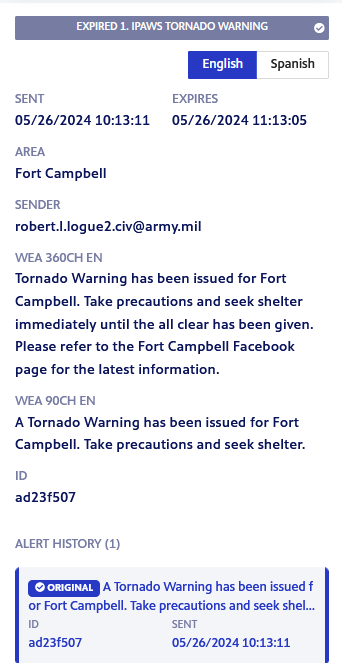

Even the U.S. military relies on Facebook for disaster communications sometimes, like in the below example from May, 2024 in which authorities at Fort Campbell in Kentucky sent out a tornado warning WEA and referred receivers to the installation's Facebook page for "the latest information":

Local officials are also still relying on Facebook and Twitter to communicate information that, while less imminently dangerous than that usually conveyed in in a WEA, is still really important.

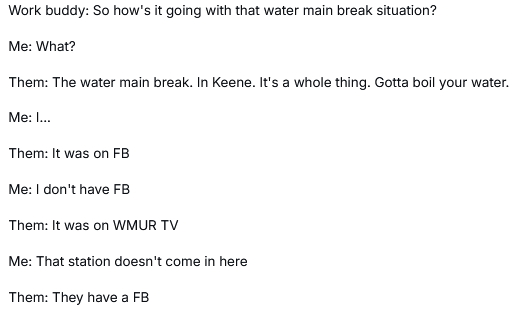

Like, say, boil water advisories.

While I couldn't find any comprehensive data on how frequently local officials turn to Facebook or Twitter to tell the public that their tap water is now trying to kill them, I have come across some anecdotal evidence from social media.

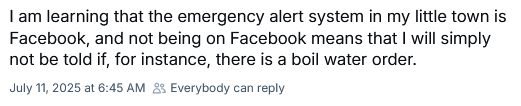

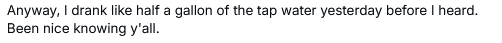

Take the example of this Bluesky user in New Hampshire, who discovered too late that their small town only communicated a boil water order via Facebook and local cable TV:

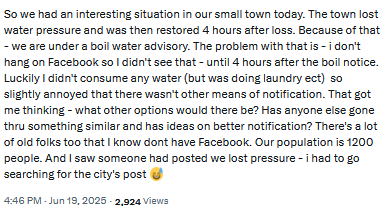

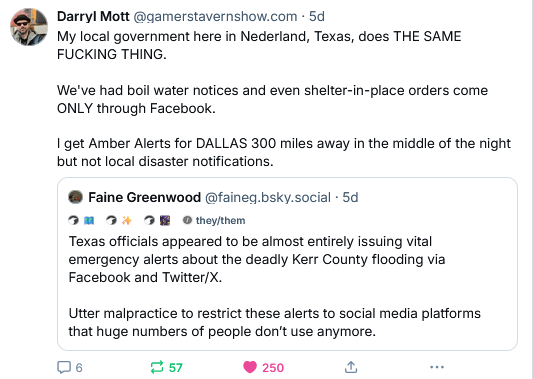

Or these other Bluesky and Twitter users who recently missed similar boil water notifications:

While American government officials may not have intended to create a hellscape in which people have cough up their data to actively malevolent tech companies to access information about natural disasters and boil water advisories, we've ended up in this dark place anyway.

So how did we get here? And what can we do about it?

If you've got this far, you probably already understand why it's really bad that Facebook and Twitter are still dominating local government disaster communications in 2025. But just in case you don't, let me explain a bit further.

Here's the first reason: despite what Musk and Zuckerberg might ever more desperately insist, Facebook and Twitter are both a lot less popular than they used to be.

While Facebook was still the second-most popular social media application amongst American adults in 2024, usership amongst younger Americans has tanked over the last decade. A mere 32% of teens said that they used Facebook in 2024, and at least anecdotally, quite a bit of that use may be devoted to things like "wishing Grandma a happy birthday, then immediately switching over to TikTok," and "grudgingly using Facebook Marketplace to find cheap stuff."

