Why I Care About Drones: Part 2

A nightmarish airborne robot-eye, piloted by unknown and possibly unknowable forces operating from an undisclosed location in a secret command-center, lit only by blinking red LED lights. A far-flying remote controlled warplane designed by hubris-poisoned and dead-eyed engineers, hauling a payload of knife-throwing missiles to rain down on enemies of the state. An endless, buzzing swarm of tiny wasp-bots deployed by a super-villain wearing a metallic costume - lifeless creatures simulating life, which ruthlessly pursue heroic main characters through grimy cyber-punk streets bathed in blinking neon lights.

In 2013, these were the images that sprang to mind when most of us thought about drones. That is, when we thought about them at all. Unmanned aerial vehicles simply weren't a regular topic of conversation for semi-normal people back then. The people who did pay attention to drones were most often aviation and model-aircraft nerds, or were, sometimes, the political wonks and reporters cursed to closely follow the already aging, endlessly demoralizing War on Terror. Drones were distant, mysterious, advanced military technologies that allowed empires to keep empiring, albeit in a shadowy way that many, even within the armed forces, considered to be somewhat less than honorable. They were not, most of us assumed, likely to suddenly show up in thier fully weaponized, hideous glory over our backyard grill.

Up until the fall of 2013, I was a member of that great mass of humanity who had spend very little time thinking about drones.

Sure, I was dimly aware of them, thanks to my work as a reporter who covered international affairs and technology. I was even friends with people who reported on their doings and their technological advances for a living. But I didn't think that drones had much to do with my interests, which lay much more with the implications and uses of technologies available to average people - smartphones, social media, the wilds of the greater Internet - and much less with the grim arena of America's wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

My indifference lasted until the moment I saw my first drone, a mysterious, bone-white object buzzing weirdly in the blue autumn sky above Stanford's soccer field, where I was studying for a master’s degree. I looked at the DJI Phantom drone, and as I did, some lizard-like part of my brain convinced me that the drone itself was looking back at me. Even if I knew, intellectually, that a human was piloting it, iy still felt sentient, somehow. A thing that could see, and could also be seen, an object that moved in mysterious ways.

In that instant of mutual regard between human and unidentified flying object, I realized something that would, cliched as it inevitably sounds, change my life. Because I wasn't staring down an aircraft: I was staring down a flying camera, an aerial data-collection machine with a decent global positioning system and a small yet eery amount of self-determination. A semi-miraculous, midly upsetting device that anyone with both $800 bucks and functional thumbs could buy online on a whim.

After I followed the drone back to its student owners - who claimed they wanted to start a drone burrit0--delivery service, a dream that far as I know has yet to manifest - I started thinking about all the people I knew who could use a freaky little flying camera. War reporters, like the twitchy and wine-cooler-quaffing veterans I used to hang out with at my reporting job in Cambodia , people who far too clearly remembered the sound of bullets whiffing past their heads during battles in places like Huế, Syria, and Baghdad. Maybe, I reasoned, people like them could use drones to clearly document the horrors of warfare without getting blown up themselves.

I also thought of the humanitarian aid workers I knew, whose jobs required them to know how many family homes had just been consumed by volcanic lava, or what pathways were still available for escape during cataclysmic flooding, or how many people were desperately trying to cross international borders to safety during a war. A drone might be able to help them answer those life-or-death questions, at a price point far more accessible, and far more available on-demand to underpaid relief workers, than hiring a manned aircraft or tasking a satellite.

Soon after I walked away from that fateful, perfectly manicured soccer field, I started attending meetings at the Stanford Drone Club, where I learned (as I’ve written earlier) that building a drone from a jumble of electronic parts, and flying one, was vastly easier to do than both the US military-industrial complex and the sci-fi film industry had led me to believe.

I purchased a DJI Phantom of my own, which I flew over Stanford’s dry campus lake, where I began to experiment with shooting my own gods-eye view of the bucolic university and its equally bucolic parks and oak-filled, drought-dried hills. I also started hanging around with the charmingly weird assemblage of software engineers, aviation nerds, robotics experts, and avant-garde artists that defined the drone scene in the Bay Area - people who exposed me to ideas spanning the gamut from bracingly brilliant to creepily crackpot about what humanity could do with flying camera robots in the very near future.

And as I read more about drones and what people were doing with them in 2013, I started to dig into what the rest of the planet was doing with this singularly accessible, if still somewhat little-known, consumer device that could let anyone look at the world from the same perspective as that enjoyed by a hawk, or the player of a video game about simulated cities, or an airplane pilot.

