Why I Care About Drones - Part One

What's the deal with me and drones? How did a journalist get into little flying camera robots? Here's my attempt to explain.

The white object paused for a moment in the late-fall sky over Palo Alto, buzzing in place like an electric white hummingbird. Then, as I watched, it floated with eerie, perfect stability in the direction of the Stanford soccer fields, red and green lights blinking UFO-style on its undercarriage. I’d never seen anything man made, move like that before, flying in stable, parallel lines like a freakishly disciplined hummingbird.

I couldn’t take my eyes off it.

For a long time, I’d been cynical about the world-shaking wonders that techbro-engendered innovation would supposedly bestow upon humanity. I’d spent the last few years working as a reporter in Southeast Asia, and I’d watched in real time as Facebook came to Myanmar and was, almost immediately, turned into a tool for broadcasting genocidal hatred against religious minorities. (I've written about that here).

I’d also watched social media companies decimate the journalism industry I had once, all too foolishly, dreamed of making a career in. Since starting a master’s degree program at Stanford a few months earlier, I’d seen nothing to convince me that my grim take on the state of modern technology was wrong.

And now I was looking at something that actually surprised me, a little flying robot hovering calmly way up above Silicon Valley’s 2013-era wasteland of cat-washing startups, gig-economy scams, and Facebook-fueled privacy violations.

It wasn’t like I was totally unaware of drones, or the fact that regular people could buy them now: I’d read about them in the normal course of keeping up with tech news, and one of my college friends had even made drones the focus of his own career in journalism. But coming face to face with one, away from all the abstract talk about them on Twitter? That was different.

I started to follow the drone across the playing fields, the first one I’d ever seen.

I wanted to see where it was going to land.

That moment is my drone origin story. It’s the moment where I was formally introduced to the weird helicopter-computer things - specifically, the kind that are relatively cheap, sold at normal stores, and intended for civilian use - that I’ve spent the last decade building my career around.

Which leads to a second question for anyone who knows me and what I do: why have I stuck with drones for so long, anyway? What’s gripped me so hard - someone who began my career as a journalist with zero engineering background to speak of - about little flying camera robots?

On one level, my career in drones has been a matter of practicality, a pragmatic move in an uncertain world. I was following a familiar narrative: a disillusioned millennial realizes that the foreign correspondent career they’d dreamed of has been buried alive in a shallow, unmarked grave by the likes of big-tech social media companies and ever-more voracious executives , and that the time has come to move on to better-compensated, STEM-filled pastures.

But of course, it’s more than that.

I’ve spent a decade working with, writing about, and thinking about small drones because something about them resonates deeply with the lizard-level part of my mind responsible for finding things cool as hell. And it’s not just that civilian drones are intrinsically cool, which even the most avowed drone-haters will probably admit when pressed: they’re cool in an intensely complex and fraught way, man-made tools equally capable of freaking people out and fascinating them.

Drones bring out strong reactions in people, in a way that many other modern tech wonders, from food-delivery apps to high-resolution TVs, simply don’t. They’re shape-shifters, chameleons, objects that can be used for everything from pure altruism to hideous violence - and while these transistive properties aren’t unique to drones, it’s also true that your iPhone can’t physically roam. Which, of course, a drone can (albeit much less independently then many people believe is possible).

Among other things, drones are:

Mass-produced flying cameras that even poorly coordinated people (like me) can pilot, meaning that for the first time in history, anyone with a few hundred bucks and functional thumbs can gaze, god-like, upon the vast expanse of the earth from above.

Easily-accessible mechanisms by which cops and oppressive governments can create a to-go version of the panopticon, hovering eerily above a civil rights protest near you.

Near-miraculous map making devices that humanitarian aid workers can use to rebuild cities and lives after nightmarish natural disasters, and that indigenous activists in Borneo can pilot to capture data good enough to win them court cases against gigantic, land-grabbing corporations.

Off-the-shelf products that Ukrainian soldiers use to super-accurately target artillery strikes against Russian armor, and to blast Soviet-era grenades directly into the faces of enemy fighters, whose last, surprised, moments are captured on grainy drone-borne live video. (I’ve written about this quite a bit too).

Flying eyes that have, in just a decade or so, captured an entire world of perspectives that no one had ever seen before - drone’s-eye views that we now see everywhere in art, film, and on television, aerial angles we’ve grown so accustomed to seeing that it’s easy to forget they weren’t always there.

That’s a lot of complexity to consider when we’re talking about a four-armed, plastic-paneled, model helicopter that kind of looks like a bug.

As for me personally, it’s all of these things, but there’s one more factor. The biggest one of them all.

I’m fascinated by drones because I am not, on the face of it, the kind of person anyone would have expected to work with them for a living.

In large part, I owe my career in drones to spite.