If you look at which age groups still use Facebook on a weekly basis, the gap becomes even more clear. According to this set of April 2024 data, a solid 56% of weekly Facebook users are Gen X or older - and just 13% are members of Gen Z.

Arguably, Twitter's decline in popularity since Elon's 2022 takeover has been even worse.

Twitter was never very popular among mainstream audiences - for as long as it's existed, it's been a niche platform for a certain kind of opinionated, usually older, weirdo. And unsurprisingly, Elon Musk's ceaseless work to transform Twitter into a bargain-bin Stormfront knock-off hasn't translated into more mainstream appeal.

Although Musk unsurprisingly releases as little data as possible on Twitter's current popularity, pretty much every observer agrees that things aren't looking good. In the European Union, where Musk is required by law to share information about monthly users (unlike in the US), his big stupid website has lost 10.5% of users - over 11 million - since August 2024.

All these popularity stats add up to one clear conclusion.

In 2025, if you're posting vital information exclusively to Twitter and Facebook, then you're guaranteeing that a whole lot of impacted people are simply never going to see it. Especially the very young and the very old. And they likely don't even know that Facebook and Twitter are where they should be looking.

Then, there's the fact that you need to log in with an existing account just to view posts on both Facebook and Twitter in 2025, as we've already discussed above. This fact alone should have convinced American authorities to slow their roll on ever turning to Facebook as a core disaster communications platform. And Musk's decision to shut the public out of Twitter posts in early 2023 should have provoked a mass exodus to other solutions.

But sadly, that's not what happened.

Finally, there's the eternal specter of The Algorithm.

While Facebook and Twitter have been manipulating what users see for a long time, they've stepped these efforts up considerably in the last five years. When you're scrolling these websites today, you're likely going to see a confused mish-mash of posts from people you follow and people you've never heard of before, spanning multiple weeks or even months.

What this means is that even if someone impacted by disaster does happen to have a Facebook or an X account, and is already following the relevant local officials, it's unlikely that they'll actually see posts about an emerging disaster in their area in a timely fashion on their feed.

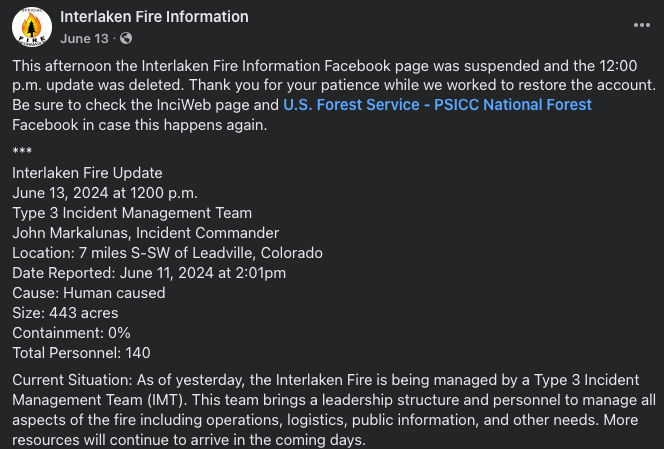

This manipulation of user attention extends beyond news feeds. All too often, Facebook and Twitter are now actively blocking or removing emergency-related posts for mysterious and presumably often automated reasons.

A Washington Post investigation in September 2024 found over 40 instances of Facebook removing timely emergency warnings about wildfires, which had been posted by government officials, first responders, volunteers, and media outlets. Reporters in Colorado documented similar examples of Facebook continuously removing wildfire updates posted by local officials.

Facebook's moderation tools, which appeared to focus in particular on posts that linked out to other websites, claimed that these posts were spam: meanwhile, Facebook told the Washington Post that they weren't previously aware of the problem. As we enter another Western fire season, it's unclear to me if Meta has actually resolved this problem - or if officials will have to continue to battle Facebook simply to post timely information.

Nor is it easy for users to search for information about unfolding disasters in their area on Facebook and Twitter. While Facebook's search functionality was always bad, its automated moderation is now so crap that, in March 2025, the website blocked Australians from searching for information about the imminent arrival of Cyclone Alfred, claiming that some "content in these posts goes against our Community Standards."

At the same time, Twitter's once reasonably robust search functionality has been massively degraded since Elon took over - a decline that's been extremely noticeable to me as someone who's spent a lot of time using Twitter to monitor unfolding disasters since 2008.