Or a god.

In November 2013, only a month after I'd seen my first drone, and only a few weeks before Jeff Bezos would make his ill-fated announcement about Amazon's imminent adoption of drone delivery, the people of the Philippines were hit with a horrifically damaging typhoon. As citizens and aid workers struggled to make sense of the sheer scale of the damage, Filipino drone pilots began posting photos and videos of the wreckage online: their footage was soon followed by drone imagery collected by international journalists and aid workers, creating an unprecedented, if not exactly well-coordinated or organized, collection of aerial data in the wake of a major disaster. Disaster drones had, all of a sudden, come of age.

Experts working in both humanitarian aid and journalism (and me, in my grad school apartment across from a Safeway) found themselves scrambling to figure out what to make of this sudden new explosion of potentially useful aerial data - information which could be collected by anyone who had a drone, not just by authorized disaster responders or professional photographers.

Could the data be meaningfully crowd-sourced to create maps that could help disaster rebuilding efforts, as the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team attempted to do? How could drone pilots be better organized, or made to fit somehow into the incredibly complex and often inflexible systems used by humanitarian aid workers for decades? If people were going to start flying drones willy-nilly over disasters, what was that going to mean for manned aircraft flying over the same areas? If aid workers started flying drones over conflict zones, would people on the ground confuse them for armed drones - or could drone-collected data be used by bad actors to harm people already made vulnerable by disasters?

There's enough here to keep me occupied for a very long time, I thought to myself, as I read through the questions that were just starting to emerge about disaster drones online.

I am bad at predicting the future - not that I believe anyone is good at it. But in that particular, singular instance, I think I nailed it.

Soon after Haiyan, I started to look at how people were using small, cheap drones in Ukraine.

At the end of 2013, Kyiv was on fire. Millions of people surged into the street to protest against the corrupt and heavily Russian-influenced regime of Viktor Yanukovych, who resided in a splendid riverside mansion and maintained a private zoo filled with big cats and tropical birds. People camped out in the capital's vast Euromaidan square, filling it with candles and lights throughout the night, calling ceaselessly for the President's ouster. Late into the protests, when Yanukovych felt his power slipping away, security forces would fire weapons into the same crowd, killing dozens of people.

Ukrainian reporters and activists filled YouTube with powerful videos from the protests – and most impressively, many of these videos were shot with drones, both during the day and at night, giving the entire world a stunning perspective of just how many people had taken to the streets to kick out a deeply unpopular despot. These Ukrainians had become some of the first people to start using consumer and DIY drones for journalism, and I was riveted by their work, and the possibilities that it invited.

It was not surprising that Ukraine took so early to drones. Ukraine had been a center for technological excellence within the bounds of the former USSR, and when the Soviet empire crumbled, many of those talented engineering minds stayed put. By the late 2010s, many Ukrainians worked as software developers and engineers for both international and local companies. Others worked in the aviation sector, building and testing aircraft.

Many were part of the same drone-nerd subculture that the people I was hanging out with in Silicon Valley belonged to, hanging out in the same web-forums and Facebook groups, tinkering with the same electronic components and off-the-shelf drone offerings. All this ambient expertise meant that Ukrainian activists were very quickly able to start pushing headline-grabbing aerial video of the protests on social media, steering the narrative in ways that Yanukovych's supporters - and Russia - almost certainly didn't anticipate, a sudden challenge to long-established norms around who could afford to capture footage from the sky, and who couldn't.

When an enraged Putin decided to invade Ukraine's Donbas border regions and the Crimean peninsula in early 2014, Ukraine's drone hobbyists were ready for that fight, too. As a nasty, low-level border conflict simmered over the course of eight years, Ukrainian drone pilots would spend the next eight years getting better and better at using drones, both for collecting information from the air, and for dropping bombs. In 2014, Ukrainian engineers would launch Aerorozvidka, an organization run mostly by civilians that occupied itself with building cheap, small drones to fight against Russia. Eight years later, the same organization's drones would play a key role in repelling the progress of Russian tanks towards Kyiv.