While I’ve always been enthralled by science and technology, I’m cursed with a form of dyscalculia which makes me impressively bad at arithmetic. I’m one of those poor saps who still can’t calculate tip percentages in my head without whipping out my phone, or without making a joke about how it’s a good thing we actually do all have calculators in our pocket nowadays, ha ha ha. (I’m really, really glad that teachers today have lost the ability to make that comment).

As a nerdy kid, I desperately wanted to be good at math. I believed the scientists who said that grasping it was the key to perceiving larger worlds of wonder and cosmic understanding (and so on), and I also knew that decent standardized math scores were a necessary prerequisite for getting into good colleges in the throat-slittingly brutal environment of 2000s undergrad admissions. But no matter how hard I tried, my SAT math scores never rose above the level of “dismal,” a failure that looked even more weird and embarrassing when compared to my perfect scores on every verbal-based standardized test I ever took.

I suffered, in other words, from a terrible case of lop-sided brain.

Eventually, my world-class inability to calculate tips in my head festered into a deep well of resentment towards the entire system, which, appeared to be designed to make damn sure that everything in life - from college to career to basic economic stability - rode upon if you could do a quadratic equation in a painfully fluorescent-lit room without looking at your notes or not.

When I graduated right into the teeth of the recession in 2010 and started my first job as a reporter, in an industry that I was well-aware was dying all around me, and in an era where everyone in power devoted a lot of time to waxing poetic about the noble virtues of boy-genius STEM professionals in hoodies, my ressentiment grew even more intense.

I spent a lot of time worrying about what would happen if I could never find another journalism job, if I was doomed to eventually end up in the garbage-bin of precarious employment that our culture had, in its infinite wisdom, designated for losers (like me) who had debased themselves by getting an English degree.

Such was the anxious, fear and loathing-filled head space I was in at the start of my journalism master’s degree at Stanford in 2013.

While I wasn’t deluded enough to think that a journalism master’s degree would magically usher me into a well-compensated and rewarding career as a foreign correspondent in the media hellscape of the 2010s, I’d decided to enroll in the program on the basis of two things.

First: having any kind of Stanford degree at all might help keep my resume from being immediately filtered out of an employer’s inbox by the cruel hand of a sorting algorithm, and that was worth something.

Second: maybe, while spending a year hanging around Stanford in the midst of all that irrational, sun-kissed, economic exuberance, I’d find something to do that wasn’t journalism. Something where I might actually get a reasonable amount of money. Something I liked doing in a place that would be willing to overlook my shameful failures in the realm of 6th-grade fractions.

But I wasn’t very hopeful.

All of these bleak and confused visions of my future were on my mind on that day at Stanford in 2013, and maybe that’s also why I started following the drone. Eventually, I zeroed in on where the DJI Phantom had come from. I was not very surprised to find that it belonged to two friendly, tanned Stanford seniors in flip-flops. Everyone at Stanford was friendly, tanned, and had on flip-flops.

Like most everyone else I’d met since I’d arrived here, they told me they were working on a start-up idea. Specifically, they’d use drones to deliver burritos. While I was not very interested in a prospective future where bubbly future venture capitalists had legal carte-blanche to drop foil-wrapped carne asada projectiles onto my head, I was very much interested in the drone itself. And they were eager to tell me about it.

It was a Phantom produced by China’s DJI company, it cost around $800, and it was, I’d later learn, the first truly beginner-friendly drone capable of shooting truly high quality video to hit the market. You just had to attach a GoPro sports camera to the bottom, and although the Phantom had only been released in January, YouTube was already filling up with sweet aerial surfing videos.

As I rode my bicycle back to my apartment, I thought about the drone. I could think of a lot of things that reporters, like me, could do with it.

Report on war zones from a safer distance away from the fighting and the violence. Investigate distant, closed-off places where reporters would usually be denied access, both by natural forces and by people who’d rather not be investigated. Capture striking and never-before seen angles on natural disasters, destruction, and large-scale human dramas, from refugee camps to anti-government protests.

Anyway, I needed to write a story about something for my journalism classes - and digging into drones sounded more exciting than anything else I could think to write about, in the unrelentingly sterile environs of Palo Alto.

That’s how, a week later, I ended up at the Stanford UAV Club meeting, which was shortened to SUAVE, an ironic adjective for a group of people who had extraordinarily strong opinions on toy helicopters.

It was emphatically not called the drone club in official communications, and there was a reason for that. “UAV” means “unmanned aerial vehicle,” a technical term that specifically, precisely describes flying, computerized gizmos without people riding them.

Back in 2013, UAV enthusiasts were fighting an increasingly desperate rear-guard action to convince the public to start using that unfortunate acronym to refer to the small, largely home-built hobby aircraft they worked on - instead of using “drone,” an ominous, deadly-sounding word most still associated with the huge, missile-equipped Predators the US government was flying over the Middle East in the course of the War on Terror.