Once, my search results for "top" regarding an emergency situation would be largely dominated by reputable accounts posting relevant information. Today, they're filled with only vaguely-adjacent crap from random idiots who paid for a blue checkmark (and the Latest results are, somehow, even worse). We collectively witnessed the dire consequences of these changes during the Lahaina wildfires in 2023 and again during Hurricane Helene and Hurricane Milton in 2024, all events in which Elon's Twitter (as well as Facebook and TikTok) became a key vector for the spread of ruinously batshit disaster disinformation.

Nor do Meta and X have any mechanisms for overriding their platform's foul default behavior during disasters. There's no social media equivalent of a WEA alert that's sent out to all mobile phones within radius.

Ultimately, Zuck and Musk both believe that using the algorithm to sell you drop-shipped crap and show you racist AI-generated posts about eugenics takes precedence above all. Up to and including flash floods, wildfires, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions.

And they're not going to stop doing that unless someone makes them.

I vividly remember the early days of social-media based disaster communications, back in the late 2000s. I was still in college, and I was working at a Tulane on-campus research center that did some early analytical work on how people used Twitter to communicate during disasters.

At the time, during that precious last gasp of cultural optimism about the future of technology, it seemed like a really good idea to convince local authorities to post disaster information on social media platforms, in addition to more traditional platforms like radio, television, and government websites.

Not long afterwards, American local government's shift towards communicating with the public online about disasters arguably kicked into overdrive after the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, which drove far more attention to both the good - and really bad - aspects of following crises in real time on social media.

While it's difficult to find recent numbers on this, I think we can safely assume that a solid majority of American local governments have some kind of social media presence in 2025. We can also assume that mostly, they're using Facebook and Twitter.

Unfortunately, that well-meaning push to get local government on social media during the 2010s failed to anticipate two things: that some officials would become disturbingly dependent on just one or two privately-owned social media platforms for conveying disaster information to the public, and that those social media platforms would become evil.

Someone who's an actual expert should write a lengthy book on how we got to this particularly dangerous place with online disaster communications, but in the interest of time, I'll try to summarize.

And please, keep this in mind: I'm not a specialist in disaster communication. I'm just some guy who's worked in other research areas that overlap with it a bit.

First, there's the problem of increasing reliance on contractors and outside vendors to build government home pages, which all too often seems to result in local officials having to contact a third-party consultant based in God knows where to make timely updates to their own websites.

There's also genuine concerns over sudden spikes in web traffic crashing locally-administered websites, as expressed by a Tennessee government representative as they justified a recent shift from posting AMBER alert details on Twitter to, well, posting them on Facebook.

Meanwhile, it's still relatively effortless for government employees to put a post up on Facebook, or Twitter. No technical skill required.

With all these factors in mind, it's not exactly shocking that many government employees with public communications responsibilities decided to start relying on social media to share breaking information.

Second, there's good-old fashioned technological inertia.

Most everyone agrees that governments take a long time to adopt new technology - even if, in our current era of tech company perfidy, this slow moving pace has started to sound like more of a feature then a bug. (And trust me, I understand this issue viscerally, speaking as someone who's been a state government technology contractor before).

While officials did eventually largely figure out how to use Twitter and Facebook for disaster communications, the world didn't stop there. Unfortunately, it never does.

Social media, and the larger Internet, is an inherently chaotic and ever-changing space. If you want to be heard in this hostile ecosystem, you have to be prepared to constantly shift tactics and approaches. While I know this is a tall order for government employees, who are often working with miserly budgets, time and regulatory constraints, and not-super-tech-savvy staff, there's also no way around this reality.

Something has to change.

Because relying on Facebook and Twitter for disaster communications in 2024 isn't just unsustainable, it's going to get people killed.

It almost certainly already has.

What, then, should we be doing instead of relying on Facebook and Twitter to communicate vital disaster information to the public?

Keeping in mind that I'm not actually a crisis communications specialist, here's a few off-the-top-of-my-head ideas. I'd like to hear yours, too.

Call for local legislation that will require officials to use multiple communications channels during disaster and crises. The social media landscape is intensely fragmented right now, and I don't see that changing. I also feel pretty confident the MAGA federal government couldn't care less about any of this.

But on the local level, we absolutely can push our lawmakers to require that officials post key emergency updates on multiple online platforms. And we should demand that at least one of these platforms must not require a log-in simply to view the information. Like, say, a government website.