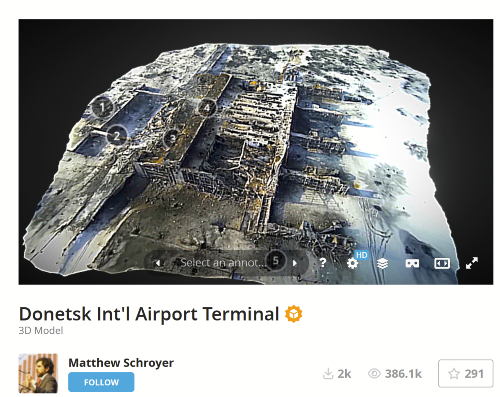

In the midst of Ukrainian fighter's last defense of Donetsk International Airport in January 2015, drone journalists flew a drone over the bombed-out building. In a strikingly innovative move for the time, Matthew Schroyer of the newly-founded Professional Society of Drone Journalists used consumer-level photogrammetry tools to create an interactive 3D map of the structure, derived from the drone video footage. To me, the 3D model straddled the threshold between real-world footage and the isometric jewel-box worldview of a simulation video game, converting flat footage into something that felt more tangible, more touchable. As I messed with it, I imagined a near-future in which reporters would use drones to create immersive maps of real-world events, technological landscapes that a reader could wander through - placing themselves in the story, geographically and maybe even emotionally. Maybe it'd save lives, or at least open minds, I thought to myself. Maybe it could keep journalism alive just a little bit longer.

The Year of the Consumer Drone, that heady period straddling 2013 to 2014, fell at the same time that much of the world started to grow skeptical of the big promises that social media companies had spent the last decade making about how the Internet would improve democracy and enlighten humanity. Before graduate school, I'd worked as a reporter in Cambodia, where I focused on how technology was changing politics and society in Southeast Asia at the peak of the techno-optimism era during Egypt's Arab Spring in 2011. Soon after, I heard the first rumblings of the Facebook-enabled genocide in Myanmar (which I've written about before) and began noticing an uptick in threat-filled rhetoric against minorities in Facebook and Twitter posts in Cambodia.

By the time I started graduate school at Stanford, I'd become convinced that the social media danger-signs I'd been seeing in Southeast Asia were not exclusive solely to people who had only just gained Internet access (as was one of the pervasive theories at the time), but were in fact a clear and present threat to the entire world. It was an impression that only solidified as I watched Gamergate mutate into ever more hideous forms on Twitter, and as I watched Republicans and their supporters grow ever more rapidly detached from reality against the deceptively cheerful blue and white backdrop of Facebook.

The initial promise of the Internet, something that I'd been bewitched by ever since I was an extremely online kid in the 90ss and the 2000s, seemed to be rapidly turning into something much more sinister. All of this meant that at the same time I was thinking a lot about drones, I was also thinking a lot about information, and power, and the complex ways in which the two intersected. And, inspired by my new interest in drones, I was also spending a lot of time looking at maps.

In high school, I’d stumbled across Google Sightseeing, a blog devoted to finding and posting pictures of important global locations and interesting features on the then-brand-new and exotically high-tech satellite imagery service. Soon, I was spending hours virtually wandering the planet via Google Earth's interface, searching for ancient ruins, secret North Korean military installations, and buildings that had accidentally, hilariously, been constructed in the shape of dicks. In college and in my first years as a reporter, I'd become interested in the-then nascent concept of citizen and open-source mapping, practices that took advantage of GPS-enabled smartphones and simple browser tools to allow average people to create online maps, of everything from beloved local taco joints to outburst of political violence surrounding elections in Kenya.

And now, I realized, small drones had provided the world with a way to combine these two ideas: high-resolution aerial imagery, and data collected by average people who weren't backed by tons of money and institutional support. While the initial promise of social media had largely turned to ash, this was something, at least, that I could get excited about - another power shake-up that revolved around a physical, tangible object that could collect information, a platform that least offered the user more control than the likes of Facebook or Twitter.

While I was highly aware of the ways that authoritarian states, police, and creeps could use drones for their own nasty ends - much like social media - I'd become convinced that this wasn't a deal-breaker, or was not particularly different from how any other technological artifact, from smartphones to Jeeps, can be used both to help and to harm. After all, in those sci-fi movies in which dystopian governments use drones to control an oppressed population, the screen-writers very rarely accounted for the possibility of the peasants having drones of their own. And while consumer drones could theoretically be banned from sale in stores, it would be essentially impossible to stop someone from building their own drone from well-nigh ubiquitous electronic parts.

If drones meant the break-down of a millennia-old system in which only a rarefied few could make their own maps, or shoot their own pictures from the sky, than that was something I was very interested in indeed. Perhaps the revolution would be televised after all. Just not from the ground.

Whenever I talk about small drones and power, I think of the story of Irendra Radjawali: an Indonesian geographer, drone pilot, and exceptionally fearless indigenous rights activist.