The Stanford UAV Club’s members were almost all aeronautical engineering students, who were, impressively, even more clean-cut and earnest than the other Stanford students I’d met, with a little bit more social awkwardness and a little bit less of that lingering whiff of pure avarice that lingered unpleasantly in the air wherever computer science and business majors congregated (which was pretty much everywhere) .

Most of them, I’d eventually come to learn, were once the kind of kid who’d hang out at airports and memorize the name of every single aircraft they saw fly overhead, who eventually turned into the kind of adult who liked spending their leisure time fiddling with remote controlled aircraft - a pursuit that was both a life-long hobby and also, conveniently, pretty central to their actual academic work.

That was the purpose for the Stanford UAV club: a location, as well as some club funding, for figuring out how to build fun-sized flying machines with computer enhancement, in the fine do-it-yourself tradition that RC hobbyists had been carrying on since the 1940s.

When I walked into that first meeting, after having introduced myself to the club’s president as a journalist, I assumed I’d just be hanging around in a sort of detached, observational role, making my little anthropological notes on the intriguing social customs of Drone Guys (and, perhaps unsurprisingly, they were indeed all guys at the time). Which means that I was a little surprised when, during that first meeting, President Timothy turned to me and the other new guy - a slightly jittery-looking computer science student - and asked if we wanted to get some drone building experience ourselves.

The computer science guy and I flicked glances at each other from across the conference table. Us? We weren’t engineers-engineers, and I’m pretty sure we both had only a very vague, impressionistic idea of what a drone’s guts actually looked like. I assumed that building a drone from scratch involved delicately wiring up precision-electronics in a clean room filled with people in jumpsuits.

Meanwhile, I was so poorly coordinated that I regularly struggled with things like “opening doors with standard house keys.” Were these supposedly clean-cut aeronautical engineering types trying to coerce me into starting a fire so they could collect insurance money?

“It’s easier than it sounds,” said Timothy, in the winsome, boyish voice of a former Eagle Scout.

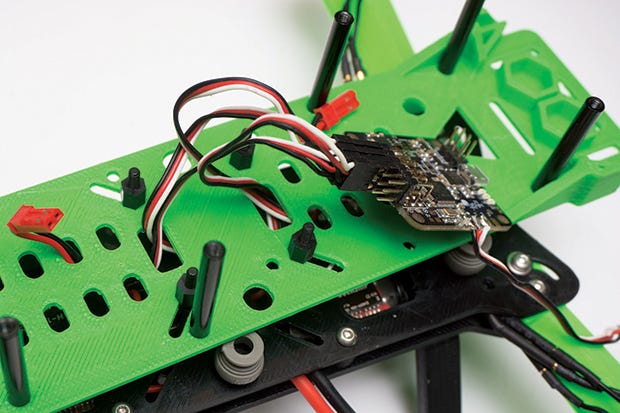

The craft room where SUAVE built its little flying robots was a small, closet-like space: the white foam skeletons of dead model aircraft hung on pegs on the wall, and every spot of available space was covered in bins of unidentifiable wires, tubes, and motors. The club members rummaged around and brought out box after box of electronic bits and batteries, which looked, to my eyes, exactly like the parts one would use to make a low-rent pipe bomb.

“I’ll show you how to get started,” Timothy said, walking over to our table with a laptop with a PDF instruction manual pulled on the screen, and yet another box that contained a selection of what appeared to be dismembered drone arms and bodies, made of metal and red-and-white plastic. “First, we’re gonna need the glue gun.”

“A glue gun?” I said, incredulous.

“Oh, yeah. We do a ton of this drone building stuff with a glue gun,” he replied, serenely.

The computer science student and I exchanged glances again. Wait, this is how they do it? I thought, as I watched the club leader moosh a little tiny brushless motor onto one metallic drone arm with a big, sloppy dollop of hot glue.

This is that engineering mystique, that pursuit of precision brilliance that I’d been led to believe, for all this time, was far beyond the grasp of my feeble, creative-writing-doing brain? They’re literally just gluing shit together?

“Well, that’s all we’ve got to do to attach the motors. Now we’ve got to secure the battery,” Timothy said. And then he reached for the duct tape.

In this way, I came to my second drone epiphany. Yes, it was indisputably true that I was horrible at basic arithmetic, and it was also true that I had only the faintest idea (at the time) how all this electronic junk somehow could be mashed together to produce a flying computer.

But if the bulk of the work required to put together a marvelous little flying robot could be executed with a glue gun and a roll of duct tape you could buy at the drug store, maybe drones weren’t beyond my understanding. Maybe, just maybe, I could learn to build them and fly them myself. It wasn’t like I had anything to lose.

And that’s exactly what I did.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Part Two coming soon, in which I elaborate further about why civilian drones matter and why it’s a good thing, actually, that average people can use them to contemplate the earth from above, make maps, and even the playing field a bit with the powerful.