This rule should also apply to WEAs sent to mobile phones. If these messages link out to further information, at least one of those links has to be to a public platform, preferably one controlled by authorities themselves.

Yes, mandating a multi-platform approach is almost certainly going to require some extra training for officials, or even, in some cases, hiring new personnel. It may also require updating or acquiring new software tools to facilitate this kind of rapid cross-posting approach. So be it: paying for this to happen needs to be baked into disaster response funding.

A return to posting vital updates on government-controlled websites that are designed for disaster communications. Yes, I know there's a sea of contracts, protocols, technical knowledge deficits, and funding issues that serve as barriers to building half-decent government websites in 2025.

I know that tons of innocent people have been conditioned like Pavlov's poor drooling dogs to look to social media, not actual government websites, for real-time updates on crisis situations.

I know that big tech is currently working overtime to ensure that people rely on ChatGPT, a service that inherently can't deliver meaningful disaster updates, for everything they do online.

But it was a terrible, deadly mistake when much of government decided to outsource control of their communications to privately-owned social media companies. We need to change this if we want our communities to be able to protect themselves in the future.

I believe it is in fact absolutely possible for all states to build websites where they can post real-time emergency alert information for public consumption, in such a way that they don't have to worry about sudden crashes or maintenance issues. And they don't have to keep reinventing the wheel, or rely entirely on in-house IT talent: there are vendors out there that can help governments create these websites.

Authorities in some states already seem to consistently link outwards to actual websites that they maintain themselves in their emergency alerts, like certain agencies in Virginia, and Massachusetts, as well as in a number of municipalities in California. Hell, PBS has even put together an aforementioned platform that partially does this on a national level. (Which I very much hope survives imminent MAGA-led cuts to the PBS budget).

Disaster information dissemination is also a place where decentralized social media protocols, like the AT Protocol that Bluesky runs on, could potentially come in handy. Someone should throw some money and time at that.

The bottom line is this: officials should keep posting emergency information to as many social media platforms as possible, including Twitter and Facebook, preferably with verified accounts. A widespread approach is key.

But they also need to be posting this information on websites that aren't controlled by capricious tech billionaires.

excellent question about Facebook blocking searches for disaster information, ABC Australia

Suck it up, we need to post more videos. Look, I'm a text-based Internet person myself.

But if you want to warn young people about things that could imminently kill them, you need to reach them where they actually are. And those places are pretty overwhelmingly video-based platforms like TikTok and YouTube.

We need to prioritize "learning to make basic informational videos" for everyone who's in charge of communicating with the public.

I'm not saying that every single 55-year-old emergency management and county official in America needs to learn to dance to hyperpop TikTok memes about boil water advisories. But I mean, probably more of them should be doing that.

Federally-mandated rules requiring big social media companies to make it easy to see local disaster alerts. I know, putting rules like this in place sounds like a wild-eyed pipe dream in our current moment of collective federal government derangement.

But hey, let's fantasize a little.

Big social media companies could be legally mandated to surface official disaster communications to the top of user's content feeds when crisis strikes, for all users who the company believes to be in the right geographic radius. (For once, we could put that creepy geographic data they're constantly trying to collect on everybody to good use).

Facebook already does provide a Local Alerts feature for local government and first responders, which appears to send push notifications to users who are already following a given official page, as well as people following other relevant local pages. However, it's unclear how widely these are used, how effective they are, or how many potential users are aware that they even exist.

The public documentation on Meta's website about Local Alerts minimal, and I couldn't find much of anything written about them over the last few years. Nor does Facebook boost these alerts for free - but Meta helpfully suggests that you can pay them if "you want to try to reach more people and get more views." But I guess I'll give Meta this: they do, allegedly, exist.

Meanwhile, Twitter used to have a similar so-called Twitter Alerts program for certain institutional users, but this feature appears to have been quietly discontinued at some point in 2019. I couldn't find any information on why this program was ended, but I'll keep digging.

Everybody should buy a weather radio. This doesn't have anything to do with Facebook or Twitter, but I wanted to repeat it here. Because everyone, especially people living in areas prone to natural disasters, should really have a weather radio. Perhaps, someday, we'll even get a government that's willing to subsidize this. Here's some information on how weather radios work from the NOAA and the NWS.

Stay safe out there.

And please, don't trust Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk to keep you alive.