Radja, as he prefers to be called, has the look of the typical sort of gentle nerd that populates global GIS offices everywhere. But as you talk to him, he’ll casually toss out stories of eyebrow-raising exploits as if they’re the sort of thing everybody does, like being jailed for months by Suharto’s regime after participating in the explosive Indonesian pro-democracy protests in the 1990s. I first got to know him when I was doing research for 2015 Slate story on how indigenous people are taking advantage of drone technology, and I've been thinking about his work ever since.

It was during the course of Radja’s PhD research at a German university in geography and mapping that he became acquainted with the Dayak people, an indigenous group who are native to the vast, biologically luxurious, and ever more imperiled Indonesian island of Borneo. The Dayak were (and still are) facing constant incursions upon their traditional lands by miners, loggers, and palm-oil growers, who used their deeper pockets to beat back the legal cases they filed against them.The Dayaks were at a legal disadvantage because they often lacked good, up-to-date maps of the land they owned - and they knew that getting newer maps made would be an arduous and highly expensive process.

It was in this context that Radja, conversant in the geography world’s buzz over how newfangled drone technology might make mapping much easier and cheaper, came up with an idea. He’d work with the Dayaks to teach them how to build and fly drones. And once they had a drone, they could make a map. And once they had a map, they stood a much better chance against the interlopers trying to log and mine on their land in court.

To that end, Radja and his Dayak collaborators began to fiddle with a series of different home-made drone designs, using inexpensive parts from electronic stores and a standard digital camera glued to the drone’s undercarriage. They figured out how to process the drone photographs with open source software on a standard laptop. Eventually, they were ready to turn drone mapping dreams into action. Their home-built drone took flight over the tropical jungle and snapped photographs of scarred-up stands of formerly pristine forest and rivers polluted by ad-hoc illegal mines. They took those photographs to court, and this time, they were able to win, bolstered by the fact that they could now point to evidence of people taking liberties with their territory in a very high quality photograph on an accurate map, which could then be easily compared with other maps. (You can read Radja's resulting academic paper on this work here).

Radja and the Dayaks had thus, early on in the rise of the global consumer drone industry, thrown down a very interesting gauntlet. While the drone imagery was no magic bullet - as I write this today, the Dayaks are still fighting for their land - their new-found access to little flying robots did markedly level the playing field against far more wealthy, powerful interests. And back in 2015, their story highlighted a vital truth to me: thanks to cheap drones, mapmaking and aerial photography was no longer exclusively a tool for the well-heeled. Something new was taking form, ushered in alongside all those store-shelves filled with weird little camera helicopters. A new thing that I've been obsessed with writing about, and with thinking about it, for over a decade.

What happens to the world when almost everyone can view it from a perspective that was formerly reserved exclusively for gods, or the wealthy? That's the central question that keeps me coming obsessively back both to drones themselves, and (most importantly) to the people who use them. It's the core idea behind little flying camera robots that keeps me digging deeper. While drones, like so many other new(ish) technologies haven't changed the world in the exact ways that I, or anyone else, assumed they would ten years ago, they certainly have shaken things up - and they continue to do so, in ways which are both fascinating and disturbing, and sometimes lurking in the middle-ground between the two.

Ukrainians are using drones both to fight Russia, and to collect evidence against it: high-resolution maps, photos, and 3D models of the scenes of Russian war crimes will almost certainly be used to at least some extent in international criminal court. Of course, this goes both ways: Russians are also using drones to fight Ukraine, locking both countries in a long-running, brutal technological cat and mouse game with an ending that remains very difficult to predict.

But while people absolutely do use small drones for war, policing, and other dystopian-type use cases around the planet, the majority of the planet's drone users aren't fighting wars or secretively surveilling political dissenters. Drones that are used to blow things up and to oppress minorities understandably get the headlines, but they also represent just one slice of what the world is actually doing with these weird little buzzing machines.

never trust a dad with a drone

Farmers using infrared sensors to see how thirsty their plants are, ecologists evaluating the nesting patterns of unusual albatrosses, construction workers swapping out the deadly practice of clambering up poles for a digital-eye in the sky. Transportation planners mapping out railways, teachers letting kids in on the strange secrets of electronics, disaster responders counting burned-out trees, and search and rescue pilots trying to find both missing people and missing Golden Retrievers. Highly competitive drone-racers participating in televised matches, and your dad screwing around in the backyard with a drone that he intends to use to take awkward photos at the next family reunion: they too are part of the modern Drone Armada.

Journalists and movie-makers now use drones so constantly to cover events and to shoot staging scenes that their presence has faded into the background - an innovation so widely adopted that many people have already forgotten what it was like when they weren't there, just the same way most of have adapted to the advent of the mobile-phone era. There was a time (dim and sepia-tinted as it is in my memory) when manned helicopters captured every aerial shot you saw in a TV show or in a movie: now, everyone from insolent teen TikTok travel influencers to renowned war correspondents can capture sweeping views of beautiful places and carnage-strewn disaster scenes on a whim. With the coming of drones, our culture has become vastly more saturated with the big picture view. Our minds may not have expanded, but at least our perspective - in the most archaic sense of the word - has.

Lawmakers around the planet have had to scramble to keep up with this deluge of drones, and I have to imagine many are ruing the day when we figured out how to make smartphones that fly. This decade-plus of constant legislative and policy-based chaos has also held my attention on drones, objects whose very physical mobility has forced aging US politicians to actually take action - unlike their continuing regulatory indifference to the invisible horrors that the likes of Facebook have visited on the world, social media companies that produce dangerous products that are unlikely to be sucked into the engines of a passenger jet. In many ways, the political battles and endless dickering around what to do about drones is the leading edge of global tech law, and paying attention to it can, just maybe, give us more clues about what's coming next.

Chief among those gathering storms on the horizon is the US backlash against Chinese drone-makers, a move that proponents claim is a strike against the dual evils of big-business monopolies and shady data-stealing technological processes - a backlash that's closely mirroring the much-more-throughly covered US government effort to ban TikTok. Lawmakers in some states, like Florida, have already banned government employees (which includes university researchers) from using Chinese drones, and federal restrictions on their use may be on the horizon. While there abs0lutely are valid cybersecurity reasons to be concerned about Chinese-made drones, I also worry that this crusade could inadvertently result in the end of that million-flowers-bloom of average people using drones for fascinating things that has held my interest for so long.

The US-based consumer drone makers all gave up the ghost by the late 2010s thanks to a combination of genuine manufacturing challenges and good-old fashioned egregiously dumb screwups, ceding the normal-people drone buyer market to DJI and a few other Chinese companies - a strategic move that we're now, not surprisingly, really coming to regret. The US-based drone makers that remain, some of which have been anointed with official sanction from the US Department of Defense's so-called Blue UAS program, specialize in making extremely expensive drones for police and security specialists, a suite of tactical-looking beasts that are almost all roughly as useful for move-making, mapping, and science as a (flying) baked potato. And the price point really matters. An underpaid freelance reporter or a PHD climate-science researcher can afford a $1200 drone: they are not going to be able to find $30,000 for a drone that doesn't even do what they need it it do between the couch cushions.

All of this means that as I write this in 2024, we're looking at a sudden return to the pre-DJI drone world I remember from 2013, where you had to build your own drone if you wanted to fly one - and good luck with that, if you weren't a life-long model aircraft nerd. Some people may welcome this, excited about a return to an idyllic world where jerks no longer do things like, say, harassing both un-housed people and local bears with a drone then posting the videos on social media (highly illegal activities that the FAA is, bizarrely, taking far too long to actually crack down on).

But this Screw Those Drones take, understandable as it is in the face of the highly visible dickhead with a drone contingent, ignores the power dynamics that accompany these little flying robots, annoying as they are, and the the fact that they do give people - including journalists and activists - the sudden ability to regard the world from a perspective once reserved only for the very deep-pocketed. What happens if that power is taken away, if we return to a world where only police and the military have drones? Do we really want to go back to a society where the powerful can look down on us, and we can't easily look down on them in return? This tech-mediated gaze into the face of power politics is yet another entry in the combination of things that keeps me coming back to these mostly-identified flying objects, human-built devices that have (like all the great artifacts) taken on a life of their own.

I have to end this thing somehow, and I have to sum up why I'm fascinated by drones in a few lines of immense profundity. Which is, as it turns out, really hard. It's like trying to sum up why you prefer your favorite color - but here I am, trying. Yes, it's partially the personalities of the people who use drones, the sea of alternately marvelous and terrifying things people come up with to use them for, the political debates that swirl endlessly around them.

But it's also this: that drones are the realization of an ancient human dream, the fantasy of being able to detach our souls from our bodies and to fly, to soar far above the physical and geographic constraints that usually confine us. They are flying machines that we use not to transport our bodies through the air, but our minds.

I can't get tired of thinking about that.